Memory, History, Art: Yip Yew Chong’s “I Paint my Singapore”

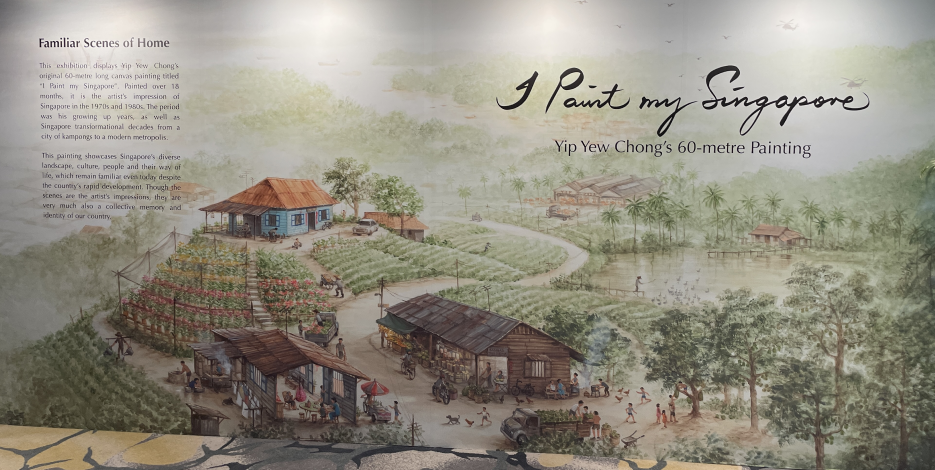

Yip Yew Chong’s 60-metre-long work, “I Paint my Singapore”, melds memories and research to produce stories about Singapore.

By Jimmy Yap

As an artist, Yip Yew Chong made a name for himself painting outdoor murals in places such as Chinatown, Kampong Glam and Tiong Bahru. He would produce huge scenes – mostly with a historical bent – while perched on a ladder, regularly battling the elements. His most recent claim to fame, however, is a little different. While undoubtedly large – “I Paint my Singapore” is a 60-metre-long work – most of the painting was done indoors in the comfort of Yip’s studio. And while outdoor murals are a transient medium, exposed as they are to the merciless sun and the pelting rain, Yip’s latest painting is meant to last.

The public’s response to “I Paint my Singapore” has been remarkable. So many people wanted to view the painting, which was exhibited at the foyer of the Raffles City Convention Centre, that the organisers had to do crowd control.

A Slice of the Past

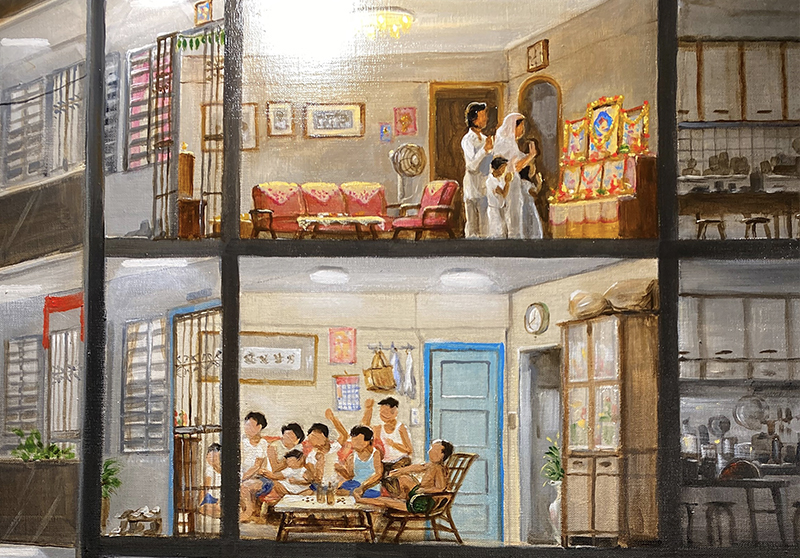

Yip’s latest work captures Singapore as it was in the 1970s and 1980s. The work (acrylic on canvas) consists of 27 panels (about the length of five double-decker buses lined up) that form a continuous scene, like a panorama, but one that switches perspective from one canvas to the next, from street scene to bird’s-eye view. Another interesting aspect is that Yip has removed the facade of some of the buildings so that people can see what’s happening inside, a little like X-ray vision.

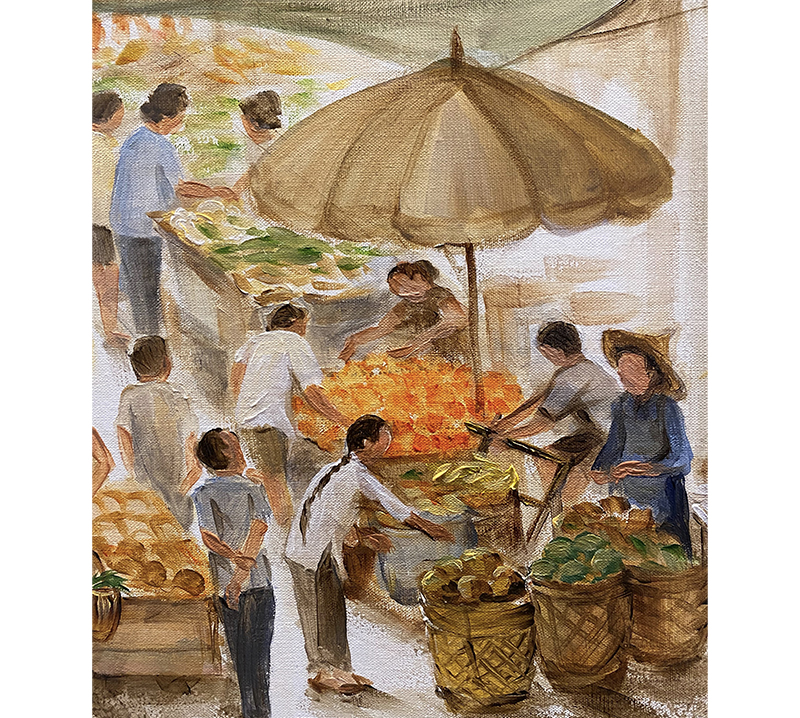

Well-known places and landmarks like the former National Theatre and Little India feature in this painting. But Yip also painted more quotidian scenes – of everyday life in housing estates and outlying areas of Singapore. These have probably had greater resonance with Singaporeans.

The atmosphere at the exhibition, where the work was displayed from 30 November 2023 to 1 February 2024, was more akin to a bazaar than an art gallery, especially in its closing days. But what was more interesting than the size of the crowd was what they were spotted doing. Rather than gazing pensively at each canvas, people could be seen animatedly discussing different scenes with their friends. Within intergenerational groups, you would often hear impromptu history lessons being conducted.

Pointing to a boat filled with recruits en route to Pulau Tekong, a father in his 40s recounted to his young daughter what it was like being ferried on that craft. “When it rained, we all got wet,” he explained, noting the lack of shelter. (She did not seem impressed by the anecdote.) A middle-aged women pointed to a hill in Jurong and told her companions, “That’s where our church is.” People also shared their favourite scenes on social media.

Yip estimates that the people who came to view his work numbered in the tens of thousands. What was it about this particular work that drew so many people and that sparked off all these conversations?

Veteran diplomat Tommy Koh, who opened the exhibition on 29 November 2023, noted that Yip’s art was accessible and called Yip “the people’s artist”. Koh said that the enormous work resonated with people because “it is such a monumental achievement and because the different panels remind people of the places they grew up in or have special memories for”.

Yip agreed that familiarity was a big part of the appeal. In response to an emailed query, Yip said he believed that the painting struck a chord with people because “they can see themselves, their families, relatives and friends; their homes, where they’ve played, worked, studied, served NS etc. in the painting”.

The 54-year-old artist said that he chose to paint scenes of Singapore of the 1970s and 1980s because the period was personally significant to him. “The decades are my growing-up years as a child and as a youth, and I have fond memories [of that time].”

Because everything has changed so much in the ensuing decades, Yip had to rely on his memory, supplemented by extensive research, to paint each scene. In a BiblioAsia+ podcast, Yip said he had spent more time thinking about the work and researching it than actually painting it.

In terms of research, a lot of time was spent online looking at photos of Singapore of that period, with the National Archives of Singapore being an important source, he said.

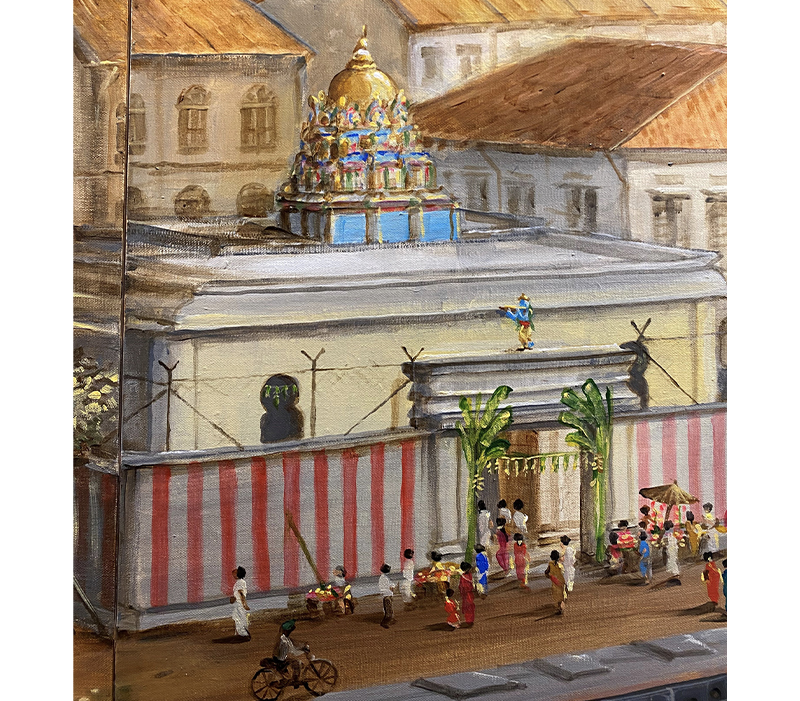

It was through his research in the archives that he discovered that the 150-year-old Sri Krishnan Temple on Waterloo Street looked very different in the 1970s from how it does today. “Today, that temple is so elaborate and so colourful,” he said. “But in the 1970s, it was just a simple temple with a gopuram [pyramid-shaped tower] on the roof and the statue of Sri Krishnan in the archway.” Thanks to his research, Yip was able to depict the temple accurately.

In addition to capturing scenes of a Singapore lost to time, what also adds charm to Yip’s work is that each scene has mini stories embedded within them.

In depicting the old Central Sikh Temple on Queen Street (the temple is now on Towner Road), Yip painted a non-bearded Sikh serving food because the artist wanted to tell the story he had read about a Chinese man who had entered the faith. “He wanted to be a Sikh, wanted to embrace the religion, but he couldn’t grow a beard… but the Sikh community welcomed him so he just wore a turban and he served in the temple and the community.”

In another scene, Yip painted a wake being held in the void deck of a Housing and Development Board apartment block. Members of the funeral band are disembarking from the lorry that brought them to the wake. Nearby, a parking attendant in a straw hat is writing out a ticket. Around the corner, a man in grey is hurrying down the road in a desperate attempt to avoid a ticket.

A Penchant for the Past

Yip is the latest cultural worker to mine history to create art. Rachel Heng’s novel, The Great Reclamation, is another example of a recent work based on occurences or events that have actually happened in Singapore. While Yip pored over old photos, Heng devoured oral history transcripts from the archives and dived into old newspaper reports from NewspaperSG, an archive of old local newspapers that the National Library makes available to the public.

This interest in history is not just coming from artists and writers, but also from the general public as well. Over the years, there has been greater interest in both preserving and revisiting the past. This can be seen in the clamour to conserve old buildings as well as the mushrooming of groups on Facebook dedicated to sharing photos and memories of days (and places) gone by.

Even if this is only driven by a very human desire to revisit the “good old days”, that has value too. For individuals, nostalgia can help improve their mood as they reminisce about life back in the day. It can also be good for society. Nostalgia creates a sense of place, a feeling of connection, generates shared stories – these all help to knit a people together.

In all fairness, it must be said that the good old days weren’t necessarily always that good. In the BiblioAsia+ podcast, Yip recalled how, at one point, there were as many as five different families living on the same floor of the tiny shophouse on Sago Lane that his family had rented. While he recalled that memory fondly, it is unlikely that many people would want to return to a Singapore where that was common.

Likewise, if you look at the scene of men unloading cargo off boats in the Singapore River, you can see that the river was filled with activity and human life. At the same time, the river itself was probably devoid of aquatic life, choked as it was with waste and effluent. The painting, of course, also fails to capture the appalling stench that the river was a byword for.

At the time of writing, Yip has yet to find a buyer for his monumental work. He said he hoped to find someone, preferably a custodian or curator, who would be able to “conserve, re-exhibit and develop it further, such as into a multimedia experience that can travel around the world”. There are probably not many individuals or institutions with the ability and space to purchase and then exhibit a 60-metre-long painting. Yip, nonetheless, is hopeful that a buyer will eventually emerge. And indeed, if the black, fetid waters of the Singapore River can be transformed into an environment where fish thrive and even otters frolic, then just about anything is possible.

Jimmy Yap is the Editor-in-Chief of BiblioAsia.