Laws of Our Land: Foundations of a New Nation

The Singapore Citizenship Ordinance (1957), the Women’s Charter (1961) and the Employment Act (1968) are three important pieces of legislation that have shaped modern Singapore.

By Kevin Khoo, Mark Wong and Fiona Tan

Not so long ago, the identity and legal status of Singapore citizens did not exist, wives in Singapore were not treated as equal partners in marriage, and Singapore’s archaic employment laws were unsuited for a modern industrial economy. But these changed with the introduction of three laws which are featured in a refreshed exhibition by the National Library Board (NLB).

The Singapore Citizenship Ordinance (1957), the Women’s Charter (1961) and the Employment Act (1968) are showcased in “Laws of Our Land: Foundations of a New Nation”. The exhibition, which opened to the public on 5 July 2024, is hosted at the National Gallery Singapore, in the former Chief Justice’s Chamber and Office at the Supreme Court Wing.

Featuring 37 artefacts and reproductions, mainly from the collections of the National Archives of Singapore, National Library and Supreme Court Singapore, the exhibition examines the antecedents and significance of these three landmark legislations at the founding of independent Singapore. By examining the origins of these laws, the exhibition illuminates a pivotal period in Singapore’s nation-building history, highlighting the country’s transition from a British Crown colony to an independent and sovereign nation.

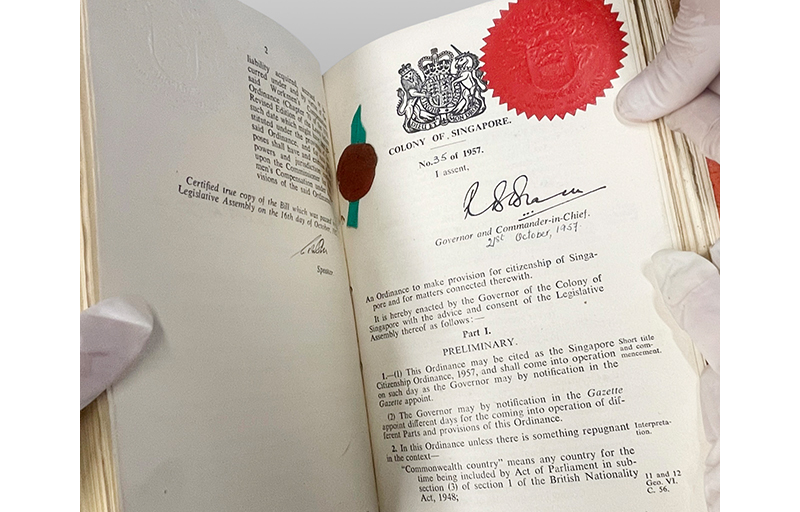

The Singapore Citizenship Ordinance (1957)

The Singapore Citizenship Ordinance of 1957 had its roots in the mid-19th century when the British first introduced nationality laws to Singapore that allowed migrants to be naturalised as British subjects, and for people born in British territories – such as Singapore – to automatically become British citizens regardless of ethnicity. This laid the ground for a multiethnic society to settle and develop in Singapore.

The ordinance introduced the legal status of Singapore citizens. Being a British colony, Singapore’s settled population was split between the local born who were mostly Asian, British subjects and long-staying immigrants who were citizens of other countries.

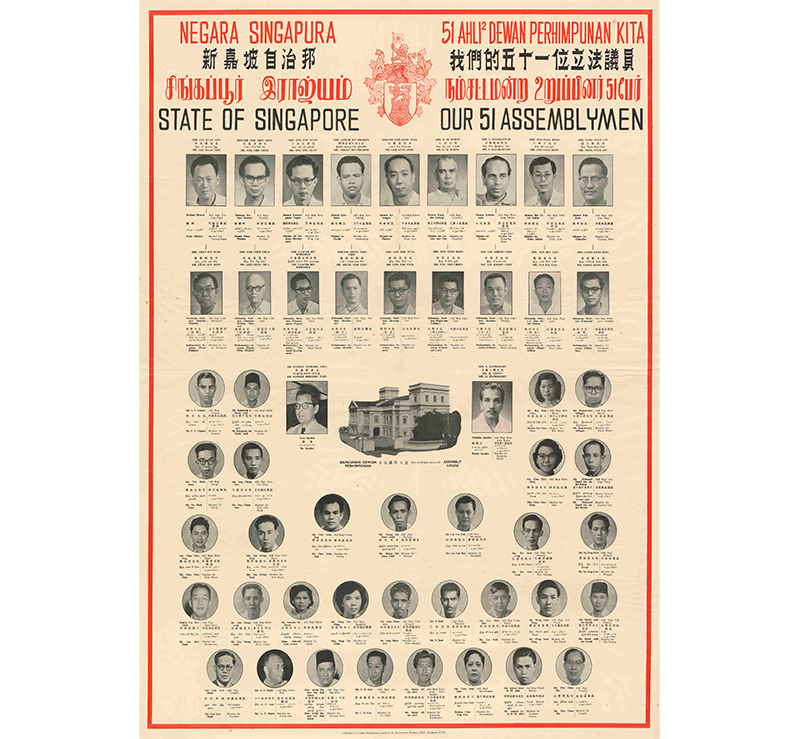

While a Singaporean identity had developed over time, it was not conceived as a political identity requiring Singapore citizenship until the 1950s. Nonetheless, after the legislation was passed, a large majority of Singapore’s population accepted citizenship, and through doing so, the people pledged allegiance to Singapore for the first time.1

The liberal terms of the ordinance permitted virtually all of Singapore’s large settled, mostly Chinese, migrant population of over 220,000 (representing nearly half the adult working population) to become citizens, granting them legal and political rights – notably, voting rights in Singapore and the right to stay in Singapore – which were previously reserved for British subjects who were generally a more affluent group. The enfranchisement of the immigrants changed Singapore’s politics dramatically by giving a much larger voice and voting influence to Singapore’s workers.2

Additionally, the ordinance recognised that pluralism would be the cornerstone of the identity of Singapore’s citizens. No provisions requiring British naturalisation or proficiency in English or Malay language were imposed on those registering to be Singapore citizens. Singapore’s citizens would pledge a common loyalty, but communities could retain their distinctive cultural identity. Citizenship was also offered equally to both men and women, and there was no property ownership or wealth requirement to qualify for citizenship.3

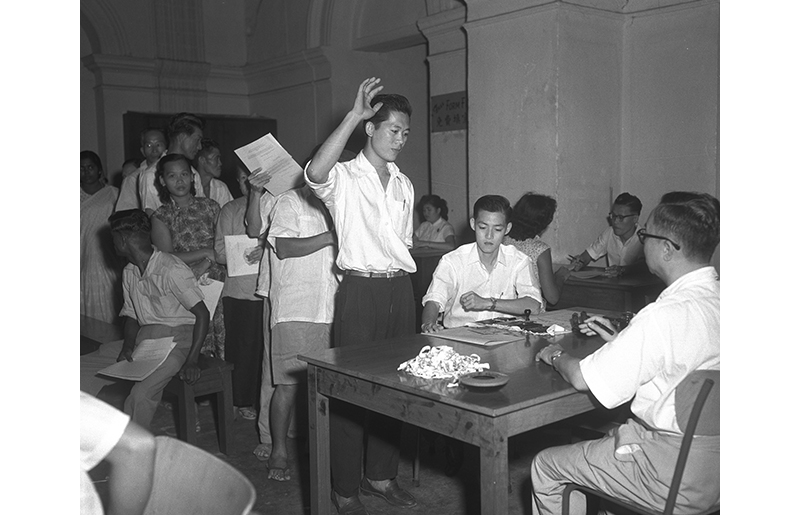

The Singapore Citizenship Ordinance came into force in October 1957, and registration for Singapore citizenship started on 1 November. When the campaign ended on 31 January 1958, more than 320,000 people had registered to be Singapore citizens.4 These new citizens were in addition to some 930,000 local-born persons who were automatically granted Singapore citizenship, out of a population of about 1,446,000.

The ordinance was officially repealed in 1963 and replaced by new citizenship laws under the 1963 State of Singapore Constitution.5

The Women’s Charter (1961)

The Women’s Charter, passed in 1961, was a pioneering legislation that introduced a unitary monogamous law governing civil marriages, and consolidated previous legislation pertaining to the protection of girls and women. It remains the core of non-Muslim family law in Singapore regarding civil marriages, divorces, and spousal and parental responsibilities.6 (Muslim marriages are governed by the Administration of Muslim Law Act 1966.)

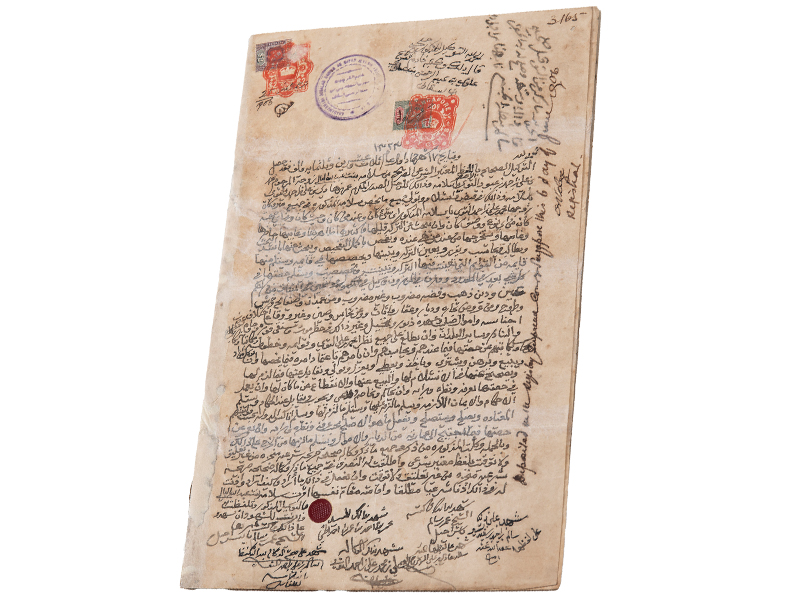

Prior to the introduction of the Women’s Charter, there were diverse marriage practices governed by different laws. These included the Muslim Marriage Ordinance No. 25 of 1957, which had its roots in the Mahomedan Marriage Ordinance No. 5 of 1880; the Christian Marriage Ordinance No. 10 of 1940, which could be traced back to Ordinance No. 3 of 1880; and the Civil Marriage Ordinance No. 9 of 1940.7

However, all these preceding legislations addressed specific types of marriages where registration was not mandatory. This led to uncertainty in matters of inheritance and maintenance in cases of divorce, and colonial judges had to navigate between local customs and colonial law when such disputes were brought to the courts.

In the 1950s, there were increasing calls from the public for greater protection of women, the wider participation of women in public spheres, as well as the enactment of a monogamous marriage law. These efforts were largely led by the Singapore Council of Women, and in 1953, the council drafted the Prevention of Bigamous Marriages Bill, which was distributed to the Legislative Assembly.8

However, these efforts faced resistance from the Chinese, Malay and Indian communities who were concerned about the validity of existing polygamous marriages. They also saw the bill as a challenge to the practice adopted by the colonial authorities in avoiding interference with local customs and religious laws. It was only when the People’s Action Party came into power in 1959 that a legislation for monogamous marriages became possible.9

The introduction of the Women’s Charter Bill in the Legislative Assembly in March 1960 had the support of both the ruling party and opposition members.10 However, specific clauses in the bill were debated intensely in the Assembly and the bill passed through two Select Committees and some redrafting before the act came into force on 15 September 1961.11

While the clauses relating to marriages in the Women’s Charter did not apply to Muslim marriages, which were governed by Muslim law, the increased public debates on protecting women’s welfare in polygamous marriages also led to gradual reforms. These included the establishment of a Syariah Court in 1958, which was empowered to settle disputes relating to Muslim marriages, divorces, separation and payment of alimony. The Muslims (Amendment) Ordinance, 1960 (No. 40 of 1960) required a man who sought to marry another wife to seek the Chief Kathi’s consent.12

Further protection for Muslim women came in the Administration of Muslim Law Act of 1966, which gave women the right to demand maintenance from their husbands even in irrevocable divorces.13

In addition to being a foundational law governing non-Muslim marriages, the Women’s Charter also incorporated other pre-existing laws that covered the protection of women and girls. These had a long and varied legislative history, tracing back to the Women and Girls’ Protection Ordinance of 1887, which had been introduced by the colonial authorities to regulate prostitution and trading of underaged girls.14

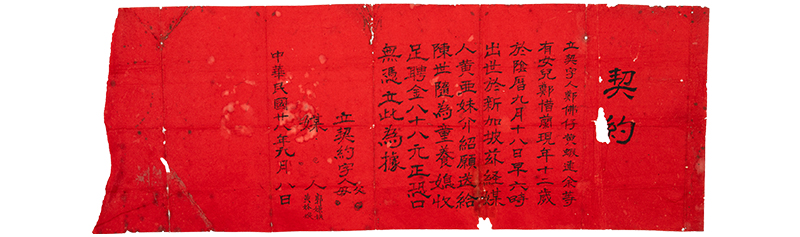

Some of the displays in the exhibition highlight such laws targeted at the protection of girls and women. These include the 1932 Mui Tsai Ordinance that prohibited the buying of young Chinese girls as domestic servants, known as mui-tsai, or “little sister” in Cantonese.15

As the only legislation in Singapore statutes that has the word “Charter” in its title, the Women’s Charter symbolised the new nation’s commitment to gender equality. It has undergone numerous amendments over the decades, with the latest amendment taking effect on 1 July 2024, allowing divorce by mutual agreement.

The Employment Act (1968)

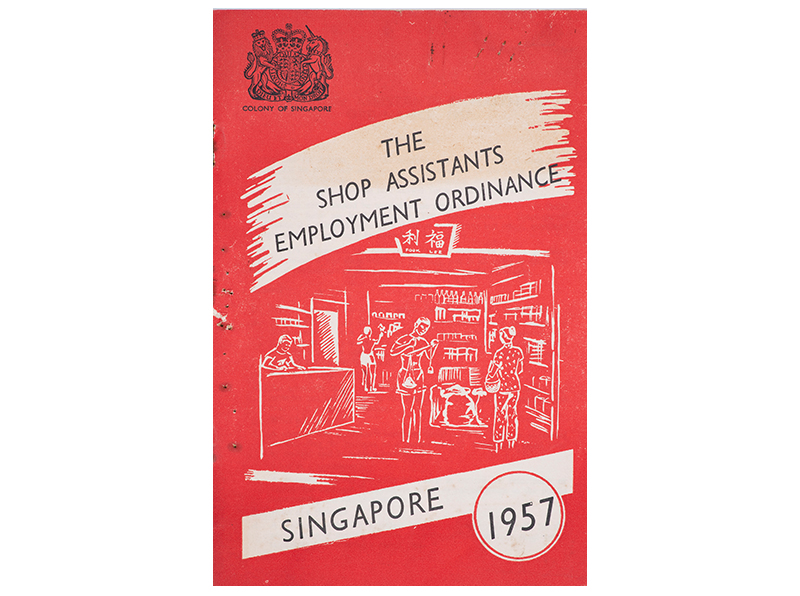

The Employment Act, which came into force on 15 August 1968, modernised Singapore’s labour laws to meet the needs of the new industrial economy and remains Singapore’s main labour law regulating the basic terms and working conditions for employees today. It consolidated various labour laws and served as the basis of employer-employee relations in the newly independent nation. The act also standardised the terms of employment of workers in Singapore across different trades and industries.

After the British East India Company established a trading post in Singapore in 1819, many people from the region – initially, mainly young men – came to Singapore in search of work opportunities. They arrived as indentured labourers, or coolies, recruited through agents in their home countries. Because of the upfront costs to travel here – transport, agent fees, and consumables like food and lodging – they began their journey in debt.

Many labourers were deceived about their work terms and were mistreated. Work conditions were harsh, living conditions were deplorable, and they faced exploitation and even violence. This situation required state intervention, and labour laws were enacted to regulate and protect workers. Over time, many different labour laws were created.

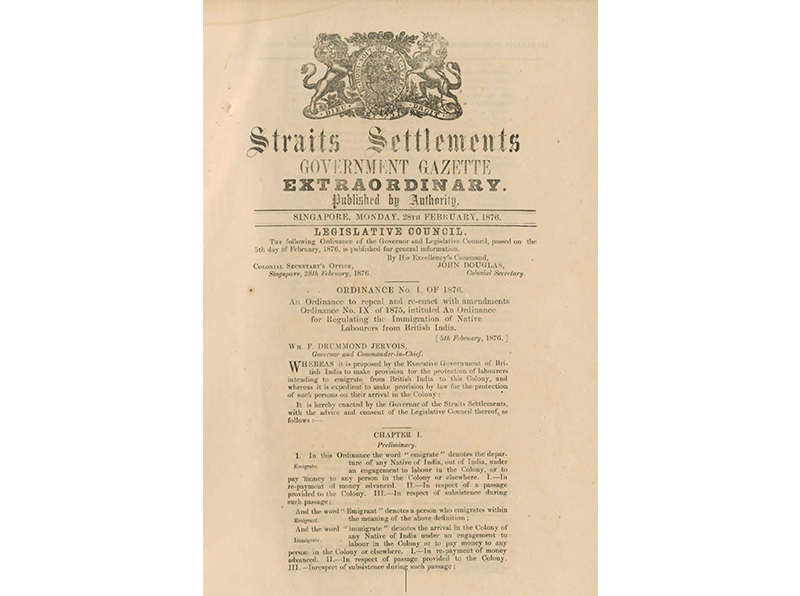

The early laws were specific to different ethnic communities. The Indian Immigrants’ Protection Ordinance of 1876 dealt only with Indian workers. This law allowed Indian migrants below 45 years old and in good health to come here for work. Similarly, the Chinese Immigrants Ordinance of 1877 sought to regulate and protect Chinese immigrants through the establishment of the Chinese Protectorate.16 The legislation also required Chinese immigrants to land at designated ports and depots where they were screened to ensure their fare had been paid. Following this, an official would examine the terms of any labour agreements the immigrant had made before they were allowed to leave the depot.

The Trade Unions Ordinance of 1940 formalised the establishment of trade unions, with the aim to foster better relations between employers and employees.17 The labour movement, intertwined with political shifts, gained momentum after the Japanese Occupation, with unions advocating for both workers’ rights and political causes.

The Employment Act was introduced to respond to specific challenges faced by the new nation. The biggest factor was the economic fallout from the planned British military withdrawal in 1971, which would place at least 21,000 local jobs at stake and lead to an estimated $450 million (around 14 percent of gross domestic product) loss in annual spending by British military personnel.18

Another factor was the toll on the economy resulting from frequent strikes starting from the 1950s. In 1961 alone, there were 116 recorded strikes involving 43,584 workers and causing the loss of 410,889 workdays.19

With the Employment Act, the government aimed to balance employer and employee rights. Employees enjoyed standardised work conditions like fixed working hours, rest days and holidays, while employers were protected by the reduction of excessive overtime claims. Despite criticisms at the time, the act fostered industrial harmony and supported Singapore’s economic growth. Between 1968 and 1972, Singapore’s gross domestic product grew by an average of 13.4 percent.20

The Employment Act has since undergone a number of revisions and amendments, with the most recent 2020 Revised Edition taking effect on 31 December 2021.

The collections of the National Archives of Singapore and National Library originate from government and authoritative sources. The curators – Kevin Khoo, Mark Wong and Fiona Tan – were mindful to present a balanced narrative, and to include personal documents like marriage certificates and identity cards, as well as oral history interviews and audiovisual recordings, so that people’s voices and personal stories could be heard. In addition to physical displays, the exhibition features several multimedia interactives, including augmented reality experiences, where visitors can interact with composite characters inspired by historical sources.

The exhibition will enable visitors to develop a new appreciation for Singapore’s legal history, and take a deeper dive into the topic by perusing other related materials at the National Archives and National Library.

Kevin Khoo is an Assistant Director/Senior Archivist (Documentation) with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore. His responsibilities include documenting and contextualising the oral history collection, archival research and content development.

Kevin Khoo is an Assistant Director/Senior Archivist (Documentation) with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore. His responsibilities include documenting and contextualising the oral history collection, archival research and content development.  Mark Wong is an Assistant Director/Senior Specialist (Oral History) with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore, where he leads oral history projects on Singapore’s political developments and experiences with COVID-19. He is a Council Member and Regional Representative (Asia) of the International Oral History Association.

Mark Wong is an Assistant Director/Senior Specialist (Oral History) with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore, where he leads oral history projects on Singapore’s political developments and experiences with COVID-19. He is a Council Member and Regional Representative (Asia) of the International Oral History Association.  Fiona Tan was formerly a Senior Archivist (Records Management) with the National Archives of Singapore. She was part of the team that advises government agencies on records management, facilitating the processes of transfer, digitisation and access of government records transferred to the National Archives of Singapore. She is presently on secondment to the Ministry of Digital Development and Information.

Fiona Tan was formerly a Senior Archivist (Records Management) with the National Archives of Singapore. She was part of the team that advises government agencies on records management, facilitating the processes of transfer, digitisation and access of government records transferred to the National Archives of Singapore. She is presently on secondment to the Ministry of Digital Development and Information. Notes

-

Low Choo Chin, Report on Citizenship Law in Malaysia and Singapore (Italy: Global Citizenship Observatory, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, 2017), 1–15, https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2106108.html. ↩

-

C.M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2017), 268. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR) ↩

-

Yeo Kim Wah, Political Development in Singapore, 1945–1955 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1973), 135–72. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

“Citizenship Bill Approved by the Assembly,” Straits Times, 17 October 1957, 1; “321,453 New Citizens,” Straits Times, 2 February 1958, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

S.C. Chua, Report on the Census of Population 1957 (Singapore: Department of Statistics, Government Printer, 1964), 43, 46. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

“The New Women’s Charter,” Straits Times, 23 March 1961, 16; “One Man One Wife,” Straits Times, 25 March 1961, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ann Wee, “The Women’s Charter, 1961: Where We Were Coming From and How We Got There,” in Singapore Women’s Charter: Roles and Responsibilities and Rights in Marriage, ed. Theresa W. Devasahayam. (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2011) 44–45. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.42095957 SIN) ↩

-

Phyllis Chew, “Blazing a Trail: The Fight for Women’s Rights in Singapore,” BiblioAsia 14, no. 3 (October–December 2018): 32–37. ↩

-

Chew, “Blazing a Trail”; “We Have Created a New Awakening in Malaya,” Straits Times, 11 July 1959, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leong Wai Kum, “Fifty Years and More of the ‘Women’s Charter’ of Singapore,” Singapore Journal of Legal Studies (July 2008): 4. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Evelyn Tu, “Women’s Charter,” Straits Times, 14 September 1961, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Bill Makes Muslims Happy,” Straits Times, 8 October 1956, 7. (From NewspaperSG); M. Siraj, “The Syariah Court of Singapore and Its Control of the Divorce Rate,” Malaya Law Review 5, no. 1 (July 1963): 154. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

M. Siraj, “Recent Changes in the Administration of Muslim Family Law in Malaysia and Singapore,” International and Comparative Law Quarterly 17, no. 1 (January 1968): 228. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Pinang Gazette. Tuesday, 11th January, 1887,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 11 January 1887, 6. (From NewspaerSG) ↩

-

“Abolition of Mui Tsai,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 27 January 1932, 10; “The Mui Tsai Reform,” Straits Times, 6 February 1932, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Ordinances Enacted by the Governor of the Straits Settlements with the Advice and Consent of the Legislative Council Thereof in the Year… (Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office, 1877), 6–8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 348.5957 SGGAS-HWE]) ↩

-

“Trade Unionism in Malaya,” Malaya Tribune, 21 October 1941, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pull-Out in Middle 1970’s,” Straits Times, 19 July 1967, 1; “All Out by 1971,” Straits Times, 17 January 1968, 1 (From NewspaperSG); Parliament of Singapore, First Session of the Second Parliament, vol. 27 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 15 July 1968, col. 647, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=004_19680715_S0002_T0002. ↩

-

“Only 14 Strikes in S’pore–The Lowest Ever,” Straits Times, 5 January 1967, 7; “Strikes Here Fizzle Out,” New Nation, 19 March 1975, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

World Bank Group, “GDP Growth (Annual %) – Singapore,” accessed 12 July 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=1972&locations=SG&start=1968. ↩