Tok Sumang: A Translation

An English translation of the short book, Tok Sumang, originally written by Malay literary pioneer Muhammad Ariff Ahmad.

Translated by Ahmad Ubaidillah

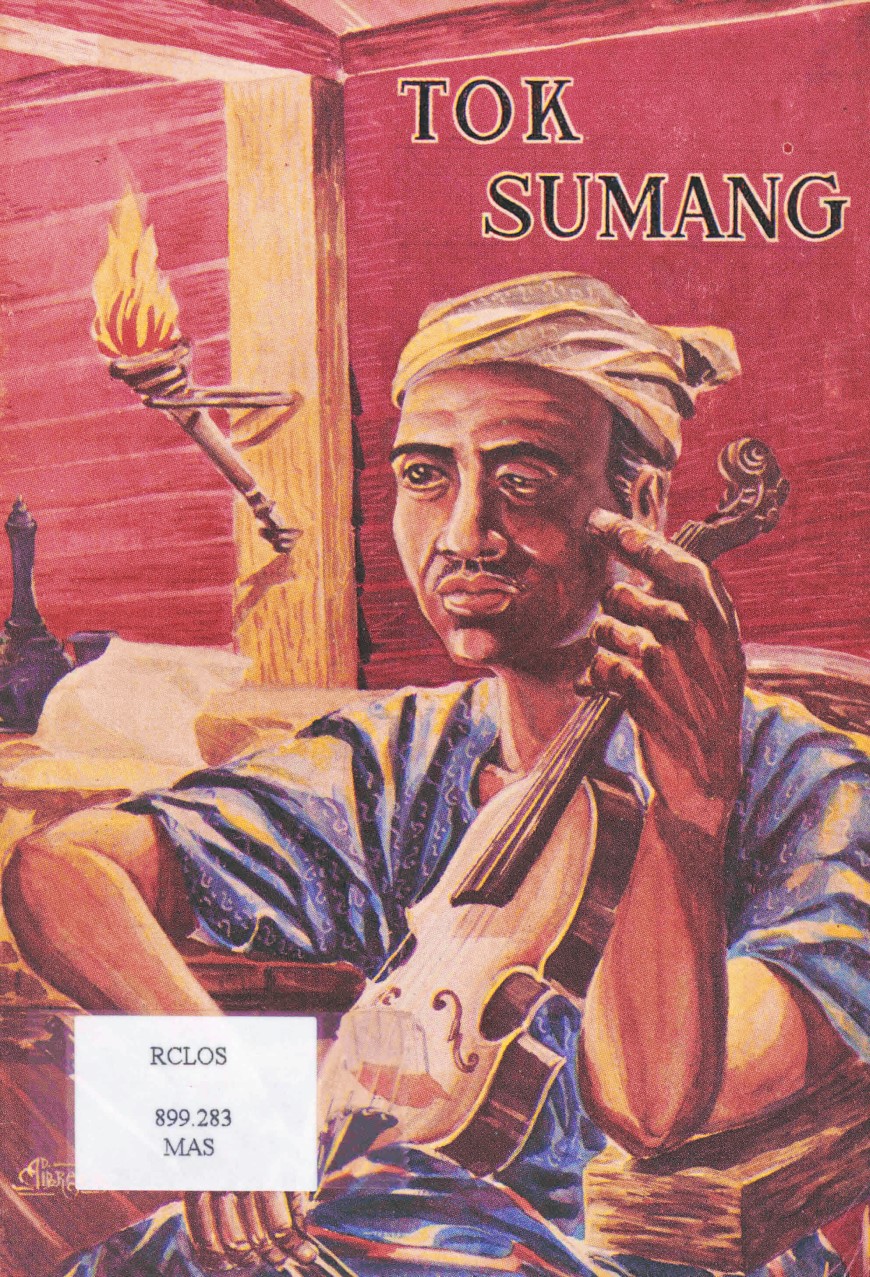

The book titled Tok Sumang was written by the Malay literary pioneer Muhammad Ariff Ahmad (under the pen name Mastomo). Published by Geliga Limited in 1957, the work details the life of Wak Sumang, starting from his time as an official in the court of Lingga Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar Shah (r. 1841–57) to his journey to Singapore where he founded a kampong in Punggol. Muhammad Ariff based the book on stories he had heard while he was teaching at Sekolah Melayu Ponggol (Ponggol Malay School).

The book was translated into English by Ahmad Ubaidillah, who is himself a descendant of Wak Sumang. Ubaidillah also wrote the following introduction.

My fate was intertwined with Punggol long before I was born. When I was a young boy, no older than nine or ten, my maternal relatives would often have picnics and gatherings on Punggol Beach. This was before development works there, so all that the beach had was white sand peppered with boulders, and the long crusty jetty that jutted out into the sea. The adults would sit by the shore under the swaying branches of trees, while my cousins and I swam and raced along the beach, building sandcastles and digging holes in the sand just for the fun of it.

As a young boy, these outings were significant for many reasons. They formed the core memories of my childhood. Even today, I still remember the impressions that Punggol Beach left upon me in my formative years: the blistering heat that made my skin prickle, the lulling sea breeze and its salty scent, and the sunburns when we did not apply enough sunblock. I also vividly remember my grandmother perched by the old jetty holding onto a small circular fishing rod, her hands deftly twirling the string whenever she felt a tug.

It was there on Punggol Beach that I experienced kinship with my cousins while playing on the beach. I recall how we would dig holes by the beach, saying that this would be where our parents could wash their hands after eating. In the sea, we would divide ourselves into pairs and sit on each other’s shoulders, tussling in a battle to see who would be able to keep their balance.

One day, I realised that none of my school friends ever went to Punggol Beach for picnics. Even my friends who lived in Sengkang, Hougang and Punggol would rather make a trip to beaches with better amenities, such as East Coast Parkway or Changi Beach. It later dawned on me that my family’s decision to picnic on Punggol Beach wasn’t due to the geographical factor, but a sentimental one.

After all, Kampong Punggol (Kampong Wak Sumang) was where the maternal side of my family – grandparents, mother, uncles and aunts – had grown up. My grandfather, Ismail Awang, was a fisherman who would sail out to sea in search of a catch to bring back ashore. After the village was demolished in the 1980s, he worked for Outward Bound Singapore, ferrying people to and from Pulau Ubin. I remember being on his boat buffeted by the waves, sitting behind him as he stood tall over the boat’s rudder. A special treat was him taking us – his grandchildren – to the deserted side of Pulau Ubin to look for things to use as bait. The shore would be exposed during the receding tide, and I remember walking on the soft slimy sand, squirming at the strange sensation.

My mother’s siblings were raised in Kampong Punggol and lived there until their thirties. My mother, the youngest, lived in the village until she was 14, before the government provided the family a flat in Hougang. She attended the now-defunct Aroozoo Primary School in the vicinity of Punggol, where she would pass by the pig farms of Jalan Kayu.

In the 2000s, Punggol Beach was all that was left of their idyllic kampong life: a memento from a different period in time. Whenever we drive to the beach today, we would pass through a winding road and my mother would point out where her house had been. But from the car, all we can see are trees.

Thus, Kampong Punggol has always been an invisible yet palpable entity to me: often present in conversations, like an elder in the family who has long passed away. Being born in the 1990s, long after the village had been demolished and the villagers relocated to high-rise flats, all I know of the kampong were from the stories told by my parents and elders. They talked how they were able to eat fresh seafood, the sight of the beautiful beach, the close proximity of their homes to the sea, the laidback kampong lifestyle and how it compared with their current lives. These stories, unknowingly, created a bond between me and Punggol.

It was my mother who told me that we are the descendants of Wak Sumang, the founder of the village who hailed from Riau. My grandfather was the cousin of the last headman of Punggol, and he received a hefty compensation when the villagers were asked to leave. Unfortunately, as is the norm in many Malay families, we do not document or record our genealogy. Whatever information we receive about our ancestors and lineage are passed orally from generation to generation.

I feel an attachment to the historical figure of Wak Sumang, and this personal link bears some significance for my decision to take up the task of translating Tok Sumang (tok is a nickname for grandfather or grandmother) into English. This is a story about Wak Sumang by the literary pioneer Muhammad Ariff Ahmad. But like other Singapore pioneers such as Munshi Abdullah, Naraina Pillai and Tan Tock Seng, Wak Sumang is not affiliated to any ethnic group. In the context of our nation state, we are of one community and society. We are tied and bound by one common history that is filled with colourful historical figures. It is our privilege to have such individuals who belong to different cultures.

Published in Malay in 1957, Tok Sumang remains today an important work in local literature. It contains numerous elements that are relevant to and benefit a modern reader – from the wise and colourful proverbs to the historical lessons gleaned from the feudal period of the Malays. The work is unique as it connects a Malay historical figure to an existing and thriving location in Singapore: Punggol, where there is now an LRT station and various roads named after Wak Sumang.

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad wrote this work in a clean and precise prose that is easily understood and enjoyed by a contemporary reader. The pace is fast, the paragraphs brief and the lessons aplenty. It is a simple yet compelling read that can be completed in just a day or perhaps a few days. It is my hope that the Malay version will be republished, so that today’s generation will be able to read it.

I hope that the translation of this historical work will add discursive value to existing local Malay literature. But for it to do so, one should first assume a critical and creative lens when understanding historical texts.

The key questions we should ask ourselves are: How do we appreciate the historical value of a work while also applying it to the current context? How do we find relevance in a historical work that would add value to current discourse? How do we ensure that works such as this remain beneficial to society?

The answers to such questions lie in our ability and willingness to internalise the spirit and essence of a text, and not only its outward form. If we just study the text at the surface level, we will be limited in the value that we can derive from it. For example, we would only see Tok Sumang as a work of historical fiction about a personality from the Malay feudal past.

To me, Tok Sumang can be used as a medium to appreciate the history and traditions of Malay culture and, at the same time, transmit the values and ethos of the culture. Celebrations, decorations and attire are but superficial markers of one’s identity. Though important, what substantially defines an identity lies in the values and principles of a culture, which in turn have been shaped by history, events and people.

Through Tok Sumang, we find a connection to the wider Nusantara region that is often forgotten today. We are reminded of the feudal links in Malay history, whose remnants can still be found in our local context.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from Tok Sumang is its inherent storytelling nature. In a world that is increasingly finding value in data and statistics, we must not lose sight of the value of tales and stories. Although we are unable to verify the historicity of this work, this is the unique value of historical fiction: It allows the creative spirit to roam in a spacious field bordered by facts and reality.

Therefore, a critical and creative lens is needed when consuming any text, including Tok Sumang. I am hopeful that through this work, readers will be able to tease out more value and meaning that are unique to them and that would enrich their lives.

The National Library Board has digitised the original book, which can be accessed here.

Ahmad Ubaidillah

April 2023

Foreword

Shahrin and Shaharzat,

My children,

I first developed the story of Tok Sumang when I was assigned to teach at Punggol [Malay School] on 7 January 1957. The information was gathered from the people who acknowledged Tok Sumang as the founder of Kampong Punggol.

The two of you did not know anything because you were too young: Arir was 2 years and 3 months old, while Arah was merely 1 year and 4 months. For this reason, I published this book for your friends who are now able to read, so they would know that Kampong Punggol was established by the Malays.

When the two of you are able to read, do read [the book] and explore the great tales of past Malays that are long forgotten due to the state of our community now – outwardly calm, but inwardly tumultuous.

Hopefully, this effort will not be in vain.

Mastomo (Muhammad Ariff Ahmad)

Singapore, 14 July 1957

War

In the year 1867, almost a hundred years ago, a tragic internal war broke out in Pahang. Wan Ahmad attacked his brother, Wan Mutahir, who had become the ruler, replacing their father, Bendahara Ali.

During those times, it was common to witness conflict between the children of rulers – brother against brother, nephew against uncle. This was due to individuals displaying acts of bravado and hoping to possess the wealth of their ancestors. Such can be said about the war between Wan Ahmad and Bendahara Mutahir.

The speed at which war breaks out was not a strange phenomenon in those times. It was the reality of life as reflected in this poem:

Pat-pat, the elbow folds,

Who is quick will acquire,

Who is late their eye will become mould,

Who is strong will become a king,

Who is knowledgeable will become a leader,

Those beautiful will be taken as concubines,

Those ugly will be enslaved,

Those who grovel will be pitied,

Those who are honest will freely die.

The weak are the food of the strong,

The foolish are the food of the intelligent.

Supporters from both sides ended up as casualties of the war. Many of those on Wan Ahmad’s side were injured and killed. The same can be said for the bendahara’s side. How the dead piled up during the war! But what can be said? For this was the reality:

Citizens must be loyal to their king,

Followers must believe in their leader,

Orders are followed – rebelling is prohibited.

To make matters worse, the people lived in fear of their powerful yet wicked rulers. Whoever dared to rebel was deemed a traitorous citizen. All the citizens were aware that their situation in the context of the war was like this Malay proverb: “Mousedeer die in between warring elephants.” Or as the Indians say: “Cows clash, yet it is the grass that perishes.”

It was not that they were unaware; those who were said to be their enemies and were supposed to fight to the death could be their siblings or in-laws, or even their fathers. But in such a difficult situation – “swallow and mother dies, do not swallow and father dies” – due to the self-importance of their kings and rulers, they were forced to fight in fear of being condemned as traitors.

Before attacking his brother, Wan Ahmad had brought his people from Pahang and Kemaman to Pulau Tekong in Singapore. It was on the island of Tekong that the people trained to become soldiers and learn the art of war. Wan Ahmad was in a hurry – if his soldiers succeeded in taking over Pahang, his brother’s rule would end and thus he could ascend to the sultanate of Pahang, replacing his brother as bendahara.

As Wan Ahmad’s men trained for the war, the army of the Lingga sultan, Mudzaffar Shah, who had been deposed by the Dutch government in Riau, arrived at Pulau Tekong. The sultan came to an agreement with Wan Ahmad to overthrow the Pahang sultanate. It was the sultan’s intention to be the new king of Pahang after Bendahara Mutahir had been defeated by Wan Ahmad’s army.

The Lingga sultan had brought with him a large entourage comprising the people of Lingga, Bentan and Daik. In this party was Mak Gobek, the princess’ governess. Her husband was Che’ Soman, who hailed from Daik. He was a talented violinist, and was also humorous and cheerful. Some also said that he was a warrior.

Che’ Soman, also known as Tok Sumang, had three sons with Mak Gobek. The eldest was Long Amat, the second, Che’ Mamat, and the youngest, Si Kemidin. The three of them were in the convoy as well.

After getting ready for war, the armies of Wan Ahmad and the Lingga sultan – with the help of the Terengganu army – sailed to Pahang and attacked the bendahara’s people, who were unprepared. The surprise invasion caught the bendahara off guard and he retreated to the edge of Pahang to organise his defences. He also requested assistance from his in-law, Temenggong Ibrahim of Johor.

With the help of the Johorean soldiers and weapons from the British East India Company in Singapore, the bendahara fought back against Wan Ahmad’s army.

Che’ Soman’s wit and cheerful disposition, along with his blind left eye, led his friends to draw parallels between him and the role Abu Nawas assumed for Sultan Harun Ar-Rashid. Che’ Soman was then given the name Tok Sumang by his friends. [Tok is a nickname for grandfather or grandmother.]

It is surely fictitious if we say that birds stop flying when they hear Tok Sumang playing the violin. However, if a lady hears the melodious notes of Tok Sumang’s violin and does not pause her work, it can be said that she is not a lady.

What is certain is that Tok Sumang was a part of the Lingga sultan’s convoy for the purpose of entertaining the sultan and his princess, and alleviating their worries. In addition, Tok Sumang was a medicine man who helped treat those who were ill in the convoy.

And so, for months, the two brothers waged war on each other, with no heed to the consequences and sacrifices…

Love for Peace

One day, Bendahara Mutahir yearned for a reconciliation with his brother, and thus consulted his advisors.

“As a brother, allow me to give in. There is no shame for me if I were to surrender the control of Pahang to Wan Ahmad. I desire to see a Pahang that is peaceful, harmonious and thriving,” said the bendahara to his assembly of advisors.

“Forgive me, my master,” said Haji Hasan, “How fortunate is Pahang to have a ruler who is as magnanimous as my master! Hopefully your kind spirit of humanity will flow through and be imbued in your descendants. Regardless, we are prepared to carry out your orders.”

The bendahara smiled at hearing Haji Hasan’s tribute and continued to seek the opinions of other advisors. After all of them gave their agreement, the assembly arranged for peace emissaries to negotiate with Wan Ahmad.

Haji Hasan was appointed to lead the delegation, and he chose Tok Jelai as his advisor.

One fateful day, Haji Hasan and his advisor, along with other elders, travelled to hold peace negotiations with Wan Ahmad. The emissaries were received kindly by Wan Ahmad, who chose Datok Lambak and a few other wisemen to be his representatives for the negotiations. Tok Sumang was also present in the negotiations as part of the Lingga sultan’s emissaries. Not only was he a talented violinist, Tok Sumang was also silver-tongued and skilled enough in negotiations to make wise decisions.

“Warring against one another has no benefit. If spears clash, krises strike, feuds pursued, it will be your people who will perish – my brother, your cousins, our in-laws,” said Haji Hasan, beginning the peace negotiations.

“True, true. It is true what the honourable Haji says,” said Tok Lambak, nodding while he stroked his beard. “However, what can we do to avoid such a tragedy? For we are all royal subjects, Malays who do not dare defy,” added Tok Lambak as he chewed the betel nut, his eyebrows furrowed.

Tok Sumang interjected, “It would be best if both parties agree to stop this conflict, destroy all forts, sheath their weapons and return to their peaceful lives, following the path blessed by Allah.”

“This is the best of paths: happiness in both this world and the hereafter,” said Tok Lambak, echoing Tok Sumang.

“But how can this be achieved when both our kings are still fighting over power? The customs of war dictate that a king dies along with his defeated nation. Otherwise, chaos will surely erupt,” said one of Tok Lambak’s companions.

“Be as it may, do not let the obscure future lead us to become as they say, ‘The winners become ash, while the defeated become coal.’ Especially when we all know that when ‘water flows with water, litter will be swept aside’.

“Now that the brother has sought peace, which has been well received by his younger sibling, let us not try to be too clever in negotiating and bartering until this clear situation is obscured. Let us together find a way towards peace as best as we can, in line with the proverb, ‘Let the beaten snake die, but not for the stick to break. Let not the land surface cave in.’”

This was the advice Tok Sumang gave to the assembly.

The negotiations continued with goodwill, until both sides finally reached a conclusion.

“The reconciliation of the two brothers will be immediate. Wan Ahmad would be appointed the bendahara of Pahang, replacing Wan Mutahir. The people of Wan Ahmad would halt in their looting and attacking of the bendahara’s people.”

These decisions were taken solely in consideration of the importance and welfare of Pahang.

After the negotiations, the party of Haji Hasan hastened back to convey the outcome to the bendahara, who was saddened to accept an outcome that would force him to leave his homeland. But for the sake of the welfare of the people of Pahang, he was prepared to accept the decision.

One day, the bendahara gathered his people and said: “I have lost the war. Most of my people are women who despise the destruction that this war has brought. And… I am sick of seeing all of you killing one another. Therefore, for the interest of the people and for the peace of Pahang, come – for those who want – and follow me in immediately distancing ourselves from the evils of war. The victor of this war – the one who has defeated me – is my own younger brother, Wan Ahmad, for whom I have willingly left the state to and the chance to rule Pahang.”

Silence befell upon all.

Those who were present at the gathering were speechless. None dared to raise their head to look at the bendahara – everyone was in contemplation, but their thoughts seemed obscured. The emissaries listened with patience and respect to the announcement that had been calmly conveyed.

Suddenly, eyes widened when one of the bendahara’s warriors, Wan Embong, approached bowing.

“Forgive me, my king. Why have we easily surrendered without fighting till the end? Your servant is dismayed and regretful that the war occurred when he was out of state. If he had been here, ‘let the bones whiten but not the eyes; be sure to be wet when bathing, be sure that the ink is visible when writing; hold onto the embers until they become coal’. But what can be done, for your command has fallen. Otherwise, at this very moment I would have slaughtered that traitor,” said the arrogant Wan Embong, as he bowed with flowing tears.

As soon as he heard Wan Embong’s words, which attempted to paint himself in a positive light, Haji Hasan interrupted.

“Forgive me, Your Highness. Your servant only accepted this good decision following the command of Your Highness.”

“Fool…,” mocked Wan Embong, challenging Haji Hasan. “Why have you sought to smear coal upon the face of Your Highness? If peace was the conclusion, should it not be that it is the young who are ruled by the elders? I despise how all of you have destroyed the ways of our ancestors!”

Those present were frightened by Wan Embong’s rage. The bendahara dismissed the gathering out of fear that an unfortunate incident might occur. He then proceeded to convene an assembly of warriors to reconsider the peace treaty.

The warriors decided that it is better to die on the battlefield than to live a life of shame. The defences of Wan Ahmad had to be destroyed immediately. Wan Embong was appointed the war commander and tasked to lead the army in attacking Wan Ahmad’s fort.

Wan Ahmad’s soldiers ferociously resisted Wan Embong’s army, as they felt that they had been deceived by the peace treaty with the bendahara’s people. From then on, the flames of war were stoked for the second time.

In Isolation

One night, while Tok Sumang was playing his violin as usual, the daughter of the Lingga sultan heard the melodious tune and was enchanted. From that night onwards, the princess would often visit Tok Sumang. Soon, rumours became rife among the people of Lingga and Daik that the princess had fallen in love with Tok Sumang.

The farcical story spread like wildfire when, one night, someone spotted the princess entering Tok Sumang’s room while Mak Gobek and their children were not at home. The story soon took on a life of its own.

That night, the princess outrightly told Tok Sumang that she had fallen in love with him, despite knowing that he was married with three children. The princess admitted as well that she had trouble sleeping at night thinking of Tok Sumang – “eat yet hunger persists, sleep yet tiredness remains”. Everything she did seemed strange.

The princess pleaded with Tok Sumang to take her as his wife.

She said, “Persimmon and jujubes, basil leaves I shall strip. Leave my mother and siblings, for my love I shall commit.”

Tok Sumang did not immediately accept or reject the princess’ confession of love. He asked for time to think and mull over her request.

He reasoned that as “the world turns as the sky lies, thinking wrongly will lead to becoming a slave”.

Fearing the repercussions, including the punishment he would face from the sultan for insulting the royal family, Tok Sumang quietly escaped with his family, leaving the encampment of Lingga in search of a peaceful place.

Although they had to endure difficulties in their journey – navigating rivers and traversing shores – Tok Sumang felt more at peace than living a comfortable life filled with trials.

After leaving the fort, Tok Sumang and his family began their new life on the outskirts, surviving on wild fruit and the flesh of hunted prey and fish. Nevertheless, the family’s life was peaceful and happy. Tok Sumang could always count on his violin to calm the worries of his family members, who had isolated themselves from others.

One night, while Tok Sumang was playing his violin, Mak Gobek said to him teasingly:

“Don’t you have something else to do other than playing that violin? If you have a pretty face, then at least you can be a theatre performer. But with your eye, you can’t be one, so there is no need to always play that thing.”

“Hey, you do not know the value of ‘art’, so there is no need to interfere in what I do. I do not care if I’m not given food, but do not prevent me from playing my violin. I feel at ease and satisfied when I play,” Tok Sumang replied.

Mak Gobek had no intention of picking a quarrel with her husband. The truth was that she loved listening to music from the violin, but she also liked to tease Tok Sumang, bantering with him to forget their exhaustion from the day’s work. It was said that Mak Gobek had been madly in love with Tok Sumang due to his violin skills. It was fortunate that Tok Sumang was still a bachelor at the time, otherwise she would not have been able to marry Tok Sumang.

Tok Sumang’s home was never fixed at one place. He and his family were always on the move depending on the circumstances. In other words, they would go wherever there was sustenance to be found. In the end, with the will of Allah, Tok Sumang and his family reached Pulau Tekong. It was the place where some of his friends – those who could no longer fight the war – had been left behind by the Lingga sultan. Some of the people from Pahang had also set up villages on the island.

It was said that the people of Pahang residing in these villages were mostly peace-loving and wished to avoid the war that was raging in their homeland at the time. They deemed that the proverb, “Though it rains gold and silver in the land of others, and it rains krises and spears in the homeland, it is still better to be in our homeland”, would not apply in such chaotic times.

Tok Sumang was recognised as the headman by the people from Riau and Lingga. He was known as a man of good character, vast experience and fair judgement. In addition, he was capable of treating and healing the sick.

If there was anyone who wished to organise a feast, they would consult Tok Sumang for an auspicious date and time. Those who went ahead without seeking counsel from Tok Sumang would feel regret and be dissatisfied.

If there were disputes among the island’s residents, they would look to Tok Sumang as the final arbiter to tell them what they needed to do. Tok Sumang would act as the judge, while Mak Gobek was the “lawyer”.

In summary, it can be said that Tok Sumang was a symbol for the people of Riau and Pahang who lived on that island. It was he who would:

purify what is unclean;

bring together those divided;

connect those from afar;

temper what is stiff;

soften what is hard;

cool what is hot.

Nobody ever questioned Tok Sumang’s words and actions. Whatever he said resonated with and was supported by the people. They all agreed that Tok Sumang was a wise man.

Establishing Kampong Punggol

After living on Tekong for some time, there came a day when Tok Sumang instructed his son, Long Amat – by then, all his children had become young men – to return to Daik and apprise their relatives of the situation.

Long Amat was also reminded to inform their relatives that Tok Sumang wished to establish a new village in neighbouring Singapore, which was covered with dense forests and home to crocodiles and snakes.

“Tell them that whoever wishes to live together with us can join you in your journey home,” Tok Sumang said to Long Amat.

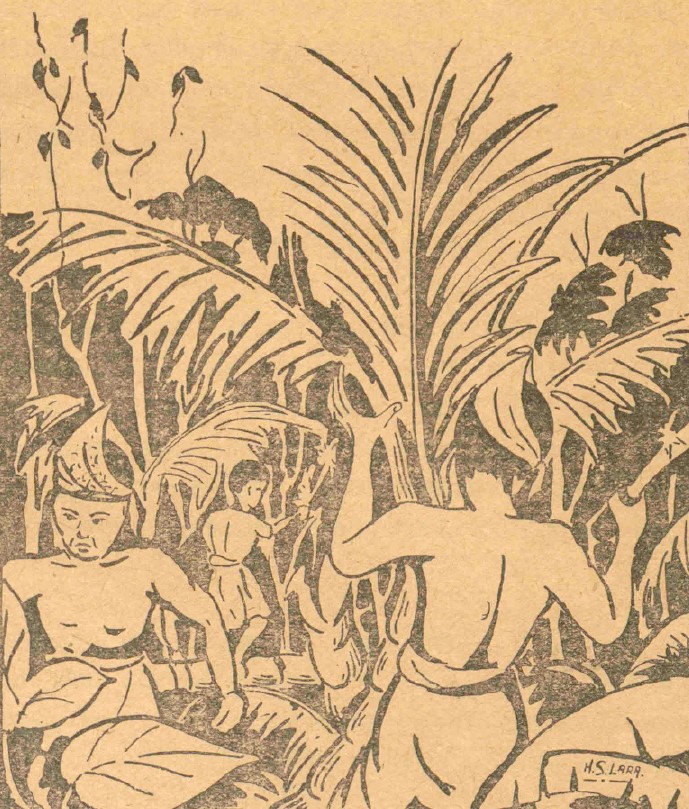

After Long Amat had sailed for Daik, Tok Sumang, along with his other sons, Che’ Mamat and Si Kemidin, rowed to neighbouring Singapore as planned. The trio of father and sons began their work: chopping trees, removing thickets and clearing the forests to plant coconut trees.

From Tok Sumang, p. 27.

For months they were hard at work, until the snake-infested forests were cleared and the coconut trees planted. They also chopped the many rumbia trees [sago trees] for the purpose of making sago that could be sold to Melaka and Pahang.

“A branch lives to bear fruit, while a person lives to be of benefit,” said Tok Sumang to his children one day while they were resting and eating fried sago fritters.

“Now, our land seems vast, father,” said Che’ Mamat.

“Yes. But we will expand it as best as we can. When your brother returns, we will divide the area,” replied Tok Sumang.

“If possible, let me take an area that is near that river, father, so it is easy to set traps,” said Si Kemidin, pointing his thumb in the direction of the river.

“Of course. Of course, as long as you put in effort, you will acquire what you wish,” said Tok Sumang, standing up while balancing his tanjak [a headgear for men]. “Let us continue working until we reach the area that is sought by Si Kemidin.”

The two obedient sons said nothing but rose and reached for their tools, before continuing to work. This was how they operated: sailing to the shore each morning and working tirelessly the entire day, only to return in the evening. Some nights when they had to work, Tok Sumang would play the violin. Hearing the melodious tune assuaged their fatigue, ensuring that they were ready to face a brand new day.

Thus was the life of Tok Sumang: always accompanied by his shovel and violin.

It was not long before Long Amat returned from Daik. Many of their relatives had accompanied him to Tekong. Some came because of longing, while others did because of existing problems back home. Yet others left Daik because they wanted to assist Tok Sumang in establishing a new village.

A week later, those from Daik travelled from Pulau Tekong to Singapore. There were 44 boats full of people, crowding the strait that separated the two islands.

Too beautiful was the sight of those boats;

Like fishes entering a wooden trap

Like the swordfish invading Singapore

Like doves flying as a flock

The oars sway with one rhythm —

The boats move in unison

The oars move as one like legs of centipedes

The oars splash, clearing the water.

Upon reaching Singapore, they cheered with jubilance. Incense was burned and smoke rose, enveloping Tok Sumang as he blessed the new village. Mak Gobek walked on his left, scattering yellow rice. After circumambulating the village, the feasting began.

Following the celebrations, the men erected makeshift places for them to sleep, also known as bangsal [shed]. The bangsal was elongated and roofed with leaves, without any walls. That night, everyone slept together in the bangsal. They did this as a sign of unity – that united they were strong and divided they were weak. They knew that it was only with unity that work could be completed with success.

The next morning, after a drink of water, Tok Sumang divided the cleared land into three parts.

The seaside area was given to Long Amat, the shoreside area to Che’ Mamat, and the riverside area to Si Kemidin – which is why the river there is now called Sungei Kemidin. Afterwards, everyone divided themselves into three groups: those who followed Long Amat lived by the sea, those who followed Che’ Mamat lived on the shore, and those who followed Si Kemidin lived along Sungei Kemidin.

One day, a white man from the Land Office came to the village together with an Indian man who was his interpreter. They asked for the headman or the leader of the village. One of the villagers brought the white man to Tok Sumang, who was chopping down the punggor (trunk) of a rumbia tree.

We don’t know what the white man said and how the interpreter explained his words. Although Tok Sumang was unable to understand what was being asked, he still replied to the white man’s queries.

“Sir, wait for me at my home, for I will return in a while. I am about to finish chopping the punggor of this rumbia,” he said, while directing his thumb towards his house.

Tok Sumang could not comprehend what the interpreter said to the white man, but he heard the white man repeatedly saying, “Ponggor… Ponggol…”

In the end, the village founded by Tok Sumang came to be known as Kampong Punggol.

Memories

One day in 1890, there came an officer who wanted to build a road in Punggol. According to plans by the government, the road would be laid across the plantations of Tok Sumang and his children. The officer wished to meet Tok Sumang, but the headman had passed away by then.

The officer was met by Long Amat. He explained that the government would provide financial compensation if Long Amat allowed them to build the road. Long Amat did not decide immediately. He requested the officer to make a second visit so that they could discuss the matter again. The officer agreed.

After the officer left, Long Amat consulted his brothers, Che’ Mamat and Si Kemidin. Si Kemidin wanted to know the amount of financial compensation from the government.

“A few thousand, but one day, even that amount will be used up,” Long Amat explained to Si Kemidin.

“What is there to this worldly wealth for us to be greedy? If the authorities want to carry out the project, let them as long as we are given compensation that is enough for our life,” said Che’ Mamat.

“That is true, but remember the advice of our late father: ‘The life of a tree brings fruit, the life of a person brings benefit!’” I think if we accept the money, it will be gone in a few months. What if we do not accept the compensation but ask the authorities to give us a guarantee that the land by this sea will not be taxed, so that our children and descendants can stay and live here without much burden?” said Long Amat.

The brothers agreed. Long Amat was relieved and waited for the arrival of the officer to give an answer as he had promised.

The officer finally arrived and asked for Long Amat’s answer. Long Amat informed him of the decision that the siblings had made after much discussion. This was received well by the officer. The guarantee was thus given, and the construction of the road was slated to begin soon.

In early 1891, the construction began. Kampong Punggol was given to Long Amat as land that would never be taxed. For that reason, the villagers of Kampong Punggol Laut do not pay tax until now.

In memory of Tok Sumang, the road that was built leading to the shore of Tanjong Punggol was named “Jalan Wak Sumang”.

The End

After reading the tale of Tok Sumang, let us recite Surah Al-Fatihah [a prayer] upon his departed soul in tribute to his legacy and leadership. We seek from Allah to bless us with more Malay leaders with qualities like Tok Sumang, who prioritised the affairs of his kinsfolk and people, rather than his own affairs.