Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees: A Rediscovered Manuscript

A forgotten manuscript found in the archive of a Portuguese museum offers insights into the languages and traditions of a unique community in the Dutch East Indies.

By Hugo C. Cardoso

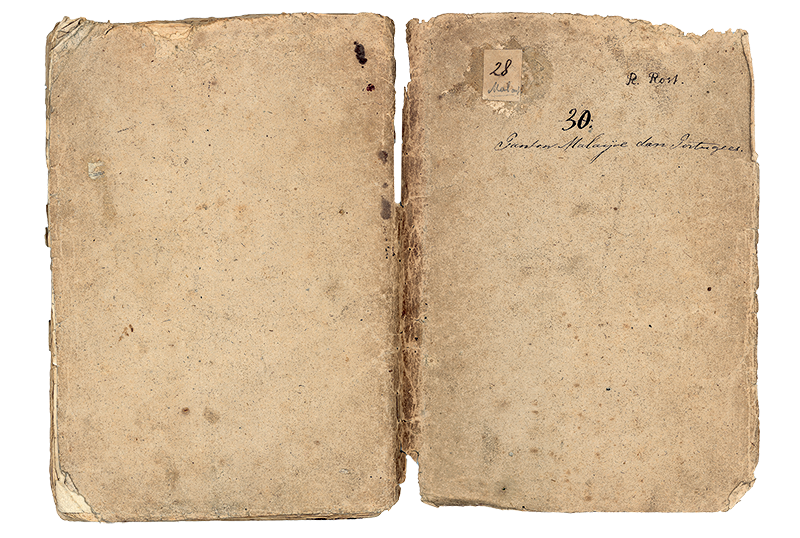

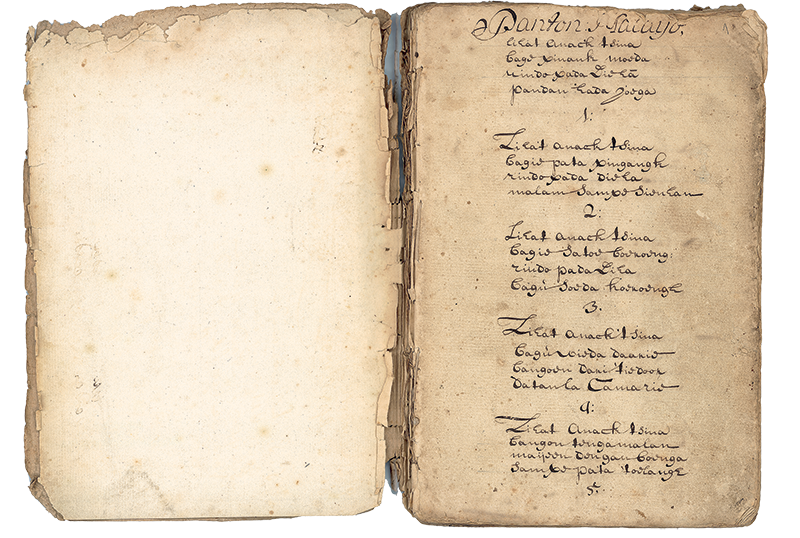

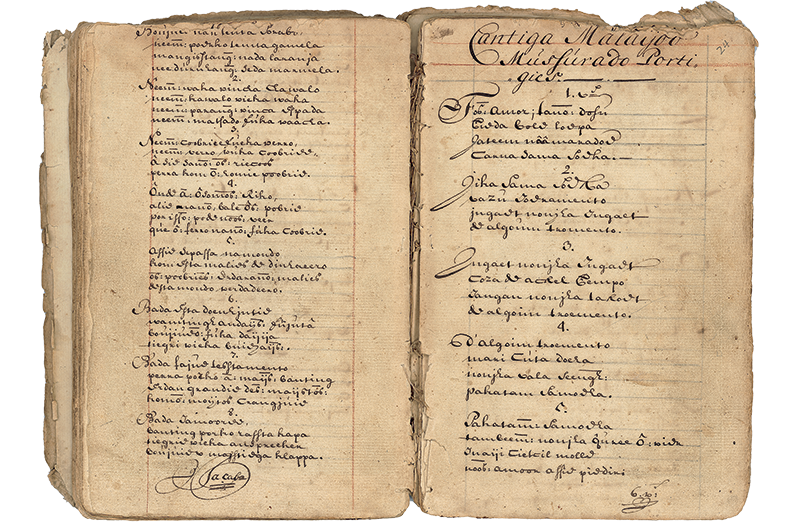

Some time around 1865, in the storeroom of Bernard Quaritch’s antique bookshop in London, an employee rummages through stacks of documents in search of a manuscript to be delivered to Ernst Reinhold Rost, the secretary to the Royal Asiatic Society and a regular client. When the manuscript finally emerges, it does not look particularly distinctive. It is comparatively small in size (21 × 14.5 cm) and length (39 folios), and is encased in rough, undecorated paper bearing an intriguing handwritten title in Malay: Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees (Malay and Portuguese Pantun).

The employee takes a moment to leaf through the item and notices it contains a number of texts resembling poems, organised in quatrains. Some are written in what appears to be a variety of Malay and identified by their titles as “Pantoons”, while others are called “Cantigas” and rendered in a language that looks decidedly Romance, at least as far as words are concerned. So, judging from the manuscript’s title, perhaps Portuguese? There is even one text that mixes both, with each alternating verse in a different language. Whatever it may be, the manuscript is due to be picked up fairly soon, so the employee packs it carefully and places it on the despatch desk.

This episode may be slightly fictionalised here, but its essential components are factual and correspond to the moment in which the trajectory of this manuscript, Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees, first becomes traceable on the basis of the documentary evidence available so far.

After the manuscript was acquired by Rost, it went on to have a number of different owners until it finally wound up in the vaults of Portugal’s Museu Nacional de Arqueologia (National Museum of Archaeology) in Lisbon, where it languished for a number of decades before resurfacing in 2018. The significance of this discovery would eventually lead to the 2022 publication of Livro de Pantuns (Book of Pantuns). This bilingual book, edited by a team of five of which I was a member, provides contextual studies on the history of the manuscript as well as the verses inside, with explanations and annotations, and the Portuguese and English translations of the verses.1

The journey of the manuscript from a London bookshop to the Lisbon archive was marked by stops and starts. After its acquisition by Rost, the manuscript ended up circulating within a network of European philologists who realised its importance as a linguistic record, especially with respect to the sections identified as “Portuguese”, which they recognised as a rare sample of a Portuguese-lexified creole (a language resulting from substantial contact between Portuguese and other languages) from Insular Southeast Asia.2

The Manuscript Changes Hands

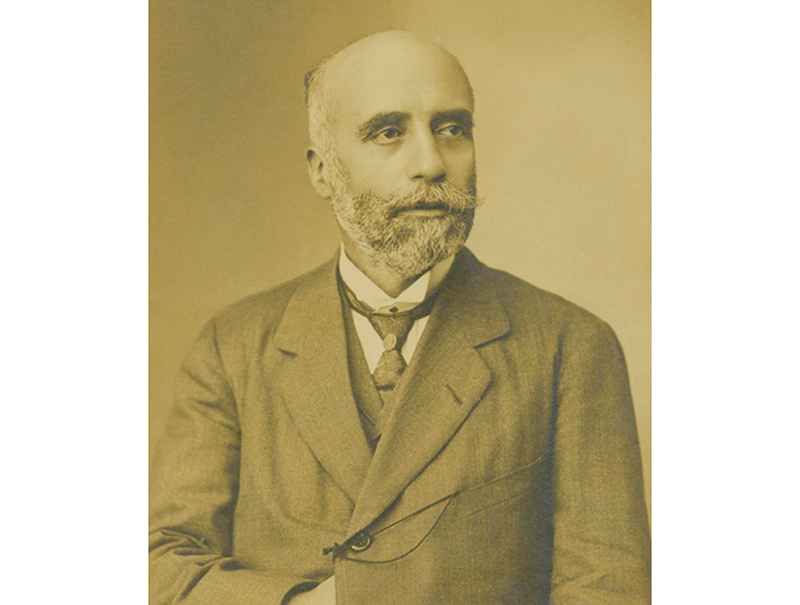

Interestingly, the initial protagonists of the manuscript’s recorded history were all Germans. The antique bookseller Quaritch was German, as was Rost, an orientalist specialising in Asian languages (such as Sinhala and Malay) and literature. Rost spent most of his career in England, where in addition to his position with the Royal Asiatic Society, he was also a librarian at the India Office.

The other important German who played a central role was the eminent linguist Hugo Schuchardt, a prominent figure in the history of linguistics. He spent most of his career at the University of Graz in Austria and had an extraordinarily vast range of scientific interests encompassing Romance languages, the Basque language, and the dynamics and effects of language contact. To pursue all of these, Schuchardt developed a vast global network of correspondents from whom he obtained linguistic data and relevant sources. Rost was one of them.

The correspondence between the two men reveals that Rost sent the manuscript to Schuchardt in 1885 as a loan and 10 years later, shortly before his death, turned that loan into a gift.3 Schuchardt, who was particularly interested in Portuguese-lexified creoles, realised the manuscript must have represented the variety spoken in and around colonial Batavia (present-day Jakarta), a language for which he had amassed other relevant sources.

In 1890, Schuchardt published a lengthy article about this particular Portuguese Creole language, titled Über das Malaioportugiesische von Batavia und Tugu (On the Malayo-Portuguese of Batavia and Tugu), in which he transcribed and analysed all the linguistic data he had collected except for that contained in Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees. The omission of the manuscript was not an oversight nor a belittlement of its relevance. Quite the opposite, in fact. In his published text, while discussing a dialogue transcribed in a 1692 work by George Meister, Schuchardt remarked:

Etwa aus derselben Zeit als die Meisterische Probe stammt eine handschriftliche Sammlung malaioportugiesischer und malaiischer Pantuns, die ich schon wegen ihres Umfanges für eine besondere Veröffentlichung aufsparen muss.4

[From approximately the same period as Meister’s text, there exists a manuscript collection of Malayo-Portuguese and Malay Pantuns which, in view of its size, I am reserving for a separate publication.]

Sadly, this follow-up study never materialised. In the meantime, the manuscript caught the attention of another prominent scholar: the Portuguese doctor, philologist, ethnographer and archaeologist José Leite de Vasconcelos. He was another of Schuchardt’s regular correspondents and the two actually met in 1900 in Graz, where Vasconcelos was given the opportunity to consult the manuscript. He was intrigued by it and, a few years later, asked Schuchardt for a copy of its contents.

As we gather from their correspondence, this request was not well received by Schuchardt since he was still planning to publish a substantial study of Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees.5 However, he eventually decided to bequeath the document to Vasconcelos. After Schuchardt died in 1927, the manuscript was despatched to Lisbon. Even though Vasconcelos clearly intended to work on it, he never published a study on the document either. As a result, despite various references to the manuscript and the clear interest shown by some of the leading early scholars of language contact, its contents remained a mystery until very recently.

Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees Resurfaces

Vasconcelos was a leading figure in Portugal’s academic scene of the early 20th century, developing fundamental research and many initiatives that still resonate in the country to this day. One of these was the establishment in 1893 of the Museu Etnológico Português (Portuguese Ethnological Museum), the predecessor of the modern Museu Nacional de Arqueologia (MNA). Vasconcelos was the director of the museum for many decades, which explains why the MNA’s archive now holds part of his personal archive – a large collection of publications, letters, fieldwork documents and manuscripts.

One of those manuscripts is Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees, but this was not confirmed until 2018 when Ivo Castro, a fellow professor at the University of Lisbon, and the MNA’s librarian, Lívia Coito, stumbled across it while rifling through a number of boxes in the archive.6 Aware of the history of the manuscript and of its scientific value, Castro shared the news with me and we invited three other specialists – Alan Baxter, Alexander Adelaar and Gijs Koster – to collaborate in a comprehensive study of the manuscript. Over the following three to four years, the team worked jointly and finally published Livro de Pantuns (Book of Pantuns), a bilingual (Portuguese and English) book dedicated to the manuscript.

The core of Livro de Pantuns consists of an edition of the manuscript with a transcription of its contents (plus, in the case of the Malay texts, a proposed textual reconstruction and a version in modern Bahasa Indonesia). It also has proposed translations into Portuguese and English, with comprehensive footnotes containing commentaries about the manuscript and the authors’ analyses. The book also includes a full facsimile reproduction of the manuscript and four chapters in which the five authors explore various aspects of the document – namely the history and materiality of the manuscript, as well as the linguistic and literary characteristics of the Malay pantun and the Portuguese Creole cantigas (a Portuguese term for “song”).

Tracing the Genesis of the Manuscript

Since Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees is undated and makes no reference to a place of production, determining who may have been responsible for compiling the manuscript is a challenge. Schuchardt was convinced that it had been produced in Batavia sometime in the late 17th century, and he was probably right. Various hints point to Batavia, which was the epicentre of the Dutch East Indies between the 17th and 20th centuries. The use of northern European-produced paper, European-style calligraphy and some Dutch-like orthographic solutions all suggest a European-influenced environment that would have been found in Batavia at the time.

In principle, a collection of Malay and Portuguese Creole pantuns could also have been produced in other Dutch-controlled locations of Southeast Asia (such as Melaka), but Batavia emerges as the most likely source. This is evidenced by the abundance of references in the texts to Java, in the form of toponyms (such as Banten, Tangerang and Batavia itself), fruit, plant and food names, and even historical events.

The language in the texts also has links with Java’s linguistic ecology. In the Malay-language texts, a few forms are more readily recognisable as reflections of Javanese words than Malay/Indonesian words, while the language of the Portuguese Creole texts is especially reminiscent of the Batavia and Tugu samples published by Schuchardt and recorded in a few other complementary sources.7

Having established (with a fair amount of certainty) that colonial Java was the most likely setting for the production of the manuscript, we are still left with the issue of dating the document. In this respect, all we can say for sure is that the manuscript could not have been completed before 1690.

This insight is based on two historical episodes referenced in the pantun. The Portuguese Creole text, Cantiga de Tangerang mais Bantam (Song of Tangerang and Banten), narrates the conflict between Sultan Abu’l-Fath ‘abdu’l-Fattah (Ageng Tirtayasa) of Banten and his son, Abu Nasr Abdul Kahhar (Sultan Haji), which saw the involvement of the Dutch East Indies Company in 1682.8 Another pantun, the Malay-language Panton Joncker (Jonker Pantun), describes events relating to the presumed rebellion of Captain Jonker, an Ambonese serving in the Dutch colonial army, which took place in 1689, culminating in his death that year and the deportation of his children to Ceylon in 1690.9

While it is impossible to tell how long after these events the texts were written, the amount of detail suggests their memory may have been fairly fresh. Therefore, it is quite possible that the manuscript was completed in the late 17th century or the early 18th century.

It is also unclear whether the people who produced the manuscript were the ones who transcribed these originally oral texts or whether they worked on the basis of earlier written records. Either way, we do know the process must have been collaborative as an analysis of the calligraphy reveals that different sections were produced by different writers. That said, they certainly obeyed a masterplan because despite the multiple copyists, the result is a cohesive document in terms of form and content.

The Collection of Pantun

Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees contains 11 discrete and different-sized sequences of quatrains (identified in our publication with letters A through K for ease of reference), most with their own title and an explicit indication of their endpoint:

A - Panton Malayo (Malay Pantun): 43 stanzas in Malay;

B - Pantoon Malaijoo Naga Patanij (Malay Pantun from Naga Patani): 72 stanzas in Malay;

C - Cantiga de Amooris de Minha Manhonha (Love Song About My Wicked Lady): 76 stanzas in Portuguese Creole;

D - Cantiga de Tangerang mais Bantam (Song of Tangerang and Banten): 29 stanzas in Portuguese Creole;

E - Cantiga di Vooi Cada Noijto Majinadoo (Song of [I] Went Every Night, Pondering): 22 stanzas in Portuguese Creole;

F - [untitled]: Eight stanzas in Portuguese Creole;

G - Cantiga Malaijoo Mussurado Portigies (Malay Song Mixed With Portuguese): 19 stanzas combining Malay and Portuguese Creole;

H - Cantiga de Portugees Mais Mojeers os Omis Casadoe (Portuguese Song About Married Women and Men): 30 stanzas in Portuguese Creole;

I - Pantoon Malayo Panhiboeran Hati Doeka Dan Piloô (Malay Pantun to Cheer Up the Sad and Melancholic Heart): 18 stanzas in Malay;

J - Panton Dari Sitie Lela Maijan (Pantun About Siti Lela Mayang): 29 stanzas in Malay; and

K - Panton Joncker (Jonker Pantun): 30 stanzas in Malay.

Thematically, these texts are not dissimilar to the wider Southeast Asian genre of the pantun, while simultaneously establishing links with European literary traditions, including chivalric literature and medieval Portuguese love poetry.10 Love (whether licit or illicit, consummated or aspirational, joyous or painful) is the theme of several of them, as exemplified by the following excerpt from the opening sequence of Panton Malayo:11

[…]

Lihat anack tsina

Toehan kie tsilmoele

rindo pada dieha

makan tida boole.

Lihat hanack tsina

bagú wida darie

roepa bage boenga

bangoen la camarie.

Soeda amba casie

djúwa dengan badangh

boehat la canda tie

bagi sooka toehan.

[…]

Behold the Chinese maiden,

The dainty little lady.

I long for her,

Unable to eat.

Behold the Chinese maiden,

Beautiful like a heavenly nymph.

Pretty like a flower

Get up and come here.

Your servant has given

Body and soul

To fulfill his wish

To please you, my lady.

Other texts have a moral undertone, using various rhetoric strategies to reflect on society and human behaviour. The untitled sequence F is one such case. As seen in the excerpt below, the text is both metaphorical and explicit in denouncing the inescapability of social inequalities:12

[…]

Neem: waka wincha chawalo

neem: kawalo wieka waka

neem: parang: winca ispada

neem: matsado fúka waacha.

Neem: coobrie fúeka werro,

neem: verro wúka coobriee,

âsie sauõ: os: riecoos

perra kom õ: homie poobrie.

Ônde ā: ô somos: Riko,

alie nanõ: bale ôs: pobrie

por isso: pode noos: veer

que ô: ferro nanõ: fuka coobrie.

[…]

Neither will the cow turn into a horse

Nor will the horse turn into a cow;

Neither will the machete turn into a sword,

Nor will the axe turn into a knife.

Neither will copper turn into iron,

Nor will iron turn into copper.

So are the rich

Towards the poor man.

Where the rich are,

There the poor do not go.

Hence we can see

That iron does not turn into copper.

Some sequences have a narrative structure. In addition to the ones that recount historical events, others are (or appear to be) fictional. The sequence titled Panton Dari Sitie Lela Maijan – which, as Gijs Koster notes, shows similarities with other pantuns recorded elsewhere – tells the story of a married woman’s extramarital relationship with a young man identified by the name of Kosta, set in a place that may be recognised as the city of Batavia.13 The following section narrates Siti Lela Mayang’s escape to join Kosta:14

[…]

ada satoe anack ôrangh

nama sitie lela maijangh

anak pego baroe datangh

goendik tjanko china qúijtangh

Poera poera pangeel kaka

ambeel gamparang pigie kalie

poera poera tjoetjie kakie

darie tanga Soeda Larie.

Lakie china datang tjarie

banting tangan banting kakie

mana nonja bida darie

nonja lari godong padrie

[…]

There was a young maiden

Whose name was Siti Lela Mayang.

She was a girl from Pegu who had just arrived,

The concubine of a Cantonese trader in jewelry.

Pretending she went to call her older sister,

She took her wooden clogs and went to the river.

Pretending she went to wash her feet,

She already started running on the stairs.

When her Chinese husband came looking for her,

He slapped his arms and slapped his legs:

“Where is my wife, that heavenly nymph?

Has she run off to the stone building of the fathers?

This very short tour of the contents of Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees reveals a poetic tradition of some thematic and rhetorical complexity. But whose tradition was it? The multilingual nature of this collection gives us some clues. In theory, different sequences could have been associated with different communities, and it can even be hypothesised that the Malay texts and the Portuguese Creole texts represent distinct traditional repertoires. However, the bilingual sequence G, Cantiga Malaijoo Mussurado Portigies, calls these possibilities into question. Consider the following excerpt:15

Fos: amor: tanõ: dosu

tieda bole loepa

jateem nôâ maradoe

carna sama soeka.

Jika sama soeka

vazu joeramento

jngaet nonjha Ingaet

de algoúm tromento.

Jngaet nonjha Jngaet

coza de ackel tempo

Jangan nonjha takoet

de algoum troemento.

[…]

Your love is so sweet

I cannot forget it,

It has tied us together

Because we like each other.

If we like each other,

You must swear an oath,

Be mindful, my lady, be mindful

Of the suffering [it may bring].

Be mindful, my lady, be mindful

Of the things [we did] at that time.

My lady, don’t be afraid

Of the suffering [it may bring].

Here, each quatrain is made up of alternating verses in Malay (transcribed here in italics) and verses in Portuguese Creole, interwoven in such a way that individual sentences, which often extend across several verses, combine both languages. Such a text would only have made sense to a group of people with command of both Malay and Portuguese Creole. In 17th- and 18th-century Batavia, only one community fitted the bill.

The Mardijkers of Batavia

Due to its centrality within the Dutch-controlled networks in Asia, early colonial Batavia had a highly composite population. One of the most prominent groups residing in and around it in the 17th century was given different names, but consistently described in terms that highlighted its connection with the Portuguese. The Portuguese had preceded the Dutch as colonialists in Asia, and competition between the two throughout the 17th century saw several Portuguese strongholds in different parts of the continent (such as Melaka, Cochin and Ceylon) pass into Dutch hands. As a result, many inhabitants of those conquered locations converged onto Batavia, often in a condition of servitude.

While associated with the Portuguese, these individuals were most likely Eurasian or Asian converts to Catholicism (as suggested by the Dutch moniker Zwarte Portugesen, translated as “Black Portuguese”).16 They carried along with them different previously formed Portuguese-lexified creole languages, out of which developed Java’s very own variety recorded in six of the pantuns in the manuscript.17

As this group of people attained autonomy within the Dutch colonial society, they eventually came to be classified as Mardijkers – an ethnonym derived from the Sanskrit-derived Malay term merdeka, which means “free men” – and made up a big portion of the Batavian population. According to accounts from the 1670s, Mardijkers were the largest group within the city.

Throughout the 17th and part of the 18th centuries, “Portuguese” was often described as one of the main languages used in Batavia but, more often than not, the term actually referred to the Portuguese-based creole developed by and associated with the Mardijkers.18 According to most accounts, the Portuguese Creole variety of Java lasted the longest in Tugu (previously a discrete village near Batavia and currently integrated in Greater Jakarta), but is no longer used as a vital spoken language, despite being preserved in certain oral traditions.19 As such, virtually all the linguistic evidence available for this language is archival. Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees is thus particularly important as it considerably expands the set of data available for this language.

This particular Portuguese Creole is not the only language that Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees sheds light on. Assuming that the Malay-language texts of the manuscript stem from the same oral repertoire as the Portuguese Creole ones, this document provides a rare glimpse into the type of Malay – or, at any rate, a type of Malay – used by the Mardijker community of Batavia.

In his study, Alexander Adelaar interprets the manuscript’s Malay-language pantun as a sample of Mardijker Malay and identifies a number of commonalities with contact varieties of Malay (known by many different names, including Bazaar Malay [Melayu Pasar], Low Malay or, in the linguistic literature, Vehicular Malay). These include, for instance, a possessive construction with punya (as in kieta poenha nanje, or “our song”) or a preposition pigi indicating the goal of movement (as in Sieti jalang pigie pasaer, or “Siti went to the market”).20

In addition, Adelaar also notes that certain phonetic characteristics of the manuscript’s Malay (such as the loss of the final -h, as in roema for rumah, meaning “house”, and of some final consonants, as in banja for banyak, meaning “much” or “many”) are especially reminiscent of forms of Vehicular Malay from eastern Indonesia, including in areas such as Maluku and Sulawesi. This observation underscores the relevance of eastern Indonesian communities and their varieties of Malay in colonial Batavia and their impact on the resident Mardijkers.

An Open Book

Panton Malaijoe dan Portugees has travelled a long way, from Batavia in Asia to Lisbon in Europe, where it is a material reflection of the not-always-obvious historical links connecting Indonesia and Portugal. Its diverse, multilingual texts speak of certain undercurrents that carried people, languages and traditions across coastal Asia but remain poorly understood, as they are only very faintly recorded in primary sources.

The sudden discovery of this manuscript promised to shed some light on the Mardijkers of Batavia and answer some pertinent questions: What was the exact composition of the community and how was it formed? How did the Mardijkers contribute to the cultural and linguistic mix of colonial Batavia? What were their daily lives like and who did they contact within the city? What were their takes on the prevailing social and political structures?

The research leading up to the publication of Livro de Pantuns was an initial effort by the editors to tap into the manuscript’s ability to clarify these and other questions – in particular, from a linguistic and literary perspective. However, aware that its lessons were far from exhausted, the team worked towards making the manuscript available to the public in a format that would allow further exploration. Hopefully, its 39 folios will still teach us a great deal.

Hugo C. Cardoso is an Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Lisbon (Portugal) and a researcher of language contact involving Portuguese in Asia, with a particular focus on the Portuguese-lexified creoles of India and Sri Lanka.

Hugo C. Cardoso is an Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Lisbon (Portugal) and a researcher of language contact involving Portuguese in Asia, with a particular focus on the Portuguese-lexified creoles of India and Sri Lanka.Notes

-

The data conveyed in this text is based on collaborative research conducted by Ivo Castro, Hugo Cardoso, Alan Baxter, Alexander Adelaar and Gijs Koster leading up to the publication of an edition and study of the manuscript. See Ivo Castro, Hugo C. Cardoso, Alan Baxter, Alexander Adelaar and Gijs Koster, eds., Livro de Pantuns: Um Manuscrito Asiático do Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Lisboa = Book of Pantuns: An Asian Manuscript of the National Museum of Archeology, Lisbon (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, 2022). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 899.281 CAS). ↩

-

For a fuller account of the manuscript’s history and characteristics, see Ivo Castro and Hugo C. Cardoso, “O Manuscrito de Lisboa,” in Livro de Pantuns: Um Manuscrito Asiático do Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Lisboa, ed. Ivo Castro et al. (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, 2022), 95–114. ↩

-

Hugo Schuchardt’s epistolar corpus is preserved at the University of Graz, and has been studied and digitised as part of a project led by Prof Bernhard Hurch. See “Hugo Schuchardt Archiv,” last accessed 2 June 2023, https://gams.uni-graz.at/context:hsa. ↩

-

Hugo Schuchardt, “Kreolische Studien IX. Über das Malaioportugiesische von Batavia und Tugu,” Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Philosophisch-historische Classe 122 (1890): 17. ↩

-

The correspondence between Schuchardt and Vasconcelos is published in Ivo Castro and Enrique Rodrigues-Moura, eds., Hugo Schuchardt / José Leite de Vasconcellos. Correspondência (Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press, 2015), https://fis.uni-bamberg.de/handle/uniba/39832. ↩

-

The discovery was first reported in Ivo Castro, Hugo C. Cardoso, Gijs Koster, Alexander Adelaar and Alan Baxter, “The Lisbon Book of Pantuns,” O Arqueólogo Português series V, 6/7 (2016–2017): 315–17, https://www.museunacionalarqueologia.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/Book-of-Pantuns.pdf. ↩

-

An edition and study of these sources can be found in Philippe Maurer, The Former Portuguese Creole of Batavia and Tugu (Indonesia) (London/Colombo: Battlebridge, 2011). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 469.79968 MAU). For a linguistic analysis of the Portuguese Creole texts in the manuscript, see Alan Baxter and Hugo C. Cardoso, “The ‘Panton Portugees’ of the Lisbon Manuscript,” in Livro de Pantuns: Um Manuscrito Asiático do Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Lisboa, ed. Ivo Castro et al. (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, 2022), 115–29. ↩

-

See Baxter and Cardoso, “The ‘Panton Portugees’ of the Lisbon Manuscript,” 119. ↩

-

For a more detailed account, see Gijs Koster, “The Poems in Malay in the Livro de Pantuns: Some Social, Historical and Literary Contexts,” in Livro de Pantuns: Um Manuscrito Asiático do Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Lisboa, ed. Ivo Castro et al. (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, 2022), 141–46. ↩

-

For a description of the Portuguese Creole sequences, see Baxter and Cardoso, “The ‘Panton Portugees’ of the Lisbon Manuscript,” 115–29. For a study of the Malay-language sequences, see Gijs Koster, “The Poems in Malay in the Livro de Pantuns: Some Social, Historical and Literary Contexts,” 131–47. ↩

-

Transcription and proposed translation reproduced from Castro et al., Livro de Pantuns, 248–49. ↩

-

Transcription and proposed translation reproduced from Castro et al., Livro de Pantuns, 310–11. ↩

-

In his chapter in Livro de Pantuns (p. 139), Gijs Koster identifies similarities between this text and Syair Sinyor Kosta, a poem that circulated widely in the Malay World in the early 19th century, four versions of which have been collated and studied. See A. Teeuw, R. Dumas, Muhammad Haji Salleh, R. Tol and M.J. van Yperen, eds., A Merry Senhor in the Malay world: Four Texts of the Syair Sinyor Kosta (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2004). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 899.281009 MER). As Koster notes, the manuscript’s version may actually be a much earlier attestation of this poem. ↩

-

Transcription and proposed translation reproduced from Castro et al., Livro de Pantuns, 334–35. ↩

-

Transcription and proposed translation reproduced from Castro et al., Livro de Pantuns, 314–15. ↩

-

For a fuller description of the Mardijker community, see Koster, “The Poems in Malay in the Livro de Pantuns: Some Social, Historical and Literary Contexts,” 131–32; Maria Isabel Tomás, “The Role of Women in the Cross-pollination Process in the Asian-Portuguese Varieties,” Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 8, no. 2 (December 2009): 49–64, https://jpl.letras.ulisboa.pt/article/id/5575/. ↩

-

For an overview of the Portuguese-lexified creoles of Asia and the Pacific, see Alan Baxter, “Portuguese in the Pacific and Pacific Rim,” in Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas, vol. 2, ed. Stephen A. Wurm, P. Mühlhäusler and Darrell Tryon (Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1996), 299–338. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RUR 402.23 ATL); Hugo C. Cardoso, “Contact and Portuguese-lexified Creoles,” in The Handbook of Language Contact, 2nd ed., ed. Raymond Hickey (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2020), 469–88; João Oliveira, “Portugal’s Linguistic Legacy in Southeast Asia,” BiblioAsia 19, no. 1 (April–June 2023): 40–47. ↩

-

That is not to say that Portuguese was absent from colonial Batavia. In fact, the first Portuguese-language translation of the Bible, undertaken by João Ferreira de Almeida, was completed in Batavia in the late 17th century. ↩

-

See for example Raan-Hann Tan, Por-Tugu-Ese?: The Protestant Tugu Community of Jakarta, Indonesia (PhD diss., Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, 2016). ↩

-

Examples and analysis from Alexander Adelaar, “Spelling and Language of the Malay Used in the Livro de Pantuns,” in Livro de Pantuns: Um Manuscrito Asiático do Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Lisboa, ed. Ivo Castro et al. (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, 2022), 149–59. ↩