Cups and Sources: Hunting Down the Origins of Kueh Pie Tee

Kueh pie tee is a fixture of classic Singaporean cooking, yet its identity has the shape of an enigma, filled with mystery and garnished with riddles.

By Christopher Tan

When I was growing up, family parties were often graced with kueh pie tee – crispy batter cups filled with savoury braised bangkuang (yambean or jicama), and garnished with toppings and sauces. Like many others, we called them “top hats” for their resemblance to Fred Astaire’s famous headgear.1 This Western nickname, plus the fact that “pie tee” has no meaning in any local dialect, always made me wonder about its heritage.

Its earliest mention in local media was in the Straits Times on 7 March 1954. “‘Pie tee’… consists of bits of meat and vegetable packed in a tiny pastry cup and bathed in two delicate sauces. Once you start eating, you can’t stop,” wrote Francis Wong, covering a fundraising food fair at Wesley Methodist Church.2 The quote marks and description are telling – was the dish then still unfamiliar to the average reader?

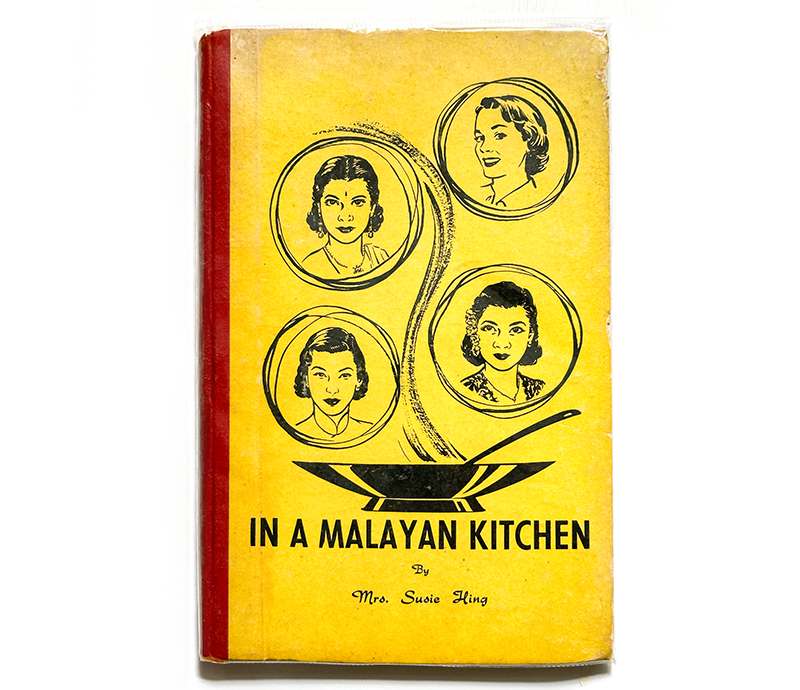

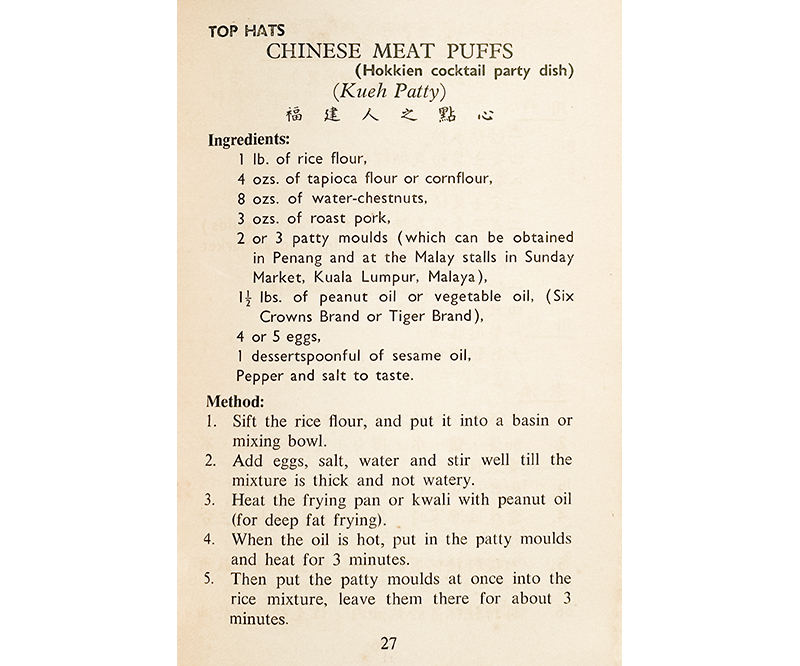

Its name was certainly not yet standardised – variant spellings like “paitee”, “pieti” and “paiti” appeared in local media until well into the 2000s – but one particular variant was common. Susie Hing’s 1956 cookbook, In a Malayan Kitchen, bears her recipe for “Kroket Tjanker (Java Kwei Patti)”.3 Local cooking teacher Chan Sow Lin gave the dish no fewer than four names in her 1960 Chinese Party Book, titling her recipe “Top Hats – Chinese Meat Puffs (Hokkien cocktail party dish) (Kueh Patty)”.4 As late as November 1980, a Straits Times advertisement for C.K. Tang department store featured a “Kueh Patti Maker” costing a princely $4.20.5

As it turns out, this alternative moniker – “patti” or “patty” – is a major clue to kueh pie tee’s origin.

World Cups

The technique of dipping preheated metal moulds in batter and then into hot oil, so that the adhered batter firms up into a defined shape and eventually releases to float free, is both very old and very widespread. Its earliest mention in any cookery text dates to 1570, in chef Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera dell’arte del cucinare.6

In Scappi’s recipe, moulds depicting lions, eagles and “fanciful shapes” are dipped in a batter of flour, water, white wine, oil, salt and saffron, and then into hot oil. A second recipe for a rose-scented goat’s milk batter fried in hot lard includes the pro tip of blotting excess fat off the preheated mould to obtain a shapelier fritter.7

Food scholar Priscilla Mary Işın traces the technique further back, probably more than five centuries, to Turkey. She notes that in Eastern Turkey, families traditionally each possessed unique bespoke iron moulds to make fritters called demir tatlısı.8 The Erzurum region’s blacksmiths were particularly famed for forging them: no other irons “hold the batter like an Erzurum iron” commented one author in 1900.9 That area lies on the Silk Road, along which Işın surmises the recipe and moulds could have spread to the rest of the globe.

They ultimately did so along paths of migration and colonisation as well as trade routes. The Dutch brought them to Norway, India and Southeast Asia, while the Spanish and Portuguese took them to South America, and Scandinavian immigrants introduced them to the United States.

Along the way, flower shapes became the most popular motifs, as seen in many localised fritter names: kueh rose or kuih ros (Singapore and Malaysia), kanom dok jok (Thailand; meaning “lotus flower sweet”), rosettbakkels (Norway; meaning “rose bakes”) and rosette cookies (America).

Cup shapes also evolved, and here is our first link to kueh pie tee: antique krustadjärn fritter irons found in Swedish museums are identical to vintage pie tee moulds in all respects, being heavy fluted round metal cups mounted on steel rods with wooden handles.10

American Pie… Tee?

In the US, such moulds were widely sold from the late 19th century onwards. A basic set typically paired a flower or geometric motif with a cup shape and a removable handle, while fancier sets ranged across a huge variety of decorative shapes. Fannie Farmer’s famous Boston Cooking-School Cookbook features “Swedish timbale irons” with fluted cups in round, oval, heart and diamond shapes.11 Timbale irons later came to be more commonly called “patty irons” or “patty molds”, and the cups they fried up, “patty shells”.

And here is our second link: on 1 April 1958, “The Gourmet Club” column of the Singapore Free Press cited “a kwei patty iron for frying batter”.12 Subsequently, a New Nation eatery review on 19 January 1978 expressly equated Singaporean and American fritters, noting that besides popiah skins, Joo Chiat’s Kway Guan Huat – an 80-year-old business still thriving today – “sells… ‘kway pie tee’ cups (crispy patty shells)”.13

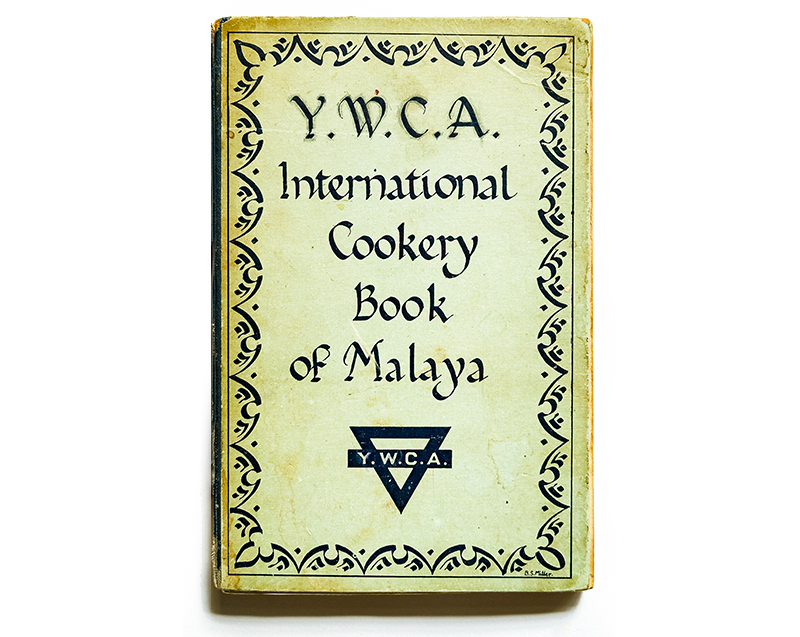

We know that Singapore’s YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association) conducted Western cuisine cookery lessons from at least 1913 onwards.14 The International Cookery Book of Malaya published by the association includes a classic “pattie shell” recipe using eggs, sugar, salt, milk and flour.15

Our local newspapers also featured American-style recipes for patty shell savouries in the 1930s.16 Hence it seems eminently plausible that patty irons came to Singapore via the American expatriate community around the early 1900s, and that “patty” slowly elided to “pie tee” on local tongues. While their fluted pattern remains, the cast iron and aluminium of American moulds were eventually supplanted by the solid brass most common here today.

In a booklet dating back to the 1939 New York World’s Fair published by the Sealtest Kitchen, a food research body serving the US dairy industry, I came across a recipe for “Creamed Shrimp and Peas in Timbale Cases”.17 I was able to source the same vintage patty iron pictured in the recipe photo, forged by American ironware firm Griswold. Once cleaned of rust, it flawlessly turned out pretty fluted heart cups with which I recreated the dish. The milk-based sauce bathing the shrimp and peas is textbook-typical of American patty shell fillings.

Similarly archetypal renditions did survive in some of Singapore’s Western restaurants up until the 1990s. For instance, patty shells filled with chicken and mushrooms in white wine sauce were offered at Novotel Orchid Inn Hotel’s Wienerwald restaurant in 1983, while in 1992, The Ship served shells cradling chicken à la King.18

A Vase Difference

However, as is often the case in food heritage, there is another side to the story. Khir Johari, food scholar and author of the award-winning book, The Food of Singapore Malays, schooled me about the Malay incarnation of pie tee – kuih jambang (flower vase kuih). According to him, Malay kuih jambang “filling was always daging [beef], which was reserved for special occasions, as people were mostly pescatarian then”. It was spiced with garlic, ginger, galangal and coriander seeds, and the filled shell decorated with “celery, carrot, pennywort, chives, spring onions and red chilli ‘flowers’, so it really looked like a vase. This is what I remember”.19

Showing me his family kuih jambang moulds, Khir cited Kampong Glam and Joo Chiat as two of Singapore’s established metalsmith hubs, where many cooks sought and bought tools and kitchenware for making kuih and cakes. His own smallest mould makes shells barely bigger than walnuts, which would be served to children with a chicken filling. Two larger and much heavier heart-shaped moulds are not in fact “hearts”: in Malay culture this shape is called sirih, after betel leaves. Another mould has a wajik (diamond) shape. “So much of Malay geometry is based on rhombuses… and wajik also tessellate into stars,” as evidenced in Islamic mosaic, textile and embroidery design, noted Khir, who is also a trained mathematician.20 Fascinatingly, his sirih and wajik moulds are twins of Fannie Farmer’s timbale irons.

Kuih jambang, a celebratory dish, was also a prized kuih hantaran (betrothal kuih) exchanged between the families of engaged couples. Khir recalled a story shared with him by the late local singer, Kartina Dahari. When she got married, her grandmother ordered two showpiece kuih for the wedding feast, one of which was kuih jambang. Making the filling was tasked solely to a cook locally esteemed for it, while on jambang duty were a few ladies known to be “expert at menghadap api, or facing the fire, and at frying perfect shells without breaking them”.21

Khir remembers a 78-year-old Malay doyenne telling him about her grandma making kuih jambang, implying that it has a multigenerational pedigree. While researching South African Cape Malay culture in Capetown, he found an old Dutch cookbook which talked about moulds for waffles, rosettes and cups, which is why he was inclined to say that the dish comes from the Low Countries.22

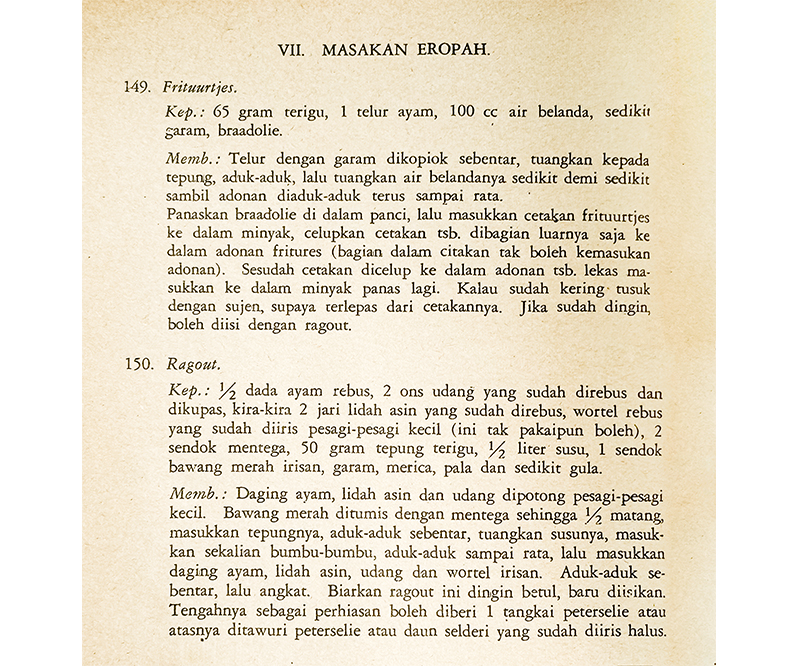

His conclusion is borne out by recipes in vintage cookery texts from Indonesia. In the iconic cookbook Pandai Masak 1 by hallowed Javanese cookery writer and restaurateur Julie Sutardjana, also known as “Nyonya Rumah”, there is a chapter titled “Masakan Eropah” (European Cooking).23 It contains Dutch-named recipes for “frituurtjes” (fritters) filled with “ragout” (stew) – pie tee shells holding chicken, prawn and beef tongue in a cream sauce. A similar ragout fills Susie Hing’s Java Kwei Patti.24

From illustrations in a later edition by Sutardjana and in Hing’s book, we can deduce that they both used the same type of mould – a fluted thin metal cup with a thin rod handle. Much lighter than American irons, this would have been easier and less expensive to manufacture and thus more accessible to Indonesian home cooks.

Another popular 1950s cookbook, Buku Masakan Thursina by domestic science teacher Siti Mukmin, presents equivalent recipes for “fritures” (fritters).25 Mukmin’s milk, egg and wheat flour “friture” batter formula is close to Sealtest’s, but her milk-free filling options are distinctly different – one features diced chicken and the other beef liver plus fatty beef, and both are bound with egg yolk-thickened broth. A third filling cloaks cooked diced vegetables with mayonnaise, a classic combination known as “Russian salad” in Europe.

Asian cooks also tweaked the fritter batter. To help the shells stay crispy in Southeast Asia’s humid weather, cooks would add rice flour, said Khir.26 As did other vintage formulas, a 1960s recipe in the Ipoh-published The Malayan Cookbook further adds “a pinch of chunam”, which in heritage architecture jargon often means “plaster” but here refers to slaked lime paste, or kapur sirih; its alkalinity gives the shells more colour and crunch.27 For this same reason, Sutardjana makes her batter with air belanda – “tonic water”.

Peranakan Perfusion

As the fillings of the two dishes are nigh identical, kueh pie tee may well be a riff on, or extension of, Peranakan-style popiah. Law Jia Jun, the young chef-founder of Province restaurant in Joo Chiat, remembers his Teochew Peranakan grandaunt making pie tee for special occasions like Chinese New Year. “She’d start by frying garlic, haybee [dried shrimp], shallots, and then she added taucheo [salted fermented soybeans] to fry and really intensify it before throwing in the bangkuang. If you don’t, she told me, ‘bu gou wei dao’ [it won’t be fragrant enough].” She garnished the pie tee with coriander leaves, prawns, a vinegar chilli sauce and sweet flour sauce. “It was super fun to eat,” Law fondly described.28

From the 1950s to the 1980s, pie tee appeared in many seminal local cookbooks featuring Peranakan recipes as well as Western-influenced local dishes. Among these are Ellice Handy’s My Favourite Recipes,29 Mrs Leong Yee Soo’s Singaporean Cooking,30 Yu Yoon Gee’s Nyonya Food, Satay and Padang Curry Cooking,31 Dorothy Ng’s Entertaining Cookbook32 and Terry Tan’s Her World Cookbook of Singapore Recipes.33 Their pie tee recipes all adhere to a classic filling template of bangkuang and bamboo shoots braised with garlic, taucheo, and a pork and seafood stock.

A 1978 restaurant review in the New Nation describes kueh pie tee as “a dish hardly ever found outside the home, and even then rarely… this is not an everyday Nonya dish”.34 Times do change, though. A decade later, when the New Paper asked local chefs to nominate candidates for a “national dish”, then vice-president of the Singapore Chefs’ Association Joe Yap chose Peranakan kueh pie tee.35 Today, one can find the dish at Peranakan restaurants and private-dining enterprises of every stripe – from quotidian to ultra-posh – and perhaps even topped with abalone, lobster or microgreens.

Top Shells

Croustade (pie crust) cups and rosettes have recently been enjoying a renaissance in fine dining in the West.36 Professional chef equipment makers in Europe are reviving old shapes and inventing new ones. While some call the cups croustades, a translation of the Swedish krustad into kitchen French, some dub them “pie tee” outright,37 a testament to the currently modish intermingling of Nordic and Asian culinary influences – and also to how the mould genre has boomeranged around the world and back.

New applications for them are being explored, such as the trend that Francisco Migoya, Head of Pastry at Copenhagen’s three-Michelin star Noma restaurant, started witnessing around 2019. “Chefs in the Western world have found an interesting use… instead of using the tool for frying doughs, they dip it in liquid nitrogen to get it very cold, and then they dip it in a liquid chocolate or even a sorbet base. The liquid freezes quickly, taking on the shape of the mould, and then is easy to release. It’s quite attractive, not to mention clever and delicious. So it works for cold and frozen preparations as well, which is fascinating to me,” he told me.38

Inspired by his grandaunt, Law Jia Jun puts his own stamp on pie tee by blending dehydrated kombu (kelp) powder and squid ink into his batter to boost its flavour. “The theme of Province’s summer menu this year is to showcase my own heritage… my generation of cooks, I feel, is trying to define what Singaporean cuisine can be, might be, or will be in the future,” he explained. After frying the jet-black shells, Law further dehydrates them for 12 hours to bestow upon them a denser, cracklier crunch.39

Their intense umami savour hums a deep oceanic bass note under the bamboo lobster meat, fried broccoli sprig, wild pepper leaf and lime gel that Law fills them with at point of service. Not his grandaunt’s kueh pie tee for sure, but one day, perhaps his grandchild’s.

To listen to his podcast discussing the origins of the dish, click here.

Christopher Tan is a food writer, author, educator and photographer. His most recent books are The Way of Kueh: Savouring & Saving Singapore’s Heritage Desserts (Epigram Books, 2019), a celebration of local kueh culture, and NerdBaker 2: Tales from the Yeast Indies (Epigram Books, 2024), about yeast cookery.

Christopher Tan is a food writer, author, educator and photographer. His most recent books are The Way of Kueh: Savouring & Saving Singapore’s Heritage Desserts (Epigram Books, 2019), a celebration of local kueh culture, and NerdBaker 2: Tales from the Yeast Indies (Epigram Books, 2024), about yeast cookery.Notes

-

Violet Oon, “Real Nonya-Style Fare – from a True Artist of the Wok…,” Straits Times, 27 January 1980, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Francis Wong, “Battle of the 28-Dish Makan,” Straits Times, 7 March 1954, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Susie Hing, In a Malayan Kitchen (Singapore: Mun Seong Press, 1956), 83. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 641.59595 HIN-[RFL]) ↩

-

Chan Sow Lin, Chinese Party Book, 2nd ed. (S.l.: s.n., 1960), 27. Chan fries the shells in orthodox fashion, but unusually calls for a wheat-free batter and a simple stir-fried filling. ↩

-

“Page 18 Advertisements Column 1: On the Second Day of Christmas, Have a Merry Cooking Spree!” Straits Times, 28 November 1980, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Marc McWilliams, ed., Food and Material Culture: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2013 (Great Britain: Prospect Books, 2014), 184; Bartolomeo Scappi, Opera Dell’arte Del Cucinare 1570 (Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 390. ↩

-

Scappi, Opera Dell’arte Del Cucinare 1570, 372. ↩

-

Priscilla Mary Işın, “Moulds for Shaping and Decorating Food in Turkey,” in Food and Material Culture: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2013, ed. Marc McWilliams (Great Britain: Prospect Books, 2014), 184, https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=yj8QDgAAQBAJ. In this essay, Işın also remarks on the moulds’ “remarkable resemblance” to livestock branding irons, unique to each family too. ↩

-

Mahmud Nedim bin Tosun, Aşçıbaşı – Bir Osmanlı Subayının Yemek Kitabı (Istanbul: Yapi Kredi Yayinlari, 1900), 163, https://www.yapikrediyayinlari.com.tr/yazarlar/mahmud-nedim-bin-tosun. ↩

-

“Krustadjärn,” Mölndals stadsmuseum, last updated 21 November 2017, https://digitaltmuseum.se/011024607964/krustadjarn. ↩

-

Fannie Merritt Farmer, The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook (United States: Little, Brown and Company, 1896), 314, Michigan State University, https://n2t.net/ark:/85335/m5fn15277. ↩

-

“The Gourmet Club…,” Singapore Free Press, 1 April 1958, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Poh Piah Skin Surprise,” New Nation, 19 January 1978, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Y.W.C.A.” Straits Times, 11 October 1913, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A.E. Llewellyn, ed., The Y.W.C.A. International Cookery Book of Malaya (Singapore: Malayan Committee of the Y.W.C.A., 1948), 178. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 641.59595 YWC). The pattie shell recipe appeared in the 1932 first edition and several editions thereafter. ↩

-

“Serve Fish Dishes for the Family Luncheons,” Morning Tribune, 6 January 1937, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sealtest Inc., Sealtest Kitchen Recipes: World’s Fair Edition (New York: Sealtest Inc., 1939), 37. ↩

-

“Roti John, Our Burger Version,” Straits Times, 10 April 1983, 10; “Page 19 Advertisements Column 1: Our U.S. Chicken Specials Are Really Something to Crow About,” Straits Times, 16 October 1992, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Khir Johari, interview, 14 May 2024. ↩

-

Khir Johari, interview, 14 May 2024. ↩

-

Khir Johari, interview, 14 May 2024. ↩

-

Khir Johari, interview, 14 May 2024. ↩

-

Nyonya Rumah (Julie Sutardjana), Pandai Masak Book 1, 16th ed. (Djakarta: P.T. Kinta, 1975), 66. The most famous of Sutardjana’s many books, Pandai Masak volumes 1 and 2 are compilations of over a decade’s worth of recipes from her newspaper cookery columns. ↩

-

Susie Hing, In a Malayan Kitchen, 83. Hing’s Kwei Patti filling is quite similar to what Hainanese-style chicken pies are stuffed with in Singapore and Malaysia, but this speaks to the ubiquity of white-sauced meat and vegetable collations in American and British cookery rather than to any kinship linked to the syllable “pie”. ↩

-

Siti Mukmin and Dahniar Jatim, Buku Masakan Thursina, 22nd ed. (Jakarta: Esbe Publishers, 1982), 116–18. ↩

-

Khir Johari, interview, 14 May 2024. ↩

-

Perak Catholic Centre, The Malayan Cookbook, 88. The book is undated but was published before 1964. ↩

-

Law Jia Jun, interview, 18 July 2024. ↩

-

Ellice Handy, My Favourite Recipes (Singapore: Malaya Publishing House, 1952). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.595 HAN-[JK]) ↩

-

Leong Yee Soo, Singaporean Cooking, vol. 2. (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1981). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.595957 LEO) ↩

-

Yu Yoon Gee, Nyonya Food, Satay and Padang Curry Cooking (Singapore: Tiger Press, 1976). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 641.8653 YU) ↩

-

Dorothy Ng, Dorothy Ng’s Entertaining Cookbook (Singapore: MPH Distributors, 1979). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING q641.595957 NG) ↩

-

Terry Tan, Her World Cookbook of Singapore Recipes (Singapore: Times Periodicals, 1982). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.595957 TAN) ↩

-

“As Good as Home Cooked Nonya Food,” New Nation, 17 February 1978, 10–11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lawrence Low and Loh Tuan Lee, “What’s Our National Dish?” New Paper, 8 August 1988, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Cúán Greene, “I Dropped the Croustade, Omos Digest #87, 19 March 2023, https://omos.substack.com/p/omos-digest-coustade-pastry. ↩

-

“Bunuelos/Pie Tee Moulds,” MoldBrothers, last accessed 29 September 2024, https://shop.moldbrothers.com/product-category/bunuelos-pie-tee/. ↩

-

Francisco Migoya, correspondence, 20 August 2024. ↩

-

This trick of drying the fried shells in fact appears in a 1581 German cookbook, as described by Priscilla Mary Işın in her essay, “Moulds for Shaping and Decorating Food in Turkey”. The recipe directs cooks to hold the fritters in front of a fire. ↩