From Colonial Vision to Key Memory Institution: A Short History of the National Library

The National Library began life in 1837 with a modest collection of 392 publications belonging to the Singapore Free School.

By Lim Tin Seng

Somewhat remarkably, the idea of the National Library in Singapore can be traced back to 1819. Stamford Raffles, who signed a treaty with Malay rulers that year to establish a trading post on the island, envisioned a college that would educate the sons of the Malay elite as well as employees of the British East India Company. Included in the plan was a library to “collect the scattered literature and traditions of the country, with whatever may illustrate their laws and customs, and to publish and circulate in a correct form the most important of these, with such other works as may be calculated to raise the character of the institution and to be useful or instructive to the people”.1

Sowing the Seed of Knowledge: Raffles’ Vision

It would take another four years before Raffles convened a meeting on 1 April 1823 to establish the college that would become the Singapore Institution (today’s Raffles Institution). Robert Morrison, one of the institution’s founding trustees and notable missionary and educationist, reiterated the importance of incorporating a library in the school to facilitate learning and provide “care” for the books in Singapore and the region. He also emphasised that “every possible facility” should be provided to ensure that the library’s collection was accessible and “rendered useful to the settlement”.2

Unfortunately, the physical establishment of the library was delayed because the Singapore Institution was only established in December 1837 after the Singapore Free School, an elementary school founded in 1834, relocated from High Street into the intended premises of the Singapore Institution on Bras Basah Road, bringing with it a library.3 With this move, the Singapore Institution Library was created with a humble collection – just 392 elementary education primers – described as so small it “in all probability [could] be locked into one medium-sized cupboard”.4

The collection would soon grow and the library became popular among the users. Although the library was opened to the general public, borrowing privileges were only extended to the institution’s students, teachers, donors and subscribers. Soon, calls were made for the establishment of a proper public library to serve the community beyond the school’s operating hours. Several key residents, including Straits Settlements Governor William J. Butterworth, held a meeting on 13 August 1844 where they passed a resolution for the establishment of such a library. The Singapore Library officially began operations on 22 January 1845.5

The Singapore Library: Singapore’s First Public Library

Although intended to serve a wider community, the Singapore Library, which occupied the “airy and spacious” north wing of the Singapore Institution building, was not a publicly funded institution but a private enterprise funded by its shareholders and three classes of subscribers (Classes II to IV). There was a tiered fee structure ranging from $1 (Class IV) to $2.50 (Class II, Class III and shareholders), with shareholders needing to pay an additional $40 joining fee. The fee determined the borrowing privileges and was subject to the subscriber’s residency in Singapore.6

The Singapore Library acquired its titles through appointed book agents as well as second-hand purchases targeting “standard works of science, history, biography, voyages, travels, poetry, fiction, etc”.7 The library also encouraged the public to donate “works related to the East, and especially the Eastern Archipelago”. Among those who responded was the Periodical Reading Club, which transferred its holdings to the Singapore Library, as well as prominent residents of the day. Today, some of these titles can be found in the National Library’s Rare Materials Collection.8

The Singapore Library was initially well received. Described as an “agreeable place of resort… [and] recreation”, it moved to the Town Hall (today’s Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall) in 1862 to make it more accessible.9 By 1863, however, the library faced financial difficulties due to the low subscription rate. An irate patron wrote to the Straits Times to complain that the books in the library were “ill-kept, ill-assorted, entirely without any connection or fullness in any division of literature”.10

By 1875, the library was saddled with a debt of $500 due to years of “mismanagement, neglect and a lack of subscribers”. It was described by the Straits Times as being in a “moribund condition” with no new books added since 1873.11

The Raffles Library and Museum: The “Q” Collection

The issues faced by the Singapore Library coincided with the colonial government’s consideration of a new museum, an idea influenced by a May 1873 exhibition of colonial products at London’s South Kensington Exhibition Building (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). The Singapore Legislative Council advocated for a similar permanent exhibition on the island to showcase commercial products and artefacts relating to the ethnology, antiquities, natural history and geology of the region.12

At the time, there was already a small museum in the Singapore Library to collect artefacts that “illustrate the general history and archaeology of Singapore and the Eastern Archipelago”. The museum was created in 1849 after Governor Butterworth presented the library with two ancient gold coins on behalf of the Temenggong of Johor.13

After Andrew Clarke became the new governor in November 1873, he refined the museum proposal to include a public library. The Singapore Library and its collection of books were transferred to the newly formed library, which was administered as a single entity with the museum known as the Raffles Library and Museum.

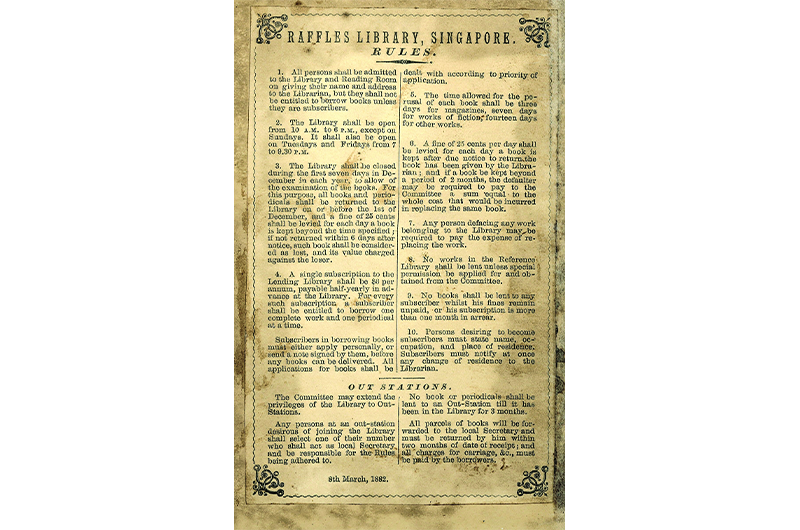

The library opened in the Town Hall on 14 September 1874, with the focus on collecting “valuable works relating to the Straits Settlements, and surrounding countries, as well as standard works on Botany, Zoology, Mineralogy, Geography, and the Arts and Sciences generally”. The library had three sections – a reference library, a reading room and a lending library – and operated on a two-tier subscription-based model. First-class subscribers paid an annual fee of $20, or $5 quarterly, for the privilege of borrowing two complete works and one periodical as well as exclusive access to new books for three months. Second-class subscribers paid $6 annually, or $1.50 quarterly, to borrow one complete work and one periodical.

To ensure that “every possible advantage may be placed within the reach of readers in the Settlement”, the library was also opened to non-subscribers but they were not permitted to borrow materials. James Collins, headmaster of the Singapore Institution, was appointed to oversee both the library and museum as librarian and curator.14

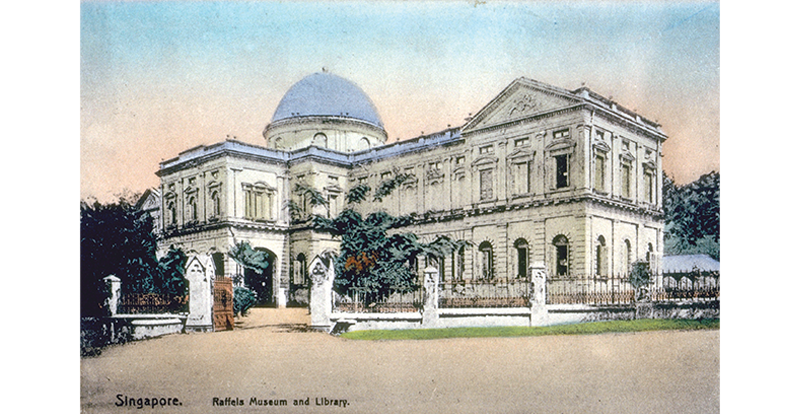

In 1877, the growing collections of the Raffles Library and Museum necessitated a move to the first and second floors of a new wing of the Singapore Institution, which had been renamed Raffles Institution. But this space soon proved inadequate, prompting the construction of a dedicated building on Stamford Road. This striking neoclassical structure, with its 90-foot (27 m) dome (now home to the National Museum of Singapore), opened on 12 October 1887. It housed the library on the ground floor and the museum on the first floor.15

The library’s initial collection consisted of 200 newly purchased books and the 3,000-volume collection from the Singapore Library. Through purchases and donations, the collection grew to over 26,000 volumes by the end of 1900.16

While some books were available for lending, others deemed “too valuable for circulation” were housed in the reference library. Some were even locked in “cases with glazed doors” accessible only “for reference on the application to the Librarian”. This collection, known as the “Q” Collection17 focused on “works related to Singapore, the Straits Settlements, and the Eastern Archipelago”.18 The “Q” collection also comprised items acquired through purchases and donations from institutions and individuals.19 (Today, it forms the core of the Rare Materials Collection of the National Library Singapore.)

By 1925, the “Q” collection had increased to about 900 volumes. Throughout the prewar years, it continued to expand with publications received under the Printers and Publishers Ordinance, materials from the library of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society and works from private libraries. Some prized titles obtained during this period include the 1849 lithographed edition of the Hikayat Abdullah, the autobiography of the Malay scholar and teacher Abdullah Abdul Kadir.20 By 1941, the “Q” collection had grown to 1,787 titles, forming a “reasonably complete” collection of works relating to the territories in British Malaya.21

In 1938, the library reported that it had nearly 3,600 subscribers and issued over 238,000 book loans, a significant increase from 200 subscribers and 5,000 book loans in 1874. To “induce the younger generation to take an interest in reading”, a Junior Library opened in 1923 for youths aged 10 to 21. By 1940, it had over 6,000 volumes.22

During the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), the Raffles Library and Museum was renamed Syonan Tosyokan and Syonan Hakubutsukan respectively. Due to the efforts of the Japanese museum directors and British staff, the collections of the museum and library remained largely intact. By the time the occupation ended, only about 8,000 books, mostly issued to subscribers before the fall of Singapore, were “unaccounted for”.23

The Raffles National Library: Becoming a National Library

The Raffles Library and Museum reopened to the public in December 1945 after the Japanese Occupation. By the end of 1946, subscriptions reached 3,850, with Asiatic members outnumbering European members for the first time. The library also began rebuilding its collection, reaching 70,000 volumes by the end of 1947.24

The 1950s saw significant improvements under trained librarians Louise E. Bridges and Leonard M. Harrod. Bridges, Librarian from 1951 to 1952, transformed the library with a limited budget of $4,000 from a “dim, dingy [place] with cold echoing cement floors” into a place of “wonders”. She introduced comfortable furniture, proper shelving for newspapers and implemented the Dewey Decimal Classification System, bringing order to the previously “chaotic mess”. Bridges also established a booking system for popular titles, proposed an after-hours book return bin and implemented a fine system for overdue books. The first part-time branch library in the suburbs opened in Upper Serangoon in 1953.25

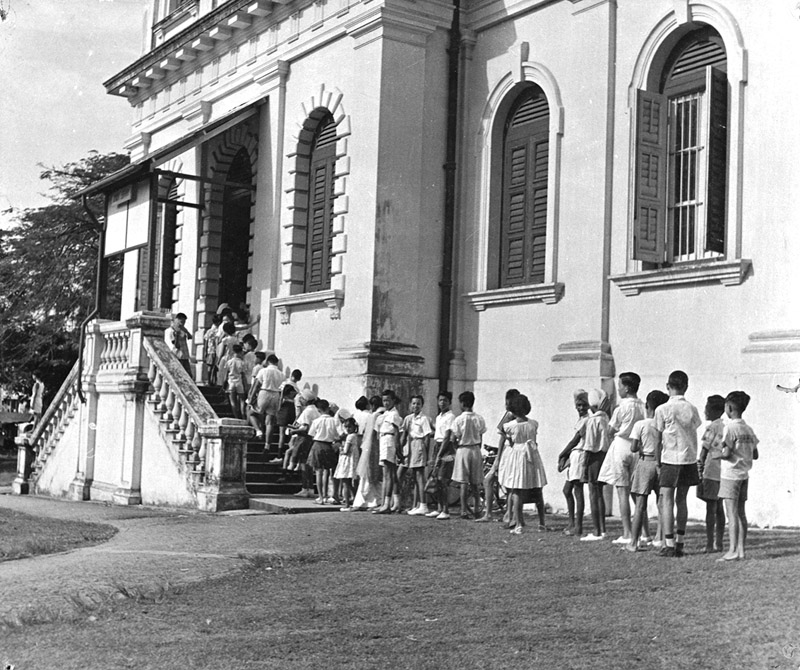

Children queuing to enter the Raffles Library, c. 1950s. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Children queuing to enter the Raffles Library, c. 1950s. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Harrod, who became Librarian in September 1954, expanded the collection to 80,000 volumes by 1955.26 He initiated an “Oriental” collection featuring books in Chinese, Malay and Tamil, and started a music section with about 4,500 pieces of sheet music, music albums and miniature scores by the end of 1958. Harrod also built more part-time branch libraries in the outlying areas and proposed a mobile library service.27

On 1 January 1955, Harrod was appointed Director of the Raffles Library after its administration was separated from that of the Raffles Museum. Plans were also made for the library to move into a new $2.5-million three-storey building on an adjacent site previously occupied by the St John’s Ambulance Headquarters and the British Council Hall.28

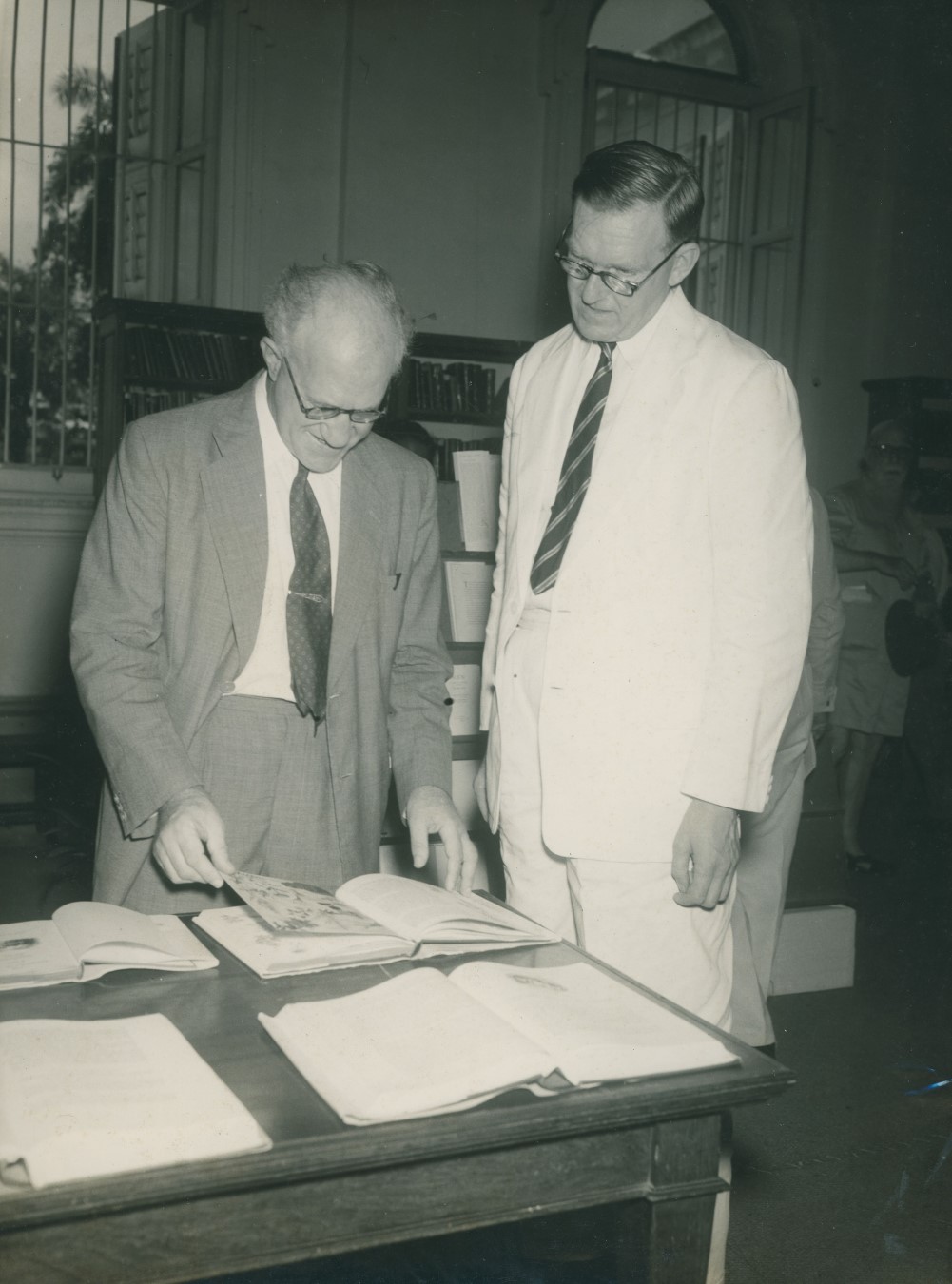

Leonard M. Harrod (right), director of the Raffles Library (1955–60), looks on as Attorney-General Edward John Davies is browsing a book. Collection of the National Library Singapore.

Leonard M. Harrod (right), director of the Raffles Library (1955–60), looks on as Attorney-General Edward John Davies is browsing a book. Collection of the National Library Singapore. The British Council building on Stamford Road, 1953. The building was part of St Andrew’ s School from 1875 to 1940. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The British Council building on Stamford Road, 1953. The building was part of St Andrew’ s School from 1875 to 1940. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The foundation stone of the new building was laid on 16 August 1957 by the businessman and philanthropist Lee Kong Chian, who had donated $375,000 on the condition that “the library should be made available to the public without charge and that books in the languages commonly spoken in Singapore and in European languages other than English be provided”.29

Lee Kong Chian laying the foundation stone for the new National Library building on Stamford Road, 1957. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Lee Kong Chian laying the foundation stone for the new National Library building on Stamford Road, 1957. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.A milestone was reached in 1958 when the Raffles National Library Ordinance came into effect, officially separating the library from the museum, and the Raffles Library was renamed Raffles National Library. It also became a free library where members no longer had to pay a subscription fee, although a $10 refundable deposit was still required.30

The National Library: Serving a New Nation

Harrod retired in January 1960 while the new National Library building on Stamford Road was still under construction. Hedwig Anuar, one of the few qualified local librarians, was seconded from the library of the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur to serve as the Raffles National Library’s interim director. She made history by becoming the first Malayan and first woman to head the library.31

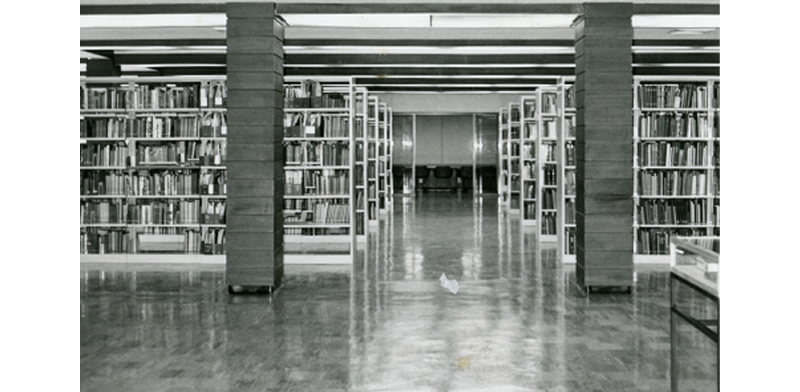

The new red-brick National Library building on Stamford Road was officially opened on 12 November 1960 by Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) Yusof Ishak. It accommodated a collection of some 140,000 volumes spread across an Adult Lending Library, a Children’s Library and a Reference Library. The building also included administrative offices, a conference room, lecture halls, as well as storage and maintenance spaces for library and archival materials.

On 9 December 1960, Raffles National Library was renamed the National Library after the Raffles National Library (Change of Name) Ordinance was passed.32

Anuar, who returned to the University of Malaya Library in 1961 when her stint as interim director ended, was appointed assistant director (supernumerary) of the National Library in 1962. She succeeded expatriate director Priscilla Taylor in 1965 after the latter completed her contract and left in 1964. Over the next two decades, Anuar made significant contributions to the growth and development of the National Library.33

In 1963, the National Library’s “Q” Collection made headlines when its bibliography, Books about Malaysia, was “hailed in all parts of the world” after it was published.34 Thereafter, the library received two major donations. The Penang-born merchant Tan Yeok Seong donated his 10,000-volume on Southeast Asian works to the library in 1964. This is now known as the Ya Yin Kwan Collection.

One year later, Mrs Loke Yew, mother of film magnate Loke Wan Tho (chairman of the board of the National Library from 1960 until his death in 1964) donated her son’s collection of 1,000 books and journals on Malayan flora, fauna, travel and arts, known today as the Gibson-Hill Collection.

These donations, along with the existing “Q” collection, formed the foundation of the South East Asia (SEA) Room which opened on 28 August 1964. Today, the SEA Collection has evolved into the National Library’s National Collection comprising the Rare Materials Collection, the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections and the Donors’ Collection.35

Anuar implemented various initiatives to encourage people to visit the library and to read.36 She launched the mobile library service, first proposed by Harrod, and set up fulltime branch libraries in housing estates to reach residents in the outlying areas. Queenstown Branch Library was the first to open in 1970. By 1990, there were eight branch libraries, contributing to a substantial increase in library membership from approximately 45,000 members in 1960 to over 640,000 members by 1990. Correspondingly, book borrowing surged from 703,000 loans to 9.2 million loans during the same period.37

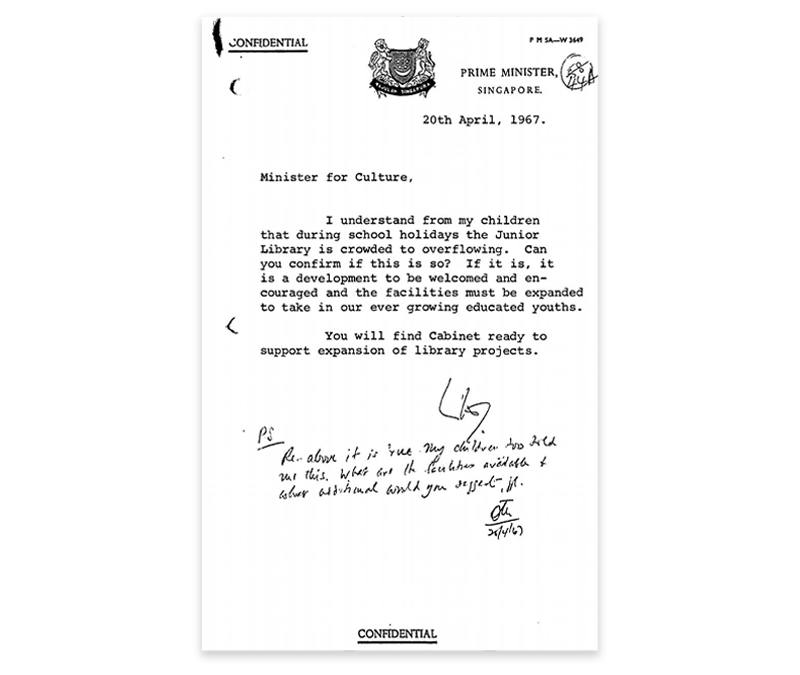

Anuar placed great emphasis on growing the children’s collection and sought to promote services to children. The Children’s Library became so popular that it was usually packed during the school holidays. On 20 April 1967, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew wrote to the Minister for Culture: “I understand from my children that during school holidays the Junior Library is crowded to overflowing. Can you confirm if this is so? If it is, it is a development to be welcomed and encouraged and the facilities must be expanded to take in our ever growing educated youths. You will find Cabinet ready to support expansion of library projects.”38

In the 1980s, Anuar led the National Library on its path to computerisation. Book borrowing, book returns and membership registration were computerised, and the Online Public Access Catalogue to search and locate library materials replaced card catalogues.39

The National Library Board: Revolutionising Library Services

In 1992, the Library 2000 Review Committee was convened to conduct a comprehensive review of library services in Singapore. A key outcome of the committee’s report, released in 1994, was the establishment of the National Library Board (NLB) on 1 September 1995 to oversee the development and management of the National Library and public libraries.40

With more autonomy and flexibility as a statutory board, NLB embarked on its journey of innovation and service excellence by leveraging new technology. In 1998, NLB became the first library system in the world to pioneer the use of radio frequency identification technology for all library processes and operations. Book borrowing and returning became faster and easier with automated self-check borrowing stations and automated bookdrops.41

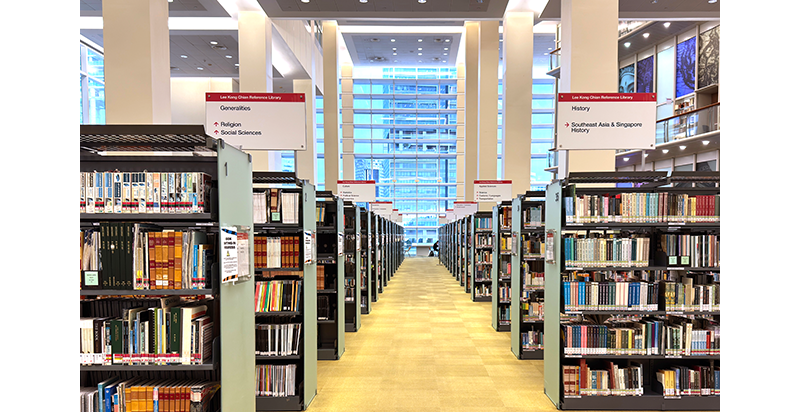

In tandem with technological advancements, the physical library network was enlarged significantly. New regional libraries in Tampines, Woodlands and Jurong provided expanded collections and services, while smaller branch libraries were strategically co-located with community centres or housed within shopping malls to encourage more visitors to the library. This expansion has resulted in a comprehensive network of 28 public libraries across the island today.42

One of the National Library’s main focus areas is the preservation and promotion of Singapore’s literary heritage for future generations. In 2003, it embarked on digitising materials relating to Singapore, including historical newspapers, rare and out-of-print books and digital content. These efforts led to the launch of Web Archive Singapore in 2006 (revamped in 2018) which offers access to archived Singapore websites, and NewspaperSG in 2010, an online resource of more than 200 Singapore and Malaya newspapers published since 1831.43

To grow the National Collection, the National Library welcomes donation of materials such as diaries, personal papers, letters, business documents, manuscripts, photographs and architectural plans. To date, it has received over 116,000 items from more than 425 individual donors, organisations and associations.44

In November 2012, the National Archives of Singapore – which is the “official custodian of all government records and the people’s collective memory” – became an institution of NLB. Two years later, on 1 January 2014, the Asian Film Archive, a nonprofit organisation established in 2005 to preserve Asian film heritage, became a subsidiary of NLB.45

Shaping the Future of Learning and Knowledge

Since its establishment, NLB has been guided by a number of blueprints over the last two decades. In 2005, the Library 2010: Libraries for Life, Knowledge for Success report was published with the focus on “expanding the role of libraries in the knowledge economy and to developing knowledge-enabled Singaporeans”. In 2011, NLB launched “Libraries for Life” which sought to “ensure that no one in society is left behind in this digital age and that libraries continue to be physical touch-points in the community”.46

These strategic plans have led to initiatives that benefit library users and improve NLB’s services and reach. Some examples include the nationwide reading initiative READ! Singapore in 2005, the Singapore Memory Project in 2012 (reconstituted as “Singapore Memories” in 2023) to collect “every individual’s memory and story… to contribute towards the Singapore Story”, the NLB Mobile app in 2014 (revamped in 2021) that provides access to the library’s digital services and collection, and the National Reading Movement in 2016 to promote reading within communities.47

NLB’s most recent strategic plan, LAB25, or “Libraries and Archives Blueprint 2025”, was launched in October 2021 to direct NLB’s five-year journey in its next phase of transformation. LAB25 aims to reimagine the libraries and archives of the future and to ensure that they remain vital and relevant in a rapidly evolving digital landscape.48

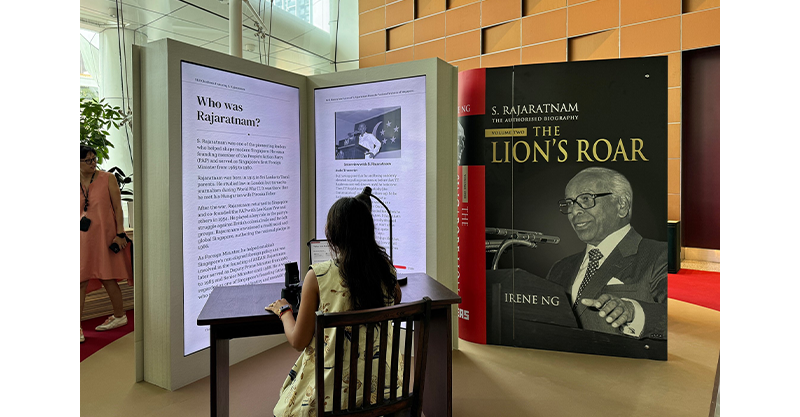

Aligned with this new blueprint, and with augmented reality and artificial intelligence (AI) being the buzzwords these days, NLB has embraced these emerging technologies to revolutionise user experience and improve operational efficiency. An example is the prototype of a generative AI-powered chatbook in 2024 featuring founding father S. Rajaratnam for users to learn about his life and contributions to Singapore, drawing from his authorised biography by former journalist and Member of Parliament Irene Ng as well as collections from the National Archives and National Library.49

Today, NLB is a key memory institution dedicated to preserving Singapore’s cultural heritage. As it looks to the future, it will continue to experiment and innovate to serve a new generation of library users. At the same time, NLB’s vision of nurturing readers for life, developing learning communities and creating a knowledgeable nation will remain at the heart of everything it does.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.Notes

-

Thomas Stamford Raffles, Minute by Sir T.S. Raffles on the Establishment of a Malay College at Singapore (n.p.: n.p., 1819), 17. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Thomas Stamford Raffles, Formation of the Singapore Institution, A.D. 1823 (Malacca: Mission Press, 1823), 57. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

After moving into the building on Bras Basah Road, the Singapore Free School was renamed Singapore Institution Free School. It was then renamed Singapore Institution in 1856. In the school’s annual report for 1868, the school was referred to as the Raffles Institution. See Jamie Koh and Vina Jie-Min Prasad, “Raffles Institution,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 25 November 2014; Singapore Institution Free School, Fourth Annual Report 1837–38 (Singapore: Singapore Free Press Office, 1838), 3–5, 59. (From National Library Online). ↩

-

Singapore Institution Free School, Fourth Annual Report 1837–38, 13; K.K. Seet, A Place for the People (Singapore: Times Books International, 1983), 8–13. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.55957 SEE) ↩

-

Singapore Institution Free School, Fourth Annual Report 1837–38, 59; Seet, A Place for the People, 16–18; “Singapore Library,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 15 August 1844, 2. (From NewspaperSG); Singapore Library, The First Report of the Singapore Library 1844 (Singapore: Singapore Library, 1845), 4. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Singapore Library, The First Report of the Singapore Library 1844, 4; Singapore Library, The Second Report of the Singapore Library 1846 (Singapore: Singapore Library, 1847), 7. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Singapore Library, The Fourth Report of the Singapore Library 1848 (Singapore: Singapore Library, 1849), 9–14. (From National Library Online); Seet, A Place for the People, 18; “Books Wanted,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 October 1844, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Singapore Library,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 10 October 1844, 5 (From NewspaperSG); Gracie Lee, “Collecting the Scattered Remains: The Raffles Library and Museum,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 2 (April–June 2016), 39–45; Ong Eng Chuan, “Rare Materials Collection,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 1 (January–April 2016), 2–5. ↩

-

Singapore Library, The Second Report of the Singapore Library 1846, 6–7; “It Will Be Seen by a Notice from the Secretary, That the Library…,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 18 September 1862, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Singapore Library,” Straits Times, 16 May 1863, 1; “The Singapore Library,” Straits Times, 30 May 1863, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Meeting of the Subscribers to the Singapore Library…,” Straits Times, 24 January 1874, 3; “Raffles Library & Museum,” Straits Times, 24 April 1875, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Yesterday’s Government Gazette Notifications…,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 17 May 1873, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore Library, The Fifth Report of the Singapore Library 1849 (Singapore: Singapore Library, 1850), 4, 10–12. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

“Government Notification 189: Raffles Library and Museum,” Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 12 September 1874, 477–78. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.51 SGG; microfilm no. NL5349); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1893 (Singapore: The Museum, 1894), 4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1875 (Singapore: The Museum, 1876), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1939 (Singapore: The Museum, 1940), 7. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874); “Raffles Library & Museum,” Straits Times, 24 April 1875, 1; “Raffles Institution Meeting,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 26 March 1874, 4. (From NewspaperSG); Seet, Place for the People, 23. ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1876 (Singapore: The Museum, 1877), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874)1; “Opening of the New Library and Museum,” Straits Times, 13 October 1887, 2 (From NewspaperSG); Gretchen Liu, One Hundred Years of the National Museum: Singapore 1887–1987 (Singapore: National Museum, 1987), 23. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 708.95957 LIU) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Catalogue of the Raffles Library, Singapore, 1900 (Singapore: American Mission Press, 1905), 1. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

The library’s collections were arranged alphabetically at the time, with the letter “Q” assigned to titles relating to Singapore, the Malayan peninsula and the Malay Archipelago in general. See Lee, “Collecting the Scattered Remains.” ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1888 (Singapore: The Museum, 1889), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1877 (Singapore: The Museum, 1878), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the year 1921 (Singapore: The Museum, 1922), 5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874) ↩

-

Lee, “Collecting the Scattered Remains”; Ong, “Rare Materials Collection.” ↩

-

Ang Seow Leng, “Stories of Abdullah,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 66–67. ↩

-

Padma Daniel “Descriptive Catalogue of the Books relating to Malaysia in the Raffles Museum & Library Singapore,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 19, no. 3 (December 1941): i. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Lee, “Collecting the Scattered Remains”; Ong, “Rare Materials Collection.” ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1940 (Singapore: The Museum, 1941), 8. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1923 (Singapore: The Museum, 1924), 9–10, 18. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874); “Supplementing Juvenile Education,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 February 1930, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Raffles Museum Treasures Safe,” Malaya Tribune, 23 October 1945, 2–3; “Donor Gives 60 Books to Raffles Library,” Sunday Tribune, 9 November 1947, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Raffles Museum Treasures Safe”; “Donor Gives 60 Books to Raffles Library”; “Asiatic Readers at Library Have Doubled,” Straits Times, 8 December 1946, 7; “More Asiatic Than European Readers,” Singapore Free Press, 24 April 1947, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Raffles Museum Singapore, Annual Report 1951 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1952), 13. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 069.095957 RAF); Nan Hall, “Louise of the Books,” Straits Times, 15 July 1951, 4; “New Look at Raffles Library,” Sunday Standard, 15 July 1951, 3; “Raffles Library May Set Up Suburban Branches,” Singapore Free Press, 15 June 1951. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Librarian for Singapore,” Indian Daily Mail, 6 August 1954, 1; “New Raffles Librarian Due Next Week,” Singapore Free Press, 4 September 1954, 5. (From NewspaperSG); “New Librarian for Singapore,” Indian Daily Mail, 6 August 1954, 1; “New Raffles Librarian Due Next Week,” Singapore Free Press, 4 September 1954, 5. (From NewspaperSG); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1963 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1964), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR-[AR]) ↩

-

Raffles Museum Singapore, Annual Report 1951, 1; “S’pore Is Not Library Minded,” Singapore Standard, 1 March 1955, 5; “Oriental Section for Raffles Library,” Straits Times, 1 March 1955, 4; “National Library Has 4,500 music pieces,” Singapore Standard, 10 September 1958, 6; “Taking Books to the Door,” Singapore Free Press, 24 January 1957, 5. (From NewspaperSG); Seet, A Place for the People, 103; Raffles Museum Singapore, Annual Report 1956 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1957), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 069.095957 RAF) ↩

-

“Start Made on Free Library,” Straits Times, 17 August 1957 4; “$2½ Mil. Library Is Free,” Singapore Free Press, 16 August 1957, 2; “City’s New $2 Mil Library,” Sunday Standard, 20 November 1955, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Start Made on Free Library,” Straits Times, 17 August 1957 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Raffles Museum Singapore, Annual Report 1955 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1956), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 069.095957 RAF); Raffles Museum Singapore, Annual Report 1957 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1958), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 069.095957 RAF); Seet, A Place for the People, 102; Hedwig Anuar, “Singapore’s National Library,” Straits Times Annual, 1 January 1962, 58–59. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“First Malayan to be Head of Raffles Library,” Straits Budget, 11 May 1960, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Out Goes the Name Raffles,” Straits Times, 21 November 1960, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Kristina Tom, “Makings of a Modern Classic,” Straits Times, 2 July 2005, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Books About Malaysia (Singapore: National Library, 1963–1967). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 016.9595 SIN) ↩

-

S. Rajaratnam, “The Opening of the South East Asia Room and Presentation of the Ya Yin Kwan Collection by Mr. Tan Yeok Seong at the National Library,” speech, National Library, 28 August 1964, transcript. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. PressR19640828); National Library Board Singapore, Annual Report 1960–63, 5; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1965 (Singapore: National Library, 1967), 5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1964 (Singapore: National Library, 1967), 1–2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); “National Collection,” National Library Board, accessed 28 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/visit-us/our-libraries-and-locations/libraries/national-library-singapore/collections/Collections/National-Collection; Lee, “Collecting the Scattered Remains”; Ong, “Rare Materials Collection.” ↩

-

Philip Lee, “First Lady of Books,” Straits Times, 1 November 2007, 62; Serena Toh, “Library Head All Set for New Career,” Straits Times, 1 October 1988, 21. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“400,000 Readers Is Library Target,” Straits Times, 23 January 1964, 4. (From NewspaperSG); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1964, 8; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1989/90 (Singapore: National Library, 1990), 3. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR) ↩

-

National Library Board, Singapore, Annual Report 1960–63 (Singapore: National Library Board, 1964). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); Ministry of Culture, “Library Division General Correspondence,” 1965–71. (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. AR 006), 309; Anuar, “Singapore’s National Library.” ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1979/80 (Singapore: National Library, 1980), 4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1980/81 (Singapore: National Library, 1981), 30. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1989/90, 3; Fauziah Ibrahim, SILAS at a Glance: The Singapore National Bibliographic Network (Singapore: National Library Board, 1996), 11–14. (From National Library Online); Rohaniah Saini, “On-Line System Boon to Library Users,” Straits Times, 20 May 1988, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Library 2000 Review Committee, Library 2000: Investing in a Learning Nation: Report of the Library 2000 Review Committee (Singapore: SNP Publishers, 1994), 5–14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q027.05957 SIN); “Library Board to Start Operations Next Month,” Straits Times, 19 August 1995, 31. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board Singapore, Annual Report 1998 (Singapore: National Library Board, 1999), 17–18. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.05957 SNLBAR) ↩

-

Hong Xinyi, The Remaking of Singapore’s Public Libraries (Singapore: National Library Board, 2019), 10–17. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Linus Lin, “17 Newspapers at a Click of the Mouse,” Straits Times, 29 January 2010. (From NewspaperSG); National Library Board, Annual Report 2004/2005 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2005), 21, accessed 27 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/about-us/press-room-and-publications/annual-reports. ↩

-

“Donate to Our Collections,” National Library Board, accessed 18 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/partner-us/Donate-to-our-Collections. ↩

-

Shashi Jayakumar, “Looking Back, Looking Forward,” BiblioAsia 15, no. 1 (April–June 2019): 2; Wendy Ang and Tan Huism, “Directors’ Note,” BiblioAsia 15, no. 1 (April–June 2019): 1; Abigail Huang, “Building History: From Stamford Road to Canning Rise,” BiblioAsia 15, no. 1 (April–June 2019): 10-13; Asian Film Archive, Annual Report 2022 (Singapore: Asian Film Archive), 1, accessed 27 March 2025, https://asianfilmarchive.org/report/. ↩

-

National Library Board, Annual Report 2004/2005 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2005), 19; Annual Report FY2010/FY2011 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2011), 11, 15, accessed 27 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/about-us/press-room-and-publications/annual-reports. ↩

-

“Reading Doesn’t Have to Be a Pain,” Straits Times, 25 May 2005, 2; “Use Your Smartphone to Borrow Library Books,” Straits Times, 24 September 2014, 6; “Seniors Can Learn Digital Skills at Libraries,” Straits Times, 27 February 2021, B2; “NLB Launches Two-month Festival to Promote Reading,” Today, 4 June 2016, 10; “Collection Points for Memories at 24 Libraries,” Straits Times, 6 September 2012, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“LAB25 (Libraries and Archives Blueprint 2025),” National Library Board, accessed 18 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/about-us/About-NLB/LAB-Libraries-and-Archives-Blueprint. ↩

-

“NLB’s 2024 Year in Preview – Innovative Services and New Experiences for All,” National Library Board, accessed 18 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/about-us/press-room-and-publications/media-releases/2023/2024-Year-in-Preview. ↩