Singapore’s Hippie Hysteria and the Ban on Long Hair

Hippie culture was seen as a risk to Singaporean society in the 1960s and 1970s, and efforts made to reduce its influence eventually led to a campaign against men with long hair.

By Andrea Kee

In an interview in September 1970, just five years after Singapore became independent, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was asked about the problems Singapore had to resolve in the near future. Unsurprisingly, he identified economic viability as the first task that the young nation had to address. What was surprising, however, was what he identified as the next most pressing problem facing Singapore.

“The second point is the problem of being exposed to deleterious influences, particularly from the ‘hippie’ culture which is spreading across the jet routes,” he said. “We are a very exposed society, having both an important air and sea junction, and the insidious penetration of songs, TV, skits, films, magazines all tending towards escapism and the taking of drugs, is a very dangerous threat to our young. We will have to be not only very firm in damping or wiping out such limitation, but also to try and inoculate our young people against such tendencies. It is a malady which has afflicted several of the big capitals in the West and would destroy us if it got a grip on Singapore.”1

Hippie culture had reached Singapore’s shores by the late 1960s. Hippies represented a countercultural movement and were associated with a particular lifestyle. The fashion was loose, flowy garments, and psychedelic colours and images were common. The fashion for men was long hair and beards. Hippies were sometimes known as flower children because of the association of flowers with the movement. The regular use of recreational drugs such as marijuana and LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) was also seen as part of the lifestyle.

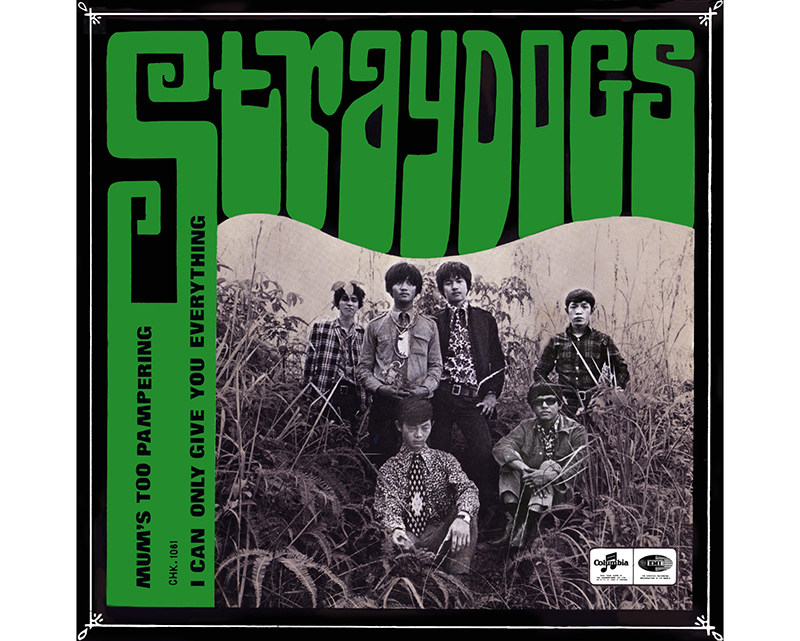

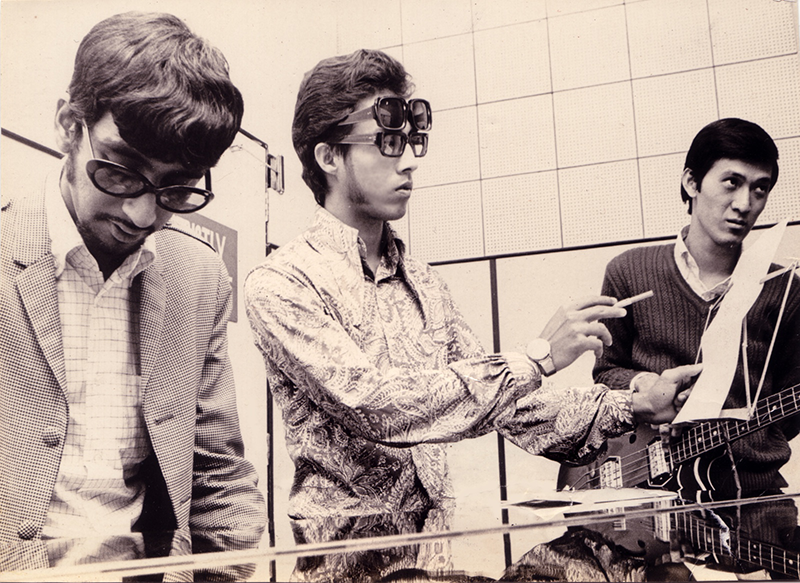

The culture spread through, among other things, music, and local bands in Singapore soon began to show signs that the movement was taking hold in Singapore. In April 1968, the local band The Straydogs performed at a show titled Purple Velvet Vaudeville at the National Theatre, an event that the Eastern Sun dubbed “the big Hippie show”. The paper reported that the stage and auditorium were “decked up with flowers and other psychedelic decorations”.2

“My sister dressed me up with a lot of flowers and sewed bulbs all over me,” recalled Dennis Lim, the band’s bass guitarist. “So, when the intro [started], I stepped on the switch, and I was all lighted up.”3 Lim also sported long hair that he had grown since his school days in anticipation of becoming a musician.4

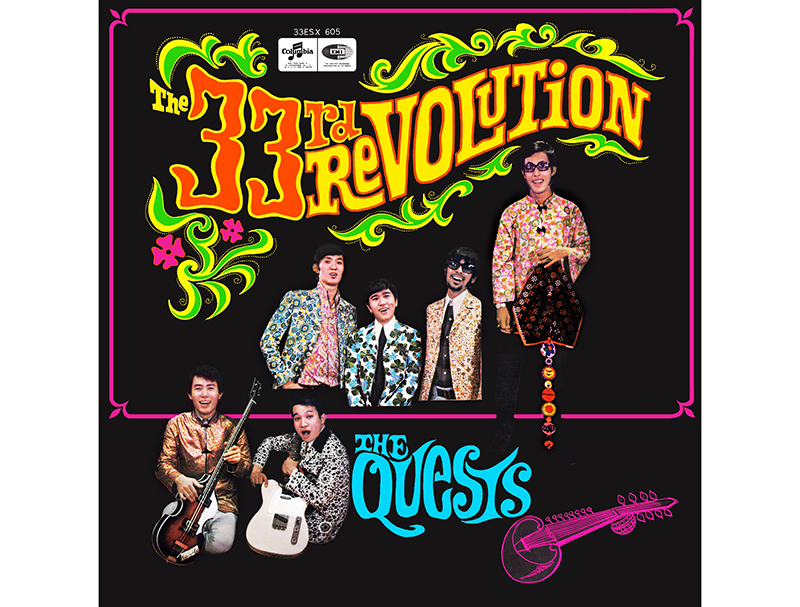

The Straydogs weren’t the only local band to embrace the movement. “We followed the flower [power], and we made flower coats,” recalled Sam Toh, who played bass guitar for The Quests. “And Vernon [Cornelius] has got a lot of ideas. And he was wearing flower things. We are all flower people.”5

In September 1968, the Straits Times reported that there were approximately 50 “Flower People” in Singapore sitting outside shopping centres and cinemas strumming their guitars and making chalk drawings on the pavements.6

Drugs and the Hippie

Wearing flowers, strumming guitars and making chalk drawings were not necessarily a problem. Consuming illegal drugs, however, was a different story. In the late 1960s, the drugs of choice were Mandrax (MX) sedative pills and marijuana (also known as cannabis or ganja). The users were mainly young people who visited discotheques and nightclubs. However, what concerned law enforcement the most was the increasing number of students taking drugs.7

In November 1971, the government set up the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) to deal specifically with drugs in Singapore. “The spread of [MX pill abuse among students] was due to the influence of the hippie culture from the West,” recalled Poh Geok Ek, Chief Narcotics Officer with the CNB.8

Former CNB narcotics officers Sahul Hamid and Lee Cheng Kiat remember working on several drug cases involving people they identified as hippies in the 1970s. One of these was a “hippie garden” at the junction of Paya Lebar and Geylang Road, which hosted nightly gatherings attended by kampong residents who were using cannabis supplied by a “big time ganja trafficker”. Despite numerous raids, the “hippie garden” continued being a favoured haunt, until the main drug supplier was nabbed.9

Because of the strong association between the hippie movement (including music) and illegal drugs, in 1970, the Ministry of Culture set up a team to “scrutinise all records which are suspected of disseminating ‘drug tunes’ through popular folk and [W]estern hit songs”.10

By April 1971, a total of 19 Western pop records had been classified as “detained publications” under the Undesirable Publications Ordinance due to their “objectionable” lyrics that supposedly made references to drugs. These songs were not allowed to be sold or performed in public and included The Beatles’ “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”. The only record that was officially banned was the soundtrack for the Broadway rock-musical, Hair, which had to be surrendered to the government or be destroyed.11

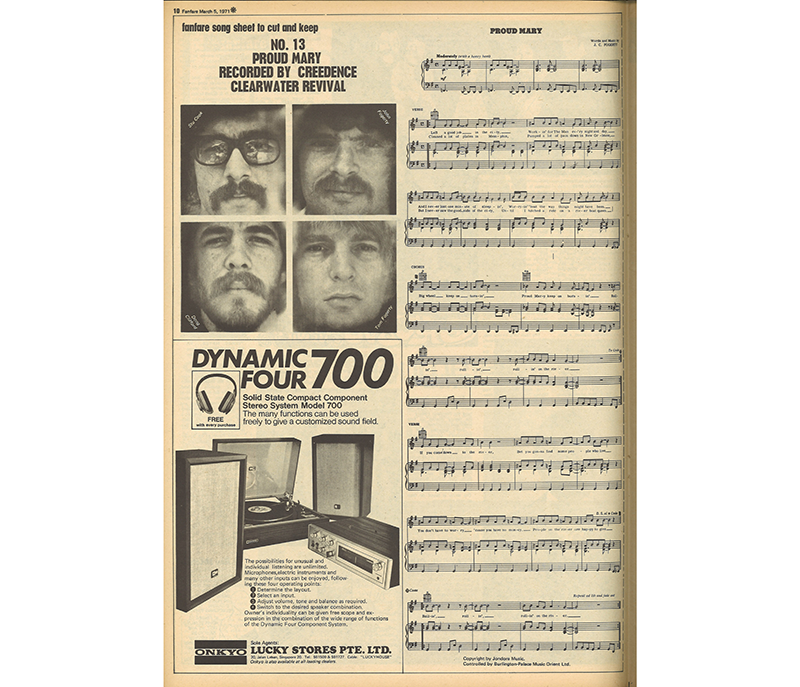

The government’s decisions were not always easily understood. One of the songs that made it to the list of “detained publications” was “Proud Mary” by Creedence Clearwater Revival. In March 1971, the Culture Ministry actually instructed the Straits Times Group to remove a page from an issue of the magazine Fanfare because it contained the lyrics of “Proud Mary”. As the New Nation newspaper noted in its report, “The words of ‘Proud Mary’ appear to refer to an American river ferryboat and the generosity of the people who live on the banks of the river. It does not seem… to contain any references to drugs”.12

Banning Hippies

As part of its anti-hippie efforts, in April 1970, Singapore banned foreigners who resembled hippies from entering Singapore. “Anybody who looks [like] a hippie has got to satisfy the immigration officers that he in fact is not, and that his stay in Singapore will not increase the ‘pollution’ to the social environment,” read the short statement from the Immigration Department.13 “The Immigration Department takes the stand that dirty and untidy-looking people with long, unkempt hair and beard are presumed to be hippies unless proved otherwise,” L.P. Rodrigo, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Home Affairs, told Parliament in 1971.14

“Long-haired, unshaven visitors”, like American students Gordon Burry and Klaus Kilor, were turned away by Singapore immigration officers at the Causeway due to their long hair, beards and floral shirts. “Both of us made a beeline for the barber’s [in Johor Bahru] immediately. Klaus did not need a haircut, but he had his moustache shaved off. I had my shoulder-length hair cut,” recounted Gordon. “We then went to a nearby laundry where I had a good blue suit of mine pressed. Klaus didn’t have a suit, but I loaned him a clean white shirt and tie. We then rented a chauffeured car and made a second bid at entering the city. This time, the guard smiled broadly at us and waved us on, after looking into the car for a brief second.”15

The subjective nature of who looked like a hippie led to inconsistent treatment. School teacher Andrew Jones and motoring instructor Trevor Roberts, both from London, were granted a special pass for a five‑day stay when they first arrived in Singapore. But Jones’ later request to extend his stay was rejected by immigration. He told the Straits Times: “We believe that many travellers like us are being mistaken as hippies and are asked to leave Singapore after a short stay. There should be some sort of a system to differentiate those who are hippies and those who are not. I have a beard but that does not make me a hippie. I personally do not believe in their philosophy and way of life.”16

Besides screening for hippies at checkpoints, immigration and police officers also raided red‑light districts on Sam Leong Road and Kitchener Road to track down “undesirable” foreign hippies living in Singapore who were known to take drugs and frequent those areas. Between 6 and 18 April 1970, 28 hippies were successfully rounded up and deported.17

The government defended the ban as necessary for Singapore’s survival. Defence Minister Lim Kim San said that Singapore could not risk adopting hippie culture due to its “degenerating and weakening” influence while Minister for Social Affairs Othman Wok said that “[w]hilst some may consider the policy adopted by the government in this regard as harsh and stern, it is inevitable if we have to protect what we have and improve on it”.18

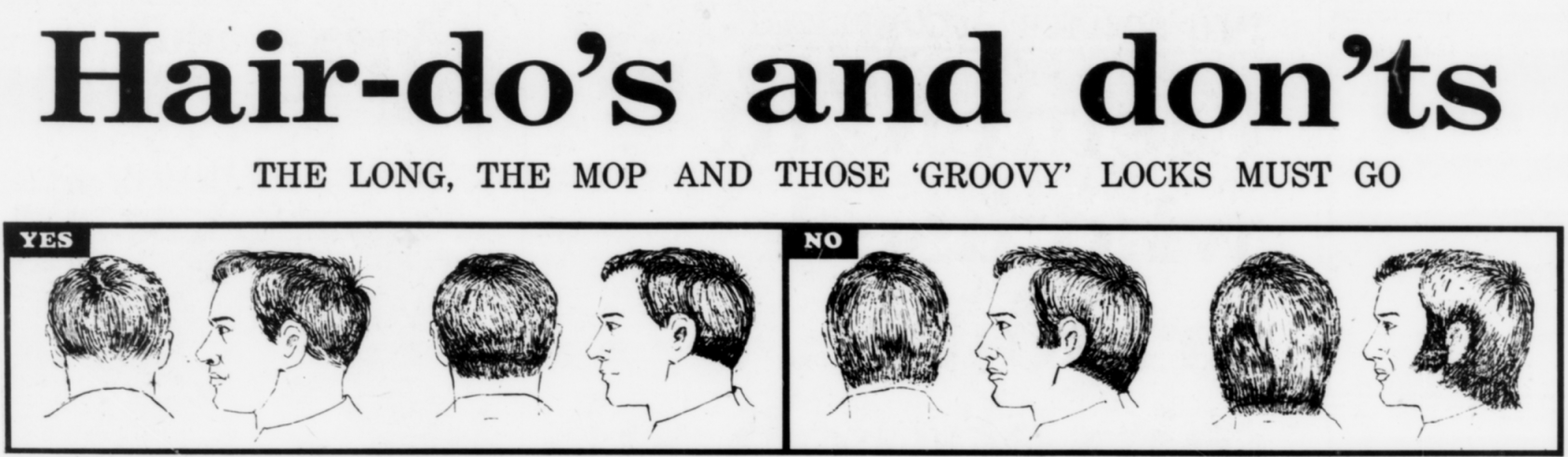

In addition to stopping so-called hippies from entering Singapore, the government also began to clamp down on local manifestations of the movement. In June 1970, long-haired male performers were banned from appearing on all locally recorded television programmes.19 The police also conducted surprise raids in areas frequented by youth. Their goal was to round up boys with long hair, bring them to police stations, photograph their hair and advise them to get haircuts. “Hippie dress and long hair are outward manifestations of a state of mind that may lead a person eventually to being hooked on drugs,” said Minister for Home Affairs Wong Lin Ken.20

Operation Snip Snip

The campaign against long hair on men shifted up a gear when the Ministry of Home Affairs launched Operation Snip Snip in January 1972. Immigration rules were tightened to refuse entry to all long-haired men unless they got haircuts. Those exempted were visitors invited by the government or “respectable organisations” for official business.21

One of the “victims” stopped at the Woodlands checkpoint was Malaysian businessman Frankie Tan who wanted to visit his wife before she gave birth. “I was really surprised and shocked by this sudden crackdown. I used to travel between Century Gardens housing estate in Johore Bahru and Singapore quite often. But this is the first time I have experienced such an embarrassing situation. Fortunately, my colleagues and I had enough money for a crop,” he told the Straits Times.22

Singaporean males with long hair were permitted entry, but they had to surrender their passports and could only collect them at the Immigration Headquarters the following day after getting their hair trimmed. While travellers were inconvenienced, barbers like M. Kandasamy near the checkpoint enjoyed a boom. “In my 20 years as a barber, I have never had such business. I closed shop at 10.30 pm yesterday instead of 8 pm as usual,” he said. Kandasamy also charged 30 cents more per cut instead of the usual $1.20.23

Musicians, who typically wore their hair long, bore the brunt of the campaign. The police visited nightclubs to advise long-haired musicians to trim their hair. While local musicians were willing to toe the line, some foreign performers were not as amenable, and cancelled their shows or stopped signing contracts with Singapore’s hotels and nightclubs altogether.24

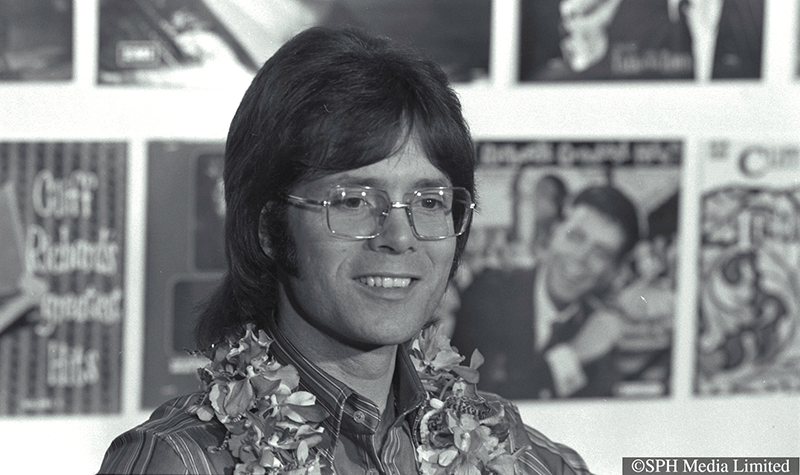

In August 1972, British pop singer Cliff Richard cancelled all three of his September concerts at the National Theatre, leaving fans disappointed. Richard and his band members had refused to cut their long hair, and it was believed that their applications for a professional visit pass was rejected by the Singapore authorities.25

Other top rock and pop groups, including The Who, Bee Gees, Cat Stevens, Tom Jones, Joe Cocker and the Chris Stainton Band, as well as Rick Nelson and the Stone Canyon Band, also scrapped their plans to perform in Singapore. Nelson’s promoter explained that they were passing over Singapore due to the “no-long-hair policy”, while other promoters were afraid that “any application made to the Immigration Department would be turned down” due to the long-hair policy.26

Not Serving and Hiring: Men with Long Hair

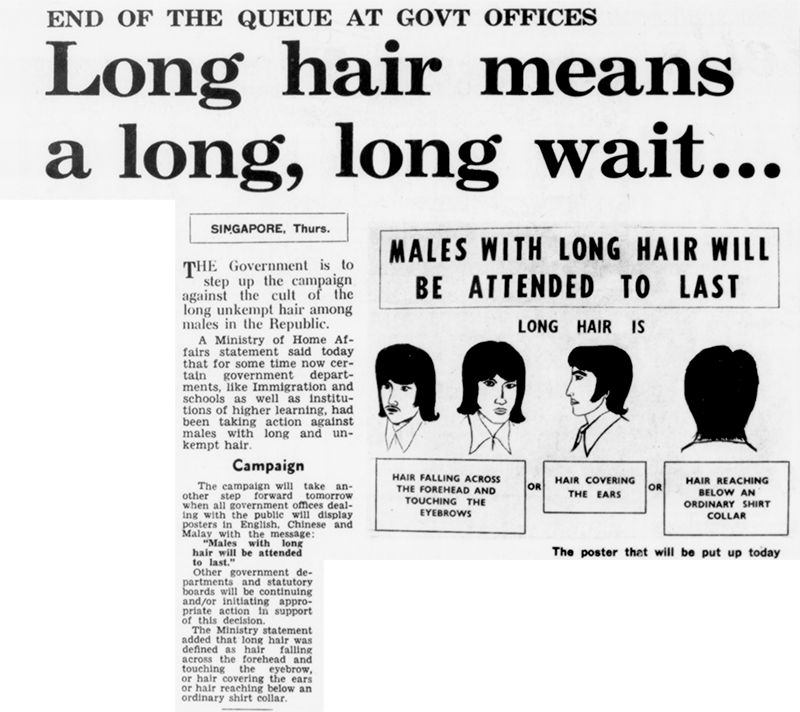

A few months after the start of Operation Snip Snip, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced that men with long hair would be served last at all government offices. Posters in English, Chinese and Malay with the message, “Males with long hair will be attended to last”, were displayed in government offices. Eventually, private-sector companies were also given these posters.27

The government also discouraged employers from hiring long-haired men. In July 1973, the Economic Development Board sent out a circular to the Singapore Manufacturers’ Association to inform that “the government strongly disapproved the appointment of long-haired male employees”.28

Civil servants were warned that those who defied the hair rules would face disciplinary actions, including termination of service. Those in the private sector were not exempt from the rules as names of male workers who continued wearing their hair long despite warnings were shared with the government for “appropriate action” to be taken.29

Schools also held regular “hair inspections”, and boys with long hair who refused to comply with warnings were given haircuts immediately. The lucky ones got their hair professionally cut by a barber hired by the school, while the unfortunate ones received a haircut from a teacher or the principal.30 However, the savvy ones would find ways to avoid detection. “Every time before I go to school, I would bundle my [long] hair and clip [it up] so it looked short,” said Dennis Lim of The Straydogs.31

Predictably, not everyone were fans of Operation Snip Snip. On 18 January 1972, a group of University of Singapore undergraduates staged a protest and told reporters that “the campaign against long hair is an infringement of our individual rights”. They marched around campus carrying posters and placards, some of which read, “When your hair is long, your rights are short”.32

Regardless, supportive letters appeared in the local newspapers. “My thanks go to the government for its campaign against drug-taking and long hair,” wrote a letter writer to the New Nation. “If prompt action was not taken earlier to check hippism, drug abuse and long hair, I believe our country by this time would have seen teenagers in shabby clothes with long hair and perhaps with drugs in their pockets, walking all over the clean and green island of Singapore.”33

Other Consequences

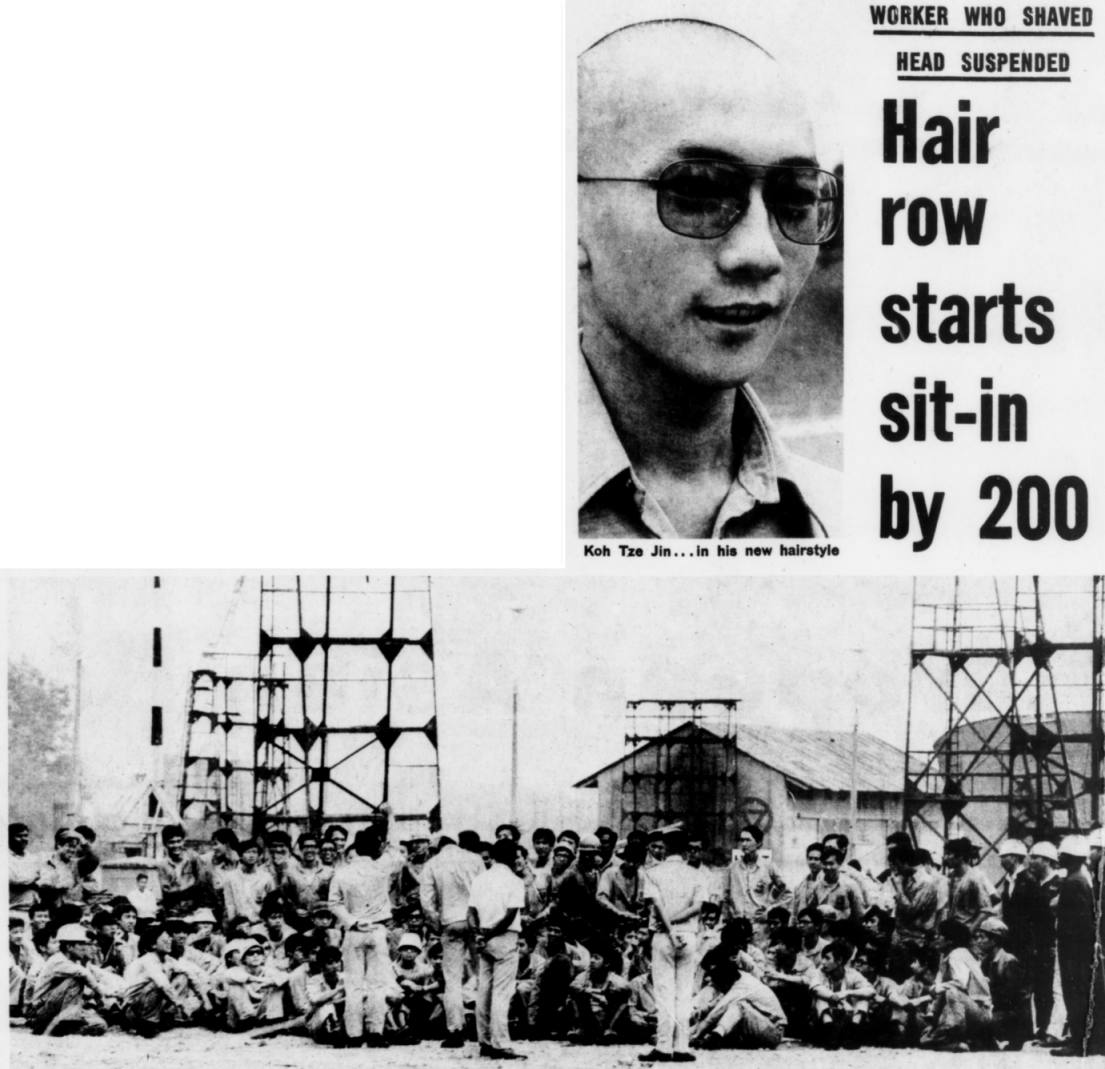

The campaign against long hair led to unexpected consequences. In November 1972, some 200 apprentices from Sembawang Shipyard staged a sit-in during their lunch hour to protest fellow shipwright apprentice Koh Tze Jin’s hair-related seven-day suspension. Earlier that week, he had received a one-day suspension for refusing to get a haircut as he felt that his hair was well above his collar. In response, he shaved his head bald. Koh told reporters that he did so “to avoid any further arguments with the company”. Unfortunately, his bosses saw his shaved head as an act of protest and suspended him for seven days, igniting the sit-in.34

It even led to a minor international incident with Malaysia in August 1970. Three Malaysian youths were caught up in an anti-long hair raid in Orchard Road and detained by Singapore police. They later accused the police of mistreating them and forcing them to get haircuts. Although the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) investigators who detained them stated in an internal report that the youths had agreed to the haircut, the damage was already done.35

Students from the University of Malaya protested the incident at the High Commission in Kuala Lumpur, prompting Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew to postpone a planned visit with Tunku Abdul Rahman. Reports stated that the postponement was “mainly to avoid embarrassing both governments”. As a result of this incident, Singapore issued an apology to the Malaysian government and all hair-cutting by the CID ceased.36

Changing Trends

By the end of the 1970s, there were fewer reports in the press about the crackdown on long-haired men. In March 1986, Lee Siew Hua of the Straits Times reported that “the long-hair-last signs have virtually disappeared even though officials maintain that the policy is very much alive”.37 Part of the reason for the easing up of long hair in the 1980s was simply due to changing trends. Hippies and hippie culture had long fallen out of fashion by then.

The government also lifted restrictions on music previously banned for being associated with hippies. In May 1993, the Ministry of Information lifted its ban on a number of songs, including Beatles classics like “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”, “With a Little Help from My Friends” and “Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. Fans of Bob Dylan were delighted that “Mr Tamborine Man” could finally play a song for them. Another song that got the green light, none too soon, was Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Proud Mary”.38

Looking back, it might seem odd that the government would want to regulate men’s hair styles back in the 1960s and 70s. Perhaps the most eloquent explanation comes from Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam who said in 1972 that the government “was not concerned whether men have long hair, short hair or no hair at all. It is not so stupid as to believe that the future of Singapore will be determined by the length of the dead cells its citizens sprout”. It was, he explained, “hippieism not hair style we are attacking” and added that the government did not believe that “hippieism can be eradicated simply by shearing locks”. What the government hoped was that by focusing and attacking long hair, “one of the symbols to which hippies attach great importance, we would be deterring many young people who are just being fashionable from being drawn into what is basically an obscene and pernicious lifestyle”.39

Hippies and hippie culture have become a footnote in history. These days, it is not uncommon for men to have long hair, though the fashion is for those tresses to be tied up in a ponytail or tucked into a man bun. A man sporting long shaggy locks is more likely to be a fan of an 80s bands like Bon Jovi or Guns N’ Roses than a wannabe hippie. The times, indeed, have been a-changing.

Andrea Kee is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development, as well as providing reference and research services.

Andrea Kee is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development, as well as providing reference and research services.Notes

-

Ministry of Culture, “Transcript of Press Interview Given by the Prime Minister, Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, at Sochi on 18th September, 1970,” speech, Sochi, Soviet Union, 18 September 1970, transcript. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. lky19700918) ↩

-

“The Big Hippie Show Today,” Eastern Sun, 19 April 1968, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Wee Kiang, oral history interview by Mark Wong, 24 November 2011, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 5, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003502), 101. ↩

-

Lim Wee Kiang, oral history interview by Mark Wong, 15 April 2010, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 5, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003502), 39. ↩

-

Lim Wee Guan and Sam Toh Hong Seng, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 10 July 2007, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 2, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003195), 56. ↩

-

Yap Chin Tong, “Unruffled Hippie ‘Prince’ Puffs Away As He Draws for a Living…,” Straits Times, 26 September 1968, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Council Against Drug Abuse (Singapore), Towards a Drug Free Singapore: Strategies, Policies and Programmes Against Drugs (Singapore: National Council Against Drug Abuse, 1998), 9. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 362.293095957 TOW) ↩

-

National Council Against Drug Abuse (Singapore), Towards a Drug Free Singapore, 10; Central Narcotics Bureau, Dare to Strike: 25 Years of the Central Narcotics Bureau (Singapore: The Bureau, 1996), 23. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 353.37095957 SIN) ↩

-

Central Narcotics Bureau, Dare to Strike, 36–37. ↩

-

“‘Drug’ Discs Pick Up New Listeners in S’pore,” Straits Times, 5 July 1970, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Keeping the Records Straight…,” New Nation, 7 April 1971, 7; ‘Drug Discs’ Under Study by Top Govt Team,” Straits Times, 14 March 1970, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Censor Takes Fanfare Page,” New Nation, 5 March 1971, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“S’pore Bans Hippies,” Straits Times, 10 April 1970, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Foreign Hippies (Banning of Entry into Singapore), vol. 30 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 8 March 1971, cols. 547–548, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=009_19710308_S0005_T0009. ↩

-

Maureen Peters, “Clip, Clip, Clip Way to Get Round the Causeway Clamp on Hippie Types…,” Straits Times, 11 April 1970, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

David Gan, “All Bearded Visitors Not Hippies, They Say,” Straits Times, 12 April 1970, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Unwanted Hippies on the ‘Wanted’ List,” Straits Times, 18 April 1970, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Govt Says It Again: No Hippies,” Straits Times, 5 June 1970, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“TV S’pore Bans Long Haired Artistes,” Straits Times, 10 June 1970, 27. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Edward Liu, “Long Hair Youths Vanish from the Streets,” Straits Times, 2 October 1971, 30. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

N.G. Kutty, “Flexible Policy in Long-Hair Clamps,” Straits Times, 11 January 1972, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

N.G. Kutty, “Op Snip Snip at the Causeway,” Straits Times, 10 January 1972, 26. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Kutty, “Op Snip Snip at the Causeway”; Kutty, “Flexible Policy in Long-Hair Clamps.” ↩

-

Gerry de Silva, “At Last Local Pop Groups Get a Chance at Top Billing,” Straits Times, 29 January 1972, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gerry de Silva, “Cliff Kept His Locks, But EMI Lost $10,000,” Straits Times, 22 August 1972, 15; Peter Ong, “Why Cliff Will Not Come to Singapore,” New Nation, 19 August 1972, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Long-Hair Ban Keeps Pop Stars Out,” New Nation, 29 August 1972, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Long Hair Means a Long, Long Wait…,” Straits Times, 23 June 1972, 8; Irene Ngoo, “5,700 Longhaired Men Warned,” Straits Times, 11 December 1974, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Govt to Bosses: Don’t Employ the Long-Haired,” Straits Times, 17 July 1973, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Govt to Bosses: Don’t Employ the Long-Haired”; Ngoo, “5,700 Longhaired Men Warned,” Straits Times, 11 December 1974, 15. ↩

-

“Now It’s Snip, Snip Time in the Schools,” Straits Times, 12 January 1972, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Wee Kiang, oral history interview by Mark Wong, 15 April 2010, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 5, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003502), 39. ↩

-

“Student Protest Over Snip Snip,” New Nation, 18 January 1972, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Spoken Word, “Hitting at Long-Hair,” New Nation, 22 January 1972, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Suan Kooi, “Hair Row Starts Sit-In by 200,” Straits Times, 16 November 1972, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Call for ‘Strong Protest’ to S’pore by Tun Ismail,” Straits Times, 19 August 1970, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lee Puts Off Visit,” Straits Times, 20 August 1970, 1; Philip Khoo, “Police Stop Snipping of Hippie Hair,” Straits Times, 3 September 1970, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Siew Hua, “Less Ado About Men With Long Hair,” Straits Times, 9 March 1986, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Siti Rohanah Koid, “Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!,” The New Paper, 26 May 1993, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sorting the Shaggy Sheep from the Hippie Goats,” New Nation, 31 January 1972, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩