Babas and Nonyas: The Peranakan Chinese in Singapore

The local Baba community has a social history that is as fascinating as their material culture is colourful. Known as Peranakan (or Peranakan Cina), the Babas are an acculturated community of Southern Chinese domiciled in the Straits Settlements since they first settled in Melaka in the 16th century.

Writings On the Babas

The local Baba community has a social history that is as fascinating as their material culture is colourful. Popularly referred to as the Peranakan (or Peranakan Cina - Malay for Chinese Peranakan1), the Babas are an acculturated community of Southern Chinese domiciled in the colonial Straits Settlements since they first settled in Malacca in the 16th century.2 Their long residence in the Malayan Peninsula saw the primarily Hokkien community adopting cultural elements from the Indonesians, Malays, Indians and colonial British, and developing a unique cultural tapestry seen in their use of Baba Malay language, nonya attire and cuisine. Yet, defining a Baba and his community remains a complex task both for the researcher and community member, as the community continues to adapt through difficult periods and different eras.

While ferreting through books in the National Library’s Singapore and Southeast Asian Collections, new-old materials were uncovered which could shed more light on the complex study of Baba identity. These books by the Babas and about the Babas serve as a window into the community, providing a peek into their lives, stories and values. With the publication of A Baba Bibliography, more than 1,500 annotated citations of books, chapters in books, magazine and newspaper articles, websites and audiovisual resources on the subject were brought together in a single publication. They span almost 200 years of writing, from the early 19th century to publications in the 21st century.

Most studies on the Babas focus on specific subjects such as literature and language, material culture, social history and identity. This bibliography, however, brings together these disparate subjects, spanning across popular perspectives and including obscure academic studies in the hope that new insights and a more integrative concept of the Babas can be articulated.

Stories From Long Ago

When discussing Baba writings, the traditional stories of the Babas, known in short as Chrita dahulu-kala, or “Stories of long ago”, published between the late 19th century and the early 20th century, come to mind. These publications are Baba Malay translations of Chinese classics, adventures and romance.

Studies of these publications often focus on their holdings in various libraries in Asia and the West. Salmon & Destenay’s (1977) Writings in Romanized Malay by the Chinese of Malaya was one of the earliest to detail the holdings of these titles in various libraries, including the British Library, the National Library in Singapore and the Dewan Bahasa Library in Kuala Lumpur. This was followed by an analysis by Tan (1981) and Proudfoot (1989, March), with added information on publishing histories. The most recent studies are by Yoong (2001, 2002, 2004), which besides reviewing holdings and publishing trends, has categorised the titles by types of stories and studied the persons behind the publications, including translators, illustrators and publishers.

Most studies indicate that the National Library in Singapore has less than 30 such titles, but the process of compiling this bibliography uncovered at least 44 distinct titles of these unique translations. Many were donated by Linda Lim through the National Museum in 1986. These have been microfilmed and are stored along with other purchased microfilm titles to provide access to a wider range of such titles.

The Chinese stories and why the Babas chose to translate is not generally the subject of analysis. Instead, the books are studied for the Baba Malay used. It is a vibrant mix of Baba Malay and Hokkien - unadulterated and not standardised, written as if to be read aloud. Peppered within the text are proper English translations and sometimes Chinese scripts, which attempt to clarify some aspects of the story.

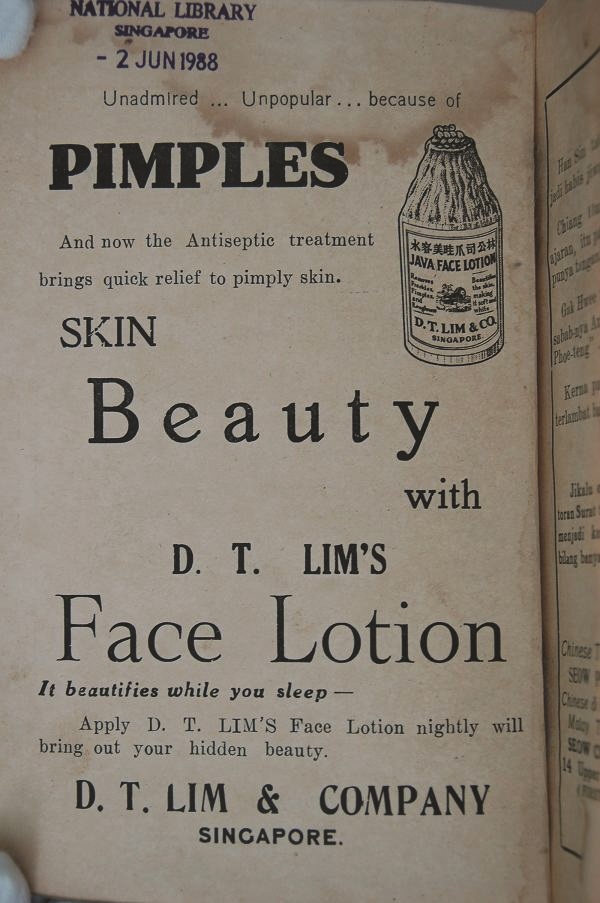

The translators, who often were the publishers, wrote short promotional introductions that told little about the story and more about the effort put in for production, principally that the price of $1 for the publication remained a reasonable fee in the light of the effort put into the translations. The advertisements and appended short essays in the well-thumbed paperbacks also speak of the social life of the community at the turn of the century. Publishers such as D. T. Lim were involved in sales of consumables such as face lotions, diabetic teas and sambal spices which they gamely advertised in their books.

Besides Chinese classics, the bibliography also covers articles which analyse these writings as well as Baba poetry (pantun and syair), Baba performance as seen in the Dondang Sayang, Wayang Peranakan, and dramas of the late 20th century and analysis of these. Language use and structure, wordlists and dictionaries, and general challenges in language acquisition are also listed.

Material Culture

In the 1980s, there was a revival of interest in the Baba community as older families sold off their family heirlooms and their material culture spilled into the open market, attracting the interest of discerning buyers and the curious.

Fuelled by this influx of material culture, museums began to focus on exhibitions solely on the Babas. In Singapore, the National Museum began with a showcase of domestic items, beadwork and jewellery of the Babas. Then in 1997, the Asian Civilisation Museum opened its first wing off Armenian Street, where a large part of the space was dedicated to displays of Baba material culture.

Philosophy lecturer, Ho Wing Meng, turned his hobby3 of collecting Straits Chinese material into four publications, published in the 1980s4, analysing the Baba material culture. The detailed photographs in these publications, as well as exhibition guides and auction brochures published around the same period, increased the interest in the material wealth of the Babas of the past. The pink-blue and yellow-green of nonya ware are reflected in similar colours in their kebaya and kasut manek.5 Singapore’s Peranakan Association saw younger members join, many seeking to savour the culinary fare of the true-blue Nonya or to acquire a set of kerosangs6 to accompany their new kebayas or develop a new hobby in kasut manek beadwork.

Even as recent as the 21 st century, the late Datin Seri Endon Mahmood’s patronage7 of the nonya kebaya encouraged a revival in the making and use of these delicately embroidered dresses, and led both Malaysians and Singaporeans to acquire these as their own local costumes.

Interestingly, although the hues and decorative details of things Baba seem so clearly defined today, there is limited information on a unique style that can be said as truly Baba. Whether it is architecture or jewellery, scholars do not seem to agree over a distinctly Straits Chinese style, although certain details may be construed as peculiar to the Babas. Even so, the mish-mash of styles reflecting the best of the Chinese, British or Malays as used by wealthy Straits Chinese have become acknowledged as typical of Baba taste and have today acquired a standing of high regard.

The bibliography attempts to capture all material aspects of the Baba, from architecture to interior furnishing, kitchenware and porcelain, silver and jewellery, attire and dress sense.

Social Life

The Baba community expresses its values through ritual practice and social interactions. Early studies of the community focus on descriptions of the early Chinese settlement in the coastal city of Malacca. Malaccan-born De Eredia (1613),8 a navigator and explorer, made some of the earliest observations of the community. However, it was later colonials and adventurers who captured the unique expressions and style of the Babas. Isabella Bird (Isabella Bishop) described the Anglo-Chinese and their peculiarities in some detail9 in her famed publication The Golden Chersonese, published in 1883. Vaughan had, as early as the 1850s, written notes on the Penang Chinese10 but it is his Manners and Customs of the Chinese, published in 1879, that provided a detailed analysis of the Straits Chinese. Victor Purcell, who had served in the Malayan Civil Service between 1921 and 1946, continued an in-depth description of the Chinese from the Occupation to the post-war period, based on research conducted in the 1930s.

After the war, the Straits Chinese British Associations of Singapore, Malacca and Penang voiced the struggles of the Babas in retaining their treasured British rights in the face of an increasing nationalistic fervour that sought to throw off colonial restraints. While individual Babas took on key political leadership posts in the fledgling nations of Singapore and Malaysia,11 the Baba community itself was being derided for its political apathy. Much of the struggle with its sense of political and nationalistic identity can be found in newspapers and magazine articles of the period.

Thereafter, while the notion of being Baba no longer carried political connotations, cultural aspects of Baba practices became more and more a subject of study in post-independent Singapore and Malaysia. These were found in publications of specific rituals such as wedding ceremonies12 and in autobiographies of the ordinary Baba, where descriptions of kinship ties and everyday rites showed the lifestyle of Babas in the past and their struggles through the Japanese Occupation.

In the 1980s, several ethnographic studies and landmark publications on the social practices of the Baba were published. John Clammer (1980) looked at the community from a sociological perspective, providing an academic analysis of ethnicity and its expression.13 On the other hand, Felix Chia’s (1980) publication in the same year described the Baba from within the community, giving anecdotal accounts, personal reflections and insiders’ notes over and above a researched background to the community.14 Soon after, Tan Chee-Beng (1988)15 provided a detailed ethnographic study of Malaccan Babas, capturing ritualistic practices as well as social customs and interactions, thus giving flesh to the actual workings of the community. With Rudolph’s (1994) publication,16 the Babas were described based on how they were perceived and how they perceived themselves through distinct time periods. Social identity was not defined merely by ritual practices or material culture but also by the community’s political and nationalistic affiliations.

The Baba community gained a new dimensionality as they were studied within the context of their time, complementing specific studies of rituals and aspects of the community. The beautifully illustrated and well-researched tome by Khoo Joo Ee (1996) The Straits Chinese: A Cultural History is such an example: it captures both the intricacies of the material culture as well as the issues of social identity among the Babas of Penang.

Both the broad study of the Baba community and the specific papers on ritualistic aspects of Baba culture are listed in the bibliography. Added to these are area studies of the Babas in Singapore, Penang and Malacca and broader studies of Babas. The latter compares the Babas to the acculturated Chinese in Southeast Asia and the related acculturated non-Chinese such as the Chetty Melaka, the Adjarns of Phuket and the Peranakan-like Chinese in Kelantan and Terengganu.

Future Writings on the Babas

The lines between social and material culture, physical and spiritual space, past and present, are seldom static. Thus, as the community evolves and questions of identity continue to be raised, it is hoped that A Baba Bibliography may serve as a resource to nurture new interpretations of what makes a Baba.

More importantly, through the publication of A Baba Bibliography, it was found that many unique resources on the Babas were not available in the National Library of Singapore. Patrons of the Baba community are thus encouraged to donate their own wealth of resources to the National Library so that a wider community can glean from the treasures of their forefathers and the generation of today can appreciate afresh the wisdom of the past.

NOTES

-

Various scholars and Baba authors have made a distinction between the terms Straits Chinese, Straits-born Chinese, Peranakan Chinese and Baba. In fact, technically, the term Baba refers to the men within the community and Nonya refers to the women. Jeurgen Rudolph, Reconstructing Identities: A Social History of the Babas in Singapore (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 RUD), however, notes that in the pre-war Straits Settlements, such distinction of terms were not always implied and the names were often used interchangeably for the Baba community. For the sake of simplicity, the community is referred to as Baba in this essay. ↩

-

Early Chinese records indicate that Chinese settlements were in Malacca much earlier but the beginnings of an acculturated Chinese community is often traced from the 16th century. ↩

-

John de Souza, “Scholar, Writer, Collector,” Straits Times, 11 June 1984, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

At least three of his publications were published in the 1980s while the fourth was published in the 1990s – Ho Wing Meng, Straits Chinese Porcelain: A Collector’s Guide (Singapore: Times Books International, 1983) (Call no. RSING 738.209595 HO); Ho Wing Meng, Straits Chinese Silver: A Collector’s Guide (Singapore: Times Books International, 1984) (Call no. RSING 739.237595 HO); Ho Wing Meng, Straits Chinese Beadwork & Embroidery: A Collector’s Guide (Singapore: Times Books International, 1987) (Call no. RSING 746.509595 HO); Ho Wing Meng, Straits Chinese Furniture: A Collector’s Guide (Singapore: Times Books International, 1994) (Call no. RSING 749.295957 HO) ↩

-

Kebaya - the full dress comprises a blouse and a sarong skirt. The intricately embroidered blouses of the nonya, through the technique known as sulam, would have delicate holes enhancing the designs of flowers, peacocks and other aspects of nature. Kasut manek - the beaded slippers were made of manek potong. The beads had cut sides that added to the glitter in the design of flowers and nature. ↩

-

Kerosangs - often in a set of three and made of gold, set with cut diamonds, the Kerosang acted as brooch-like buttons for the baju kebaya or the blouse of the kebaya. ↩

-

Datin Seri Endon Mahmood published two books on the Nonya kebaya, namely The Nyonya Kebaya: A Showcase of Nyonya Kebayas From the Collection of Datin Seri Endon Mahmood (Kuala Lumpur: The Writers’ Pub. House Sdn Bhd, 2002) (Call no. RSEA q746.92 NYO) and Endon Mahmood, The Nyonya Kebaya: A Century of Straits Chinese Costume (Singapore: Periplus, 2004). (Call no. RSING q391.209595 END). Her collection was also exhibited in both Malaysia and Singapore museums, attracting a large following. ↩

-

The J. V. Mills translated the Portuguese publication into English in the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1930, J. V. Mills, Eredia’s Description of Malacca, Meridonial India and Cathay, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 8, no. 1 (109) (April 1930): 1–288. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Bird Isabella, The Golden Chersonese: The Malayan Travels of a Victorian Lady (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1990). (Call no. RSING 959.5 BIS) ↩

-

Jonas Daniel Vaughan, “Notes on the Chinese of Pinang,” The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 8 (1854): 1–27. (Call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU; microfilm NL1891) ↩

-

In Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew and Goh Keng Swee were some individual Babas who took on the mantle of political leadership while in Malaysia, the Malaccan Baba Tan Cheng Lock and thereafter his son, Tan Siew Sin, reigned as heads of the Chinese political party and as Finance Ministers. ↩

-

Cheo Kim Ban, A Baba Wedding (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1983). (Call no. RDLKL 392.5 CHE). This was just one of many articles and publications on the elaborate Baba wedding. ↩

-

John R. Clammer, Straits Chinese Society: Studies in the Sociology of Baba Communities of Malaysia and Singapore (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1980). (Call no. RSING 301.45195105957 CLA) ↩

-

Felix Chia, The Babas (Singapore: Times Books International, 1980) (Call no. RSING 301.45195105957 CHI); Felix Chia, Ala Sayang! (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1983) (Call no. RDLKL 301.45195105957 CHI); Felix Chia, The Babas Revisited (Singapore: Heinemann Asia, 1994). (Call no. RSING 309.895105957 CHI) ↩

-

Tan Chee Beng, The Baba of Melaka: Culture and Identity of a Chinese Peranakan Community in Malaysia (Selangor: Pelanduk. Publications, 1988). (Call no. RSEA 305.89510595118 TAN) ↩

-

Rudolph, Reconstructing Identities. ↩