Chingay in the 19th and 20th Centuries: A Community Procession in Time

The Chingay Parade held annually in Singapore during the Lunar New Year has its roots in the tai ge from China.

By Timothy Pwee

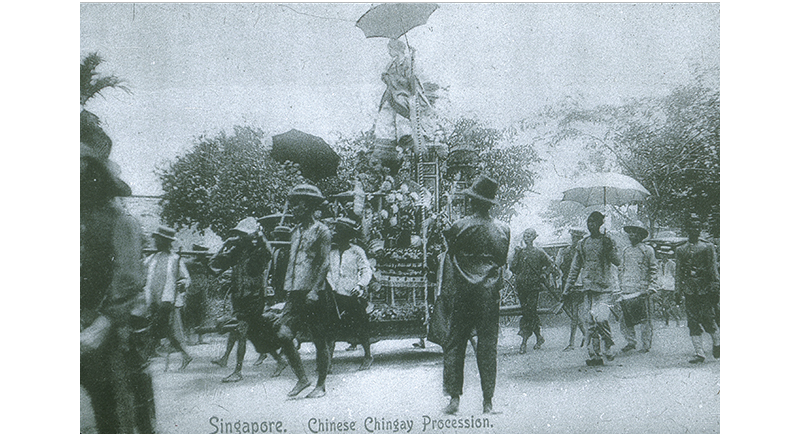

Most people in Singapore today associate the Chingay Parade with the Lunar New Year, which is not surprising because since the early 1970s, the People’s Association has been organising the annual Chingay Parade to celebrate the new year.

However, chingay originally had nothing to do with the Lunar New Year. According to Carstairs Douglas, who was a missionary in Amoy (now Xiamen) for more than 20 years, chingay or tsng gē in Hokkien, is derived from the Chinese term, 裝藝 (zhuang yi). In his 1873 Chinese-English Amoy dictionary, Carstairs Douglas says the gē (藝) is “a large frame with incense and boys dressed as girls carried in processions”, and tsng (裝) refers to the children dressed up as characters on that mobile stage to form a tableaux.1 (A colleague pointed out that Douglas may have meant the traditional Chinese character 妝 [妆; meaning to adorn or to dress up] rather than 裝 [装; meaning dress or attire]. Although they are two different words, both have the same pronunciation in Hokkien, Cantonese and Mandarin.)

Tai Ge Processions

The procession of dressed-up children held aloft on poles or on platforms is more commonly known as 抬阁 (tai ge) in China, and is frequently seen in various festival processions across the country (抬 meaning “carry”).

A well-known tai ge takes place annually at Hong Kong’s Cheung Chau Bun Festival in the fourth lunar month (April–May) called 飄色 (piu sik in Cantonese or “floating” colours). There is also a reference to tai ge by the famous author Lu Xun (1881–1936) in a collection of essays about his childhood in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, where he grew up at the end of the 19th century.2

However, an 1868 account by the American Presbyterian missionary John Livingston Nevius of the processions in Ningpo near Shanghai suggests that those being held aloft were not children. He wrote: “On a platform borne on men’s shoulders is seen a beautiful and finely-dressed female (it is hardly necessary to say that these are not of a very respectable class), and another one, standing tiptoe on the uplifted hand of the first, is elevated high in air, a very conspicuous object, and much admired and commented upon.”3

Several municipalities across China have listed tai ge as part of their local heritage. These processions were held for different reasons and at different times of the year to honour deities, as prayers for safety and security (祈安), or for thanksgiving purposes. It would be safe to say that tai ge was an activity that could be part of festive processions like lion or dragon dances.

The earliest tai ge procession in Singapore is possibly the one held in 1840 to welcome the statue of Mazu (Goddess of the Sea) to the Thian Hock Keng temple. The Singapore Free Press and Daily Advertiser reported on 23 April 1840:

“But what particularly engaged the attention of spectators, and was the chief feature of the procession, was the little girls from 5 to 8 years age, carried aloft in groups on gayly ornamented platforms, and dressed in every variety of Tartar and Chinese costume. The little creatures were supported in their place by iron rods, or some such contrivance, which were concealed under their clothes, and their infant charms were shewn off to the greatest advantage by the rich and peculiar dresses in which they were arrayed – every care being taken to shield them from the effects of the sun’s rays, which shone out in full brightness during the whole time the procession lasted.”4

This Hokkien chingay seemed to have developed into an event held every three years, with processions in the 10th and 12th lunar months. The initial procession would take place in the 10th lunar month (generally November in the Gregorian calendar) followed by a return procession in the 12th month (typically in January).

In the 2006 book about Thian Hock Keng, The Guardian of the South Seas, there is an excellent description of the 1901 procession inviting the Tua Pek Kong (大伯公) of Heng San Ting, Guangze Zunwang (广泽尊王) of Hong San See and Qingshui Zushi (清水祖师) of Kim Lan Beo (all Hokkien temples) to Thian Hock Keng for Chinese opera on the 8th day of the 10th lunar month and the return to their respective temples on the 4th day of the 12th lunar month:

“The invitational procession began from the back of the Thian Hock Keng, and followed a designated route to the sounds of drums and gongs to Heng San Ting on Silat Road, Hong San See on Peck Seah Street, and Kim Lan Beo Temple on Narcis Street to pick up the three deities. After being ‘guests’ for nearly two months at the Thian Hock Keng, the three gods were escorted back to their temples… The various representatives of the five streets prepared pavilions, drums and gongs, cavalry, and flags to enliven the atmosphere. There were lion dances as well. Groups also acted out various characters in folk tales such as The Eight Immortals Crossing the Ocean, Flooding of Jinshan Temple, and Wang Zhaojun’s Mission to the Frontier.”5

Rival Chingay Processions

The Thian Hock Keng processions appeared to have been overshadowed in the latter part of the 19th century by a larger annual chingay organised by a coalition of other Chinese dialect communities (Teochew, Cantonese, Hainanese and Hakka) centred around the temple on Phillip Street, the Wak Hai Cheng Bio (粤海清庙). This chingay took place at around the same time at the end of each year.

Lim How Seng discusses this rivalry in his chapter, “Social Structure and Bang Interactions”, published in the 2019 A General History of the Chinese in Singapore. He points to the various non-Hokkien bang (帮), or mutual aid communities centred around dialect lines, forming a “united front” as a strategy to “counter the over-powering Hokkien bang”. The objective of forming such an alliance was to maintain a balance of power in bang politics.6 Congratulatory plaques for major events were installed in Teochew, Cantonese, Hainanese and Hakka temples but not in Hokkien temples.

The press picked up on the procession’s role as a uniting mechanism. In November 1897, the Mid-Day Herald and Daily Advertiser observed:

“The occasion has been termed ‘chingay day,’ in rough parlance, but otherwise it is known as the celebration attending the removal of one patron saint from one temple to another. It consists of usual feasting and rejoicing, and organising a huge procession through the town. It is said moreover, to be a cementing of old friendships, the patching up of those little disaffections which usually accompany caste differences in the East. It is the meeting of the clans, and a time when the Teochews, Kehs, Cantonese and Hylams, assemble together and congratulate each other.”7

It is also one of those occasions where “processional cars” were first used, as described by the Straits Times Weekly Issue in 1887: “The procession was fortunate in getting magnificent weather, and there was no fear of rain coming down, so that the most gorgeous of silk banners and silk embroidered dresses and splendid processional cars were brought out to enhance the grandeur of the procession.”8 In this context, “cars” meant a wheeled vehicle. (The first motor car arrived in Singapore only in 1896,9 and the contraction of “motor car” to just “car” happened much later when the motor car became an everyday occurrence.)

In the early 20th century, Hokkien modernist reformers felt that the large sums of money used for chingay processions and Sembayang Hantu (Seventh Month Prayers) were better deployed elsewhere, such as for educational purposes.10 As a result, public subscriptions to fund the Thian Hock Keng chingay ended and the procession was limited to just one carriage for the Tua Pek Kong, meaning that there would no longer be any accompanying processional chingay carriages.11 Thian Hock Keng finally ended the procession in 1935.

The “united front” chingay procession also seemed to have ceased at around the same time. By the 1930s, chingay had become a thing of the past according to temple histories. Other reasons for the cessation of Singapore’s chingay could be the lessening of the divide between the Hokkiens and other Chinese dialect groups as well as the growing inconvenience of stopping the tram system, the banks and the port for the long procession to pass.

Penang: Chingay Capital

Singapore is not the only city in the region to have chingay. Johor Bahru’s Chingay Festival is held at the end of the Lunar New Year from the 20th to the 22nd of the first lunar month (正月二十至卄二日), which culminates in a night procession. Centred around the downtown Johor Old Temple (柔佛古廟), it brings the Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka and Hainanese communities together. However, it is Penang that is arguably more famous for chingay.

The earliest chingay in Penang is likely a procession for the reopening of the Kong Hock Keong (广福宫) temple on Pitt Street in December 1862. It was first reported by the Pinang Argus on 1 January 1863 and republished in the Singapore Free Press on 29 January. The paper wrote:

“The strange spectacle, so wild and fantastic to the European imagination, was curious in the extreme, and was, no doubt, immediately relished by the Celestial portion of the spectators, familiar with the meaning of the motley groups – perhaps a mile in length – that paraded the streets with a dreadful din of gongs, trumpets and crackers. Doubtless each tableau, rendered so charming to the eye by a diversity of brightly coloured habiliments and flaunting pennants, had some occult significance, but why… poor little children were perched dangling… and forced to remain there for hours in one fixed position.”12

By the last decade of the 19th century, there appeared to be several different processions in Penang. In September 1883, the Straits Times Weekly Issue reported on the Poh Choo Siah-Tua Pek Kong procession that attracted the Chinese from the whole of the Straits as well as Burma and Sumatra. Described as a procession “on a scale of magnificence hitherto unequalled”, it had “36 stages or platforms in the shape of an immense centipede – 15 ornamental stages containing paper dolls and animals representing theatrical scenes, fish and fruit lanterns”.13 (This was a form of tai ge still seen in Taiwan today. It is apparently a variant of the chingay called the 蜈蚣阵, or “centipede parade”.)

A Hokkien chingay was reported in February 1890 as happening at the end of the Lunar New Year.14 In March 1897, there was news of a chingay held annually for the “Tohpekong” from the temple on King Street15 (廣東大伯公街; Kuin-Tang Tua Pek Kong Kay) by the Hakka and the Cantonese. This latter procession, taking place on the 15th and 16th days of the second lunar month, featured “groups of beautiful girls and boys perched aloft on flowery cars known as ‘chingay’”.16

The Penang Chinese even organised chingay processions as part of colonial celebrations such as Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, Prince Arthur of Connaught’s visit in 1906 and the 1911 coronation of King George V. Not to be left out, Singapore’s Chinese community met and agreed in early 1911 to organise a chingay for King George V’s coronation, but when the official programme for Singapore came out, there was no chingay. Instead, Singapore had a children’s festival, races, fireworks and lanterns.17

Interestingly, the 1911 Penang Chingay for the coronation served dual purposes. The first two parades on 20 and 22 June were for the coronation and the next two parades on 24 and 26 June were for Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy.18 The latter processions were not regular affairs but held from time to time.

The first procession for Guanyin was in 1900 when it was organised as a thanksgiving for the cessation of the 1899 plague in Penang that caused 39 deaths.19 The second procession was in 1911, while the third procession in honour of the Goddess was in 1919, at the end of World War I. The fourth and final one was in 1928, with the first two days commemorating the reunification of China under the Nanjing government, and the last two days for the revival of trade and industry in Malaya, as well as for good health.20

One of the Penang processions that gradually coalesced into an annual event and continues to this day is a Tua Pek Kong procession held on Chap Goh Meh, the deity’s birthday. On this day, the Tua Pek Kong deity of the Poh Hock Seah Temple (宝福社) in town is transported to Tanjung Tokong’s Sea Pearl Island Tua Peh Kong Temple (海珠屿大伯公庙) for the relighting of the incense. The deity then returns to the Poh Hock Seah Temple the following day.21 Tanjung Tokong is where the first Chinese was supposed to have landed and Poh Hock Seah is the second-oldest temple in Penang.22 Hence the annual procession from the “younger” temple to the “senior” one.

Moving with the Times

Press reports of Penang’s chingay show how these processions have progressed into the 20th century.

Electric lamps made their appearance on the “cars” for musicians in the 1911 coronation procession. It is only at the 1919 thanksgiving processions for the Goddess of Mercy that there was mention of a silver cup being awarded to the “best decorated Ch’ng Peh (ornamental car)”.23 The press reports, unfortunately, did not specify how these chingay “cars” were carried or drawn along. For the Chap Goh Meh Tua Pek Kong procession in 1924, the Straits Echo reported that “[o]nly one section had the Chingay pulled by men; the others were either drawn by bullocks or motor”.24

Photographs of the 1928 Penang chingay were taken by Yeoh Oon Chuan and they appear in the 188th anniversary commemorative publication for the Kong Hock Keong Guanyin temple on Pitt Street.25 While many of the chingay “cars” were mounted on motor vehicles, some appeared to be hand-drawn.

Although chingay “cars” were organised around deities and temples, these were not necessarily religious in nature. Aside from tableaux depicting stories of deities, the Penang chingay featured scenes from wayang (Chinese operas) and Chinese legends as well.

Chingay processions were also used as an advertising medium, as the Pinang Gazette and Daily Chronicle observed of the 1924 procession: “On one of the banners we saw the name of Messrs. Wearne Brothers and their advertisement of the Ford Cars. This was more conspicuous in the United Merchants’ section where could be seen several advertisements of milk, brandy, flour, etc.”26

As the years went by, people became more creative with their chingay “cars”. In the 1927 procession, there was even a “car” dressed up in a Hollywood theme. “A silver cup was presented in Penang for the beautiful car in the Chingay procession, which carried a boy and a girl, dressed as the late Rudolph Valentino, as they appeared in the film, ‘The Sheik of Araby’,” the Straits Echo reported.27

This did not go down well with some. A strongly worded editorial by the Singapore Free Press noted that “there is an increasing tendency amongst the many races forming our town communities to discard their picturesque national costumes and customs and take to those of the West”. Although the paper added that the Penang chingay was to be admired and respected, but “even here we find that the award goes to a Chinese boy and girl dressed up as Valentino and Agnes Ayres from one of those erotic tales of imaginary passion invented by some Western film producer!”28

While the traditional chingay of the 19th and 20th centuries has its roots in the tai ge from China where dressed-up children are held aloft on poles or platforms, the Chingay Parade we are familiar with today – a stage mounted on a motor vehicle with dressed actors comfortably displayed within – is similar to the Western idea of parade floats.

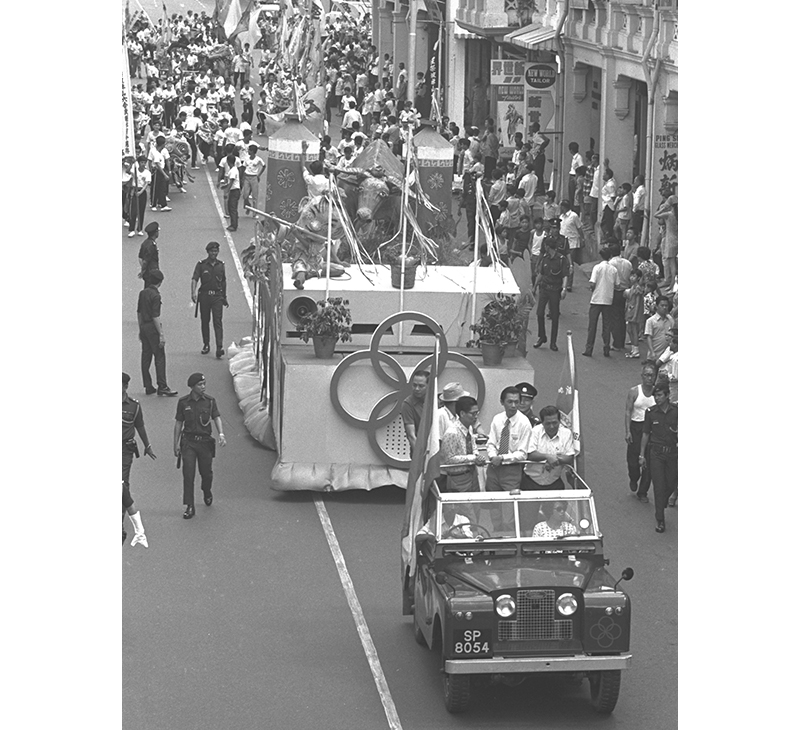

After firecrackers were banned in 1972,29 Lunar New Year celebrations became less lively and boisterous. Being familiar with the annual Penang chingay, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who was also chairman of the People’s Association, suggested holding a similar chingay to enliven new year festivities.30

The first Chingay Parade with the float procession as we know it was staged on 4 February 1973.31 The parade has been held annually since then, evolving over the years into a multicultural event involving participants of different ethnicities and nationalities.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His interests range from Singapore’s business and natural history to its daily life and religion. These are among the areas he is developing the library’s collections in.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His interests range from Singapore’s business and natural history to its daily life and religion. These are among the areas he is developing the library’s collections in. Notes

-

Carstairs Douglas, Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy, with the Principal Variations of the Chang-Chew and Chin-Chew Dialects (London: Trubner, 1873), 104–105, 579. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 495.17321 DOU-[LYF]) [Hokkien is a variety of the Southern Min language spoken in the coastal region of southeastern Fujian, China.] ↩

-

Lu Xun, 朝花夕拾= Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk, trans. Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2000), 79. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. C814.3 LX) (eBook editions are available on NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

John Livingston Nevius, China and the Chinese: A General Description of the Country and Its Inhabitants (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1869), 267, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/chinaandchinese00nevigoog. ↩

-

“Chinese Processions,” Singapore Free Press and Daily Advertiser, 23 April 1840, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Guardian of the South Seas: Thian Hock Keng and the Hokkien Huay Kuan (Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 2006), 42. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 369.25957 GUA) ↩

-

Lim How Seng, “Social Structure and Bang Interactions,” in A General History of the Chinese in Singapore ed. Kwa Chong Guan and Kua Bak Lim (Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations & World Scientific, 2019), 122. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.895105957 GEN) ↩

-

“A Huge Chinese Procession,” Mid-Day Herald and Daily Advertiser, 22 November 1897, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Great Annual Religious Procession,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 19 December 1887, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore’s First Autocar,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 13 August 1896, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Chinese Reform,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 18 December 1906, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pinang,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 29 January 1863, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Penang News,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 20 September 1883, 1; “News of the Week,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 20 September 1883, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Local and General,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 4 February 1890, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Local and General,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 17 March 1897, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Second Moon Festivals,” Straits Echo, 30 March 1904, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Further Festivities,” Straits Budget, 29 June 1911, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Coronation Chingay Procession,” Straits Echo Mail Edition, 19 May 1911, 408. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Penang in 1899,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 26 May 1900, 2; “Grand Chingay Procession in Penang,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 5 June 1900, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Chingay Procession in Penang,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 24 August 1928, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jean DeBernardi, Penang: Rites of Belonging in a Malaysian Chinese Community (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009),151–54. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.895105951 DEB) ↩

-

Tan Kim Hong, The Chinese in Penang: A Pictorial History (Penang: Areca Books, 2007), 206. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.51004951 TAN) ↩

-

“Town Decorations,” Straits Echo Mail Edition, 3 July 1911, 537; “Chingay Festival: Recognition of Merit,” Straits Echo Mail Edition, 19 November 1919, 1883. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Chingay: An Impression,” Straits Echo Mail Edition, 26 February 1924, 148. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeoh Oon Chuan, “1928 Procession Pictures”, in 槟榔屿广福宫庆祝建庙188周年暨观音菩萨出游纪念特刊 [Commemorative publication of the 188th anniversary celebration and chingay procession in honour of boddhisatva Guanyin, Kong Hock Keong, Penang]. (Penang: Kong Hock Keong Publishing Department, 1989), 431–63. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 294.3435095951 COM) ↩

-

“Chingay Procession: Imposing Spectacle,” Pinang Gazette and Daily Chronicle, 19 February 1924, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“M.A.P.,” Straits Echo Weekly Edition, 19 February 1927, 155. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Dreary Prospect,” Singapore Free Press, 19 February 1927, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Total Ban on Crackers,” Straits Times, 2 March 1972, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

People’s Association, The People’s Parade: 45 Years of Chingay (Singapore: People’s Association, 2017), 11. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 394.5095957 PEO) ↩

-

“Chingay Parade a Success, So an Encore Is Planned Next Chinese New Year,” Straits Times, 5 April 1973, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩