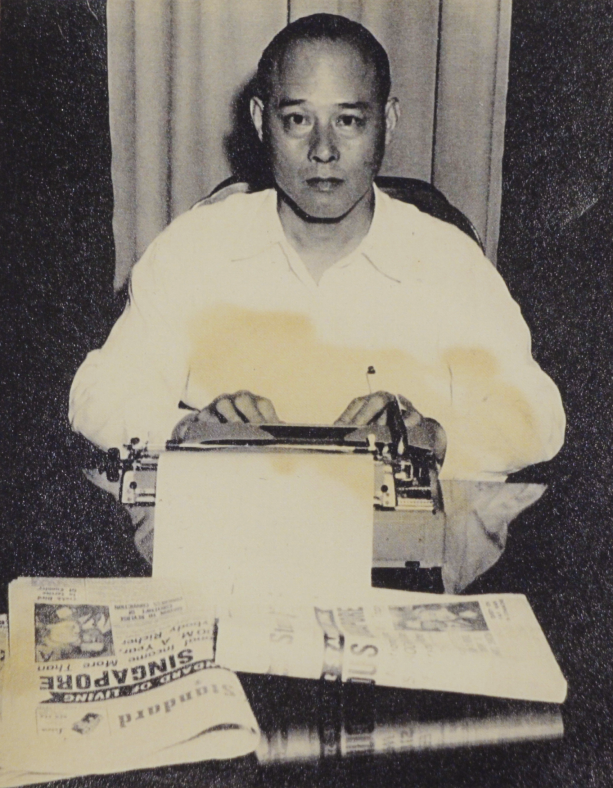

Pioneering Local Journalist R.B. Ooi

As a journalist, R.B. Ooi always had his finger on the pulse of Malaya, bringing to the fore issues at the heart of the nation.

By Linda Lim

Being in a war zone is always dangerous, even for non-combatants, as R.B. Ooi, the former editor for the Singapore Standard and the Eastern Sun, could attest.

During the Malayan Emergency (1948–60), Ooi worked as a press officer to General Gerald Templer, the British High Commissioner for Malaya, who had been tasked to deal with the communist guerillas. In a 1969 letter to his daughter, Mrs Irene Lim, Ooi wrote that he had spent three years “covering the jungle war for the government, local and foreign press”. That meant spending time with British troops in the jungle. And while they tried not to draw attention, apparently the communists knew they were there. Ooi further wrote that a surrendered Malay communist had come up to him and asked what they had been doing in the jungle near Bentong, Pahang, with a Gurkha patrol. “He and his men were waiting to ambush the Gurkhas when he saw us following the Gurkhas in thick jungle with film camera and still camera. He thought we were from Hollywood, so did not shoot…”1

Ooi also had to worry about being shot by the British. “Once I was sent to the jungle to study the morale of British troops. Those young soldiers were scared stiff when they entered a rubber estate. One of them tripped over a wire and set off an alarm in a hill. The soldiers ran up the hill firing like mad and so we had to run with them or else we might be fired upon by both sides… Those were dangerous years for me and two of my cameramen colleagues. I should have got an OBE [The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire] for that.”2

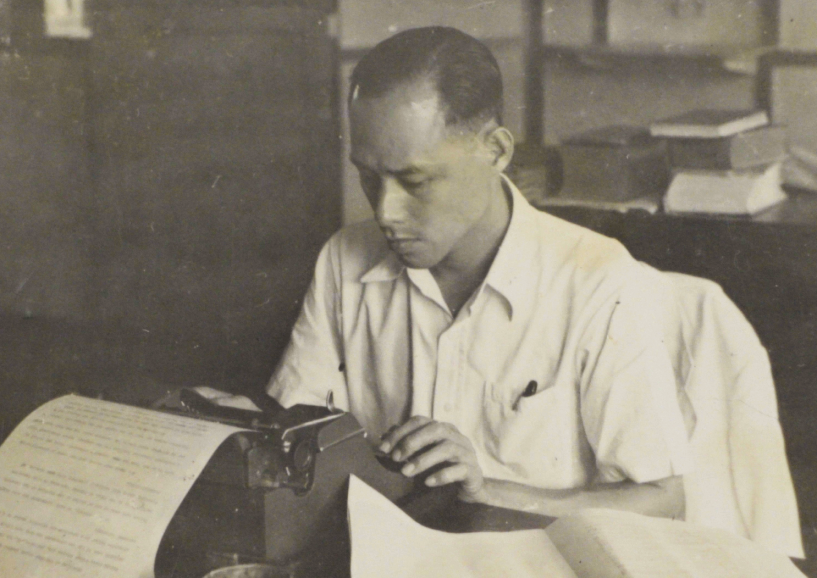

R.B. Ooi, born Ooi Chor Hooi (1905–72), was my maternal grandfather. He was one of the earliest local Malayan journalists writing in English and had worked for newspapers ranging from the Straits Echo to the Malayan Times. In 2023, Irene Lim – his daughter and my mother – donated his personal papers and photos to the National Library of Singapore. These are now held in the R.B. Ooi and Edna Kung Collection. His writings give us a window into discourses – such as multiculturalism and the Malayan identity – that publicly preoccupied the English-educated in the colonial and immediate post-colonial periods in Singapore and Malaysia.

Career in Journalism

Ooi started out as a junior reporter for the Penang-based newspaper, Straits Echo, in 1923. He was the first Chinese reporter among other Ceylonese-Eurasian, British and Australian staff. In 1924, he joined the Treasury in Kuala Lumpur as a clerk. Between 1929 and 1933, Ooi worked as an assistant secretary at the Pontianak Gold Mine, which was owned by his father-in-law, Kung Tian Siong (1876–1958). He then went on to work for Duncan Roberts, managing the International Correspondence Schools at 10 Collyer Quay in Singapore. Ooi also moonlighted as a part-time reporter for the Straits Echo from 1923–28, and the Malaya Tribune from 1934–42, under the penname R.B. Ooi.

In 1942, the family left Singapore for Bukit Mertajam in Province Wellesley (now Seberang Prai), Malaysia, having been informed by Ooi’s “Malay journalist friend” (possibly Yusof Ishak, who later became the first president of Singapore in 1965) that he was on a death blacklist for anti-Japanese articles he had published before the Japanese Occupation (1942–45).3 A year later, Ooi got a job at Juru Rubber Estate in Province Wellesley, an experience that provided much material for his later articles on “life in the ulu” (ulu referring to remote wild places).

Returning to Singapore after the war, Ooi became chief reporter, then sub-editor and columnist for the Malaya Tribune (1945–49). He later worked for the Information Department in Kuala Lumpur as a press officer in 1949 (until 1954) during the Malayan Emergency.

From 1954–58, Ooi was the editor-in-chief of the Singapore Standard. He rejoined the Information Department in 1958 and was appointed head of the press and liaison sections in May 1960. He was subsequently editor-in-chief of the Malayan Times (1962–65) and later the Eastern Sun in Singapore (1966–68).

After his stint at the Eastern Sun, Ooi became a freelance writer (penning a regular column titled “Impromptu” for the Straits Echo) and broadcaster (hosting a monthly current affairs radio talk show called “Window on the World”). In 1968, he received the Ahli Mangku Negara (Defender of the Realm) decoration from the Yang di-Pertuan Agong of Malaysia. Ooi’s last column was published in the Straits Echo shortly after his death in Kuala Lumpur in December 1972.

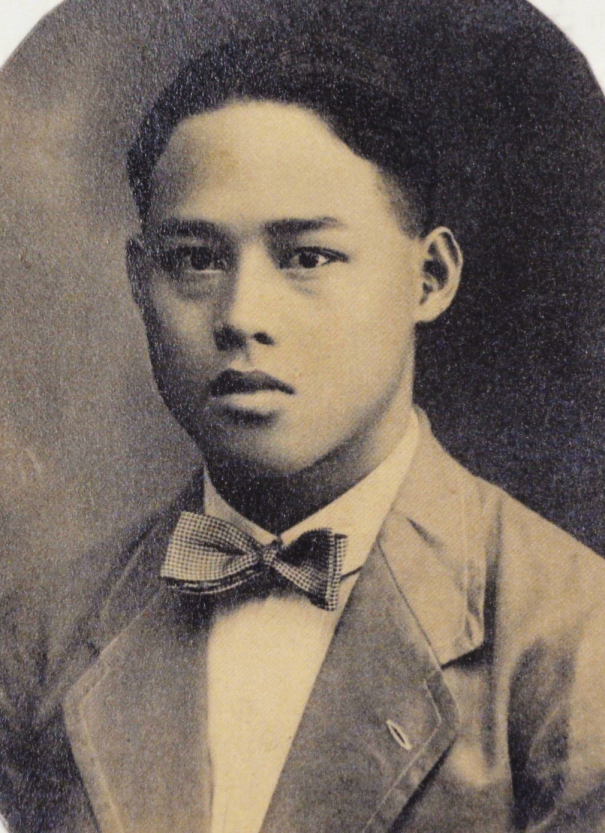

Early Life

Ooi was born and raised in Bukit Mertajam on a coconut plantation “bigger than Singapore” established by his great-grandfather Ooi Tung Kheng, an immigrant from China who was one of the founders of Bukit Mertajam.4 Ooi attended a Methodist primary school and studied at the Anglo-Chinese School (ACS) on Penang Island for his secondary education. He would catch the 4.30 am mail train from Singapore to Prai every morning, then the ferry to Georgetown, before cycling to school. He won a scholarship after topping a state-wide exam.

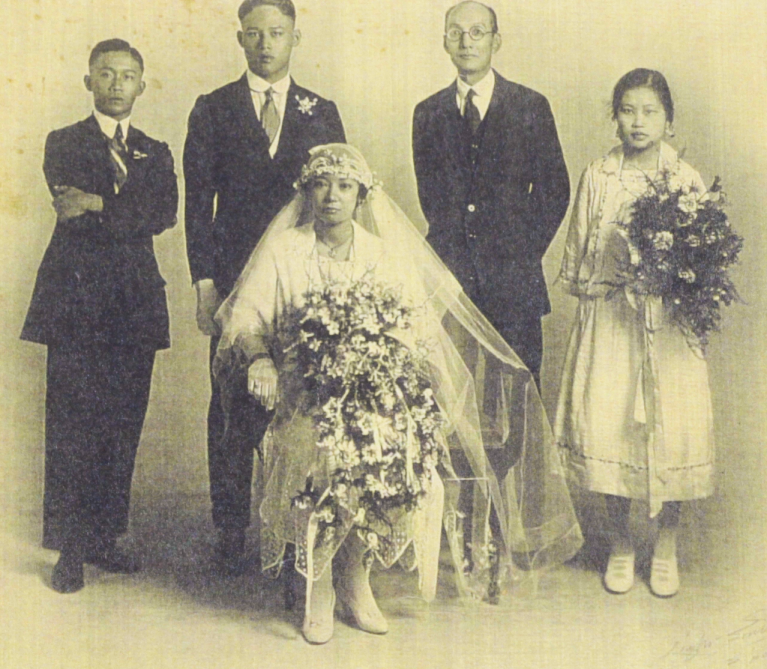

On 15 September 1925, Ooi spotted Edna Kung Gek Neo (1910–2003) on the train. Struck by her beauty, he noted down her name and address from her luggage tag and wrote to her father proposing marriage. Finding out that the Ooi family were educated wealthy landowners, Edna’s father, Kung Tian Siong, a Singapore businessman and direct descendant of Confucius,5 agreed. The Kungs were Christian, so Ooi was baptised for the wedding held at the Wesley Church in Singapore on 5 December 1925, when he was 19 and Edna 15.

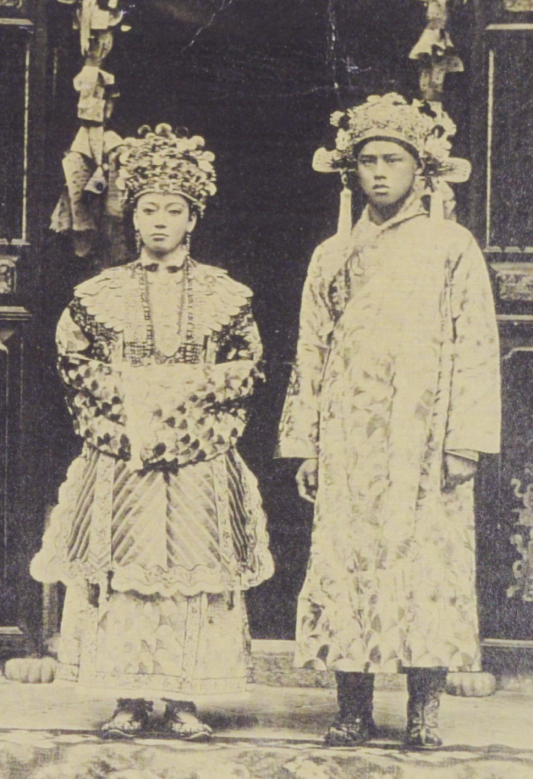

To fulfil his mother’s wishes, Ooi and Edna had a second wedding in Bukit Mertajam according to Chinese rites. They had four children: Irene (born in 1927 in Kuala Lumpur), Violet (1932), Eric (1934) and Sylvia (1936), the latter three were born in Singapore following the family’s move there. Unfortunately, the marriage broke down. My grandmother, Edna, remarried towards the end of the war while my grandfather did not.

Being Malayan

In his writings, which can be seen in the papers donated, Ooi would, sometimes uneasily, inhabit and navigate the British colonial/Western world and the Peranakan (that is, Malay-influenced) Chinese traditional culture into which he had been born and raised.

His writings reveal a man who was a proudly self-conscious Straits Chinese, embodying the three strands of their history and identity – Chinese, Malay and British/Western. Ooi wrote about many aspects of Straits Chinese life and culture. In “The Babas and Nonyas”,6 he recounted the incorporation of Malay music, drama, dance, religion and food into Peranakan culture. He noted that the babas (Peranakan men are known as baba, while the women are known as nonya) supported Malay opera and keroncong music competitions, described their “religious liberalism” as they worshipped at Malay shrines while seeking help from Thai bomohs (shamans), and praised their “innovative genius” in being able to adapt and learn from various cultures.

Ooi was also a passionate advocate of what we would today call multiculturalism, which he saw as a necessary foundation for unity and progress in Malaysia. In 1941, Ooi wrote in the Malaya Tribune that “[t]he Straits Chinese, through their long association with Malays understand the Malays better than new arrivals from China… [who] do not know their language and seldom mix with them”.7

Thirty years later, in 1972, he wrote that the “Malayan Chinese must cultivate a Malayan consciousness and consider themselves people of this country and of nowhere else… the Straits Chinese or Babas endorsed this view because they considered themselves assimilated or integrated Malayans”.8

Western Influence

However, Ooi was also critical of the Straits Chinese for their British affectations, political apathy and class snobbery. “It is the Chinese from the fourth generation onwards who are more British than the British and they are to be found in the Colony of Singapore and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca,” he wrote in the Singapore Standard in 1954.9

He was particularly critical of foreign-educated university graduates, whom he felt “[could not] adjust themselves to their home environments… at this juncture many Malayan graduates feel that their own indigenous cultures are far inferior to what they have acquired in western countries… They were loud in their complaints that Malaya was an uncivilised and uncultured country, because they could not indulge in the fripperies of modern living”.10

In 1948, in the Malaya Tribune, Ooi called Westerners out for their ignorance of Malaya, their sense of superiority, snobbery and racial prejudice, which led to discrimination of locals:

“The British have been administering Malaya for over a century, yet the people in Britain know very little about Malaya… The stories with British heroes subtly preached the superiority of the ‘orang puteh’ in every imaginable situation… Now with snobbery returning to Singapore, some Europeans here…are daily becoming more ‘snooty’… Let them be more human, more friendly, and forget their colour, and they will find Asians more friendly to them.”11

As much as Ooi was critical of Western attitudes and some Westernised Asians, he expressed in the Straits Echo in 1972 that he did not support the erasure of place names and other markers of Malaysia’s colonial heritage. He wrote: “New histories are being written in [Asia and Africa to] rub out former colonial influences. Histories can be written to suit the new people in power, but previous historical influences are embedded deep in the subconscious minds of the people. Their cultures, religions, languages and social customs will contain earmarks of the waves of civilisations that had washed over them in the course of centuries.”12

Curtailing Press Freedom

Ooi was a consummate newspaperman and believed that freedom of the press was essential.13 He had spent most of his journalistic career in Singapore and believed that the independence of Singapore’s newspapers was being eroded.

He revealed in an interview that during his two-year tenure at the Eastern Sun between 1966 and 1968, he had experienced run-ins with then Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. Lee had “on several occasions, in front of all the other editors in Singapore (he called us up as a group very often), accused me of being an MCA [Malaysian Chinese Association] or UMNO [United Malays National Organisation] spy. Also, he often sent his political commissars to our office to see what we were doing, PAP [People’s Action Party] agents were put on our staff and morale was very low”.14 This was one of the major reasons why Ooi subsequently left Singapore in 1968 and moved to Kuala Lumpur.

In that same interview, Ooi described 1971 as a “disastrous year” for journalism in Singapore. That was the year Lee had shut down the Eastern Sun and the Singapore Herald, and also jailed the owner and editors of the Nanyang Siang Pau Chinese newspaper without trial. In an unpublished 1971 manuscript about the history of English-language newspapers in Malaya, Ooi attributed Lee’s actions to his suspicions that the press was “being financed by foreign interests to gain control of Singapore… [w]hatever his bogeys are, the press in Singapore is a docile and commercial one controlled by him”.15

In a 1972 commentary in the Straits Echo, Ooi called for newspapers in Singapore and Malaysia to be separated. “If Singapore does not want foreign capital in and foreign control of its newspapers, why should Malaysia allow Singapore capital to control Malaysian newspapers?” he argued. “Malaysia should have her own independent Press.”16

Ooi also frequently, both in private and in public, railed against the insularity and parochialism of Singaporeans. “Though Singapore claims to be a metropolis, yet the average Singaporean is more parochial than village folks… While Singapore has made economic progress, it has lost its soul. Money is the god Singapore worships.”17

Family, Culture and Nation

Ooi’s writings reflect the issues he cared most about – culture, identity, ethnicity, language, education and race relations – which are still salient today in both Singapore and Malaysia. Though still contentious in societal terms, the national and familial contexts are more positive than what Ooi had come to believe towards the end of his life.

Ooi’s descendants have fared well. His grandchildren and great-grandchildren in Malaysia have married across ethnicities and cultures and are fluent in multiple languages. Several of them, mostly women, did their undergraduate studies in England in engineering, law, accountancy and economics, and all returned home (to Malaysia) thereafter. English remains the dominant family language, as are Western attire, music and other “cultural” habits.

I’m sure my grandfather would be pleased that scholarly research on Straits Chinese history and culture is flourishing today, and that there has been a revival of Straits Chinese arts and culture in both Singapore and Malaysia, with thriving Peranakan associations, cuisine, performing arts and literature. Explorations of local history and “heritage” that formed such a large part of his writing have become popular, even entrenched, in both countries.

As a teenager in Singapore, I wanted to be a writer and corresponded with my grandfather who lived in Malaysia at the time. Education had always been important to him, and he wanted his daughter, Irene, to go to university, which the Second World War and familial disruptions had sadly rendered impossible. Despite his antipathy to foreign university education and academics, he was very proud when I went to Cambridge University as an undergraduate, then the pinnacle of British colonial academic aspirations, and later to Yale.

I think he would have been pleased to learn of my own inclinations towards writing popular commentaries on current affairs, which were published in newspapers like the Straits Times when I was doing my PhD. These include pieces challenging the status quo (in my case, primarily on economic policy, but also on race, inequality and East-West tensions), which could be considered the kind of “political writing” he had done.

In my retirement, I co-founded and co-edit an academic blog promoting scholarship “of, for and by Singapore”, which also advocates for academic freedom.18 In Singapore in 2017, I gave a keynote speech at my alma mater, Methodist Girls’ School, closely tracking my grandfather’s own arguments for multiculturalism, but for the 21st century. This was years before I read his work.19 To paraphrase a popular saying, the durian does not fall far from the tree.

Donated in 2023 by Mrs Irene Lim, daughter of R.B. Ooi, the more than 300 items in the collection include typescripts of Ooi’s articles, which cover a range of topics besides the economic, social and political situation in the region.

Other highlights are his articles for the Foreign News Service such as “The New Nation of Malaysia” (c.1962); an unpublished article, “The English Press of Malaysia and Singapore” (1971); scripts for Radio Malaysia, including one for “Window on the World” about the death of former Indonesian president Sukarno; and personal letters and photographs.

Materials from the collection can be viewed at Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library via online reservation from the third quarter of 2024.

Linda Lim is a Singaporean economist and Professor Emerita of corporate strategy and international business at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business. She also served as director of the University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

Linda Lim is a Singaporean economist and Professor Emerita of corporate strategy and international business at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business. She also served as director of the University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies.Notes

-

Excerpt from letter from R.B. Ooi to his daughter Irene Lim dated 21 November 1969. The letter is among the materials donated by Lim to the National Library of Singapore for the R.B. Ooi and Edna Kung Collection. For more on Lim’s life, see Irene Lim, 90 Years in Singapore (Singapore: Pagesetters Services Pte Ltd., 2020). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 307.7609595 LIM). An excerpt from this memoir was published as Irene Lim, “Asthma, Amahs and Amazing Food,” BiblioAsia 16, no. 4 (January–March 2021): 64–68. ↩

-

Excerpt of letter from R.B. Ooi to Irene Lim, 21 November 1969. ↩

-

For example, a column ranted that “the Japanese are the last people on earth to treat you like human beings once you are under their yoke”. See R.B. Ooi, “Plain Talk to the People,” Malaya Tribune, 10 January 1942, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Braved the Pioneering Days in Malaya: Death of Madam Saw Kim Lian At Age of 90,” Straits Times 18 November 1933, 6; Ooi Chor Hooi, “Life in the Coconut Groves,” Straits Times Annual, 1 January 1939, 16–17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Linda Y.C. Lim, Four Chinese Families in British Colonial Malaya – Confucius, Christianity and Revolution, 4th ed. (Singapore: Blurb, 2019), https://www.blurb.com/b/5022666-four-chinese-families-in-british-colonial-malaya-c. ↩

-

“The Babas and Nonyas,” Parts 1, 2, 3, manuscript c. 1970–72. ↩

-

R.B. Ooi, “Through Chinese Eyes,” Malaya Tribune, 19 April 1941, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“How to Think Malaysian,” Straits Echo, 16 October 1972. (Microfilm NL7162) ↩

-

R.B. Ooi, “A Drop of Ink,” Singapore Standard, 5 June 1954, 6. (From NewspaperSG). This article is mainly a scathing review of U.S. Supreme Court Justice (later Chief Justice) William O. Douglas’ 1953 book, North from Malaya. Douglas wrote the book after a whirlwind British-escorted tour of Malaya and it was full of hilarious errors. See William O. Douglas, North from Malaya (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1953). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959 DOU-[RFL]) ↩

-

R.B. Ooi, “A Drop of Ink,” Singapore Standard, 2 June 1954, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Snobbery Again in Malaya,” Malaya Tribune, 8 August 1948. (Microfilm NL2147) ↩

-

“Can History Be Scrubbed Off?” Straits Echo, 7 December 1972. (Microfilm NL7252) ↩

-

Ooi first wrote about this with respect to Emergency regulations. See R.B. Ooi, “A Drop of Ink,” Singapore Standard, 21 May 1954, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Interview cited in John A. Lent, “Protecting the People,” Index on Censorship 4, no. 3 (1975): 8, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03064227508532443. ↩

-

R.B. Ooi, “The Press of Malaysia and Singapore,” Manuscript, November 1971. ↩

-

“The Press on a Tight-Rope,” Straits Echo, 3 July 1972. (Microfilm NL7126) ↩

-

“The Regimented Singaporean,” Straits Echo, 16 January 1972. (Microfilm NL6974) ↩

-

“About Us,” Academia SG, https://www.academia.sg/about/. ↩

-

Linda Lim, “Singapore and the World: Looking Back and Looking Ahead,” The Online Citizen, 4 June 2017, https://www.theonlinecitizen.com/2017/06/04/singapore-and-the-world-looking-back-and-looking-ahead/. ↩