Uncovering the Origins of Badang the Strongman

Relics of Badang the Strongman can be found throughout the region. But who was this enigmatic figure?

By William L. Gibson

On a lonely hill in a rubber plantation on the tiny island of Pulau Buru in the Riau Archipelago, there is a shrine above a grave said to be that of Badang the Strongman, whose exploits are recorded in the Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings), popularly known as the Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals. This is an important literary work composed around the 17th century by Tun Seri Lanang, the bendahara (prime minister) of the royal court of Johor, on the history and genealogy of the Malay kings of the Melaka Sultanate (1400–1511).1

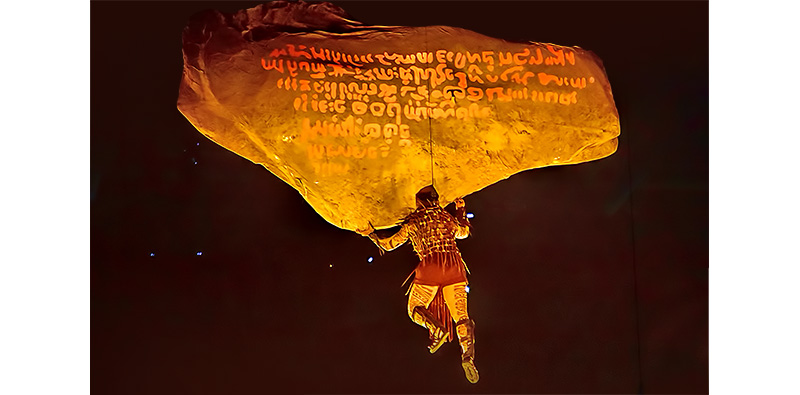

The legendary story of Badang throwing an enigmatic engraved rock from the top of present-day Fort Canning Hill to the southeastern side of the mouth of the Singapore River has become part of the mythology of modern Singapore.2

However, the Malay Annals does not mention any inscriptions on the rock that Badang hurled, and colonial accounts confused this stone with Badang’s gravestone, which some 19th-century accounts place in Johor. Where did the story of Badang come from? What does it have to do with the Singapore Stone? And where was the strongman buried?

A Herculean Feat

Badang’s story varies across different versions of the Sejarah Melayu (more than 30 manuscripts are known, some fragmentary), although certain details are consistent.3 He was an Orang Benua (an aboriginal people) and a slave of a man of Sayong, a 15th-century settlement on an upper tributary of the Johor River. The story goes that Badang had set fish traps in the Besisek River, but the next day all he found were bones and scales (hence the name “the river of scales”; known today as Sungai Sisek).

Eventually, Badang caught a hantu (a spirit or demon) stealing his fish. In exchange for not killing the spirit, Badang was granted supernatural strength by swallowing the spirit’s vomit. Eventually, Badang’s strength became known to Sri Rana Wikrama, the third raja (king) of the Kingdom of Singapura, who made him a military officer or Hulubalang (the military nobility of the classical Malay kingdoms in Southeast Asia).

In a feat of strength, Badang tossed a massive stone from the king’s palace, atop what is today’s Fort Canning Hill, all the way to the mouth of the Singapore River, roughly 850 m away. Known variously as Tanjong Singhapura and Rocky Point, the accomplished Malay scholar and teacher Abdullah Abdul Kadir (better known as Munsyi Abdullah) described in his autobiography, Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), the location as having “many large rocks, with little rivulets running between the fissures, moving like a snake that has been struck”. He reported that one of these stones, which resembled a garfish, was worshipped by the Orang Laut, or sea people: “To this rock they all made offerings in their fear of it, placing bunting on it treating it with reverence. ‘If we do not pay our respects to it,’ they said, ‘when we go in and out of the shallows it will send us to destruction’.”4

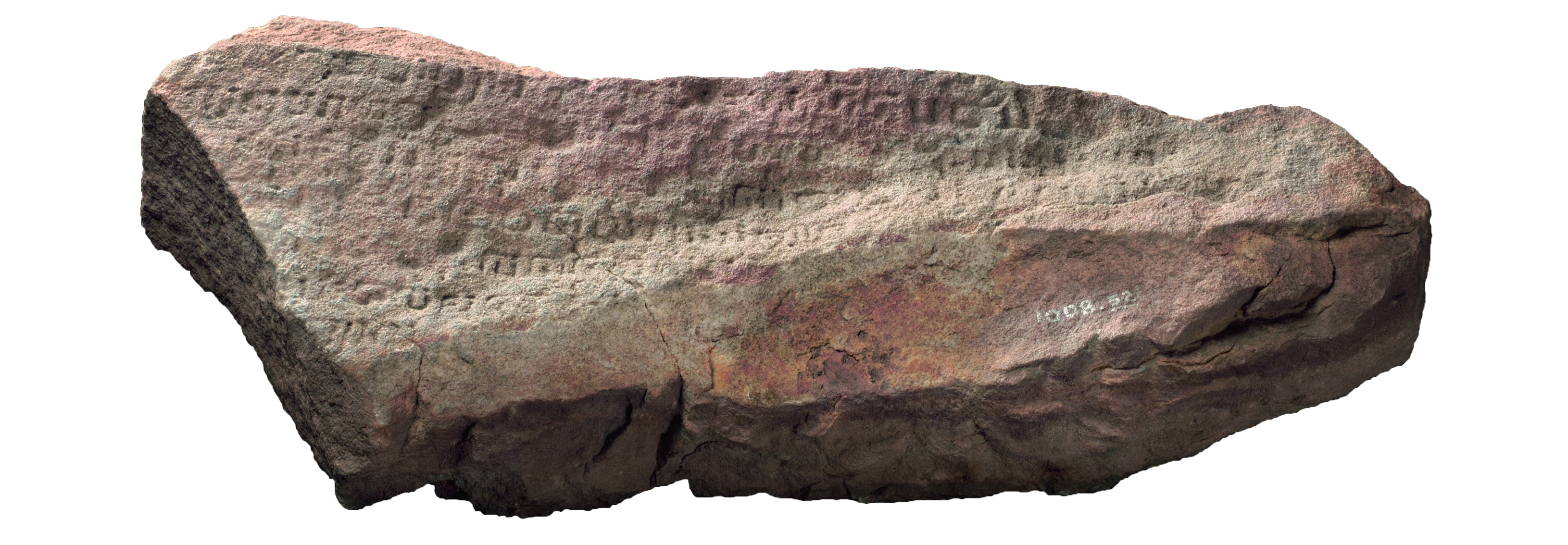

The Singapore Stone

The slab of rock with the illegible text was discovered in 1819. The rock was blown up in 1843 to enlarge the mouth of the Singapore River for the construction of Fort Canning and a fragment of it (estimated to be about 3 m tall, 2.7 m wide and 60–150 cm thick), known as the Singapore Stone today, is currently on display at the National Museum of Singapore.5

However, in the Sejarah Melayu, there is no mention of writing on the rock either before or after Badang had hurled it. The Annals merely note that Badang’s rock is located at the mouth of the river – but this may have been the garfish stone that Munsyi Abdullah had described in his autobiography. Nonetheless, the Singapore Stone and the story of Badang have been intertwined in the popular imagination of Singapore for almost as long as the colony itself.

In his 1834 book, The Malayan Peninsula, Peter James Begbie wrote that the three rocks associated with Badang – the one he hurled, the Singapore Stone and an engraved marker on his grave – were all one and the same. (Begbie was a captain with the East India Company’s Madras Artillery and was serving in Melaka when the book was published.) According to Begbie, the mysterious writing inscribed on the stone is a record of the story of Badang after his death. Yet, Begbie described the legend as “fabulous and childish”, indicating that it likely was something he had been told.6 But we have no idea who told Begbie this story. Was it one of the British colonists who had read the Annals? Could the connection between Badang and the Singapore Stone be a colonial invention?

The Annals also noted that when Badang died and was buried, the king of Kalinga (present-day northern Telangana, northeastern Andhra Pradesh, most of Odisha and a portion of Madhya Pradesh states) sent a monument to be erected over Badang’s grave. In the Scottish poet and Orientalist John Leyden’s English translation of the Sejarah Melayu – published posthumously in 1821 – he said that Badang was buried at “the point of the Streights [sic] of Singhapura”. The Kalinga monument was described as “two stone pillars” resembling an Islamic grave, which were visible “at the point of the bay”.7

The Raffles MS No. 18 or Raffles Manuscript 18 version dated 1612 (named thus because it once belonged to Stamford Raffles and is believed to be one of the earliest recensions of the original text) of the Annals described the monument as a single stone.8 Yet both Leyden’s and Raffles’ versions mention that this monument could be seen, hence the confusion with the engraved stone at the entrance to the river. So where was Badang buried?

Badang’s Grave

Most versions of the Annals mention that Badang is buried in a place called Buru (بورو). Today, on Pulau Buru, a small island south of Pulau Karimun in the Riau Archipelago, there is a shrine above a makam, or grave, believed to belong to Badang. Located on a remote hill in an old rubber plantation, the grave was likely the location of a nature shrine before the associations with Badang were made.

There are three large trees inside the enclosure. The middle tree, marked as sacred with a yellow cloth, is most likely a gaharu, or agarwood tree (Aquilaria malaccensis), whose fragrant wood has long been prized for making incense, prayer beads, and Hindu and Buddhist idols. When I visited the place in 2023, the locals told me that the Badang grave had been there since the 1960s. The oldest reference in print that I could locate dates to 1972.9

It is a long grave, measuring 3.25 m, with natural, uncarved stones for the batu nisan (gravestone). An engraved plaque dedicated in 2006, with a poem titled “Hikayat Datok Sibadang”, is embedded in the wall of the concrete structure above the grave. A sign reminds visitors that the grave is an officially protected monument that cannot be disturbed. The site has been managed by the Tanjung Balai Karimun Tourism Office since 2010.10

However, the exact location of Buru in the Annals is a mystery. There are a number of possible places around the region that could be the location of Buru. Nineteenth-century British commentators took it to mean Tanjong Buru, also known as Tanjong Bulus, located at the mouth of the Selat Tebrau, or the entrance to what period maps refer to as the “Old Straits of Singapore”, where Leyden said the monument could be found. This point is now known as Tanjong Piai in Johor, Malaysia. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European maps show the name of the tanjong (“cape” or “promontory” in Malay) as “Buro”, “Baro”, “Boro”, “Boulas” and “Bouro”. The spelling “Buru” did not appear until the 19th century, although “Boulus” and “Peie” (modern Piai) are found in mid-19th-century maps. Some European maps from this period used all three names.

Leyden named the tanjong “Barus”. Thomas Braddell (attorney-general of the Straits Settlements, 1867–82), in his 1851 annotated version of Leyden’s translation, wrote: “The champion was buried at Tanjong Buru, the extreme south west point of the Peninsula, opposite Point Macalister, or closer, Tanjong Gool in Singapore Island, but I cannot say if any traces remain of the monument erected by the Indian King.”11

In his 1828 travelogue, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China, John Crawfurd (second Resident of Singapore, 1823–26) referred to the tanjong as “Tanjung Bulus, (correctly, Buros,) the most southern extremity of the continent, of Asia”.12

The Methodist missionary William G. Shellabear – in his second Rumi (Romanised Malay) translation of the Sejarah Melayu (first edition in 1898) – called this tanjong “Bulus” but claimed that Badang was buried in Buru.13

R.O. Winstedt, the English Orientalist and colonial administrator, wrote in his 1932 paper on the history of Johor published in the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society that Badang was buried in “Tanjong Buru (alias Bulus) under a tombstone (nisan) sent by a raja of Kalinga”.14 However, as there is no record of an engraved stone being found on the tanjong, all these attributions were seemingly based merely on textual inference.

In some versions of the Annals, reference is made to Buru as a kingdom with a formidable navy of 40 warships, each capable of carrying hundreds of men. This Buru was given as a battle prize (di-anugerahi ia Buru) by the sultan of Melaka to a brave captain of his fleet following a battle at Pasai in Aceh, on the island of Sumatra, which could not have been a reference to tiny Pulau Buru nor is it a reference to the tanjong.15 Winstedt used “Tanjong Burus” in his 1938 Rumi translation of the Raffles MS No. 18 recension, noting that this version “incorrectly” used “Bruas” (برواس) for the name of a tanjong that was near but not part of Singapore, i.e. Buru/Bulus.16

Yet there exists a town called Bruas (also spelled “Beruas”) in Perak today. Bruas was an ancient settlement that may have been mentioned as far back as Ptolemaic sources (305–30 BCE) and may have later been a port in the Srivijaya empire (7th–13th century CE). Bruas appears in the Sejarah Melayu correctly as such and, significantly, there are 15th- or 16th-century gravestones, known as batu Aceh, located in Kampong Kota in Bruas along Sungai Beruas at a place where the palace of the kingdom once stood. The graves are still there, known today as Makam Raja Beruas, or grave of the Beruas king. Winstedt believed that these were the final resting places of Indian-Muslim missionaries from Gujarat, India.17

Tomé Pires, a 16th-century Portuguese diplomat and writer, noted in the early 1500s that Bruas traded with Pasai, and that men from Gujarat were also found at Pasai, suggesting another mode of transmission for both the stones and stories about strongmen.18

Could these gravestones at Bruas have been what inspired the story of the raja of Kalinga sending a monument for Badang’s grave at Buru? Or did this story come from further afield?

There are carved stone pillars inscribed in Tamil (one is dated 1088) found at Barus, on the west coast of north Sumatra, offering a different trajectory for the story. Bruas is phonemically close to both Barus (باروس) and Buru, suggesting that the Buru in the Annals presents a localisation of Hindu stories to a peninsular context (or perhaps a copyist error that was repeated in subsequent editions). The trade and royal conflicts between Aceh, on the northwest tip of Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula account for this cross-fertilisation of folktales.

Yet another possibility is the well-known Sanskrit inscription carved into the side of a granite promontory facing the sea along the stretch of coast known as Pasir Panjang on the northwest coast of Pulau Karimun Besar, an island in the Riau Archipelago only a few kilometres from both Pulau Buru and Tanjong Buru/Bulus/Piai. The inscription, believed to date to the late Srivijaya period, describes indentations running down the sloping cliff as Buddha’s footprints. But legend has it that these indentations are the footprints of Badang.19

Not far from the inscription is a freshwater spring that was “regarded as keramat (miracle-working) by local people, who would have come to take its water for ritual and medicinal purposes”.20 When I visited the site in 2023, the inscription had been converted into a shrine with Taoist and Hindu elements erected over the inscription.

Folk Hero

Badang’s Orang Benua origin is a significant part of his local identity. In 1847, J.R. Logan, founder and editor of the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, noted that the Malays called the Orang Benua living around Sayong both orang utan (“men of the forest”) and orang dalat liar (“wild men of the interior”). In the Annals, Badang’s power bestowed by the river spirit is linked to this Malay interpretation of Orang Benua as being similar to orangutans (great apes native to Borneo and Sumatra).21 However, the supernatural element of the tale was not limited to Johor.

In 1885, the British colonial administrator William Edward Maxwell recounted the story of Toh Kuala Bidor, a poor fisherman from Pasai, who relocates with his wife to the Bidor River in Perak. He catches a jinn stealing his fish – the spirit was dressed like a haji and wore a green turban, indicating he was an Islamic spirit – who suggests that Toh Kuala Bidor swallows his spit so that he can become “the greatest chief in Perak”. Indeed, he later became the laksamana (admiral) of Perak.22 The laksamana in 1885 claimed to be a seventh-generation descendant of this semi-mythical figure.

Maxwell recalled a similar account in a Perak folktale. An old woman by the name of Nenek Kemang encounters two sisters who, upon the death of their parents, are enslaved by their uncle over a debt of five dollars, owed by their parents. The woman asks their names and one of them said: “I am called Upik and my sister’s name is Dewi.” Then the old woman instructs Upik to open her mouth and when she does so, the old woman spits into it and then touches Dewi in the waist. She also gives the sisters a tuai (a special knife for harvesting paddy) and teaches them rice cultivation – the knowledge that has been passed down to the present day.23

These stories have clear resonances with the Badang tale in the Annals, but there are others from further afield than Perak.

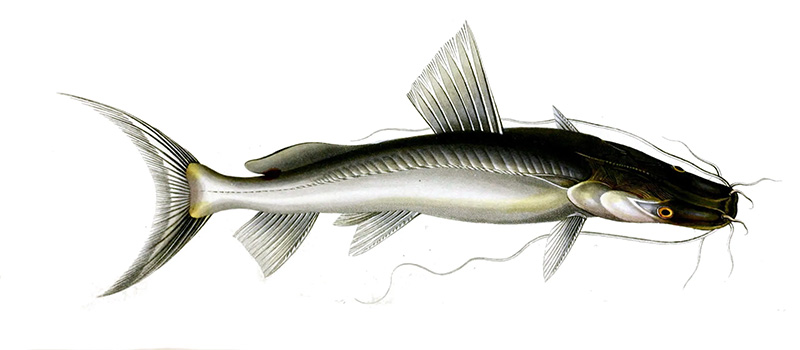

There is a version recorded in the Folktales of Assam (1916) by Jnanadabhiram Barooah (a variant spelling of Barua) – a notable Indian Assamese writer, dramatist and barrister – and told by the Barua (or Baru) people from Chittagong in Assam titled “The Tale of a Singara Fish”. The singara or singhara (Sperata seenghala) is a type of large catfish commonly found in India and frequently featured in Bengali folktales (and makes for a flavourful curry dish). In this version, a poor fisherman catches the king of the singara fish, who, while riding a cow belonging to the fisherman, encounters a monster. The fish-king manages to subdue the monster who, to ensure its release, vomits a ring that becomes a house of gold for the fisherman. In the end, the fish-king reveals himself to be a human in disguise and the two agree to live together in the gold mansion.24

The image of a king riding a cow, a vahana or animal mount, indicates the Hindu origins of the tale, which suggests that it may predate the Malay versions. The names Barua/Baru may also be indicators of the links to Barus/Buru in the Badang tale in the Annals. Another tale in the Barooah collection tells of a contest arranged by a king between a strong man and a trickster, which also carries elements of the Badang tale in which the champion fights another strong man sent by the sultan of Perlak, Aceh.25

It seems possible that versions of the story of Badang travelled between Pasai, Chittagong and Perak and then into the Sejarah Melayu, a long journey that continued when the site of Badang’s mystical grave was changed from Tanjong Buru in Johor to Pulau Buru in Riau, as toponyms shifted and the Annals became available to a wider audience in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Badang Venerated

The stone boulder that Badang hurled may have existed prior to the initial founding of the Kingdom of Singapura in 1299 and, if so, it was likely illegible to the people there.26

The Badang story presents an explanation of how the stone ended up at the mouth of the Singapore River and perhaps even what was written on it. There may have been a similar stone on the hill. Businessman William Henry Macleod Read, who first came to Singapore in 1841, recalled: “I remember a large block of the rock at the corner of Government House, where Fort Canning is now; but during the absence of the Governor at Penang on one occasion the convicts requiring stone to replace the road, chipped up the valuable relic of antiquity, and thus all trace of our past history was lost.”27 This would suggest that there were once two engraved stones, and explains the trajectory from the hill to the river mouth: they were separated when Badang tossed one of them.

Logan reported that for the Malay people, rocks that were “in any way remarkable for size, form or position”, were considered keramat – sacred objects associated with “some ancient worthy [person]”.28 These stones were markers upon the landscape of a living history, a connection to both ancestors and the ancestral soil.

Beyond the stone in Singapore, there were also other stones associated with Badang that are recorded in the Annals. According to Winstedt, the ruler of Singapura, Sri Rana Wikrama, sent Badang to Kuala Sayong (in Johor) to get a tree-fruit (ulam kuras) for the royal table. “The branch broke and Badang’s head struck a rock and split it, so that to this day there is a rock at Kuala Sayong called the Split Rock (Batu Belah) and not far below it Badang’s boat (pelang) and between Batu Sawar and Seluyut his punt-pole (galah).”29

In 1826, a voyager up the Johor River was told that a “a convex ripple” near a sharp bend at Tanjong Putus, near Kota Tinggi, was the “remains of the weir”, or small dam, made by Badang.30 Putus means to sever or break up – this tanjong breaks up the flow of the river – and the toponym appears in versions of the Badang story in variants of the Annals that are less well known than Leyden’s translation or the Raffles MS No. 18 recension.31

While the Batu Belah and other markers of Badang in Johor appear to be gone today, his grave remains a source of authenticity for people in the region. As Virginia Matheson (an internationally recognised authority on traditional Malay literature and historiography) pointed out the early 1980s, having the monument to such an illustrious hero on Pulau Buru created a sense of ancestral legitimacy for the ruling elite of Riau and a sense of empowerment for the residents of the islands.32 The Singapore Stone can be seen functioning in a similar fashion, as a totem of legitimacy, for the city-state of Singapore.

This is an edited version of “Legendary Figures”, a chapter from Keramat, Sacred Relics and Forbidden Idols in Singapore by William L. Gibson (Routledge, 2024). The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library (call no. RSING 363.69095957 GIB).

[Note: This article has been updated to reflect the correct location of present-day Kalinga.]

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher based in Southeast Asia since 2005. A former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow of the National Library Singapore, his most recent book is Keramat, Sacred Relics and Forbidden Idols in Singapore (2024), published by Routledge as part of their Contemporary Southeast Asia series. His book Alfred Raquez and the French Experience of the Far East, 1898–1906 (2021) was published by Routledge as part of its Studies in the Modern History of Asia series. Gibson’s articles have appeared in Signal to Noise, PopMatters.com, The Mekong Review, Archipel, History and Anthropology, the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient and BiblioAsia, among others.

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher based in Southeast Asia since 2005. A former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow of the National Library Singapore, his most recent book is Keramat, Sacred Relics and Forbidden Idols in Singapore (2024), published by Routledge as part of their Contemporary Southeast Asia series. His book Alfred Raquez and the French Experience of the Far East, 1898–1906 (2021) was published by Routledge as part of its Studies in the Modern History of Asia series. Gibson’s articles have appeared in Signal to Noise, PopMatters.com, The Mekong Review, Archipel, History and Anthropology, the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient and BiblioAsia, among others.NOTES

-

Nor-Afidah Abdul Rahman, “Legends of the Malay Kings,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 47–49. ↩

-

Recent research suggests that the inscription is in the Kawi script and is probably in Sanskrit rather than Old Javanese. See Kelvin C. Yap, Tony Jiao and Francesco Perono Cacciafoco, “The Singapore Stone: Documenting the Origins, Destruction, Journey and Legacy of an Undeciphered Stone Monolith,” Histories 3, no. 3 (2023): 271–87, https://doi.org/10.3390/histories3030019. ↩

-

For a discussion of the variants of the Sejarah Melayu, see R. Roolvink, “The Variant Versions of the Malay Annals,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 123, no. 3 (1967): 301–24. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Written in Jawi between 1840 and 1843 and published in 1849, the Hikayat Abdullah is considered the most renowned of Munsyi Abdullah’s works. A.H. Hill, trans. “The Hikayat Abdullah,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 28, no. 3 (171) (June 1955): 130. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Yap, Jiao and Cacciafoco, “The Singapore Stone,” 271–87. ↩

-

Peter James Begbie, The Malayan Peninsula: Embracing Its History, Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants, Politics, Natural History, Etc. from Its Earliest Records (Madras: Vepery Mission Press, 1834), 358. (From National Library Online). Yet another version that links Badang to the stone is found in John Cameron, Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India (London: Smith, Elder, 1865), 49–51. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

John Leyden, Malay Annals: Translated from the Malay Language by the Late Dr. John Leyden with an Introduction by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1821), 63. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

R.O. Winstedt, “The Malay Annals or Sejarah Melayu: The Earliest Recension from MS. No. 18 of the Raffles Collection, in the Library of the Royal Asiatic Society, London,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 16, no. 3 (132) (December 1938): 1–226. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Adil Buyong, Sejarah Singapura: Rujukan Khas Mengenai Peristiwa2 Sebelum Tahun 1824 (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1972), 37. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 BUY-[HIS]) ↩

-

Dewi Saptiani and Amesih Amesih, “Eksistensi Makam Badang Sebagai Wisata Religi di Pulau Buru, Tanjung Balai Karimun,” Historia: Jurnal Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah 2, no. 1 (2017): 25–39, https://www.journal.unrika.ac.id/index.php/journalhistoria/article/view/1572. In the version related here, Badang was said to be a native of Pulau Buru. ↩

-

Thomas Braddell, “Abstract of the Sijara Malayu or Malayan Annals with Notes,” The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 5 (1851): 249, n. 7. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

This is a record of John Crawfurd’s commercial and diplomatic mission to the courts of Siam (now Thailand) and Cochin China (present-day South Vietnam) from 1821–22. See John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China (London: Printed by S. and R. Bentley, 1828), 41. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Sejarah Melayu or The Malay Annals (Singapura: Malaya Publishing House, 1960), 34, 44. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 SEJ) ↩

-

R.O. Winstedt, “A History of Johore (1365–1895 A.D.),” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 10, no. 3 (115) (December 1932): 4. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

R.O. Winstedt, “The Malay Annals or Sejarah Melayu,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 16, no. 3 (132) (December 1938): 134. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Winstedt, “The Malay Annals or Sejarah Melayu,” 65. ↩

-

R.O. Winstedt, “The Early Muhammadan Missionaries,” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, no. 81 (March 1920): 5–6. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Tomé Pires, The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires: An Account of the East, From the Red Sea to Japan, Written in Malacca and India in 1512–1515 (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1944), 144. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.8 HAK) ↩

-

Ian Caldwell and Ann Appleby Hazlewood, “‘The Holy Footprints of the Venerable Gautama’: A New Translation of the Pasir Panjang Inscription,” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 150, no. 3 (1994): 457–80. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). The Badang footprint story dates at least to the early 1980s and is still told today. See Virginia Matheson, “Kisah pelayaran ke Riau: Journey to Riau, 1984,” Indonesia Circle 13, no. 36 (1985): 3–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/03062848508729602. Matheson was told of the existence of supposed Buddhist inscriptions on Pulau Buru, but our guides did not know of them in 2023. A story related to us by local guides is that in the 1990s, an “Indian” man from Malaysia read the “Hindu” inscription on the Badang tombstone then built a shelter over the keramat that was later replaced with the current concrete structure. A variation of this story is mentioned by Carole Faucher. In this version, the strong man is not the Badang of the Annals but a man who lived during the time of Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah of Johor (1818–32). See Carole Faucher, “Territory, Boundaries and Ethnic Consciousness Among the Malays of the Riau Archipelago” in Géopolitique et Mondialisation: La Relation Asie du Sud-Est – Europe, ed. P. Lagayette (Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 2003), 87–106. The batu nisan on site today are natural rocks without any carvings or inscriptions. ↩

-

Caldwell and Hazlewood, “‘The Holy Footprints of the Venerable Gautama’,” 477. ↩

-

James Richardson Logan, “The Binua of Johore,” The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 1 (1847): 246, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.107692/page/n285/mode/2up. ↩

-

W.E. Maxwell, Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society: Notes and Queries Nos. 1–2 Edited by the Honorary Secretary (No. 1 Issued with No. 14 of the Journal of the Society) (Singapore: Printed at the Govt. Print. Off., 1885), 47–48. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 ROY) ↩

-

W.E. Maxwell, “The History of Perak from Native Sources,” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society no. 14 (December 1884): 309. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Jnanadabhiram Barooah, Folktales of Assam, 2nd ed. (Howrah, 1954), 94–96. ↩

-

Barooah, Folktales of Assam, 94–96. ↩

-

Iain Sinclair, “Traces of the Cholas in Old Singapura,” in Sojourners to Settlers – Tamils in Southeast Asia and Singapore, vol. 1, ed. Arun Mahizhnan and Nalina Gopal (Singapore: Indian Heritage Centre and Institute of Policy Studies, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, 2019), 48–58. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8948110959 SOJ) ↩

-

Quoted in Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times Singapore, vol. 1. (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1902), 94. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Logan, “The Binua of Johore,” 279. ↩

-

Winstedt, “A History of Johore (1365–1895 A.D.),” 4. There is a Kuala Sayong in Perak as well, yet another connection between Badang and Perak. ↩

-

“Trip to the Johore River,” Singapore Chronicle, August 1826, reprinted in John Henry Moor, Notices of the Indian Archipelago and Adjacent Countries (Singapore: Printed in Singapore by the Mission Press of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1837), 264–68. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

A. Samad Ahmad, ed., Sulatatus Salatin = Sejarah Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1979), 49. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 SEJ) ↩

-

Virginia Matheson, “Strategies of Survival: The Malay Royal Line of Lingga-Riau,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 17, no. 1 (March 1986): 24, n. 38. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩