A Cool Business: The History of Ice–Making in Singapore

Ice has been an indispensable commodity in tropical Singapore since the late 19th century.

By Goh Lee Kim

There’s nothing like downing an ice-cold drink on a scorching hot day. And in Singapore, hot days are aplenty. But the option to grab a cold drink wasn’t always readily available. Before mechanical ice-making was invented, ice had to be imported into Singapore. Blocks of ice were cut out from frozen lakes and rivers and shipped in, a journey that would take many months. Of course, by the time the cargo arrived, up to half of the ice would have melted despite the thick sawdust insulation.

The lack of ice and refrigeration meant that food items like meat and fish were highly perishable. “At present meat requires to be cooked on the same day on which it is killed and the consequence is that it is but too frequently most horribly tough and difficult of mastication,” reported the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser in 1845.1 European residents missed their cheese, butter and fruits such as apples and grapes. For long-term meat storage, meats were preserved or cured using methods like adding saltpetre (potassium or sodium nitrate).

Whampoa’s Ice House

In 1854, prominent merchant Hoo Ah Kay (better known as Whampoa) and his partner Gilbert Angus began to import natural ice from America for his Ice House in Boat Quay. This provided residents in Singapore with their first supply of ice. “A great boon has been conferred upon the community of Singapore by the establishment of an ice house which has now been in operation for several months,” the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported. “We trust that the spirited projectors of this public benefit will receive such support and encouragement as to induce them to render their undertaking a permanent one.”2

Sadly, the venture did not last more than three years and by 30 November 1857, Whampoa had left the partnership due to heavy financial losses.3

American company Tudor Ice took over Ice House in 1861 but did no better, also incurring losses and leaving frustrated residents stranded with supply disruptions stretching months. “It was repeatedly stated by Mr [Frederic] Tudor’s managers that the consumption was not nearly sufficient to meet the cost of the ice and other expenses, and that a loss had been incurred by that gentleman of nearly $20,000, and further that unless a much greater quantity was sold the supply must be stopped,” the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported in December that year.4

Fortunately, for Singapore residents, 1861 was also the year that Singapore Ice Works opened its doors on River Valley Road. In August, the company became the first to make and sell ice produced locally. It was sold for three cents per pound, two cents lower than imported ice. The company’s proprietor, Riley, Hargreaves & Co., had sunk in a fortune to procure the latest ice-making machinery for the venture, which quickly gained public support due to its more stable supply compared to Tudor.5

“The public must now decide whether it will support an establishment which will ensure a permanent supply of ice [Singapore Ice Works], or give the preference to a person who offers no guarantee that he will keep up a more regular import [Tudor] than has hitherto been the case,” wrote the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser in December 1861. By 1865, Tudor had closed after the government enforced the sale of Ice House to Singapore Ice Works over the former’s supply disruptions.6 (The building once occupied by Ice House continued to stand in Boat Quay until it was demolished in 1981 for the widening of River Valley Road; a replica in Clarke Quay is still around today.7)

A Necessary Commodity

Other companies began to enter the market, increasing the overall supply of ice to the island. Singapore Ice Works thrived as the main ice factory until February 1881 when Straits Ice Company, owned by Howarth, Erskine & Co., began operations.8

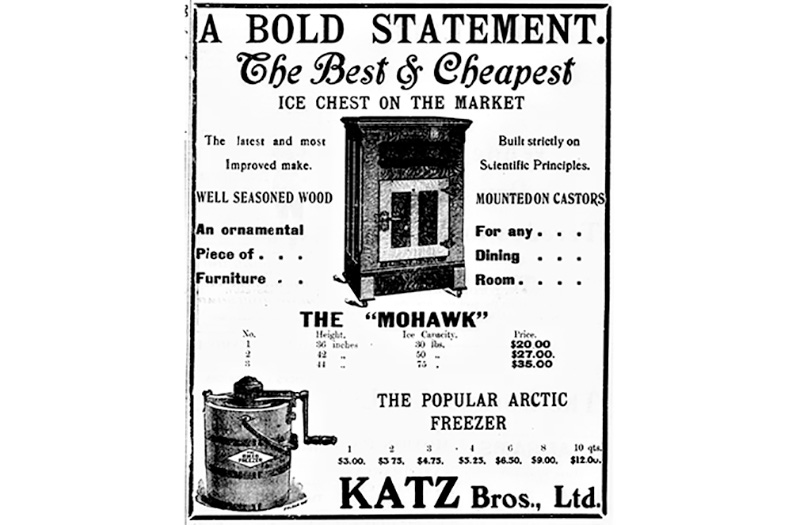

The resulting price war ended with the sale of Singapore Ice Works in June 1882 to Howarth, Erskine & Co., which amalgamated both companies and appointed Katz Brothers as its agent, selling a pound of ice at one-and-a-half cents.9 The Singapore Distilled Water Ice Company (later renamed New Singapore Ice Works) subsequently opened in March 1890.10 The factory used to be at Sungei Road until it relocated in 1984. Thanks to the factory, the area became known as Gek Sng Kio (结霜桥, meaning “Frosted Bridge” in Hokkien).11

By the 1890s, ice was seen as a necessity. An article in the Straits Budget in January 1897 waxed lyrical about ice. “Where should we be without it! We might, at a pinch, do without many things. Whiskey, for instance, might go, though heaven forfend; we could even abolish the harmless necessary soda; but ice we cannot do without. Ice is like the dew from heaven; it blesses all alike. It cools parched palates and heated brows; it is a boon either in the sick chamber or the banquetting hall.”12

A lack of cold storage facilities still prevented residents from obtaining meat, dairy and produce from further afield though. Similarly, tropical fruits from the region could not be exported to Europe. In December 1898, the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser proposed having “a cold storage establishment in Singapore as a depot not only for fruit export but meat import and distribution”. “Consider how even tinned butter would gain by issue in a firm state instead of the nauseous oily condition that it presents on opening a tin [without cold storage],” the paper added.13

The availability of clean, imported frozen food became a reality in 1903 with the establishment of the Cold Storage Company in Singapore, which brought into the market frozen meat, fruit and dairy products from places as far away as Australia. Since ice was an essential component in its business, the company soon expanded into ice manufacturing in 1916 with its own plant. Its strategic location at Borneo Wharf in New Harbour (Keppel Harbour today) meant that ice could be quickly loaded onto ships, giving it an edge over its competitors.14 By 1919, Cold Storage had emerged as the main manufacturer of ice in Singapore.15

An Appetite for Manufactured Ice

The early 20th century saw the trade of natural ice slowing globally as ice-making technology improved. In Singapore, ice-making was given a boost thanks to the steady source of water from the municipal supply and the introduction of electricity. “The major percentage of commercial ice today is manufactured. Natural ice for commercial purposes is practically a thing of the past,” reported the Singapore Free Press in January 1926. “It has been adjudged inferior because of its dirtiness, its poor crystalline structure, which causes it to melt rapidly, and the difficulty of handling it because of its irregular shape.” The paper added that “human ingenuity has perfected machinery with which clear, wholesome ice can be manufactured without complications, and at such a low cost that the dealer in natural ice finds it unprofitable to compete”.16

Usage of ice for domestic and commercial purposes also grew in tandem. Ice was sold and delivered to residences and businesses here mainly through subscriptions to the ice works, while non-subscribers had to purchase tickets for the ice.17

Domestically, ice was used to keep food fresh or chilled before refrigerators arrived in Singapore in the 1930s.18 Affluent families would store perishable foods and dairy products in insulated ice chests, which were kept cold with regular replenishments of ice.19 “The box would be made of wood,” recounted Aloysius Leo De Conceicao, a former bank officer and funeral minister. “But inside the box it was lined with a zinc or aluminium piece so that you could take out the ice and wash it and put back the ice… And then you put whatever you wanted, you wanted to chill your drinks or you wanted to keep a little things frozen or your leftover foods, you could keep it there.”20

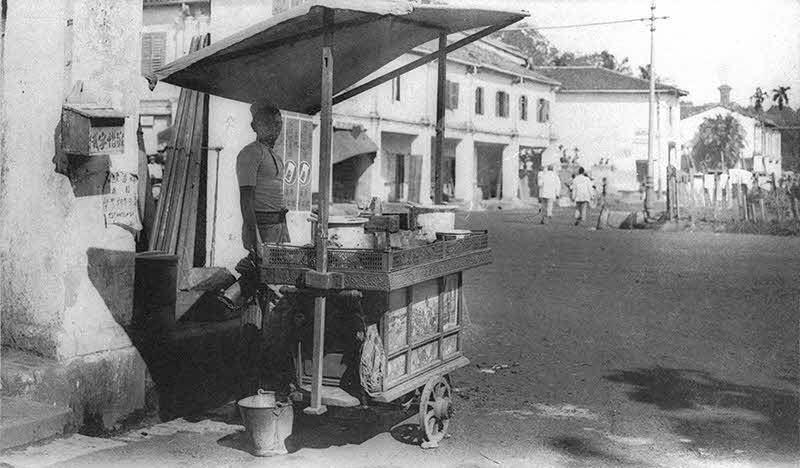

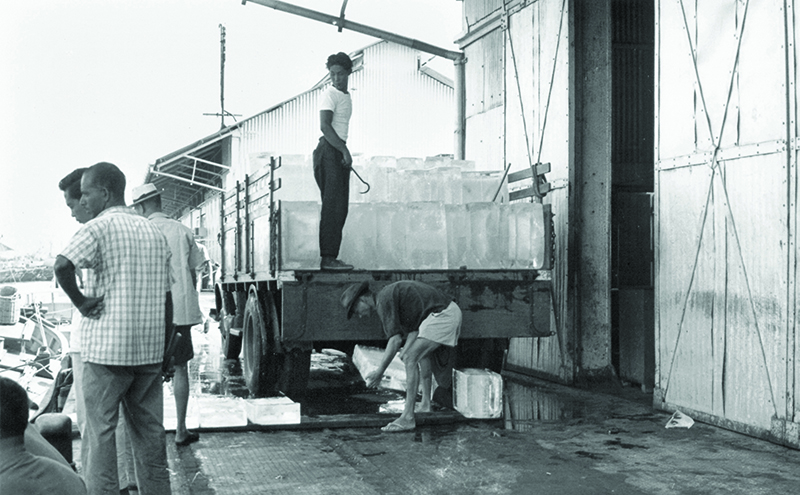

As factories traditionally sold ice in large blocks, consumers who required smaller amounts turned to ice sellers, who would purchase ice blocks from the factories and resell them in smaller pieces. The work was arduous as ice sellers had to manually haul heavy blocks of ice each day using sharp hooks and cut them into smaller pieces before delivering the ice to buyers using trucks, carts and even bicycles.

There were many of such small-time ice sellers in the 1950s and 1960s, but the numbers had dwindled by the 1980s. “There used to be three of us selling ice all within sight of one another. But that was in the fifties and sixties when Bukit Timah Road at the seventh mile was packed with drink carts,” ice seller Lim Lian Heng, 71, told the New Nation in 1980. “It’s [now] almost impossible for anyone to want to do such work. How many young men want to lug 70 katis of freezing ice with their bare arms 30 to 40 times a day?”21

An Indian ice seller, 1900s. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An Indian ice seller, 1900s. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Ice manufacturing was a very competitive business though. Even before Cold Storage opened its plant in 1916, there were already five ice factories in Singapore: Straits Ice Company (arguably the largest factory then), New Singapore Ice Works, Kallang Ice Works, Singapore Ice Factory and Chan Ngo Bee Ice Factory.22 By the 1920s, the industry had consolidated into three main players: New Singapore Ice Works, Cold Storage and Atlas Ice Company of Malacca, which opened in 1925.23

In the 1930s, refrigerators began replacing ice chests in homes, and domestic usage of ice declined.24 But ice-making remained a crucial industry commercially, especially to the flourishing fishing trade which required high-grade ice to keep catches fresh. By 1932, about 150 tons of ice were still produced daily in Singapore, mainly by Cold Storage and New Singapore Ice Works.25

Impact on the Price of Fish

During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), many ice factories were destroyed in bombing raids, and fell into disuse and disrepair. When the war ended, the ice companies attempted to restart operations, including Cold Storage. “Much of our plant and equipment suffered severely from neglect during the Japanese regime and we have had to meet, and are still facing very heavy replacement and renewal expenditure,” the company reported in a circular to shareholders in August 1948. “Prewar activities in all directions have, however, been fully resuscitated and, in many directions, considerably extended.”26

As ice production was stymied by old and damaged machinery, and replacements from overseas were delayed, the price of ice spiked. A black market by “middlemen manipulating deals between ice manufacturers and the ultimate consumers” further drove up prices, from $22.40 per ton in 1946 to more than $100 per ton in 1947. This threatened the survival of many fishing companies which could not afford to purchase the ice.27 Fortunately, by 1948, the situation improved as new machines arrived and the black market was stamped out. Amid intense competition among ice manufacturers, prices dropped to $20 per ton in 1949, benefitting both businesses and households.28

Ice was such an integral component of the fishing industry that when local ice factories attempted to raise prices to $22.40 per ton in July 1952, fish dealers and merchants protested against the “unjustified” and “unwarranted” price increase, which they claimed would “not only add to the cost of living, but also increase the price of fish”.29

In a joint letter issued by the Singapore Fish Merchants’ Association and Singapore Wholesale Merchants’ Association, they wrote that “we have now decided that it will no longer be possible to bring into Singapore second and third grade fish, for fear of incurring financial losses”. The ice manufacturers backed down, at least, at that point.30 Over time though, the price of ice continued to climb – reaching $34.20 per ton in June 1979 – impacting the cost of fish for residents.31

A Cool Business

Meanwhile, more ice factories came and went in the second half of the 20th century. After the acquisition of New Singapore Ice Works by Cold Storage in 1958, of the major factories that had operated in Singapore in the 19th century, only Cold Storage and Atlas Ice remained in business.32

In addition to these large companies, there were also others. One well-known ice supplier is Tuck Lee Ice, which has been in operation here since 1924. Originally owned by Kwok Ku Loong,33 it was sold to Hauw Kiat in 1957, an immigrant from China who moved to Indonesia and later Singapore. Hauw’s descendants took over the business after his death in 1961 and successfully modernised ice-making by introducing food-grade ice hygienically made by machines. They also sold ice in smaller cubes that were more convenient compared to the conventional larger blocks of ice typically sold by other ice manufacturers. The company has since ventured into providing ice sculptures for events, beverage distribution, and transport and logistics services for temperature-sensitive items. The Hauw family still owns and manages the company to this day.34

Another supplier that has rejuvenated the ice industry and continues to thrive in Singapore today is Jurong Marine Cold Storage (JM Ice), established in 1971. In 2015, the company moved away from the industry’s traditional reliance on tough physical labour by investing in robotic automation in its packaging process. “We were facing a big headache as no one wanted to work as an ice-packer,” said Eric Lee, one of the company’s two executive directors. With the robotic arms, its workers were redeployed to other jobs.35

Given Singapore’s tropical climate, ice manufacturers will never face a chilly reception from the market.

Goh Lee Kim is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that curates and promotes access to the library’s digital collections.

Goh Lee Kim is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that curates and promotes access to the library’s digital collections.Notes

-

“The Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 28 August 1845, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Annual Retrospect, 1854,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 5 January 1855, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Notice,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 6 May 1858, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Singapore Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 5 December 1861, 3; “Our Ice Supply,” Straits Times, 26 August 1865, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Ice Works,” Straits Times, 10 August 1861, 4. (From NewspaperSG); “Singapore Ice Works River Valley Road,” Singapore Daily Times, 24 April 1878, 1; “The Singapore Free Press.” ↩

-

Ismail Kassim, “Godown Was a Huge Fridge,” New Nation, 25 January 1975, 12; Sharon Yeo, “Step Nearer That Dream,” Straits Times, 4 April 1981, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Straits Ice Company,” Singapore Daily Times, 16 February 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Reuter’s Telegram,” Singapore Daily Times, 16 June 1882, 2; “Singapore Ice Works and Straits Ice Company,” Singapore Daily Times, 20 June 1882, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commission,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 29 December 1891, 10; “A Visit to the New Singapore Ice Works,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 3 March 1898, 145. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Victor R. Savage and Brenda S.A. Yeoh, Singapore Street Names: A Study of Toponymics (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2023), 396–97. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 915.9570014 SAV-[TRA]); “In Pictures: Sungei Road Through the Years”, Straits Times, 5 July 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/multimedia/photos/in-pictures-sungei-road-through-the-years. ↩

-

“Local Industries,” Straits Budget, 5 January 1897, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cold Storage (Nov. 30th),” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 1 December 1898, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Cold Storage Holdings (Singapore), The Cold Storage Group of Companies 1903–1978 (Singapore: Cold Storage Holdings, 1978), 4. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 338.76413 COL); “New Singapore Ice Works,” Straits Times, 3 April 1906, 5. (From NewspaperSG); K.G. Tregonning, The Singapore Cold Storage, 1903–1966 (Singapore: Cold Storage Holdings Ltd, 1967), 13. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 664.02852 TRE) ↩

-

Goh Chor Boon, Technology and Entrepôt Colonialism in Singapore, 1819–1940 (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2013), 181. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 338.064095957 GOH) ↩

-

“The Passing of Natural Ice,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 14 June 1926, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Notice,” Singapore Daily Times, 16 February 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Big Shipment of Refrigerators,” Malaya Tribune, 20 May 1936, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Refreshment in Refrigeration,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 12 August 1930, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Aloysius Leo De Conceicao, oral history interview by Zaleha Osman, 1 December 1998, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 13 of 22, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002057), 142. ↩

-

“Our Very Own Mr Chips,” New Nation, 9 March 1980, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Selangor Ice Ring,” Straits Times, 30 December 1925, 10; “Our Ice Supplies,” Malaya Tribune, 11 February 1915, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A New Singapore Factory,” Straits Times, 15 November 1932, 2; “Cold Storage Co.,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 30 April 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tregonning, The Singapore Cold Storage, 1903–1966, 26. ↩

-

“Ice Production in the Tropics,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 2 January 1932, 25; “A New Singapore Factory,” Straits Times, 15 November 1932, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Cold Storage to Increase Capital,” Morning Tribune, 19 August 1948, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Ice Shortage Hits Fisheries,” Singapore Free Press, 19 August 1947, 5; “Merchants Allege Ice Black Market,” Straits Times, 31 August 1947, 7; “Ice Black-Market Is Broken,” Straits Times, 16 January 1949, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ice Black-Market Is Broken”; “Fall in Ice Prices,” Straits Times, 20 July 1949, 8; “Ice Was Cheaper,” Singapore Free Press, 23 July 1949, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“2 Groups Oppose Ice Price Rise,” Singapore Standard, 24 June 1952, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Ice Men Give in on Price,” Straits Times, 12 July 1952, 7; “So Singapore Will Get Less Fish,” Straits Times, 2 July 1952, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

K.L. Chan, “Co-operative for Ice Water,” New Nation, 28 June 1979, 3; “Ice to Cost More for Fish Traders,” Straits Times, 29 June 1979, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Activities and Products,” Straits Times, 10 July 1972, 13; “It’s a Problem in Singapore with Temperature in 80s,” Singapore Free Press, 28 August 1959, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Ice Factory Fire Sequel,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 10 July 1930, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gabriel Chen, “Tuck Lee Ice Gets Cooler with Time,” Straits Times, 22 August 2007, 47; “This Company Hit the Bigtime With Its Frozen Assets,” Straits Times, 9 August 2005, 90; Smita Krishnaswamy, “Ice King Adds on Beverages,” Straits Times, 16 September 2009. 43. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Prisca Ang, “JM Ice Keeps Things Cool with Bots and Tech,” Business Times, 16 June 2015, 26. (From NewspaperSG); “Profile,” JM Ice, last accessed 31 January 2024, https://www.jmice.com.sg/pages/profile. ↩