Singapore's Got Talent: When Talentime Ruled the Airwaves

Although Talentime has been replaced by reality talent contests, it will be remembered as a show that launched the musical careers of many Singaporeans.

By Jamie Lee and Mark Wong

In its heyday, Talentime was a major cultural phenomenon in Singapore. Through radio, and later television, the talent show gave aspiring singers and bands a chance to make it big on the national stage. In the 1960s, The Crescendos and The Quests were picked up by record labels after being talent-spotted on the show. Singer Jacintha Abisheganaden got her big break when she won the contest in 1976 as part of the group Vintage.

Its hold on the public’s imagination, at least at one point, was remarkable. “[T]he first year that we put Talentime on to [sic] television [in 1967], there was no traffic on the road,” recalled veteran broadcaster Vernon Cyril Palmer in his oral history interview. “All traffic came to a halt. Anybody who was near an electronic shop would stop by and watch the programme through the display window. And most people stayed at home to watch the programme. That was how effective Talentime was.”1

The history of Talentime goes back to the early postwar years. In January 1949, Radio Malaya Singapore – one of Singapore’s earliest public radio services – released the results of a listeners’ survey. It found that people enjoyed “request programmes, dance and Hawaiian music and variety shows employing local talent” and they disliked “too many news bulletins, the stock market news and broadcasts of church services”.2 Later that month, the station announced that they were hosting a talent competition to discover Singapore’s “hidden talent” by inviting amateur artistes including singers, vocal groups, instrumentalists and even impersonators to compete in a series of six rounds.

“This is a chance for Singaporeans to show what they can do,” said Tony Beamish, Radio Malaya’s English programmes supervisor in the Straits Times. He said he hoped to have “many new voices over the air through discoveries for these programmes”.3 Performances would be held fortnightly, recorded in front of a live audience on a Friday, then aired on radio the following Monday.4

Beamish had been the one to come up with the name Talentime. “[The name] ‘Amateur Hour’, it wasn’t good enough,” recalled Palmer. “So we went through many titles and eventually we came up with the suggestion of ‘Talentime’. Actually it was suggested by Tony Beamish. We all agreed it was a good title.”5

The winner of the first Talentime round was 32-year-old Eurasian clerk Freddie Jansen, who sang “Surrender”. He “clocked highest on the applause meter” at the show on 18 February 1949.6 “Crooning is again the rage in Singapore,” trumpeted the Sunday Times. “With the introduction of Radio Malaya’s ‘Talentime’, the crooners and their soft mellow voices will no longer be confined to the microphones of the amusement parks and cabarets – or the bathrooms. Crooners will compete with each other in ‘Talentime’, and over the ether will come the voices of Singapore’s Bing Crosbys, Frank Sinatras and Perry Comos.”7

It turns out that the Straits Times was mistaken that the future was crooning. On 27 April 1949, Larry Fenton and his Tin Can Toledos took the winner’s title at the first Talentime finals. The Tin Can Toledos were not crooners. Instead, they were a “cowboy novelty act in which Larry… sang, yodelled, did vocal gymnastics and impressions”.

The finals were held at the Victoria Memorial Hall and a thousand-strong audience came to watch while thousands more listened to the subsequent broadcasts.8 It was so popular that 200 forged tickets were collected, in addition to the 850 officially issued tickets.9 (Remarkably, some five decades later, Larry would go on to win the first prize in Singapore Broadcasting Corporation’s Talent Quest in February 1989. Then 73, he gave a “gutsy impersonation of a radio broadcasting station”.10)

The Young Ones

Talentime benefitted from the growing popularity of rock ’n’ roll, which introduced an electrifying new culture of consuming music that was energetic, raucous and youth-oriented. By the 1950s in Singapore, “a healthy rock ’n’ roll culture was already in place”, paving the way for the “diverse and lively” pop music scene in the 1960s.11

Then there was the element of audience participation. This gave ordinary people the power to decide the winners. “The audience were the judges,” said 1952 Talentime winner Sam Gan Tiang Choon. “They were asked to clap after each contestant’s name was announced. An applause meter measured who won the loudest applause, hence the winner.” As a result, noted Gan, “nobody would risk a lengthy number and bore the audience to sleep. After all, they were the ones who decided our fate.”12

At least in the early years, the atmosphere was relaxed. “There were no rehearsals,” Gan recalled. “We just turned up and banged it out.”13 According to Reginald (Reggie) Verghese of The Quests, during the band’s 1963 Talentime experience, their “[g]uitars were out of tune. [Music director] Charlie Lazaroo threw us out. You know, there were no tuners at that time. So we tuned, then in the air-con, somebody’s guitar [goes] slightly out.”14

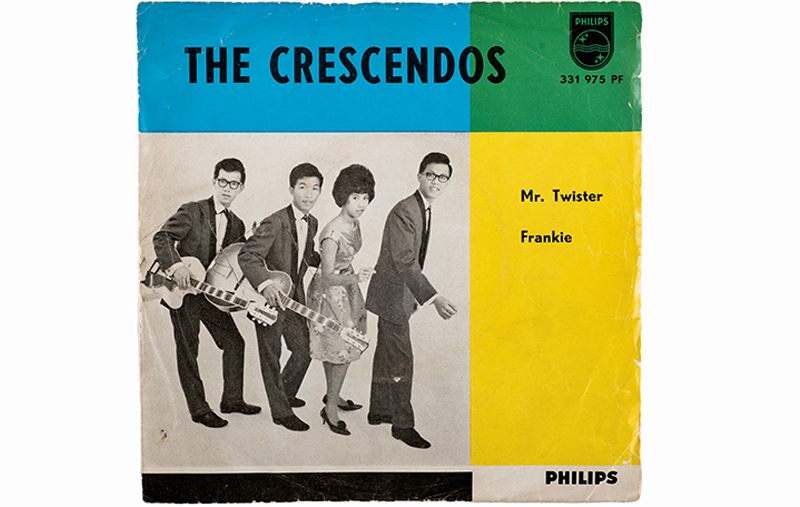

Budding musicians saw Talentime as a way of gaining visibility and kick-starting their careers. “During that time, there was only one English radio station,” recalled John Chee of The Crescendos. “So whoever it is would listen to that radio station would ultimately hear us because the disc jockeys at the time were also wanting to push local talent.”

The Crescendos themselves were catapulted into stardom after catching the eye of producer and compere Kingsley Morrando while participating in Talentime in 1962.15 Morrando talked Philips into recording the band’s debut single, Mr Twister/Frankie (1963),16 which became the first record by a Singapore pop band released by an international record company.

Another group that found fame via Talentime was The Tidbits – a trio comprising teenage schoolgirls Serene Wee, her sister Merlina Wee and their cousin Bernadette De Souza. They clinched the top prize in the vocal group category with their rendition of “I Believe” in 1968.17 The Tidbits went on to release a vinyl recording featuring four songs, “I Believe”, “Breaking Up Is Hard to Do”, “Never My Love” and “Lace Covered Window”,18 becoming Southeast Asia’s first recording artistes on RCA’s international label.19

While the early Radio Malaya versions of Talentime used an applause meter, by 1954, the contest began to rely on judges.20 And though it must have been nerve-racking being judged on stage, being a judge was no easy task either. Judges were also under the microscope for their verdicts. Following heated rounds of competition, complaint letters appeared in local newspaper forums like clockwork.

“This is not the first time I have considered the three judges to have erred but it is the first time they have failed to select two good entertainers. It has been announced that they judge solely on what they hear, and I am now inclined to agree, only it appears they give points on the APPLAUSE they hear and not the quality of the performers,” wrote W.A. Morton to the Straits Times in May 1962.21

It was critical for a talent competition to get its judging criteria right. Eleven days before the finals of the 1971 Talentime, a meeting involving the broadcaster and show judges was convened for this precise purpose. A glimpse of the meeting notes reveals the thinking of the Talentime organisers: “Some of the judges would concentrate on the visual and presentation aspects of the contestants, while the others pay more attention to the musicianship qualities – e.g. voice, musical interpretation, etc. The ration of the marks for presentation and showmanship should be around 30%, while 70% would go towards musicianship… During the transmission of the final, compere Kenneth Lim would make a specially prepared announcement explaining the way the contestants are being judged.”22

This fixation on adjudication could seem excessive at times. During the 1976 English Talentime final, the two emcees spent half of the 70-minutes programme tallying up the scores from individual judges in front of a live audience.23

I Want My MTV

The launch of television on 15 February 1963 in Singapore, and eventually a televised version of Talentime four years later, resulted in the show emphasising spectacle. Audiences in the age of television had more stringent expectations for singers – not only did their musical performances have to be up to mark, but their entire visual language had to impress – from costumes and movements, down to facial expressions.

In 1978, The Masquerades performed in skin-tight costumes, red capes and sequinned masks.24 The group continued their gimmick of appearing masked until the finals. “The revelation of their faces at the end of their song, I Want to Give Everything to You (including their identity) was an appropriate close to their performance,” reported the Straits Times. The Masquerades eventually took third place in the vocal groups category.25

Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, the airwaves were brought under the Ministry of Culture’s Department of Broadcasting. Public radio and television services were reorganised into a monolithic broadcasting entity, Radio and Television Singapore (RTS). Radio and television programmes were then used as critical tools in the government’s efforts to create a Singaporean cultural identity.

Government policy had an impact on the kinds of music that was deemed acceptable for Talentime. While musical genres such as psychedelic rock, metal and punk rock blossomed in North America and Western Europe between the 1960s and 1970s, RTS played it safe in compliance with the government’s anti-yellow culture campaign at the time.26

The government also sometimes intervened directly during the contest. During 1971’s Talentime, Johnny Tan tried his luck again. (He had made it to the finals of Radio Talentime in 1968.27)

Tan, apparently, was notable because of his campy stage persona. The New Nation reported that “[h]alf-way through the recording, the shocking, bell-bottomed Johnny Tan, who had TV viewers here in fits of laughter two years ago, makes an equally hip-swaying entry. Blowing kisses around the studio and swinging his arms wildly, he makes his declaration with This is My Song”.28 After watching one of Tan’s performances, Culture Minister Jek Yeun Thong issued an order that “[n]o contestant similar to Johnny Tan may be allowed to participate in subsequent heats”.29

The Winner Takes It All?

While everyone obviously wanted to win, being crowned rarely translated into professional success and many winners faded quickly into obscurity. The more fortunate ones include T.F. Tan, winner of the 1971 Talentime, and Sugiman Jahuri, first-prize winner in the English section of the 1973 Talentime, who went on to become household names.30 Tan, a tropical fish dealer whose powerful voice called to mind singers like Tony Bennett and Andy Williams, had won “more [T]alentime quests than any other amateur in Singapore”. One New Nation article claimed that “anyone old enough to remember the series remembers T.F”.31

Sugiman released a string of records, including I Look at You (Columbia; 1968), Kesah Chinta (Parlophone; 1971) and Woman Woman (Columbia; undated).32 Another notable winner was, of course, Jacintha Abisheganaden.

If winning didn’t automatically translate into commercial success, losing the competition did not spell failure either. Quite a few contestants who did not make the finals went on to have long, successful careers in music.33 These include Joe Chandran of the X’periment, Alban De’Souza34 and Talib Ismail of Tania, and Mel Ferdinands of Gypsy.35

Breaking Up Is Hard to Do

On 31 January 1980, RTS was dissolved and its functions were transferred to the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (SBC). SBC reprised the Talentime format “uneventfully” through to the 1980s.36

By 1988, SBC had articulated a new “entertainment concept” for the programme, which emphasised presentation and showmanship. “I want to do away with nervous contestants quaking on centrestage,” said producer Lim Sek. Under Lim, Talentime participants were accompanied by backup dancers. He also overturned the decades-old rule that barred professionals from participating.37 The era of Talentime as an amateur competition was no more.

Talentime was put on hiatus in the 1990s, as local broadcasting entities went through a process of privatisation to give broadcasters greater flexibility in order to compete with cable television and other foreign competitors.38 It was not until the new millennium that Mediacorp, the media conglomerate that succeeded SBC, launched Talentime 2001 in a bid to unearth local “pop stars”.39

The show, unfortunately, received scathing comments in the press after the first quarterfinals on 14 October 2001. “Talentime 2001 appears so far to be no more than a one-hour, glorified karaoke session, with prizes in place of the alcohol,” wrote Lionel Seah for the Straits Times. “[W]hat Talentime 2001 seems to be looking out for is a mediocre singer who looks fabulous and can do complex dance routines for the duration of one short song.”40

Talentime would soon seem like an anachronism when the British reality television singing competition Pop Idol debuted in October 2001 and eventually spawned an international Idols franchise. American Idol began airing in the US in June 2002 and was hugely popular in Singapore. Mediacorp replaced Talentime with its own Singapore Idol in 2004, incorporating confessionals and melodramatic interviews with contestants – it was a hit.

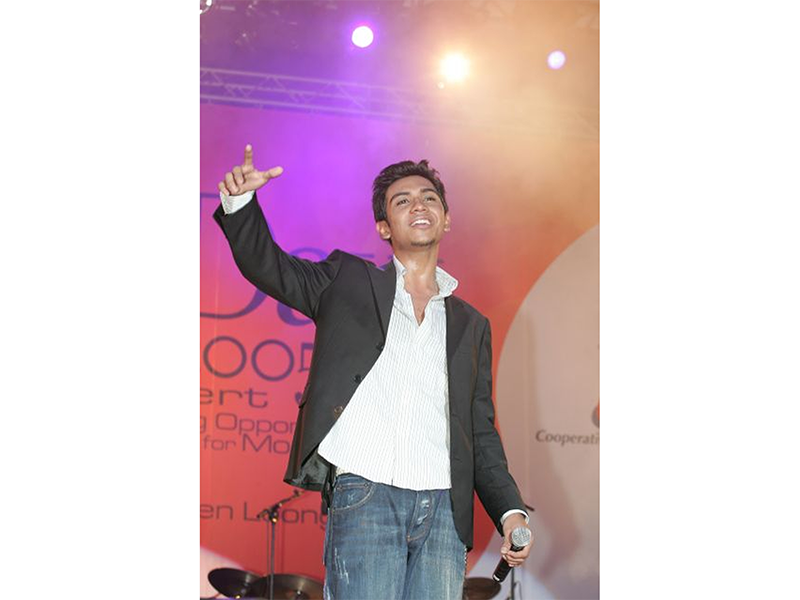

Auditions for Singapore Idol that began in June 2004 attracted more than “3,000 wannabe-stars to warble for a shot at fame and a recording contract”. In the finals on 1 December that year, 8,000 people turned up at the Singapore Indoor Stadium to watch Taufik Batisah emerge as the winner.

“Singapore Idol’s claim to fame is the fact that it managed to collectively rally Singaporeans from all walks of life to cheer, cry and hammer away at their mobile phones to vote for their favourite singer – not an American crooner or a British rapper, but a true-blue Singaporean soulster,” wrote Sujin Thomas of the Straits Times.41 Singapore Idol continued for two more seasons – in 2006 and 2009.

In recent years, reality television shows such as American Idol, America’s Got Talent, The X-Factor, The Voice and The Masked Singer have displaced traditional talent contests. Although these have probably sounded the death knell for Talentime in Singapore, the misty memories of the way we were will undoubtedly continue to light the corners of our minds.

Mark Wong is an Assistant Director/Senior Specialist (Oral History) with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore, where he leads the oral history project on Singapore’s experiences with COVID-19. He is a Council Member and Regional Representative (Asia) of the International Oral History Association.

Mark Wong is an Assistant Director/Senior Specialist (Oral History) with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore, where he leads the oral history project on Singapore’s experiences with COVID-19. He is a Council Member and Regional Representative (Asia) of the International Oral History Association. Jamie Lee is an Assistant Archivist with the Audio Visual Archives Department, National Archives of Singapore. A lifelong advocate of the moving image, she works to connect Singaporeans with their audiovisual heritage by curating records and their metadata. She is currently completing her Master’s in Library and Information Science specialising in Archival Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Jamie Lee is an Assistant Archivist with the Audio Visual Archives Department, National Archives of Singapore. A lifelong advocate of the moving image, she works to connect Singaporeans with their audiovisual heritage by curating records and their metadata. She is currently completing her Master’s in Library and Information Science specialising in Archival Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.NOTES

-

Vernon Cyril Palmer, oral history interview by Daniel Chew, 19 January 1994, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 12, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001423), 78. ↩

-

“Malayan Listeners State Their Fancy,” Straits Times, 5 January 1949, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Search for Local Talent,” Straits Times, 26 January 1949, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Radio Malaya Gives Unknown Artistes Chance To Be Heard,” Malaya Tribune, 25 January 1949, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Vernon Cyril Palmer, oral history interview, 19 January 1994, Reel/Disc 9 of 12, 78. ↩

-

“He Won Loudest Cheers,” Straits Times, 19 February 1949, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“S’pore Crooners Will Get the Air,” Straits Times, 20 February 1949, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“L. Fenton Wins ‘Talentime’,” Malaya Tribune, 28 April 1949, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Gate-Crashers Beware!” Sunday Tribune (Singapore), 5 June 1949, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Veteran Mimic Wins Talent Quest,” Straits Times, 13 February 1989,17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ross Laird, “From Keroncong to Xinyao: The Record Industry in Singapore, 1903–1985 (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2023), 154–56. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 338.4778149095957 LAI) ↩

-

Teo Lian Huay, “Remember When Talentime Was New?” Straits Times, 17 August 1982, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Reginald Verghese, oral history interview by Pat D’Rose, 5 July 1995, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 6, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001666), 31. ↩

-

Raymond Ho and John Chee, oral history interview by Joseph C. Pereira, 8 July 2007, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003163), 114–15. ↩

-

The Crescendos, “Mr Twister,” 1963, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2016000728) ↩

-

“First S’pore Recording Stars on American Label,” Straits Times, 2 June 1968, 12. (From NewspaperSG); Ministry of Culture, “Berita Singapura: 1. Sang Nila Utama Secondary School 2. Singing Trio,” 1960s, video, 00:09:41. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1982000239) ↩

-

The Tidbits, “I Believe,” 1968, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession nos. 2012003946 and 2014003894) ↩

-

“Praises for ‘Tidbits’,” Eastern Sun, 17 May 1968, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Crackerjacks Come Out Top in Talentime Finals,” Singapore Standard, 4 September 1954, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

W.A. Morton, “Judging Applause in Search for Talent,” Straits Times, 22 May 1962, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, “Meeting Held on Tuesday 7th December ‘71 at the Engineering Conference Room – Television Centre,” in Talentimes/Concerts (English), December 1968 to January 1977. (From National Archives of Singapore, record reference no. DDB 35), 188. ↩

-

Radio and Television Singapore, “RTS Talentime 1976 (Grand Final),” 1976, 1 inch B. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1997002767). [Also on mewatch] ↩

-

Radio and Television Singapore, “Talentime 1978 (Final),” 1978, 1 inch B. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1997002770). [Also on mewatch] ↩

-

Susie Soh, “Faridah and Cavarelle Top Talentime ’78 Finals,” Straits Times, 29 December 1978, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Seow Peck Ngiam, “Anti-Yellow Culture Campaign,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published September 2021. ↩

-

“Top S’pore Talent for Show,” Straits Times, 18 April 1968, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Edgar Koh, “Not a Laughing Matter…,” New Nation, 2 August 1971, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, Talentimes/Concerts (English), 202. ↩

-

“Talentime Winner Gives Prizes to Charity,” Straits Times, 19 December 1971, 1; Bailyne Sung, “It’s First Place for Sugiman,” Straits Times, 25 February 1973, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lu Lin Reutens, “Talentime Star’s Charity Dreams,” New Nation, 17 December 1974, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sugiman Jahuri, “I Look At You,” 1968, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2016002561); Sugiman Jahuri, “Kesah Chinta,” 1971, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2019020861 and 2019044217); Sugiman Jahuri, “Woman Woman,” undated, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2015014660) ↩

-

Margaret Cunico, “Talentime Springboard,” New Nation, 27 June 1979, 10–11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Alban De Souza and Mahani Mohd, “Mimpi Gembira,” 1973, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2015014470); Alban De Souza, “Ratapan Anka Tiri,” 1974, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2015014471); Alban De Souza and Mahani Mohd, “Jangan Bersedeh,” undated, vinyl disc. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2019020868) ↩

-

“In Person Ep 59: Gypsy,” 1983, video, 00:43:06. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1997005194) ↩

-

Juniper Foo, “Young, Hip and Faster Than Ever,” Straits Times, 16 October 1988, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Cherian George, “SBC Restructured into Several Govt-Owned Firms,” Straits Times, 1 October 1994, 29. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sophia Ang, “Pop Stars Wanted,” Today, 6 July 2001, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lionel Seah, “Talent Time for What?” Straits Times, 22 October 2001, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sujin Thomas, “Singapore Idolmania,” Straits Times, 25 December 2004, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩