Money No Enough, Passion Needed Too: Restoring Classic Singaporean Films

Money No Enough, Forever Fever and The Teenage Textbook Movie kickstarted a new era in Singaporean cinema, making them prime candidates for restoration.

By Chew Tee Pao

Film restoration is often thought of as a process that is necessary for older films, perhaps like those produced in the 1950s and 1960s by Cathay-Keris Films and the Shaw Brothers’ Malay Film Productions. When films such as Patah Hati (1952) and Seniman Bujang Lapok (1961) were made, they were regarded simply as commercial entertainment and little effort was made to store them well. Today, they are considered classics and much time and effort has been spent to restore these prints and preserve them for posterity.

However, even films of a more recent vintage are candidates for restoration. Often, a movie is seen as a commercial enterprise, made with an eye towards ensuring relatively quick returns for investors. It is only with the passage of time that some of these movies become classics and end up as candidates for restoration.

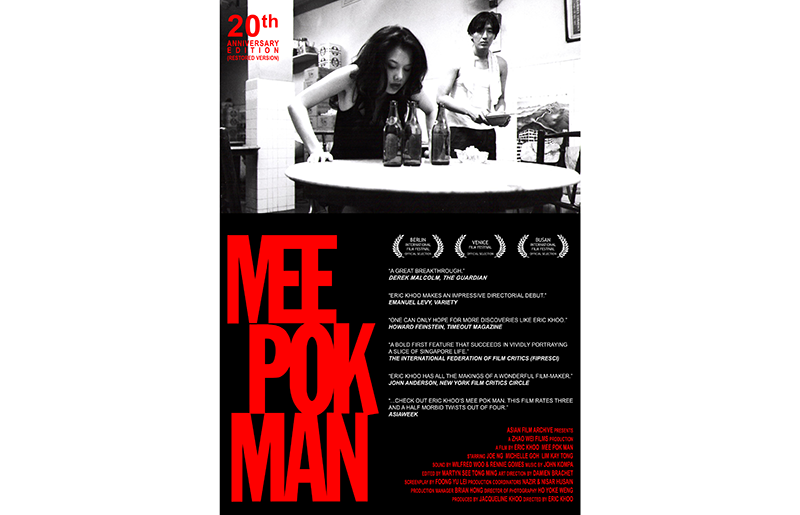

Mee Pok Man

When it first hit local screens in 1995, few people probably recognised the importance of Mee Pok Man, the seminal debut feature of Singaporean director Eric Khoo. The film stars Joe Ng who runs a fishball noodle stall, and Michelle Goh, who plays Bunny, a prostitute. Among the many notable things about the film are its scenes of necrophilia. Significantly, Mee Pok Man helped local filmmakers believe that it was possible to make movies.

In 2015, the Asian Film Archive (AFA), with support from the Singapore Film Commission, carried out the restoration of Mee Pok Man. As the film elements were originally processed in a laboratory in Australia, the camera and sound negatives were kept there. These were subsequently brought back to Singapore, and Mee Pok Man became AFA’s first restored local film from the 1990s revival era.

The restored work was screened at the 26th Singapore International Film Festival in 2015, during the film’s 20th anniversary, in the presence of many cast and crew members. The restoration of Mee Pok Man became the catalyst for the AFA to search for the film elements of other Singaporean works made in the 1990s.

The Iconic 90s Trio

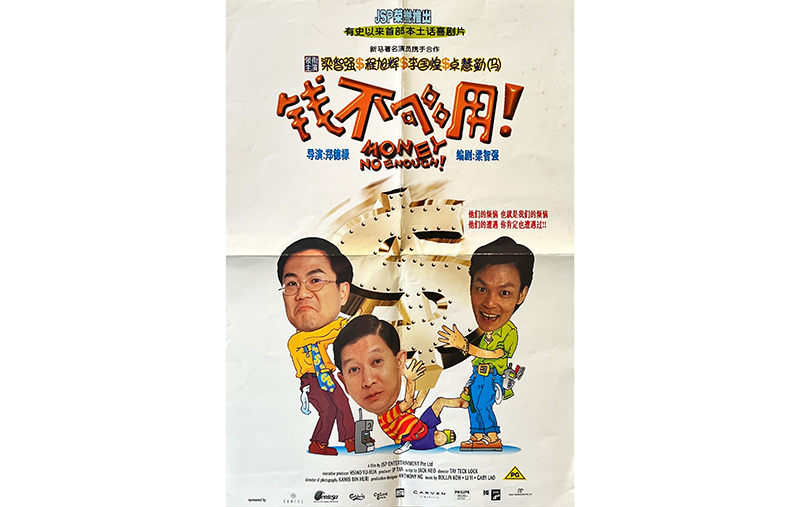

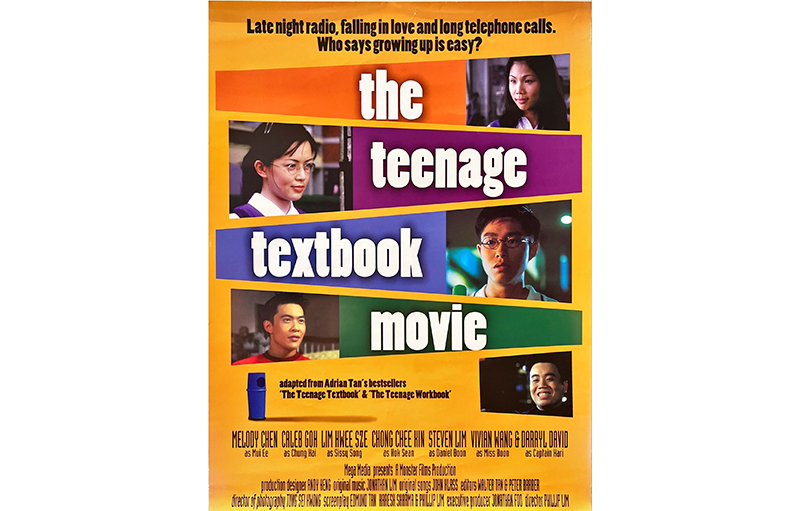

In 2017, the AFA embarked on the hunt for surviving film elements of three other iconic Singaporean films – Money No Enough (Tay Teck Lock, 1998), Forever Fever (Glen Goei, 1998) and The Teenage Textbook Movie (Phillip Lim, 1998) – that were released in local theatres in 1998. These films were instrumental to the revival of Singapore cinema in the late 1990s.

Written by comedian and film director Jack Neo, Money No Enough is about three friends with financial problems who start a car polishing business together. In Mandarin, English and Hokkien, it was the all-time highest-grossing Singaporean film for more than a decade until the record was broken by Neo’s own directorial work, Ah Boys to Men, in 2012.1

Forever Fever is significant because it was the first Singaporean film to be bought for worldwide commercial release by film distributor Miramax. The musical comedy stars Adrian Pang as supermarket employee Ah Hock, who becomes interested in disco after he watches Saturday Night Fever (the 1977 film starring John Travolta). He enters a dance contest to raise money for a new motorbike. Forever Fever is notable for featuring iconic tunes by international group the Bee Gees, and American band KC and the Sunshine Band, which were performed by local artistes like John Klass and Najip Ali.

Meanwhile, The Teenage Textbook Movie is a lighthearted look at the lives and loves of a group of students from the fictitious Paya Lebar Junior College in Singapore. It was adapted from The Teenage Textbook and its sequel, The Teenage Workbook, two bestselling local books by Singaporean lawyer Adrian Tan. The movie topped the Singapore box office for weeks and was the first English-language local film to feature an all-Singaporean written soundtrack.

The AFA already had the 35 mm exhibition prints of these films in its collection and the intention was to restore the films using the original negatives. The original negative is of great value since it is the earliest generation of the finished film and contains the image in the highest quality. The challenge was that many local films that used 35 mm film stock and were theatrically screened in the 1990s had their negatives processed and printed in overseas film laboratories in Australia, India or Thailand. Filmmakers and production companies neglected to retrieve these negatives from the laboratories; over time, the original negatives and prints were either discarded or lost.

Despite being merely 25 years old, the picture and sound negatives of Money No Enough could no longer be found, and the restoration had to be carried out using two 35 mm release prints from the AFA’s collection. Both sets of prints that were donated to the AFA in 2008 were affected by physical wear such as scratches and torn frames, and had contaminants like dirt and dust. The restorer inspected both prints and utilised the copy that was in a relatively better condition for the digitisation. Some 215 hours were spent on digital restoration that included scratch removal, image stabilising, deflickering and colour correction.

With Forever Fever, the issues were different. The film laboratory that had processed the film had been bought over and all the original film, video and audio elements of the film were stored in multiple locations around Australia. The verification, consolidation and coordination of sending all these materials to Singapore took more than a year. The original film negatives exhibited physical wear and contained emulsion defects, glue marks and light scratches, but were overall in reasonably fair condition as they had been kept in a proper storage facility. More than 200 hours were spent on digital restoration, including stabilisation and de-warping.

The film that presented the biggest challenge was The Teenage Textbook Movie. The film negatives had been stored in less-than-ideal conditions. As a result, they accumulated a considerable amount of moisture, and the emulsion of every reel was stuck to the next wound base, creating stains and marks. Broken perforations and scratches were exhibited throughout the print, which had to be repaired before the scanning process. Of the three, The Teenage Textbook Movie took the longest to restore: over 1,000 hours were spent on digital restoration, including scratch removal, stabilising, deflickering and colour correction.

All three films – Money No Enough, Forever Fever and The Teenage Textbook Movie – were restored in tandem by different film restoration laboratories. After months of hard work, the films were presented in November 2018 at the Cathay Cineplex in partnership, and with support from, the Singapore Film Commission at “Singapore Classics Reignited”, as part of the Singapore Media Festival.2 The films were screened in their intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1 through digital cinematic projection for the first time, 20 years after their releases in 1998.

The restoration process allows audiences today to experience the films as they were first shown. But there are other benefits as well. Jack Neo told the Straits Times in 2018 that he was moved to tears while watching the restored version of Money No Enough. “Some of my good friends who were featured in the movie have since passed on,” he said. “But I also cried because it brought back so many memories. Just look at all those huge mobile phones that we used in the movie – I would call this a period film.”3

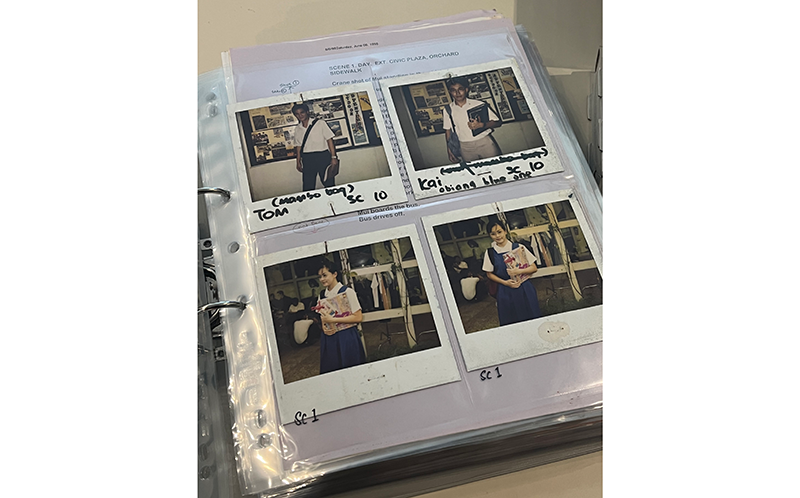

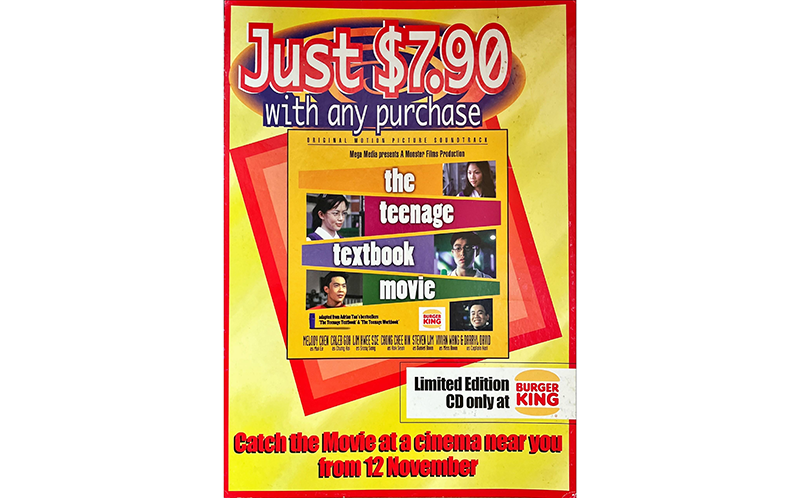

Sometimes, in the midst of getting the different film elements together, other treasures are uncovered as well. While restoring The Teenage Textbook Movie, the AFA came across a collection of paraphernalia and production-related materials that provided insights into the making of the film. This included the Nokia 5110 advertisement that featured the stars of the film posing snazzily. There was also a limited-edition original movie soundtrack on CD, which fans at the time could buy for just $7.90 with any purchase at Burger King.

The Forgotten Femme Fatale

These films from the 1990s are vital milestones in Singapore’s filmmaking history as they represent a new era in moviemaking here after the Shaw Brothers’ Malay Film Productions and Cathay-Keris Films ceased operations in the late 1960s and early 1970s respectively. For close to 30 years, the local film industry had been largely dormant until Mee Pok Man showed the way forward.

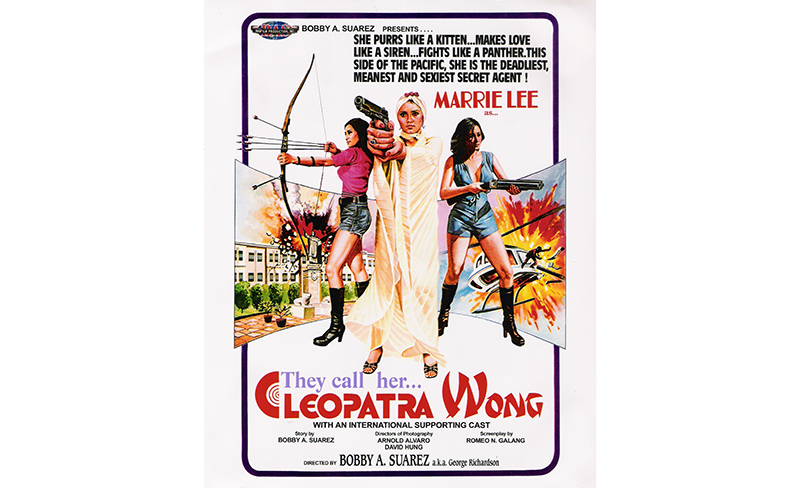

The industry did display minor flickers of life in the decades between these two eras though. There was at least one important film that was partly made in Singapore: a 91-minute movie by BAS Film Productions in 1978 titled They Call Her… Cleopatra Wong.

Inspired by the films of Bruce Lee, They Call Her… Cleopatra Wong incorporated elements from both Western spy and Asian martial arts genres. The film was directed by the late Bobby A. Suarez (1942–2010), a Filipino filmmaker who went by the pseudonym George Richardson. It was a multinational production involving producers from Hong Kong, Singapore and the Philippines.

The film stars a then 18-year-old Singaporean, Doris Young – who went by the stage name Marrie Lee – in the titular role as a sexy Interpol secret agent, who did many of her own stunts.4 (Marrie Lee was created to capitalise on the fame of the late Bruce Lee; some people even thought she was Bruce Lee’s younger sister.5) Dubbed a “female James Bond” by the Asian press, Cleopatra Wong teams up with her Filipino counterpart to bust a counterfeit currency syndicate.6

In a 2003 Straits Times interview with Quentin Tarantino, the Oscar-winning Hollywood filmmaker revealed that the film had been a major influence for him, especially for the Kill Bill series (2003–04). “One of the movies that was made in Singapore in the 1970s that I loved was Cleopatra Wong. Cleopatra Wong was a gigantic inspiration,” said Tarantino. He loved the movie so much that he got a friend to paint for him a huge canvas of Wong in her nun outfit and toting a quadruple-barrelled shotgun; the painting graced the foyer of his living room. “So as you walk through the door, you’re facing a gun barrel by Cleopatra Wong,” he said. “There was even one time when I was writing Kill Bill that I was thinking of putting a character in a nun’s outfit.”7

In 2008, the AFA planned to collect and preserve the film’s materials but were told by the filmmaker and Young herself that the original film negatives and prints of the film had been discarded as they had deteriorated and had become unsalvageable. Only video copies of the film on digital betacam tapes survived.

In 2017, the AFA decided to see if other prints could be found. The film had travelled extensively to parts of the Middle East, Europe and North America as evidenced by variations of the film’s promotional posters in different languages. Knowing this, the AFA put out a call to members of the International Federation of Film Archives around the globe in search of surviving film elements.

The call uncovered the existence of several prints residing in the film archives of Austria, Denmark, Italy and Switzerland. In consultation with the organisations caring for these materials, the AFA decided to digitise a 16 mm print with burnt-in Danish subtitles with the original English soundtrack loaned from the Danish Film Institute, and a German-dubbed 35 mm release print loaned from Filmarchiv Austria.

The restoration was laborious as the colour for both sets of prints had faded greatly and were also affected by shrinkage and heavy scratches. But the greatest challenge was discovered when the prints were compared with the existing video copy of the film. The AFA realised that there were frames missing from the 35 mm print that it had planned to use. Fortunately, the 16 mm print came in handy for recreating the missing frames and shots.

The restoration of They Call Her… Cleopatra Wong took two years and was completed in 2019. However, due to the Covid-19 restrictions for theatres in Singapore, the AFA was only able to present the restored work in September 2021.8 It was finally screened at the Oldham Theatre in the National Archives of Singapore, with Doris Young in attendance. (There was also a second run in July 2022.9) The multiple runs saw sold-out screenings and a renewed interest in the actress and the character she played.

They Call Her…Cleopatra Wong serves as an interesting restoration case study for the AFA in how variants of the same film obtained from different sources can be pieced together to culminate in a meaningful result. It is also interesting to look at why these variants existed, and why the film was edited and distributed differently. These could be for a combination of reasons – like the accidental loss of frames from re-splicing and re-editing the film to suit a specific market or, possibly, censorship.

The process of recovering original film elements of supposedly lost or forgotten works is a long-drawn out one and frequently involves serendipity. And this would not be possible without the persevering work of film archives around the world.

Chew Tee Pao is an archivist with the Asian Film Archive. Since

2014, he has overseen the restoration of more than 30 films from

the archive’s collection.

Chew Tee Pao is an archivist with the Asian Film Archive. Since

2014, he has overseen the restoration of more than 30 films from

the archive’s collection.NOTES

-

Yip Wai Yee, “Mass-Appeal Movie-maker,” Straits Times, 20 December 2012, 4–5. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Singapore Classics Reignited,” Asian Film Archive, accessed 26 January 2023, https://www.asianfilmarchive.org/event-calendar/singapore-classics-reignited/. ↩

-

Yip Wai Yee, “Money No Enough, 20 Years On: The Singapore Movie That Made History,” Straits Times, 7 November 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/lifestyle/entertainment/money-no-enough-brought-the-entire-singapore-film-industry-to-a-whole-new. ↩

-

“Biography,” Cleopatra Wong, last accessed 25 January 2023, http://www.cleopatrawong.com/Biography.htm. ↩

-

Geoffrey Eu, “Smash! Bang! Pow!,” Business Times, 1 July 2005, 30. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Sandi Tan, “Cleopatra’s Back in Action,” Straits Times, 9 March 1997, 5. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Ong Sor Fern, “Tarantino Thrills First Blood,” Straits Times, 22 October 2003, 2. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Restored: They Call Her… Cleopatra Wong (1978),” Asian Film Archive, accessed 18 March 2023, https://asianfilmarchive.org/event-calendar/restored-they-call-her-cleopatra-wong-1978/. ↩

-

“They Call Her… Cleopatra Wong (1978),” Asian Film Archive, accessed 18 March 2023, https://www.asianfilmarchive.org/event-calendar/they-call-her-cleopatra-wong-1978-2022-3/. ↩