From Betty of Balmoral Road to Emily of Emerald Hill: A New Look At Stella Kon’s Classic Play

A study of early drafts of Emily of Emerald Hill reveals fascinating choices and paths not taken.

By Eriko Ogihara-Schuck

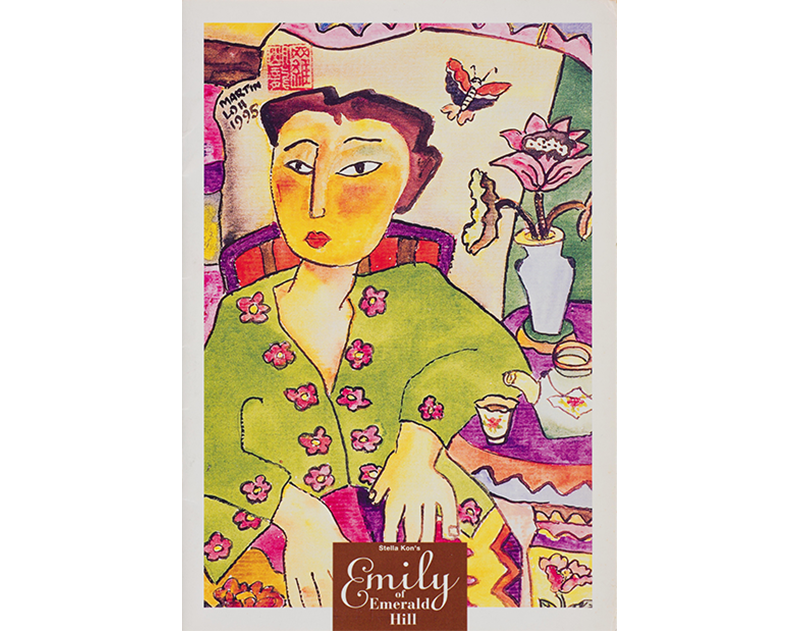

Over the last four decades, few Singaporean plays have occupied the imagination as much as Stella Kon’s Emily of Emerald Hill. Possibly the most frequently staged play in Singapore, the powerful script and the notable performances of the likes of Margaret Chan, Neo Swee Lin, Karen Tan, Laura Kee, Ivan Heng and others have inspired audiences to think about Peranakan culture and its place in the evolution of Singapore society.

While all this would suggest that the 90-minute monodrama is very well known, there are numerous aspects of Emily that few people are familiar with. Who knows, for example, that Kon had, at one point, planned to title the play Betty of Balmoral Road?

In an early version of the play, Kon also had a very different motivation in mind for a key moment, one that would cause Emily’s world to collapse. However, she decided to rewrite that scene to avoid being too clichéd. Perhaps more importantly, Kon also added another event into the play to allow Emily to redeem herself in the eyes of the audience, a scene that did not exist in early drafts.

And while very much a Singaporean story – Emily Gan is, after all, a Peranakan matriarch living in the Peranakan enclave of Emerald Hill in Singapore – the play also owes much to Singapore’s northern neighbour. Like many Singaporeans, Emily has links with Malaysia: playwright Stella Kon was living in Ipoh when she began writing the play, and indeed, Emily debuted in Malaysia.

The first-ever performance of the play took place in 1984 in Seremban, Negri Sembilan. This production by Five Arts Centre was directed by Malaysian teacher, theatre director and playwright Chin San Sooi with Leow Puay Tin as the first Emily. The play became so beloved across the Causeway that Pearlly Chua, who first began performing as Emily in 1990, has done so hundreds of times over the last three decades.

Beginnings in Ipoh

Kon, who is Peranakan, spent her formative years at 117 Emerald Hill Road and had been exposed to theatre at an early age. She was inspired by her mother, Rosie Lim Guat Kheng, who was an amateur actress, and Kon’s theatre-loving father Lim Kok Ann.1 While studying at the University of Singapore (now National University of Singapore), Kon wrote a short play titled Birds of a Feather in 1966 which was staged by the university’s students on an exchange trip to France.

Following her marriage and move to Ipoh in 1967, Kon began writing longer plays. In 1971, her double bill of two science-fiction plays, A Breeding Pair, was produced by the Ipoh Players, the resident theatre company of Ipoh’s Anglo-Chinese School. Its director was Chin San Sooi.

Kon began writing Emily of Emerald Hill in Ipoh in 1982, and completed it in Britain when she moved there for the education of her two sons. The idea for the play originally came from Ong Su-Ming, one of the leaders of the school’s theatre company. On hearing Kon lament that the plays which had earlier won her the first prize at the Singapore Playwriting Competition had not yet been staged in Singapore because they needed a large cast, Ong suggested that she write a play with a single character.2

Ong told Kon about the American playwright William Luce’s one-woman play, The Belle of Amherst (1976), based on the life of 19th-century poet Emily Dickinson.3 Ong had seen this play during a visit to Boston, and she advised Kon to write a one-woman play about Ong’s grandmother.4

Two Different Versions

Kon then began work on what would eventually become Emily of Emerald Hill. The original title was Betty of Balmoral Road, with Betty being the name of Kon’s aunt who actually did live on Balmoral Road in Singapore. But even at that early stage, the main character was inspired by Kon’s grandmother Polly Tan, who lived on Emerald Hill Road. According to Kon, Polly Tan was “the model for Emily – in character, but not in the events of her life”. Polly was “not an unwanted and abused child, her son did not kill himself”, and Kon had “never heard the slightest hint of trouble in her married life”. But Polly’s “charm, her hospitality and generosity, her robust energy and love of life – the strength of a woman who returned to Singapore as a widow [after the Japanese Occupation]” – all went into Emily.5

By the time Kon started jotting down ideas for the play in 1981, she had changed the titular character’s name to Emily while keeping Balmoral Road as the setting. Kon felt that the name Emily was more fitting than Betty given that the character was born in the 1910s. It was a pure coincidence that the name ended up being the same as the main character of The Belle of Amherst.6

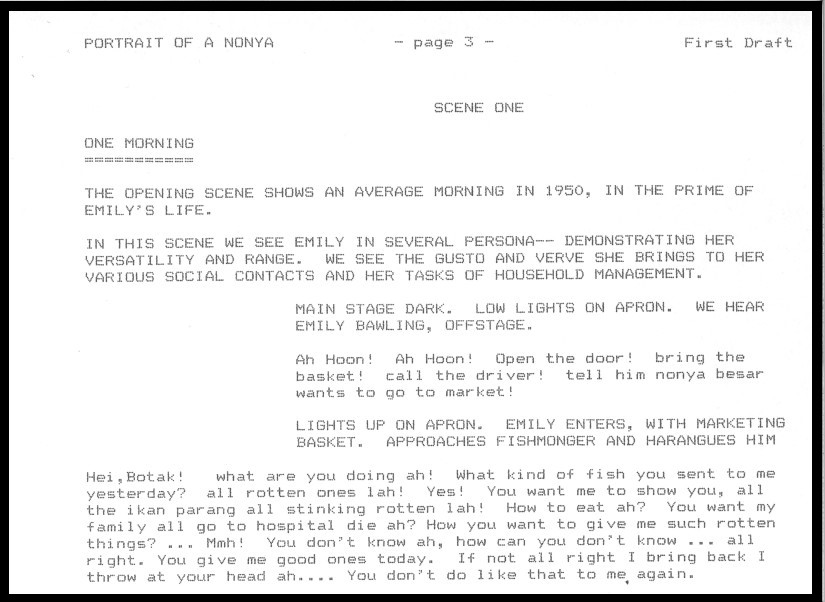

Kon then completed the first draft, by which time it had been named Portrait of a Nonya: A Monodrama. At this stage, the play was still set in Balmoral Road. This draft shows other interesting differences compared to the final script of Emily of Emerald Hill. In Emily, her son Richard commits suicide in England after she forbids him from becoming an instructor at a horse-riding school. In Portrait, however, Richard takes his own life because she rejects his marriage with a “white woman”.7 Later, Kon found this marriage scenario to be “a superficial, cheap cliché” and considered Richard’s new dream of leading a life of his own choice as generating “a more meaningful conflict”.8

In Emily, the climax of the play is when Emily accepts her daughter’s marriage to a white man in the United States. This scene did not originally exist in Portrait. Kon added this episode to give Emily “a chance for her own redemption”.9

Portrait and Emily also have different opening scenes. Portrait begins with Emily visiting the market and the audience hearing Emily bawling offstage. “Ah Hoon! Ah Hoon! Open the door! Bring the basket! Call the driver! Tell him nonya besar wants to go to market!” Then she appears on stage and, addressing the audience, says: “Hei, Botak! What are you doing ah! What kind of fish you sent to me yesterday? All rotten ones lah! Yes! You want me to show you, all the ikan parang all stinking rotten lah! How to eat ah? You want my family all go to hospital die ah?”10

The final script, however, opens with Emily speaking to people on the phone, starting with her friend Susie. “Susie ah! Emily here ah. This afternoon I’m going to town, anything that you’re needing? I’ve got the chicken you wanted from market; and I saw some good jackfruit, your children love it, so I bought one big one for you. What else you need?” Emily then calls the Adelphi Hotel and speaks “in an upper-class educated voice”.11 In Portrait, a version of this scene was situated in the middle of Scene Two.12 Kon created this new opening in order to bring the audience’s immediate attention to Emily’s linguistic code-switching and make them laugh.13

However, both Portrait and Emily have interesting parallels with The Belle. As in The Belle, the two versions are equally food-focused. In The Belle, Emily Dickinson’s first line is: “This is my introduction. Black cake. My own special recipe.”14 Portrait and Emily also open with a reference to food. Later in The Belle, Dickinson introduces the recipe of the black cake, and something similar happens in Portrait and Emily. In Portrait, there are short scenes of her servant cooking fish head curry and Emily explaining how to prepare coconut ice-cream.15 In Emily, the fish head curry is deleted but coconut ice-cream is retained, and detailed instructions about how to cook the traditional Peranakan dish babi buah keluak are added.16

The Belle ’s techniques are also visible in Portrait and Emily. In the opening scene of Emily, Emily converses with invisible characters on the telephone. This technique is also used in The Belle, for instance, in the scene when young Dickinson’s father scolds her for staying up late, and she explains to him that she is writing poetry.17 Interestingly, Kon had not watched The Belle. It was her own “solution” to let the main character converse with invisible characters.18

In the market scene, Emily breaks the fourth wall just as Dickinson does. At the very beginning, Dickinson turns the audience into fellow actors: by serving them a cake, she invites them as guests into her parlour.19 Likewise, Emily turns the audience into stall owners as she appears on an extension of the main stage, known as an “apron”,20 and moves closer to her audience.

Like the telephone scene, this original opening scene also vividly shows Emily’s ability to switch between Singlish and Queen’s English, and to speak in Hokkien and Malay. After speaking with Botak in Singlish, Emily turns to Ah Soh who sells vegetables and asks: “[H]ow are you, gou cha [so early]? Ya I’m fine, family is fine, chin ho, chin ho [very good, very good].” Later, she enters Cold Storage and speaks in a “posh accent”: “Morning, Mr Chai! Have you got my baked ham? I ordered it yesterday – yes in my name, Mrs Gan Swee Kheng, have you got it there?”21 But by additionally involving the audience in the play, this scene more powerfully illustrates both multiracial Singapore as well as Emily’s ability to straddle different worlds, a characteristic of the Peranakan Chinese.

Premiere in Seremban

Almost from the beginning, Emily of Emerald Hill was recognised as an important work. Kon submitted the play to the 1983 Singapore National Playwriting Competition and won the first prize (for the third time). But the form of the play posed new challenges to the Singapore theatre community. In correspondence with me, Kon speculated that the hesitation was perhaps because the monodrama format was still relatively new to local theatre.22

In Kon’s absence (she had moved to Britain by then), her friend Ong Su-Ming again took the initiative. In April 1984, Ong showed the Emily script to her former ACS Ipoh colleague Chin San Sooi, who had earlier directed Kon’s A Breeding Pair.23 This was because, among other things, Ong knew that Chin had innovatively staged a monologue play starring the up-and-coming actress Leow Puay Tin.24

Chin immediately saw the potential in Emily and quickly cast around for a producer and a sponsor while starting rehearsals with Leow.25 On 17 November 1984, at the Cemara Club House in Seremban, Leow made Emily come alive on stage.26 When the play was staged in Kuala Lumpur about two weeks later, it gained widespread coverage and triggered a reviewer to describe the production as “scor[ing] another impressive credit” and a “superb effort”.27 He also praised Leow for “captivat[ing] the audience with her near-immaculate nuances of the various periods of her life” and “inject[ing] a fresh enthusiasm into the character of Emily”.28

This Malaysian premiere was likely a major factor that prodded Singapore to finally stage Emily in 1985 at the Singapore Drama Festival. Malaysian director Krishen Jit commented that “Kon is better received in his country [Malaysia] than her own because her experimental methods go down better north of the Causeway”. In response, Singaporean playwright Robert Yeo, who was then chair of the Drama Advisory Committee at the Ministry of Community Development, denied that Singapore was not accepting enough of experimental theatre. “Singaporeans are just asking themselves whether they can produce Stella’s plays,” Yeo said. “I don’t think we are averse to experimental theatre at all.”29

Singaporean director Max Le Blond said he was immediately intrigued on reading the script.30 Actress Margaret Chan was similarly smitten. “I liked it and said yes right after I read it. I memorised the script within two days.”31 Chan’s performance mesmerised Kon. After watching it at the 1985 Singapore Drama Festival, Kon told the audience: “Margaret gave it flesh and breath and blood.” Later, she went backstage to congratulate Chan and told her: “I’m exhilarated, I’m over the moon.”32

Achieving Cult Status

Even as Emily grew in cult status in Singapore, the same happened in Malaysia. In Malaysia, the play was first perceived as delving into a “relatively little known Malaysian sub-culture” (referring to Peranakan culture).33 But it eventually came to exemplify Malaysia’s cultural diversity,34 and earned “a special place in the annals of Malaysian theatre”35 as Malaysia’s longest-running play.36

By 2002, Chin had staged Emily a hundred times (21 times with Leow Puay Tin) and the Malay Mail cheekily called the play an “obsession” and “a sheer waste of creative talent and energy to be specialised in the creative paranoia of one play”.37 But Chin continued to stage it with Pearlly Chua, who has since performed the role 214 times as at December 2023.38 The versatile Chua has also performed the play in Mandarin which, according to her, is “more physically demanding because the language uses different sets of muscles in the mouth and throat compared with English”.39

Their fascination with the play is, of course, a crucial reason for its longevity. Chin calls the play a “gem whose beauty is its universality”,40 and credits it for allowing the actor and the director to grow. “It has been a very personal development for myself. Through directing the play, I see more and more of certain things about the play, like life and values,” he said.41 Chua feels the same: “It’s a challenging role certainly and although I have done it many times, it is something I find I can discover something new every time I approach it.”42

But audience demand is an important factor as well. After all, if no one buys tickets, no theatre company can afford to produce the play. “I stage the play every year because people ask me to do so,” Chin said.43 Woo Yee Saik, who produced Chin’s Emily in 2002 in Georgetown, Penang, and would go on to produce four more Emily performances, said that he has met many people, both Peranakans and non-Peranakans, who told him that they have someone similar to Emily in their family – either their mother, grandmother or aunt.44

My Personal Experience with Emily

I watched Emily live on stage for the first time in Kuala Lumpur in July 2023. Watching the play in person was a much more intense experience than watching the online videos (of Pearlly Chua, Margaret Chan and Laura Kee). I remember most vividly the scene where Emily was meant to cry. Chua actually did not cry as the tears did not roll down her face. Instead, the tears just pooled in her eyes which made her eyes shine under the bright stage lights. To me, this was more poignant than if she had actually cried.

One of the attractions of the play is its ability to foster community bonding. I saw many Peranakan women among the audience wearing the sarong kebaya (an outfit made up of a sheer embroidered blouse paired with a batik sarong). The play definitely provided an opportunity for the Peranakans to come together and celebrate their culture and heritage.

Community bonding also took place within the play between Emily and the audience as well as among the audience, and it left a deep impression on me. I was thrilled to see Emily suddenly approaching the audience during the market scene. In another scene, during the birthday party for Richard, the entire audience was invited to sing “Happy Birthday” to him. It was truly amazing to feel that, by seeing Emily coming down to us and by singing for her son, I was being included in her huge multiracial and multicultural community.

Since 2024 is the 40th anniversary of Emily’s debut on the stage, it is also perhaps a good time for me, and for audiences in Malaysia and Singapore, to send birthday wishes to Emily, both the character and the play. Happy birthday Emily! Here’s to another 40 years! Or as the Peranakans would say at auspicious occasions: “Panjang-panjang umor! [Long life!]”

Dr Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, originally from Japan, is a lecturer in American Studies at TU Dortmund University in Germany. She is the author of Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad: The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes by American and German Audiences (McFarland, 2014).

Dr Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, originally from Japan, is a lecturer in American Studies at TU Dortmund University in Germany. She is the author of Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad: The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes by American and German Audiences (McFarland, 2014). Notes

-

Correspondence with Stella Kon, 19 November 2023; Nureza Ahmad, “Stella Kon”, in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2018. Kon started writing plays while still in school. At age eight, she wrote her first play, The Fisherman and the King, while at Raffles Girls’ School (RGS), which was later staged at the school. At age 12, her second play, The Tragedy of Lo Mee Oh and Tzu Lee At, a parody of Romeo and Juliet, was again performed in RGS. Kon is a descendant of Lim Boon Keng and Tan Tock Seng, who were her paternal great-grandfather and maternal great-great-grandfather respectively. ↩

-

Stella Kon, oral history interview by Michelle Low, 9 August 2006, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 22 of 36, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002996), 2:36–39. ↩

-

Stella Kon, oral history interview, 9 August 2006, Reel/Disc 22 of 36, 3:03–16. ↩

-

Stella Kon, oral history interview, 9 August 2006, Reel/Disc 22 of 36, 4:11–21. ↩

-

Stella Kon, “Fact and Fiction in the Play,“ in Emily of Emerald Hill: A One-Woman Play (Singapore: Stella Kon Pte Ltd, 2017), 60–61. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING S822 KON) ↩

-

Correspondence with Stella Kon, 3 December 2023. ↩

-

Stella Kon, Portrait of a Nonya: A Monodrama, unpublished manuscript, 1980, 16. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS S822 KON) ↩

-

Correspondence with Stella Kon, 18 March 2024. ↩

-

Correspondence with Stella Kon, 18 March 2024. ↩

-

Kon, Portrait of a Nonya, 3. ↩

-

Kon, Emily of Emerald Hill, 3. ↩

-

Kon, Portrait of a Nonya, 7. ↩

-

Correspondence with Stella Kon, 27 March 2024. ↩

-

William Luce, The Belle of Amherst (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1978), 2. ↩

-

Kon, Portrait of a Nonya, 8; 17. ↩

-

Kon, Emily of Emerald Hill, 38–39 ↩

-

Luce, The Belle of Amherst, 22–24. ↩

-

Stella Kon, oral history interview, 9 August 2006, Reel/Disc 22 of 36, 3:23–54. ↩

-

It was a “superb solution” on the part of William Luce to involve the audience in the play in this manner. Correspondence with Grant Hayter-Menzies, 3 April 2024. For the detailed episode about how Luce came up with this solution, see Grant Hayter-Menzies, Staging Emily Dickinson: The History and Enduring Influence of William Luce’s The Belle of Amherst. Jeffferson (NC: McFarland, 2023), 119–20. ↩

-

Kon, Portrait of a Nonya, 3. ↩

-

Kon, Portrait of a Nonya, 3–4. ↩

-

Correspondence with Stella Kon, 20 March 2024. ↩

-

Correspondence with Chin San Sooi, 5 December 2023; “Director’s Chair,” Stella Kon’s Emily of Emerald Hill, https://emilyemerald.tripod.com/directorsays.htm. ↩

-

Correspondence with Ong Su-Ming, 13 November 2023. The play is I Have Not Forgotten the Dumb, a devised piece staged in 1981. ↩

-

Correspondence with Chin San Sooi, 5 December 2023. A few years after staging Kon’s A Breeding Pair, Chin impressed the German Embassy in Malaysia in 1974 by successfully staging German playwright Bertolt Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle in an innovatively minimalist style, using only 10 actors instead of the original 50. In Lady White, the very first play Chin wrote and directed in 1976, he creatively turned the audience into a fellow actor by making an actor approach someone in the audience to read his fortune. His Refugees: Images, a critique of the Malaysian government’s treatment of refugees, completed in 1980, was meant to become the first Malaysian musical although it was banned from being performed for two decades. ↩

-

Correspondence with Chin San Sooi, 5 December 2023. The premiere was done in an ad hoc manner, with a temporary stage and electricity drawn from the main office for lighting and air-conditioning. ↩

-

J.C. Forou, “A Story Told, a Cultural Sub-Type Vitalised,” New Straits Times, 2 December 1984. (From KLIK) ↩

-

Forou, “A Story Told, a Cultural Sub-Type Vitalised.” ↩

-

“A Woman of Many Faces,” Asiaweek, 21–28 December 1984, 33. ↩

-

Correspondence with Max Le Blond, 28 December 2023. ↩

-

Correspondence with Margaret Chan, 5 January 2024. ↩

-

Rebecca Chua, “Tears and Smiles Greet Emily,” Straits Times, 6 September 1985, 21. (From NewsaperSG) ↩

-

Forou, “A Story Told, Cultural Sub-Type Vitalised.” ↩

-

Ong Kian Ming, “Preserving Our Cultural Diversity for Posterity,” New Straits Times, 21 October 2002, 10. (From KLIK) ↩

-

“Pearlly’s Emily Turns 100,” Malay Mail, 10 October 2002, 29. (From KLIK) ↩

-

As at July 2005, Emily of Emerald was recorded as the longest-running play in Southeast Asia. See Noor Husna Khalid, “Chua to Reprise Emily Role for 114th Time,” Malay Mail, 6 June 2005, 10. (From KLIK) ↩

-

“Enough of Emily,” Malay Mail, 18 October 2002, 28. (From KLIK) ↩

-

Correspondence with Chin San Sooi, 27 December 2023. ↩

-

Tan Gim Ean, “‘Monologues’ Sees 3 Interpretations of ‘Emily of Emerald Hill’ and 17 Key Characters from Shakespeare,” Options, 8 July 2019, https://www.optionstheedge.com/topic/culture/monologues-sees-3-interpretations-emily-emerald-hill-and-17-key-characters-shakespeare. ↩

-

Correspondence with Chin San Sooi, 27 December 2023. ↩

-

“A Moment Please, San Sooi…,” New Sunday Times, 1 December 2002, 10. (From KLIK) ↩

-

“Emily of Emerald Hill to Be Restaged,” Malay Mail, 30 November 1998, 1. (From KLIK) ↩

-

Correspondence with Chin San Sooi, 15 July 2023. ↩

-

Correspondence with Woo Yee Saik, 13 March 2024. ↩