Japanese Anglicans in World War Two Singapore

During the Japanese Occupation, four Japanese Anglicans were a sign of hope for the locals during a dark chapter in Singapore’s history.

By John Bray

In February 1942, a week after the fall of Singapore, Reverend John B.H. Lee, the vicar of the Holy Trinity Anglican Church on Hamiliton Road, was surprised – and probably more than a little alarmed – to receive a visit from a Japanese military officer.1 The officer, Taka Sakurai (1914–2010), did his best to put the vicar at ease. He explained that he too was an Anglican Christian and that, like Holy Trinity, his home church in Japan was affiliated with a London-based Anglican missionary group, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

A week later, Sakurai returned with another Japanese Anglican officer, Andrew Tokuji Ogawa (1905–2001). The two men said that the vicar need not fear: the churches were to leave their doors open, and services could continue.

In addition to Sakurai and Ogawa, we know of at least two more Japanese Anglicans who were in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation. The third was Reverend Tadashi Matsumoto (1907–66), who arrived in 1943 and served as a military interpreter. A fourth, Chiyokichi Ariga (1895–1987), likewise arrived in 1943, having been released from internment in Canada. He spent the last two years of the war as a civilian teacher in an orphanage in Singapore.

All four men lived through a particularly difficult period of Japanese and Southeast Asian history. In their home country, the mood of the times was intensely nationalistic but many of their friends and teachers were foreigners, and they belonged to a faith whose claims are universal. Although they were relatively junior in rank, they were able to use their influence to ease the difficulties of the churches here at a time of crisis. Their interconnected personal stories offer a distinctive angle on the complexities of life in Japanese-occupied Singapore.

Christian Faith and the Japanese Empire

All four men were members of the Nippon Sei Ko Kai (NSKK; literally the “Holy Catholic Church in Japan”), which became an autonomous church within the Anglican communion in 1887. They had an additional personal connection in that they were all graduates of Rikkyo University – founded in 1874 as St Paul’s School – one of Tokyo’s leading universities today.

In the 1930s, Japanese Christians struggled to determine their response to the political pressures of Japanese nationalism.2 Key issues included the question of how to respond to official demands that the Emperor be respected as a divine figure in accordance with the state-sponsored Shinto religion. Foreign missionaries fell under growing suspicion as a result of the nationalist fervour accompanying the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. In December 1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, Samuel Heaslett (1875–1944), the UK-born Presiding Bishop of the NSKK, was imprisoned on charges of espionage and then deported.

Against this background, Japanese Christians needed to tread carefully lest they be accused of disloyalty. These challenges were all the greater in occupied Singapore.

Lieutenant Andrew Tokuji Ogawa – Director of Education and Religion

As Director of Education and Religion in Singapore, Lieutenant (later Captain) Ogawa was responsible for liaising with the churches. He served in this post for a relatively short period and was posted to Sumatra, Indonesia, in May 1943. However, his initial cooperation with the churches set the tone for the administration’s policy for the duration of the occupation. The churches in Singapore were treated much more favourably than their counterparts elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

Ogawa had been educated at Rikkyo and then earned his master’s degree at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in 1932. After returning to Tokyo, he taught economics at Rikkyo before being drafted into the army.

Once in Singapore, Ogawa soon made contact with the Right Reverend John Leonard Wilson (1897–1970), the Anglican Bishop of Singapore.3 Almost all Europeans in Singapore were interned in the prisoner-of-war camp in Changi. However, Ogawa was able to arrange for Wilson to return to his residence, together with Reverend John Hayter, the Assistant Chaplain at St Andrew’s Cathedral, and Reverend Reginald Keith Sorby Adams of St Andrew’s School. Ogawa also provided Wilson with a Japanese-language pass permitting him to visit Changi for confirmation services to prisoners-of-war. Until March 1943, when they were again interned, these three were the only European Anglican priests to operate freely in Singapore.

They made full use of the opportunity to continue their ministry in the churches and to build up the Asian church leadership in preparation for the time when they might again be detained. Their access to prisoner-of-war camps meant that they were also able to maintain an illicit “postal service” connecting the inmates with civilian detainees held elsewhere on the island.4

Ogawa regularly attended services at St Andrew’s Cathedral. According to Hayter, he and a fellow officer (possibly Sakurai) “made a point of arriving in a military staff car with a blue flag flying”, thus demonstrating by his presence that the cathedral was under military protection.5 Hayter adds that it was “largely due to his persistence that an order was issued that no churches or their compounds should be used for military purposes”.

Ogawa recruited Reverend Dr D.D. Chelliah, a recently ordained Indian priest who had previously been the vice-principal at St Andrew’s School, to serve as his assistant at the Department of Education and Religion.6 Chelliah continued in the same role after Ogawa was replaced by a Mr Watanabe. Chelliah also served as Wilson’s deputy following the latter’s internment in March 1943.

Ogawa, Wilson and Chelliah worked together to establish the Federation of Christian Churches. According to Chelliah, Ogawa wanted to deal with the churches “collectively and not individually”, and the federation was supposed to be the link.7 All the main Protestant churches joined the federation, with Chelliah serving as its president while Wilson was the chairman of the Union Committee.8

The federation’s objectives included representing the needs of the churches to the Japanese authorities, organising relief work and holding combined services. At a “United Service of Christian Witness” held at St Andrew’s Cathedral on Whit Sunday (Pentecost) in May 1942, Ogawa read the lesson in English.9 In an interview published in the Syonan Times on 1 November 1942, Ogawa pointed out that the “ideal of Christian Federation was the call of Jesus Christ to strengthen the churches in the ‘present circumstances’”. He also said that “the work of Western missionaries had ceased, and it was the task and privilege of Oriental leaders to continue their work on their own initiative”.10

The federation was widely regarded as the beginning of ecumenical activity in Singapore. However, Hayter speculated that it might have been “too successful”, noting that the Kempeitai – the much-feared military police of the Imperial Japanese Army – regarded it with great suspicion.11 In March 1943, after Ogawa had been moved to a different post, the Japanese authorities abruptly shut the federation down.

Ogawa might have had his own problems with the Kempeitai. He had become a firm friend of Wilson and the other Anglican clergymen. However, he discontinued his visits to their residence after the Kempeitai had warned him that he was becoming “too friendly”.12

Much later, in an interview with the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1969, Ogawa commented that senior officers were “always eyeing me down and trying to get some[thing] nasty over me”.13 However, he added that there were quite a few friends who had a similar faith in Christ, and they had also helped him.

Lieutenant Taka Sakurai – Military Propaganda Department

One of those friends whom Ogawa mentioned would have been Lieutenant Taka Sakurai. In his role in the Military Propaganda Department, Sakurai had less formal contact with the churches than Ogawa. However, in his personal capacity, he attended services at St Andrew’s Cathedral. Local Christians evidently regarded him as a “friend in high places”, noting his eventual transfer away from Singapore with regret.14

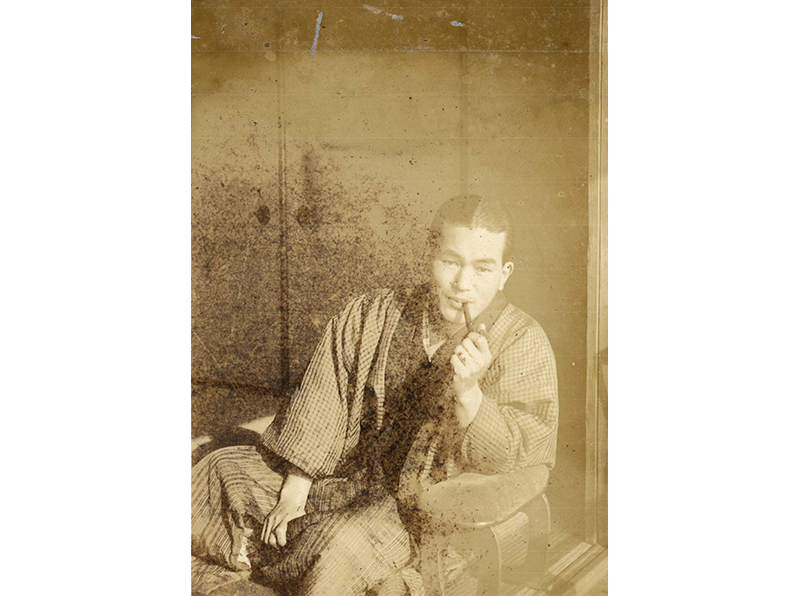

Sakurai was born in Yokosuka, Kanagawa prefecture, in 1914. He became a Christian while in junior high school and discovered a vocation to the priesthood. In June 1938, he graduated from the NSKK seminary, which was affiliated with Rikkyo.15 However, in November that year, he was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army and in early 1942, he was part of the Japanese military expedition that captured Singapore.

Sakurai’s office was on the fifth floor of the Cathay Building (renamed Dai Toa Gekijo; Greater Eastern Asian Theatre), which also housed the Japanese Broadcasting Department and the Military Information Bureau.16 There he met Ogawa for the first time in five years, and they went to the officers’ club to exchange stories. According to Sakurai, there were as many as 15 or 16 Rikkyo graduates in Singapore, perhaps including both Christians and non-Christians, and they later held a reunion dinner.17

In an oral history interview with the National Archives of Singapore in 2006, Sakurai recalled that there had been no other Christians in his unit. When the Syonan Jinja – a Shinto shrine at MacRitchie Reservoir commemorating fallen soldiers who had died in the battles for Malaya and Sumatra – was consecrated, all the other senior officers were given roles to play with the exception of Sakurai, who was exempted as he was a Christian.18

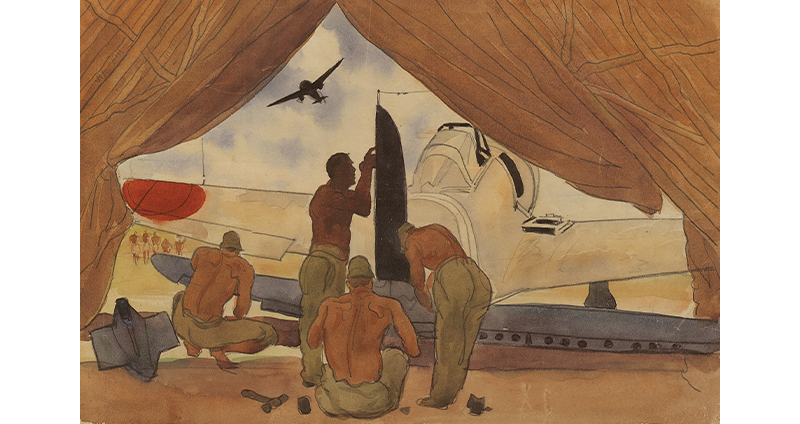

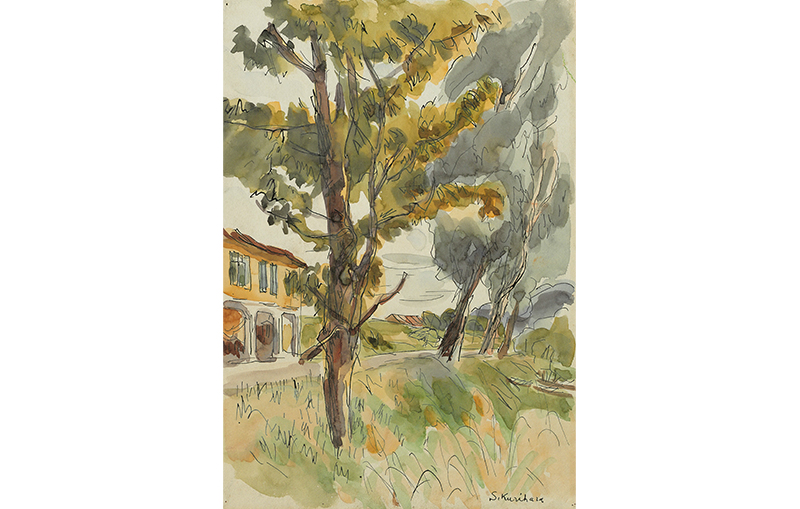

Interestingly, one of Sakurai’s assignments in Singapore was to liaise with five Japanese artists to produce paintings of Singapore. These were Tsuguharu Fujita (1886–1968), Goro Tsuruta (1890–1969), Saburo Miyamoto (1905–74), Kenichi Nakamura (1895–1967) and Shin Kurihara (1894–1966). Sakurai used the paintings to create postcards celebrating Japan’s victory in the war that soldiers could send back home to their families. Sakurai donated the five original drawings as well as postcards to the National Archives in 2006 and the paintings are currently on display at the Former Ford Factory museum in Bukit Timah.19

In 1944, Sakurai was redeployed to the military frontline in the Japanese invasion of northeastern India. By July 1944, the Japanese forces had been defeated at the battles of Imphal and Kohima – which together formed one of the turning points of World War II – and they were forced to retreat into Burma (now Myanmar). By this time, their supply lines were over-extended and soldiers had to rely on their own resources to find their way back to central Burma. Many more died from sickness and starvation than from actual fighting.20

Sakurai himself led a group that struggled to rejoin the main Japanese forces in central Burma.21 Their route led them to the Sittang River at a point where it was some 250 yards (230 m) wide and in full flood because of the rainy season. Shortly before attempting to cross the river on crudely assembled rafts, Sakurai realised that Noguchi, one of his comrades, was missing. Leaving his men at the riverbank, Sakurai went back to look for him but to no avail. As he later recalled, it was his Christian faith that had given him the courage to continue. Finally, Sakurai managed to cross the river as one of the few survivors from his original group.22

Sakurai’s experience in Burma was imprinted in his mind for the rest of his life, underlining his sense of the futility of war. In his will, he asked for some of his ashes to be scattered in the Sittang River after his death.

Reverend Tadashi Matsumoto – Military Interpreter

The third Japanese Anglican, Reverend Tadashi Matsumoto, came to Singapore in 1943. He was fluent in English and was therefore recruited as a military interpreter. In his spare time, he attended church services and did his best to encourage the local Christians whom he encountered.

Matsumoto had graduated from Rikkyo and the NSKK seminary in 1930. He then went to Prince Edward Island in Canada to serve in a church for Japanese migrants, some 500 miles (800 km) north of Vancouver.23 Subsequently, he embarked on postgraduate theological studies, first in Chicago in the United States and then in Toronto in Canada. After returning to Japan, he served in churches in the Narita area and in Kanagawa prefecture before being drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army. On his arrival in Singapore, he contacted Sakurai, having been alerted to his presence by another Anglican priest in Japan.24

One of the churches where Matsumoto worshipped was St Hilda’s in Katong. He developed a close connection with the congregation, but was dismayed at what he regarded as poor attendance at Sunday services. In a letter to Reverend John Hayter, the Assistant Chaplain at St Andrew’s Cathedral, in early 1945, Mrs Doris Maddox, one of the church’s parishioners, wrote: “St Hilda’s had a friend in the Revd. Matsumoto of the Tokio Diocese in Japan. He rounded up those who missed Church, stressed the importance of regularity and was pained to find that all four hundred members did not come every Sunday.”25

She added that Matsumoto had advised Reverend John Handy, the priest in charge of St Hilda’s, “when there were tricky knots to unravel”. This advice evidently included recommendations on how to keep on the right side of the Japanese authorities. Apparently, he had said: “You do not cooperate enough with the Government. You are concerned only with helping people. You must make some gesture towards the Government.”26 St Hilda’s responded with a move that was both diplomatic and humanitarian: the church arranged to give the Good Friday collection to the Japanese Red Cross.

In early 1945, Matsumoto was transferred to Taiping in northern Malaya. After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, he was held in a British internment camp there. During his detention, he met a British army chaplain who gave him the book, Prophets for a Day of Judgement.27 The book was written specifically for a wartime audience and looks for inspiration from four people who had lived through earlier catastrophes: the Prophet Jeremiah (c. 770–c. 650 BCE), Augustine of Hippo (354–430), Julian of Norwich (1343–c. 1416) and the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821–81).

Matsumoto was so impressed by the book that he translated it into Japanese. Of the four, Dostoyevsky was the one who struck him the most. As a young man, Dostoyevsky had been sentenced to death, only to be reprieved at the very last moment. Matsumoto believed that the book held a special message for his fellow prisoners, some of whom were on trial for war crimes. In the foreword of his translated version, Matsumoto wrote that he was able to share the draft with prisoners who had been sentenced to death, and to pray with them before their executions.28

Matsumoto was eventually released from detention and found his way back to Japan where he resumed his career as a parish priest.

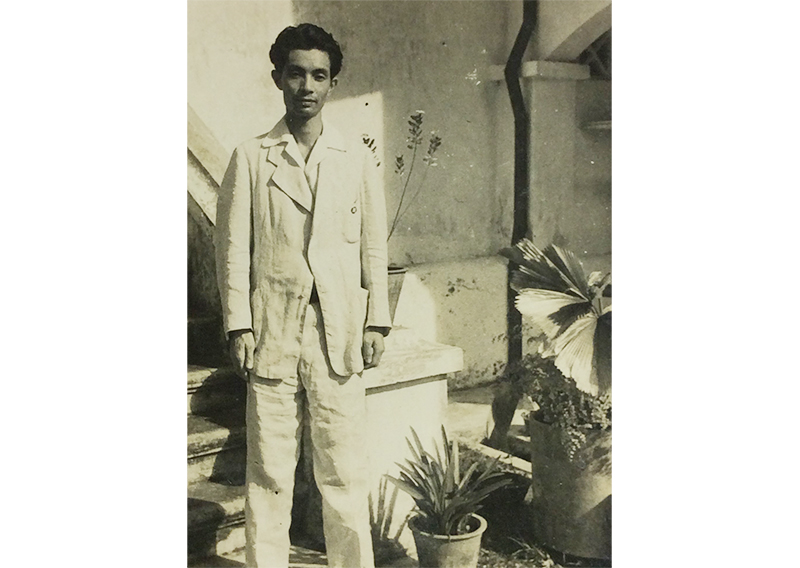

Chiyokichi Ariga – Schoolteacher and Orphanage Warden

Chiyokichi Ariga was the fourth Japanese Anglican in Singapore of whom we have definite knowledge. Unlike the others, he was a civilian rather than a military official. Being part of the same network of Rikkyo alumni, he made contact with Sakurai soon after arriving in Singapore in August 1943.

Ariga had previously worked in Canada, first as a journalist and then as a teacher in a school for children of Japanese migrants. He kept in close contact with both the Canadian and the Japanese branches of the Anglican church, and he had been instrumental in encouraging Matsumoto to go to Canada.29

After the outbreak of war, Ariga was detained in a prisoner-of-war camp in Ontaria.30 However, together with his wife and daughter, he was among a group of Japanese who were repatriated in exchange for Canadian prisoners. They travelled by sea via Mozambique to Singapore. Ariga decided to stay on in Singapore as he believed that there might be more opportunities for Japanese speakers of English. He also felt that the Japanese mainland would be more militaristic.31

According to Ariga’s memoirs, his wife was appointed to head an orphanage at York Hill, whose children included those of foreign detainees. Ariga became a teacher at the orphanage, and the couple worked there together until the end of the war, making a small but important humanitarian contribution in difficult times.32

Postwar Reconstruction in Japan

After the war, all four men contributed to the rebuilding of the NSKK in Japan. Ogawa became a professor in Rikkyo. In 1953, Bishop Wilson invited him to the annual meeting in the UK of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel where he presented on “Christian Work in Japan Today”, noting that there was still a role for foreign missionaries.33

At the end of the presentation, Ogawa briefly commented on his own role in Singapore during the war, stating that he had not done anything beyond what Christians had been taught to do. “I certainly did not want to disappoint the prayers that our friends had been offering for our work,” he said. While in Britain, Ogawa joined the crowds outside Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.34 He met Wilson once more when both men returned to Singapore in 1969 for a documentary by the British Broadcasting Corporation on wartime Singapore. Ogawa died in 2001.

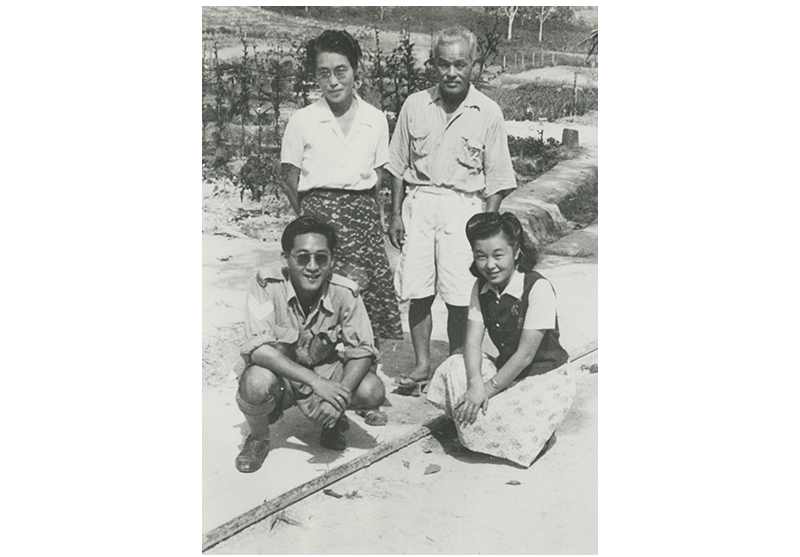

Ariga became the principal of Rikkyo Elementary School, working alongside Sakurai as the chaplain. On a more personal note, Ariga introduced Sakurai to Matsumoto’s sister Fusae, and they got married in 1948. In retirement, Ariga returned to North America.

Matsumoto returned to parish ministry at St Mary’s Church in Ichikawa, Chiba prefecture, while also serving as a lecturer in the NSKK’s Central Theological College in Tokyo. He died in 1966, aged 58.

After nearly a decade’s interruption, Sakurai was able to return to his original vocation: he was ordained as a deacon in 1947 and became a priest the following year. He then served as a chaplain to the Rikkyo Elementary School, which was associated with Rikkyo University. One of his contributions was arranging for Singapore basketball teams to play in Japan.35

Sakurai visited Singapore for the last time in 2006. He had learnt of the opening of Memories at Old Ford Factory, an exhibition about the Japanese Occupation (now the Former Ford Factory). He decided to donate the paintings by the five war artists he had worked with to the National Archives of Singapore. Sakurai also gave an oral history interview where he talked about the donation and his time in Singapore during the war.36 Sakurai concluded by saying that he loved Singapore and was glad that he had had an opportunity to live here. He was only sad that it was the war that had brought him here.

In Japan, I am grateful for the support of Jean Ogawa (Andrew Tokuji Ogawa’s daughter), Mrs Hiroko Ito (Tadashi Matsumoto’s youngest daughter), Reverend Isao Uematsu (nephew to both Tadashi Matsumoto and Taka Sakurai), Hidekazu Miyagawa and Masaaki Miyamoto (Rikkyo University Archives), and Thomas Takao Nagai (Church of the Resurrection, Chiba).

Yusuke Tanaka helped with background information on the Japanese in Canada. My wife Miyoko Kobayashi provided linguistic and much other support throughout.

Dr John Bray is a risk consultant and policy specialist currently based in Singapore. He has a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge and has published a number of academic research articles on the history of Christianity in the Himalayan border regions of northern India. He is a former member of the St Andrew’s Cathedral Heritage Committee.

Dr John Bray is a risk consultant and policy specialist currently based in Singapore. He has a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge and has published a number of academic research articles on the history of Christianity in the Himalayan border regions of northern India. He is a former member of the St Andrew’s Cathedral Heritage Committee. Notes

-

Diocese of Singapore, Report for the Period from 1941 to 1949 (Singapore: Diocesan Synod of Singapore, 1951). I thank Sharon Lim for sharing this source. ↩

-

A. Hamish Ion, “The Cross Under an Imperial Sun: Imperialism, Nationalism, and Japanese Christianity,” in Handbook of Christianity in Japan, ed. Mark R. Mullins (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 69–100, https://brill.com/edcollbook/title/8295. ↩

-

See John Leonard Wilson’s Biography: Roy McKay, John Leonard Wilson: Confessor of the Faith (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1973), 19–24. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 283.0924 WIL.M) ↩

-

McKay, John Leonard Wilson, 24–25. ↩

-

John Hayter, Priest in Prison: Four Years of Life in a Japanese-occupied Singapore (Worthing: Churchman Publishing, 1989), 86. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.547252092 HAY-[JSB]) ↩

-

D.D. Chelliah, oral history interview by Lim Yoon Lin, 1973, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Japanese Occupation Project (accession no. OH_1973_002), 2n. ↩

-

D.D. Chelliah, interview, 1973, 2n. ↩

-

Joseph Thambiah, Providence in Adversity: World War 2 and the Anglican Church in Singapore (Singapore: Joseph Thambiah, 2022), 82. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 283.5957 THA) ↩

-

Thambiah, Providence in Adversity, 83. ↩

-

“Christian Bodies Must Abandon Dependence on Missionaries,” Syonan Times, 1 November 1942, 4. (From NewspaperSG). The Syonan Times or Syonan Shimbun was produced on the presses of the Straits Times during the Japanese Occupation. The name of the paper varied during the occupation. ↩

-

Hayter, Priest in Prison, 77. ↩

-

Hayter, Priest in Prison, 85. ↩

-

“Return to Hell,” BBC, 1969. The clip where Ogawa makes this comment is included in the St Andrew’s Cathedral Unity of Faith video. ↩

-

Diocese of Singapore, Report for the Period from 1941 to 1949, 21. ↩

-

The biographical details come from the postscript to: Taka Sakurai, Biruma Sensen to Watashi [Burmese Frontline and I] (Tokyo: Shugengaisa Sei Ko Kai Shuppan, 2012) ↩

-

Taka Sakurai, “Hito-wa Shinko Naku Shite Ikirarenai” [“We cannot live without faith” based on an interview with Mr/Ms Asada, 29 January 2003.]. Nakama: Rikkyo Shogakko Dosokai 50-shunen kinenshi 1954–2003 [Rikkyo Primary School Alumni 50th anniversary commemorative magazine: 2003]. ↩

-

Sakurai, “Hito-wa Shinko Naku Shite Ikirarenai.” ↩

-

Taka Sakurai, oral history interview by Stella Wee, 30 June 2006, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 3, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003068), 9–10, 13. ↩

-

Taka Sakurai, oral history interview by Claire Yeo, 30 June 2006, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 3, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003068), 61–74. ↩

-

Kohei Mororama, et al., Victory into Defeat: Japan’s Disastrous Road to Burma (Myanmar) and India, trans. Myanma Ahthan Kyaw Oo, H. Tanabe and Tin Hlaing. (Yangon: Thu Ri Ya Publishing House, 2007), 152–54. ↩

-

Sakurai, Biruma Sensen to Watashi. ↩

-

Sakurai, Biruma Sensen to Watashi. ↩

-

For accounts of the Anglican Church of Canada’s Japanese-language churches, see Patricia E. Roy, “An Ambiguous Relationship: Anglicans and the Japanese in British Columbia, 1902–1949,” BC Studies, no. 192 (Winter 2016–2017): 105–24. (From ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website); Timothy M. Nakayama, “Anglican Missions to the Japanese in Canada,” Journal of the Canadian Church Historical Society 8, no. 1 (June 1966, rev. ed. 2003): 26–88, https://anglicanhistory.org/academic/nakayama2003.pdf. ↩

-

Sakurai, “Hito-wa Shinko Naku Shite Ikirarenai.” ↩

-

Hayter, Priest in Prison, 267. ↩

-

Hayter, Priest in Prison, 267. ↩

-

Albert Edward Baker, Prophets for a Day of Judgment, with an Introduction by the Archbishop of Canterbury (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1944). ↩

-

Tadashi Matsumoto, Kunan No Yogensha: Dosutoehusukii Sonota (Tokyo: Shunkosha, 1949). ↩

-

Chiyokichi Ariga wrote several books, including a biography of a Canadian missionary which was translated into English in 1998. See Chiyokichi Ariga, The Rev. Frank Cassillis-Kennedy: Elder to the Japanese Canadians, Japanese Canadian Christian Churches Historical Project. (Scarborough, Ontario: Japanese Canadian Christian Churches Historical Project, 1998) ↩

-

Yusuke Tanaka, “80 Years Since the Internment of Japanese Canadians. Part 1: How the Nikkei Were Dragged into War,” Discover Nikkei, 25 April 2002, https://discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2022/4/25/japanese-canadajin-80-1/; Yusuke Tanaka, “Trans-Pacific Voyage: Kawabata Family’s 125 Years – Part 2,” Nikkei Images 22, no. 2 (2017), 19–23, https://centre.nikkeiplace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/NI2017_Vol22No02_Web.pdf. ↩

-

Chiyokichi Ariga, Rokkī No Yūwaku [“Temptation of the Rockies”] (Tokyo: n.p., 1952), 171–72; Sakurai, “Hito-wa Shinko Naku Shite Ikirarenai.” ↩

-

Ariga, Rokkī No Yūwaku, 171–72; Sakurai, “Hito-wa Shinko Naku Shite Ikirarenai.” ↩

-

Tokuji Ogawa, “Christian Work in Japan Today,” 1953, typescript. (From Rikkyo University Archives) ↩

-

Typescript article (in English) by Tokuji Ogawa, Rikkyo Echo, 4 June 1953. (From Rikkyo University Archives) ↩

-

Correspondence with Reverend Isao Uematsu (Sakurai’s nephew), April 2022. ↩

-

Taka Sakurai, oral history interview, 30 June 2006, Reel/Disc 3, 69–74. ↩