A Plethora of Tongues: Multilingualism in 1950s Malayan Writing

From the melting pot of cultures and languages in postwar Singapore emerged the search for a Malayan identity, negotiated and presented through the lens of multilingualism in Malayan literature.

By Lee Tong King

The 1950s were a decade of flux for Malaya. In the aftermath of the Japanese Occupation and prior to political independence from colonial rule, Malaya, including Singapore, was embroiled in the rise of anti-colonial sentiment and British suppression of communist insurgencies, culminating in the Malayan Emergency of 1948. While these intervening years were rife with ideological struggle and armed conflict, they also incubated the beginnings of a distinctive Malayan literature – for instance as seen through the incorporation of local vernacular into written works – thereby opening the doors to a vibrant tradition of creative writing in the region.

Uniqueness of Malayan Chinese Literature

Since the early 1950s, Chinese fiction writers in Malaya became more experimental with their language medium, which was a standard written Chinese, based on the Mandarin vernacular, or bai hua, hailing from the 1919 May Fourth Movement in China. The backdrop to such experimentation was a polemic, sometimes dubbed the Great Debate, that occurred between December 1947 and April 1948. This took the form of a “paper war” across the literary supplements of several major Chinese newspapers of the time, such as Sin Chew Jit Poh, Nan Chiau Jit Pao, and Min Sheng Pau.

There were two camps, the Malayan-Chinese Literature School and the Overseas-Chinese Literature School,1 that expressed opposing stances around the contentious idea of the “uniqueness of Malayan Chinese literature”. The first group believed that the Chinese literature of Malaya should be distinct from China’s, as each had developed under very different sociopolitical circumstances. The latter group, comprising the so-called “immigrant writers” (writers from China who sojourned in Malaya), sometimes derogatorily called “refugee writers”, insisted that Malayan Chinese literature was but a diasporic offshoot of Chinese literature from China and not fundamentally “unique”.2

Twenty-five articles were exchanged in this debate, including a number by a minority of contributors who sat on the fence. While there was no clear winner, advocates of the “uniqueness of Malayan Chinese literature” eventually prevailed as a result of a historical contingency. After the British declared a state of emergency in Malaya in June 1948, immigrant writers either voluntarily returned or were repatriated to China.3 Strict controls over imported reading materials from China were imposed under the Emergency Regulations Ordinance of 1948 that restricted the import, sale and circulation of publications.4 This further created a vacuum in Chinese-language literature,5 compelling Malayan Chinese writers to “seek their genius in themselves”6 and create works that spoke to locale-specific cultures and sensibilities.

Dialects and Malay in Chinese Fiction

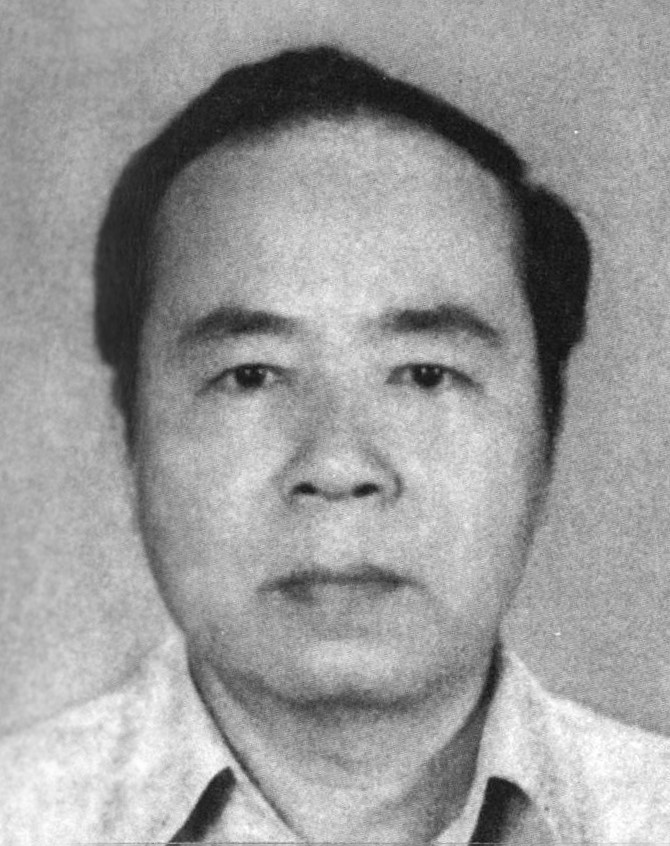

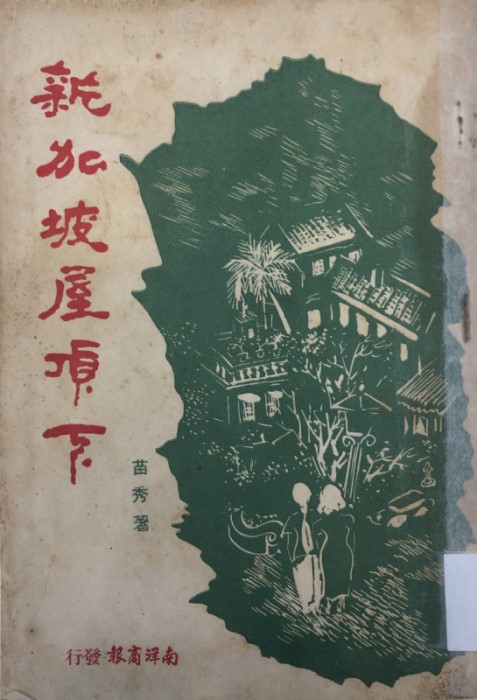

It is within this context that an interesting linguistic phenomenon emerged among a new generation of Malayan Chinese writers in the 1950s. This was namely the representation of Chinese dialects and, to a lesser extent, colloquial Malay (also known as Bazaar Malay) in fictional works composed in standard written Chinese. Miao Xiu (1920–80) was one of the most prolific writers in this period who used this technique.

Born in Singapore, Miao Xiu (under the pseudonym Wen Renjun) clearly expressed support for the Malayan-Chinese Literature School in an article he contributed to the Sin Chew Jit Poh on 28 February 1948.7 Hence, his writing unsurprisingly features Chinese dialects and colloquial expressions (including vulgarities) as the use of place-based language is one of the principal means through which the locale-specificity of Malayan Chinese literature can be manifested.

The majority of dialect segments in Chinese fiction from this period appear in dialogues, in apparent mimicry of the parole of locals, although they were occasionally found in the main narrative. Cantonese was frequently used, likely because it was one of the most widely spoken dialects among the ethnic Chinese in Malaya. Miao Xiu’s family, for instance, hailed from Canton (Guangzhou today) and was almost certainly conversant in Cantonese. Cantonese is also more readily representable in writing as compared to, say, Hokkien, as it has its own unique set of characters used alongside standard characters. Cantonese words were often peppered throughout the text, although it was not uncommon for entire stretches of dialogue to be in Cantonese, particularly for characters from the working class (characters who were intellectuals generally did not converse in Chinese dialects). Apart from Cantonese, Hokkien and colloquial Malay words also popped up, contributing to the rich linguistic texture of the literary language.

To take an example from Miao Xiu’s well-known novella 《新加坡屋顶下》(Xinjiapo Wuding Xia; Under Singapore’s Roof, 1951), consider these lines about Sai Sai, a character who reluctantly pays protection money – haggled down from five to three dollars – to a lackey of the 707 triad in exchange for protection from other gangs: “這鬼是「七0七」的「草鞋」(私會黨的總務),每逢禮拜晚就來黑巷向她賽賽討「包爺費」,為了免得別的私會黨的三星臭卡「卡周」(馬來語:欺凌),她賽賽不得不忍痛付給這鬼一筆保護費;可是這臭卡一開口就是一巴掌(五扣錢),講到口乾才減到三扣。”8

Here we see a succession of terms (in bold) that would surely baffle the non-local Chinese reader – and, for that matter, even a contemporary Chinese reader today. These include the name of a triad (七0七, or “707”), the informal term for someone who runs errands for triads (草鞋, literally “straw sandal”), the slang for “protection money” (包爺費, literally “fee for reserving the master”), the Malay term for “bully” (卡周, or kacau), the colloquial word for “five dollars” (一巴掌, literally “one slap”), and the term 扣 in Hokkien/Teochew for counting cash dollars.

On occasion, Cantonese and Hokkien were mixed within a single utterance. Miao Xiu’s book also features scenes where characters use different dialects in alternation, for example, when one person speaks in Cantonese and the other responds in Hokkien. This technique of code-switching creates a complex weave of different voices on the page, even though it also leads to a contrived linguistic style peculiar to the written form.

Annotations were often provided for terms transliterated from Chinese dialects or colloquial Malay (for instance 卡周 [ka zhou] refers to kacau in the example above). This suggests that fiction writers like Miao Xiu did not assume their readers would understand the non-Mandarin terms without assistance. For although Chinese dialects and colloquial Malay were commonplace on the streets during the 1950s, their representation in writing was, and still is, a marked practice. Indeed, there is some evidence to indicate that some readers of the day might have been alienated by the generous sprinkling of Chinese dialect words, particularly Cantonese.

In a forum article published in the Nanyang Siang Pau on 7 July 1954, one reader expressed frustration with a story written “entirely in Cantonese” published in the paper. The reader complained that Hokkien speakers like himself were unable to understand the story and maintained that literary authors should write mostly in standard Chinese.9 Hence, while the use of dialects (and colloquial Malay) in Chinese writing instantiated the “uniqueness of Malayan Chinese literature”, it was ultimately still experimental in nature.

EngMalChin andMalayan English Poetry

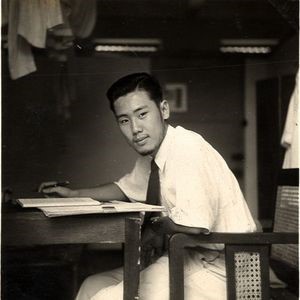

Chinese writers were not alone in experimenting with the linguistic medium of the literary arts. In the realm of Anglophone writing in Malaya, a similar development was taking place. Amid the rise of a Malayan consciousness, a group of young students at the University of Malaya came up with the novel idea of amalgamating the various languages spoken in the region to create a synthetic medium for English-language poetry. Most prominent among these young advocates was Wang Gungwu, who would later become one of the most influential historians of the Chinese diaspora.

The initiative championed by Wang and his contemporaries, dubbed EngMalChin, was an ambitious attempt to create a new literary language based on English but specifically Malayan in constitution. A portmanteau that conflates “English”, “Malay” and “Chinese”, the term “alludes to the way in which the English of a poem made room for Malay and Chinese words and phrases”.10 Most exemplary of this linguistic style is Wang’s poem “Ahmad”,11 particularly its penultimate stanza featuring code-mixing in English and Malay.

Thoughts of Camford fading,

Contentment creeping in.

Allah has been kind;

Orang puteh has been kind.

Only yesterday his brother said,

Can get lagi satu wife lah!

Insofar as the teaching and learning of English poetry in British Malaya very much subscribed to canonical classics à la T.S. Eliot and the like, the use of “Allah” (god in Islam), “Orang puteh” (white men) and “Can get lagi satu wife lah!” (Can get another wife lah!) would have been highly unusual for Wang’s readers. And therein lay the motivation for EngMalChin, specifically designed to invoke “plural imaginings of Malaya”.12

In a 1958 essay reflecting the ethos of EngMalChin, Wang reminisced that he and other student poets were “self-consciously Malayan” and were invested in the distinctiveness of English as it was used in Malaya: “What floored us was the illegitimate mixing of various languages; our stock example of this was Itu stamp ta’ ada gum ta’ boleh stick-lah [“the stamp has no glue so it can’t stick”]. What can we make of that? We could not even decide whether that was Malay with a few English words or English with a Malay syntax.”13

EngMalChin therefore thrived on an ambivalence that ensued from the fusion of different tongues. It branded itself as a linguistic signature that distinguished Malayan English from British English. In a 1950 article published in the journal Young Malayans, Beda Lim, a contemporary of Wang’s, described Malayan English as a “champurised language”; “champurised” taking reference from the Malay word champur, meaning “to mix”, creatively inflected into a past perfect form as if it were an English word.

In making a case for Malayan English as a “solution for Malaya”, Lim asserts that “Champurisation should not be frowned upon but rather should be regarded as a healthy development”, because “[a]lthough we [Malayans] use English words, the way we juxtapose them must necessarily be different from the way the English people do it”.14 Although the term EngMalChin did not appear in Lim’s article, the word champur in its various forms (“champurised”, “champurisation”) embodied the multilingual ethos of EngMalChin.

Although EngMalChin manifested itself primarily in poetry, it was not a purely aesthetic project; its sociopolitical agenda was clear from the outset. As Wang recalled: “We persisted, however, not so much for the art of poetry as for the ideal of the new Malayan consciousness. The emphasis in our search for ‘Malayan poetry’ was in the word, ‘Malayan’.”15

Before the close of the decade, however, it was clear that EngMalChin was a floundered mission. In his 1958 essay, Wang conceded that there was an inherent paradox of seeking a Malayan identity through an English-language matrix: “the most serious error was . . . the contradiction between our search for Malayan poetry and our decision to base that search on the English verse forms”.16 In addition, EngMalChin was very much a theoretical concept without a substantial empirical base. There were too few players in the game to render it meaningful.

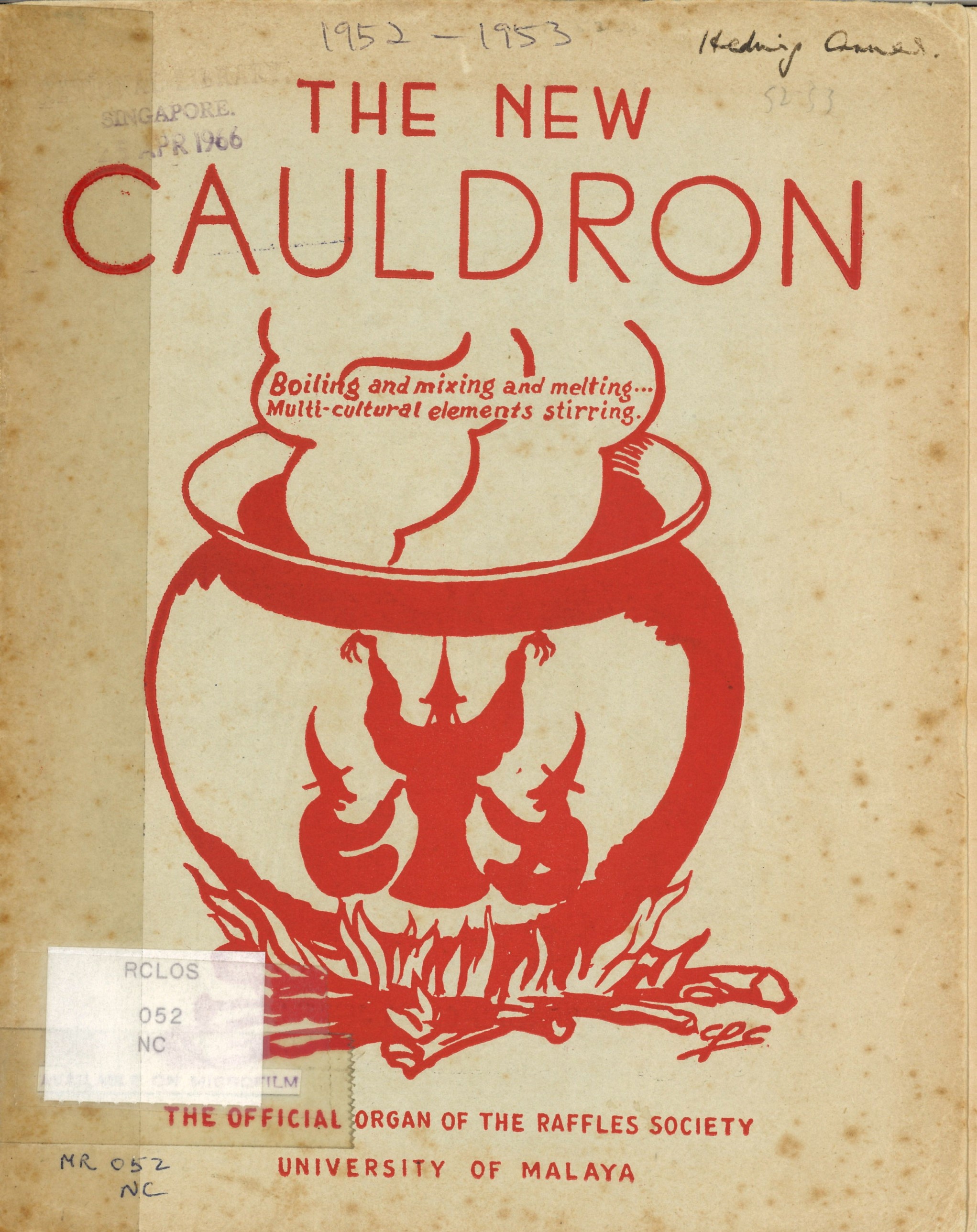

In The New Cauldron, a popular literary magazine in the 1950s edited by students from the University of Malaya, there is very scant evidence of EngMalChin, apart from a few of Wang’s own poems. The dearth of examples of “champurisation” in Malayan English poetry demonstrates that as a campaign, EngMalChin remained aspirational and never really took off in practice. Nevertheless, as a literary-linguistic ideal, it broke ground by engendering the possibility of a distinctive multilingual voice — or multivocality — for Malayan writing.

Multivocal Writing as an Expression of Linguistic Citizenship

It is no coincidence that Chinese-language and English-language writers in Malaya experimented with multivocality in their respective literary spheres within the same period. This is especially so because, as the author Han Suyin observed, there was little communication between the two communities of writers.17 It was the effervescent ambience of Malayan society in the 1950s that encouraged linguistic creativity and fostered the articulation of a unique locally grounded voice in writing. This voice was decidedly heterogeneous, with Chinese-language and English-language writers breaking with their respective literary traditions to invent an adulterated discourse that reflected the plethora of tongues spoken in Malaya.

It is through this thrown-togetherness of tongues that writers in the 1950s gesture towards what we may call an imagined utopia in Malaya. Multivocal writing, therefore, is not simply about language and literature; it is the symptom of a milieu caught in the transition from colonialism to nationalism, in which citizenship and nationality were under intense negotiation. Multilingualism as an experimental mode of writing, then, speaks to transitions in identity.

Through their experimentation with plural voices, Sinophone and Anglophone writers endeavoured to “capture the utopic experience of thinking language otherwise”,18 forging what sociolinguists call a linguistic citizenship. Linguistic citizenship refers to a condition where “representing languages in particular ways becomes crucial to, becomes the very dynamic through which, acts of agency and participation, and reconceptualizations of self in matrices of power occur”.19 This concept allows us to understand how, as a modality of expression, literary composition is tied to the fervent sociopolitics of 1950s Malaya.

Literary experimentations in that period have also left their imprint on our linguistic landscape today. Singlish, for example, can be seen as a contemporary incarnation of EngMalChin.20 Endowed with a locale-specific consciousness, Singlish now features in writing to emblematise a distinctively Singaporean ethos, just as EngMalChin had aspired to in the 1950s. Indeed, multivocality constitutes the fabric of our cultural expression today and is one of the many legacies left by our pioneer literary writers.

Lee Tong King is a Professor of Language and Communication in the School of English, University of Hong Kong. He was a National Library Singapore Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow in 2022–2023.

Lee Tong King is a Professor of Language and Communication in the School of English, University of Hong Kong. He was a National Library Singapore Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow in 2022–2023.Notes

-

Han Suyin, “An Outline of Malayan-Chinese Literature,” Eastern Horizon 3, no. 6 (June 1964): 10. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 950.05 EHMR) ↩

-

Tang Eng Teik, “Uniqueness of Malayan Chinese Literature: Literary Polemic in the Forties,” Asian Culture 12 (December 1988): 102–115. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Low Choo Chin, “The Repatriation of the Chinese as a Counter-Insurgency Policy During the Malayan Emergency,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 45, no. 3 (October 2014): 363–92. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Regulations Made Under the Emergency Regulations Ordinance, 1948 (F. of M. Ord. No. 10 of 1948) incorporating all amendments made up to the 31st March, 1953 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 348.595 MAL) ↩

-

Jeremy E. Taylor, “‘Not a Particularly Happy Expression’: ‘Malayanization’ and the China Threat in Britain’s Late-Colonial Southeast Asian Territories,” The Journal of Asian Studies 78, no. 4 (November 2019): 792, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335504060_Not_a_Particularly_Happy_Expression_Malayanization_and_the_China_Threat_in_Britain’s_Late-Colonial_Southeast_Asian_Territories. ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “A Short Introduction to Chinese Writing in Malaya,” in Bunga Emas: An Anthology of Contemporary Malaysian Literature (1930–1963), ed. T. Wignesan (Malaysia: Rayirath Publications, 1964), 252. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 828.99595 BUN) ↩

-

Wen Renjun (Miao Xiu), “On Overseas Chinese Consciousness and the Uniqueness of Malayan Chinese,” Sin Chew Jit Poh, 28 February 1948. (Microfilm no. A01597329C) ↩

-

Miao Xiu 苗秀, Xinjiapo wuding xia 新加坡屋頂下 [Under Singapore’s Roof] ([Xinjiapo] [新加坡]: Nan yang yin shua she 南洋印刷社, 1951), 6. (Emphases added). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese C813.4 MX) ↩

-

Li Wen 李文_,_ “Guanyu fangyan wenxue,” 關於方言文學 [About dialect literature], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 7 July 1954, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Rajeev S. Patke and Philip Holden, The Routledge Concise History of Southeast Asian Writing in English (London: Routledge, 2010), 51. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 895.9 PAT) ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “Ahmad”, Pulau Ujong, accessed 27 October 2023, https://www.pulauujong.org/8-2/ahmad/. Originally published in Wang Gungwu, Pulse (Singapore: B. Lim, 1950). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 828.99595 WAN) ↩

-

Brandon K Liew, “Engmalchin and the Plural Imaginings of Malaysia; or, the ‘Arty-Crafty Dodgers of Reality’,” Exclamat!on: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2 (2018): 65, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331273048_Engmalchin_and_the_Plural_Imaginings_of_Malaysia_or_the_‘Arty-Crafty_Dodgers_of_Reality’. ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “Trial and Error in Malayan Poetry,” The Malayan Undergrad 9, no. 5 (1958): 6. (From National Library, Singapore, PublicationSG) ↩

-

Beda Lim, “Malayan English: A ‘Champurised’ Language!” Young Malayans 6, no. 91 (5 July 1950): 202. ↩

-

Wang, “Trial and Error in Malayan Poetry,” 6. ↩

-

Wang, “Trial and Error in Malayan Poetry,” 6. ↩

-

Han, “An Outline of Malayan-Chinese Literature,” 16. ↩

-

Christopher Stroud and Quentin Williams, “Multilingualism as Utopia: Fashioning Non-Racial Selves,” AILA Review no. 30 (2017): 86, https://www.academia.edu/39806721/Multilingualism_as_utopia_Fashioning_non_racial_selves ↩

-

Stroud and Williams, “Multilingualism as Utopia,” 185. ↩

-

Shawn Hoo, “Singlish Modernism,” Asymptote Journal (29 Oct 2020), https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2020/10/29/singlish-modernism/. ↩