Indian Migration into Malaya and Singapore During the British Period

Hailing from the Indian subcontinent – which comprises India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan and the Maldives – Indians have played an important role in the historical, economic, cultural and political development of Singapore.

Introduction

The Indian community in Singapore is heterogeneous, due to religious and linguistic differences. The term “Indian” refers to the people originating from the Indian subcontinent, which comprises India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan and the Maldives. As a community, Indians have played an important role in the historical, economic, cultural and political development of Singapore.

The arrival of Indians to Singapore reflects the long, historic association the Southeast Asian region has had with India. Before the 19th century, contact between India and Southeast Asia was characterised by a movement of goods and ideas. The nature of this contact somewhat changed with the British occupation of Malaya. Instead of merchants, traders and adventurers, more migrant labourers arrived at the region.

Early Contacts Between India and SouthEast Asia

Early contacts between India and Southeast Asia can be traced to the days of first millennium B.C. In Ramayana and Mahabharata, two of the greatest ancient Indian epics, the islands of the Malay Archipelago are referred to as Suvarna Dvipa and Yavana Dvipa (Krishnan, 1936, p. 1). Ancient Indian literary texts also make references to Southeast Asia, often describing it as Suvarnabhumi, or Land of Gold.

Archaeological and epigraphic evidences, such as Hindu/ Buddhist structures, Indian-styled objects and inscriptions in early Indian scripts, indicate the presence of Indian mercantile communities in several parts of early Southeast Asia. Indian traders tended to settle in areas, which were used as entrepots of trade, such as Kedah and Province Wellesley.

During this period of Hindu/Buddhist influence, which lasted till AD 1511, “Indianised” kingdoms flourished in Southeast Asia (Sandhu, 1969, p. 2). Moreover, Indian concepts of kingship and administrative institutions and ceremonies became deeply embedded in the socio-political institutions of some parts of Southeast Asia.

Indian literary influence in Southeast Asia is evident via the translations of Indian classical works into local literature. Wayang kulit, the popular shadow theatre in Indonesia, is based on the adventures of Rama, the divine hero of Ramayana. The Hikayat Pandawa, a Malay classic literature, is a translation of Mahabharata. Mythological stories from the Puranas and Panchatantra have also been adopted by Malay literature. Researchers have noted several instances of Sanskrit words being adopted and adapted in local languages.

At the early period, the Indians arriving at Malaya were mostly merchants, traders, missionaries and adventurers. With the increasing trade connections, the Indian merchants founded their own settlements. The Malacca Chetties, Chulias and Jawi Pekan are examples of Indian communities who settled in Malaya.

Most of the Indian merchant communities were self-contained entities, such as the “manikramam”, a South Indian mercantile corporation with its own regiment, temple and tank (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 4)

The Malacca Chetties were Hindu traders who had settled in Malacca; their name arose because they were primarily involved in commercial activities.

The Muslim traders in Malacca inter-married with the local women and became known as Jawi Pekan, thereby creating unique cultural traditions. The eminent Malay writer, Munshi Abdullah, was of mixed Arab, Tamil and Malay parentage and was proficient in Arabic, Tamil and Malay (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 7)

Indian Migration During British Period

It has been noted that 95 percent of Indians arriving into Malaya over the last 2,000 years seem to have entered the country between 1786 and 1957 (Sandhu, 1969, p. 13). Despite the long and historic association with Malaya, there were rarely large numbers of Indians in Malaya before the British period. Indians began to arrive into Malaya in 1786 when the British took control of Penang. However Indians were still not a significant part of the population till the latter half of the 19th century. According to Krishnan, modern Indian migration into Malaya began in 1833.

An increase in colonial agricultural activities in Malaya led to a demand for manpower, which could not be met by the local populace. The demand was satisfied by labour migrants from India, although such migration was seasonal.

With the abolition of slavery in the British territories in 1833, there was an even bigger demand for labour. This demand was precipitated by the “Industrial Revolution and the development of large-scale production in Britain” and the need to tap the British colonies for raw materials (Sandhu, 1969, p. 48). It was easier to recruit labour to the Straits Settlements as they were under the Indian Government till 1867 and so Indian laws applied to them. Majority of the Indian labourers migrated to Malaya and Singapore as assisted labourers, via the indentured labour system or the kangany system, while a few came as free labourers.

Indenture Labour System

The indenture labour system “provided the first complement of Indian labourer settlers to the Malay Peninsula” (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 12). Under this system, the Indian labourer was “indentured” to the employer for a period of five years and was paid fixed wages. Often, most of the labourers renewed their indenture at the end of five years. Indentured labour was recruited mainly through private companies based in South India and, secondly through speculators, who recruited on their own.

When the movement of labour to the Straits Settlements was legalised in 1872, the indenture period was reduced to three years. However, the indenture system was “riddled with abuses” as a result of poor living conditions, the questionable means of recruitment and the arduous ship journey, which caused high mortality and ill-health among the surviving passengers. Moreover the labourers were worked hard by the employers and their indebtedness was often extended, while their wages were lower than those who had come as free labourers (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 13–14).

With the rise of Indian nationalism, such a system was condemned as “near slavery”. The indenture system was finally abolished in 1910.

Kangany System

An alternative mode of recruiting labour for Malaya developed during the latter part of the 19th century. Known as the kangany system, it supplied most of the labour to the Malayan coffee and rubber plantations till 1938. Kangany is the Tamil word for overseer or superior. Unlike the indenture system whereby mostly males migrated, the kangany system paved the way for more families to migrate to Malaya.

Although it was seen as the most satisfactory solution for the growing demand for labour, the kangany system was criticised by Indian nationalists as exploitative as it “induced persons to migrate under false pretences” (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 19).

Poor economic conditions, including the Great Depression of 1930s, led to a decrease in demand for labour and thus a decline of the kangany recruitment. It was finally abolished in 1938 when all assisted emigration was banned by the Indian Government. Nevertheless, Indians continued to migrate to Malaya as free labourers.

Profile of Migrants From 1800s In Malaya

Before the large movement of labour into Malaya in the 1800s, Indian settlements in Malaya comprised mostly merchants and traders. From the 19th century, Indians worked as labourers in the plantations and in harbour ports. Prior to World War Two, labourers were the most numerous immigrants to Malaya.

The Indians arriving in Malaya as labourers were mainly from South India. Primarily because the Indian government had allowed recruitment for Malaya only from the Madras state, 90 percent of the labour migrants to Malaya were Tamil-speaking people. The rest of the migrants were Telegus and Malayalees from South India.

On the other hand, those recruited by the government were a mixture from Madras (still the majority), Punjab, Rajputana, Maharashtra and Bengal (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 15). From the 1820s, Indian labour was recruited directly by the Straits Settlements government for public and construction works, and municipal services. These were mainly English-educated South Indians and Ceylonese Tamils and Sikhs. The non-labour migrants tended to bring their families and relatives with them, thereby contributing to the Indian population growth.

Indians also came to Malaya as sepoys, lascars, domestic servants and camp followers when they accompanied the British who were stationed in the Straits Settlements. Another group that came to Malaya were the convicts during the early years of the 19th century. They were involved in various projects involving hard labour.

In the early years of the 20th century, Indians came in as lawyers, doctors, journalists, teachers and other university educated men.

The phenomenal growth of Singapore also attracted various North Indian businessmen, such as the Parsees, Sindhis, Marwaris and Gujeratis. By the early years of the 20th century, Singapore was the centre of growth for Indian commerce. These businessmen established themselves as wholesalers and retailers. South Indian Muslims (many of whom were mostly descendants of the historic traders), including Malabar Muslims also arrived in Singapore (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 35).

Among the Indian commercial groups were the Chettiars, a Tamil caste of businessmen and financiers who moved into the Straits Settlements by the middle of 19th century. One of the important subgroups was the Nattukottai Chettiars.

The migration of Indians as labourers declined after the war, while the migration of commercial and professional Indians predominated. Two acts were passed in 1953 that controlled the entry of Indians into Malaya, especially unskilled labour. Subsequently, only highly qualified professionals and technical personnel were allowed to enter the country. Unlike the labour migrants who were mainly Tamils, the latter type of migrants was more heterogeneous and hailed from different parts of India.

Arrival of Indians To Singapore

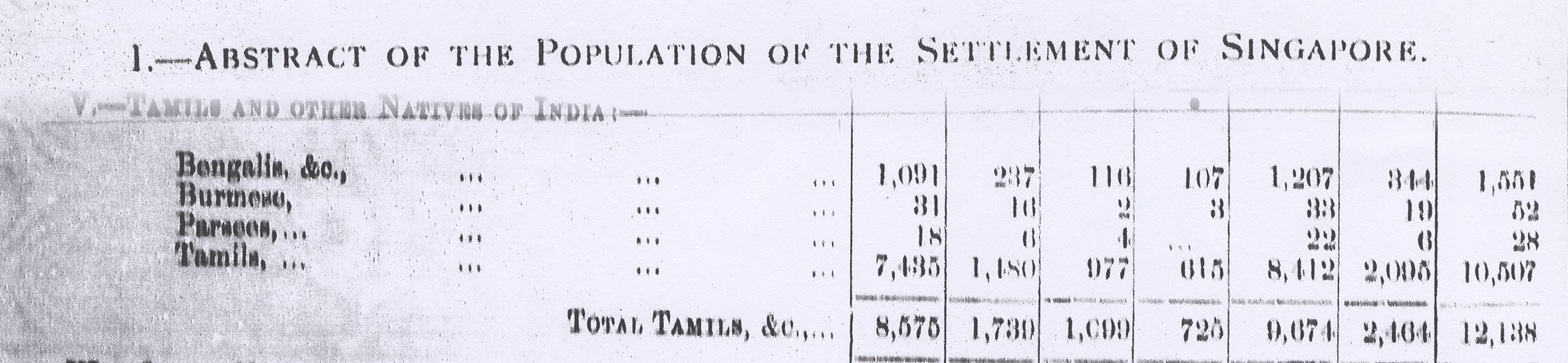

Indians were among the first migrants to arrive in Singapore. When Sir Stamford Raffles and William Farquhar landed in Singapore in 1819, they were accompanied by a trader from Penang, Narayana Pillay, and a troop of sepoys and a bazaar contingent. According to Sandhu, there is no record of Indians in Singapore when Raffles arrived (Sandhu, 1969, p. 178).

Subsequently, Indian labourers began to arrive in Singapore too, as per the migration pattern seen elsewhere in Malaya. They were employed in the sugar, pepper and gambier cultivations. Two years later, there were 132 Indians out of a total population of 4,727. This figure excludes the military garrison and camp-followers (Sandhu, 1969, p. 178).

When Singapore became a convict colony in 1825, Indian convicts in Bencoolen were transferred to Singapore. After 1860, Singapore was no longer used as a penal colony due to protests from the business community, but Indian convict labourers remained in Singapore till 1873 (Siddique, 1990, p. 9). While a few returned home, others married and settled down in Singapore, as shopkeepers, cow keepers/ milk-sellers, cart owners, or as public works employees.

Settlement Patterns of Indians in Singapore

Apart from the military garrisons, the majority of Indians in early Singapore had housed themselves in areas near to and around the city centre of the island. The initial settlement patterns of the Indians have been influenced by Raffles’ urban plan to allocate and create ethnic enclaves (A. Mani, 2006, p.791). Subsequently, Indians tended to settle in areas near to their places of employment.

According to Siddique, five main areas of Indian concentrations in Singapore can be distinguished from the 1800s - namely, the Chulia and Market street areas, High Street areas, the Naval Base in Sembawang, the railway/ port areas of Tanjong Pagar and the Serangoon Road area (Siddique, 1990, p. 7).

Prior to 1830s, the earliest concentration of Indians in Singapore (mainly Tamils) was in the Chulia and Market Street areas, which were situated at the western part of the commercial core, along Singapore River. “Most of these Indians were South Indian Chettiar and Tamil Muslim traders, financiers, money-changers, petty shopkeepers, and boatmen and other kinds of quayside workers” (Sandhu, 2006, p. 778; Siddique, 1990, p. 13). Indians also worked as doorkeepers and security men for commercial banks, offices and large stores in the commercial area, and carried out manual work in private residences within the European residential areas (A. Mani, 2006, p. 792).

When the British established a military base in Singapore after 1920, they built a naval base in Sembawang and an airbase in Changi. Many Indians were employed to work in these bases, and as a result, settled in the surrounding villages. The number of Indians who lived in Chong Pang, Jalan Kayu, Nee Soon and Yew Tee were higher than the Chinese and Malay populations (A. Mani, 2006, p. 793). Hence Sembawang became the third area of Indian concentration.

Another area of Indian concentration was the High Street area, which was occupied by Sindhi, Gujerati and Sikh cloth and electronics merchants. A few of the merchants also based themselves around Arab Street. Indians were also prominent in the areas around docks and railways at Tanjong Pagar. The latter group comprised mostly Tamils, Telegus and Malayalees.

Serangoon Road was first populated by Indians engaged in cattle-related activities. When cattle rearing in Serangoon Road was prohibited in 1936, the area became more densely populated by small businesses and their families. From the 1880s, predominantly Tamil South Indian businessmen began to settle here and on Farrer Road. Serangoon Road became a dominantly Indian area when government accommodation for labourers (mostly Tamils) was established along the area. As the Indian convicts jail was located at Bras Basah Road, Indian prison employees and those providing laundry services and food supplies to the prisoners also tended to settle near the prison; mostly along Selegie and Serangoon Roads, and the arterial networks (Siddique, 1990, p. 13; Sandhu, 2006, p. 778).

Besides the above areas of concentrations, Indians also settled near those areas set aside for plantations. The plantations hired mostly Indian labour, due to availability. As the plantations extended to Bukit Timah, Seletar, Pasir Panjang and Jurong, the Indian labourers tended to settle in these areas as well (Mani, 2006, p. 792).

From 1960s, there was a slight change in the settlement patterns of the Indians. Instead of the original areas of settlement, the “Housing and Development Board (HDB) estates became the new areas of settlement” (Mani, 2006, p. 793). With increasing affluence and education, younger Indians have moved out to newer towns, but nearer their original homes, such as Ang Mo Kio, Toa Payoh, Queenstown, MacPherson and Woodlands. Subsequently, Indians also settled in Yishun, Hougang, Tampines and Jurong.

As a result, the number of Indians staying in the previous areas of settlements has decreased. Even Serangoon Road, known as the Little India of Singapore, does not have a high concentration of Indian families. Despite this, Serangoon Road remains as the hub of Indian economic and cultural activities, mainly because of the concentration of Indian businesses in that area.

Builders of Early Singapore: Indians’ Contribution to Infrastructure and Economy

Indians have played an important role in the economic development of Singapore. They “have been conspicuous as textile and piece-goods wholesalers and retailers, money-lenders, civil servants, and especially labourers.” The “wholesale Asian textile trade of post-war Singapore” was mostly “controlled by the Singapore-based Indian textile merchants, particularly the Sindhis and Sikhs” (Sandhu, 2006, p. 781).

A third of the estimated 400 registered money-lenders and pawnbrokers in Singapore in 1947 were Indians. In 1963, about 80 percent of the 104 registered money-lenders were Indians. “The most important money-lenders among the Indians have been the Chettiars, though the Sikhs have also carried on a substantial money-lending business. The Chettiars’ clientele included not only Indian traders, contractors, and the like in Singapore and Malaya, but also Chinese miners and businessmen, European proprietary planters and others, and Malay royalty and civil servants” (Sandhu, 2006, p. 781).

Most importantly, the significance of Indian plantation labour to the economic growth of Singapore and Malaya cannot be underestimated. By the later half of the 19th century, rubber became Malaya’s staple export due to increased demand from Europe; Indian labour was used to augment the demand.

As the population in Singapore increased, there was an increased demand for development works, all of which were completed through convict labour. Convict labour was heavily tapped for the construction of roads, railways, bridges and government/public buildings, and for clearing and drainage projects.

“Filling up of swampy grounds; reclaiming large plots of land as intakes from the sea and river marshes; laying out plots of land for building purposes … ; blasting of rocks, erection of sea and river walls, bridges, viaducts and tunnels; survey and construction of roads were all executed by convicts” (Krishnan, 1936, p. 16).

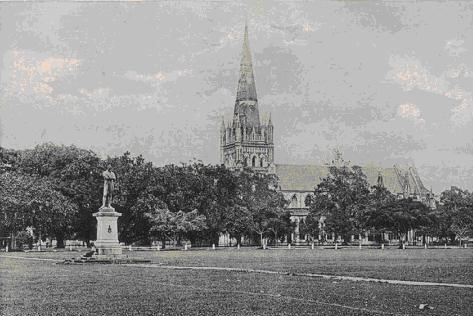

Indian convicts were responsible for building the St Andrew’s Cathedral, the Government House and the Sri Mariamman Temple in South Bridge Road. Their contribution to public works is tremendous, as they toiled to build the North and South Bridge Roads; Serangoon, Bedok and Thomson Roads; the road leading to Mount Faber and Bukit Timah; and most importantly the Causeway to Johore. They also widened the Bukit Timah canal to prepare the adjoining lands for cultivation and helped construct lighthouses as well as the signal station on Mount Faber.

The convicts also built their own prison building in Bras Basah Road, the Civil Jail in Pearl’s Hill, the court house, public offi ces, General Hospital and several other public buildings. Besides being involved in construction work, the convicts were also trained as draughtsmen, bricklayers, blacksmiths and carpenters. Indian convicts were also employed in government kilns, to maintain supply of bricks, tile lime and cement required for new building constructions.

Among the many prominent and successful Indians in early Singapore who have not only contributed to economic growth but to the social and cultural development of the Indian community, are Narayana Pillai and P. Govindasamy Pillai.

Narayana Pillai was one of the first Indians to arrive in Singapore in 1819, together with Raffles. He rose from chief clerk in the Treasury to become the first building contractor in Singapore. He started the first brick kiln in Tanjong Pagar and also managed a successful bazaar selling cotton goods. He was recognised as an Indian leader and given the authority to resolve disputes amongst them. He built the Sri Mariamman Temple in 1828, which is the oldest Hindu temple in Singapore.

Another successful Indian businessman was P. Govindasamy Pillai, better known as PGP, who established the popular PGP stores. At the height of his success, he owned several textile shops, flour and spice mills, a supermarket, and also invested in properties in the Serangoon area. He was known as a benevolent philanthropist who donated to the Perumal Temple, University of Malaya, amongst others, and helped to found the Indian Chamber of Commerce and the Ramakrishna Mission, to which he also donated generously.

Population Growth of Indians in Singapore

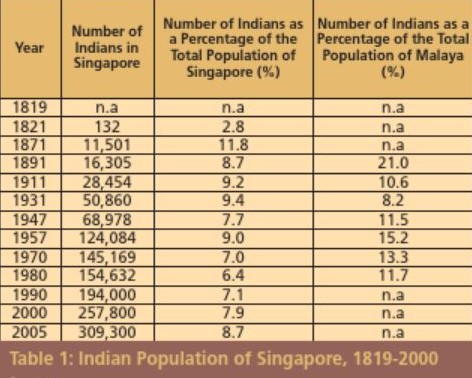

Today, the Indian community in Singapore constitutes about 8 percent of the total population. In 2005, the number of Indians in Singapore was about 309,300. However these figures did not include the non-resident workers who are estimated to be between 90,000 to 100,000 (Lal, 2006, p. 176).

Prior to the Second World War, the growth of the Indian population has been through labour migration; the “excess of immigrants over emigrants” (Sandhu, 1969, p. 185). The majority of Indian migrants in Malaya during the early stages were mostly males. There were about 171 women to every 1,000 men in Malaya in 1901. The number of Indian women increased as more came to work as labourers after labour migration was legalised and when more male labourers began to bring their families along. From 1930s, the improvement in the sex-ratio, as well as better health services contributed to the population growth via natural increase.

After the war, the increase in total Indian population was due to excess births as compared to deaths, and not through migration. During the 1947–57 period, significant increases in the number of Indians as compared to the total population was mostly evident in Singapore and Pahang (Sandhu, 1969, p. 197). This increase was estimated to be almost 80 percent (Sandhu, 1969, p. 190).

The number of Indians in Malaya declined in the middle of the 20th century as Indian migration was affected by the Great Depression of the 1930s and World War Two and the subsequent Japanese Occupation. Before the war, Indian labour in Malaya comprised 75 percent of total labour force. This figure declined to about 50 percent in 1947 (Arasaratnam, 1979, p. 38). The passing of two acts in 1953 to control Indian labour has steadily led to a decline in the proportion of Indian labourers to the total Indian population.

Trends in Occupational Diversity

A significant number of Indians were employed in the sugar, pepper and gambier, and later the rubber cultivations in Singapore. However, unlike the Malay Peninsula where majority of the Indians were plantation workers, Indians in Singapore were employed in various other occupations as well. Many Indians in Singapore were also engaged in small-time wholesale and retail trade.

When Raffles arrived in Singapore, his entourage included sepoys as well as a bazaar contingent of washermen (dhobis), tea-makers (chai-wallahs), milkmen and domestic servants (Lal, 2006, p. 176). These were a few of the traditional occupations that early Indians in Singapore were conspicuous in. The laundry business in early Singapore was monopolised by Indians. Majority of the dhoby lines were located around the Orchard Road area, today referred to as Dhoby Ghaut. Indians also monopolised the cattle and dairy farms.

Indians were also employed in the construction of roads and railways, in surveying lands and as clerks, dressers, plantation and office assistants, teachers, technicians, watchmen, caretakers and as technical personnel on the railways.

It was mostly the English-educated South Indians and Ceylonese Tamils who were employed in the railways, as clerks in government offices (including Public Works Department, Sanitation Department, telecommunication departments, etc) and in businesses, as well as teachers.

The North Indians, specifically Punjabi Sikhs, were employed as policemen, watchmen and caretakers (Siddique, 1990, p. 11). Besides the municipal services, Indians in Singapore were the key workers in the dockyards and military installations during the second half of the 19th century (Sandhu, 2006, p. 783) .

Over the recent decades, with “increasing sophistication, desire, and effort among the Indians to better themselves” and better educational opportunities, Indians have been moving away from “lowly paid wage-earning occupations into more profitable enterprises such as manufacturing, business and trade” (Sandhu, 2006, p. 782).

According to the population census of year 2000, the highest number of Indians (43.3 percent) was employed in professional, technical and managerial occupations. This is more than double that of 1990, where only about 22.3 percent of Indians were employed in such jobs (Leow, 2001, p. ix).

Ethnolinguistic and Religious Diversity

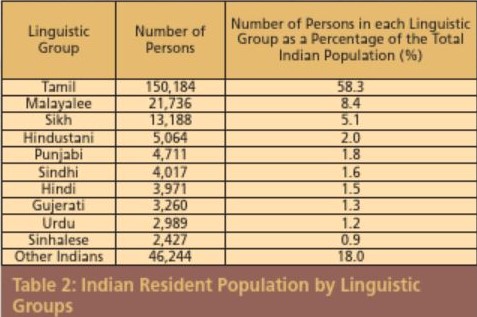

As a community, Indians are neither distinct nor homogeneous. They are “compartmentalised by occupational, religious, educational, and linguistic differences, and caste, as well as ethnic and sub-ethnic group differences based primarily on place of origin” (Siddique, 1990, p. 8). This compartmentalisation is sometimes viewed, in the broader sense, as North Indian vs. South Indian origin, and/or Hindu vs. Muslim religious practitioners.

The ethnic content of the Indian population in recent times has been conditioned by previous developments and patterns of labour migration. The majority of Indians in Singapore are generally Southern Hindus with the Tamils as the dominant group. According to Mani “three major linguistic groups became discernible” after the war, namely the Tamils, Malayalees and Punjabis (2006, p. 795).

There has been a substantial increase in North Indians after the first batch of Sikhs arrived as policemen in 1879 (Lal, 2006, p. 178). After the war, many more Indians arrived from North India, mostly as businessmen.

Conclusion

The Indian community in Singapore has come a long way from its days of being migrants. Though a minority, the Indian community is a vibrant and diverse group that has made significant contributions to the overall development of Singapore, and continues to do so. Indians from India continue to “migrate” to Singapore; such “migrants” are more heterogeneous, coming from various Indian states and range from unskilled labour to professionals.

Senior Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

A. Mani, “Indians in Singapore,” in Indian Communities in Southeast Asia, ed. K.S. Sandhu and A. Mani (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 788–809. (Call no. RSING 305.891411059 IND)

Brij V. Lal, Peter Reeves and Rajesh Rai, The Encyclopedia of the Indian Diaspora (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet in association with National University of Singapore, 2006). (Call no. RSING 909.0491411003 ENC)

Department of Statistics, Singapore, General Household Survey 2005. Socio-Demographic and Economic Characteristics (Singapore: Dept. of Statistics, 2006). (Call no. RSING 304.6095957 GEN)

Dhoraisingam S. Samuel, Singapore’s Heritage: Through Places of Historical Interest (Singapore: Elixir Consultancy Service, 1991), 207. (Call no. RSING 959.57 SAM-[HIS])

K. S. Sandhu, “Indian Immigration and Settlement in Singapore,” in Indian Communities in Southeast Asia, ed. K.S. Sandhu and A. Mani (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 774–87. (Call no. RSING 305.891411059 IND)

Kernial Singh Sandhu, Indians in Malaya: Some Aspects of Their Immigration and Settlement (1786–1957) (London: Cambridge U.P., 1969). (Call no. RSING 325.25409595 SAN)

Leow Bee Geok, Census of Population 2000: Demographic Characteristics. Statistical Release 1 (Singapore: Dept. of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2001). (Call no. RSING q304.6021095957 LEO)

Marjorie Doggett, Characters of Light (Singapore: Times Books International, 1985), 61. (Call no. RSING 722.4095957 DOG)

R. B. Krishnan, Indians in Malaya: A Pageant of Greater India: A Rapid Survey of Over 2,000 Years of Maritime and Colonising Activities Across the Bay of Bengal (Singapore: Malayan Publishers, 1936). (Call no. RRARE 325.25409595 KRI; microfilm NL8451)

Sharon Siddique and Nirmala Puru Shotam, Singapore’s Little India: Past, Present, and Future (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1990). (Call no. RSING 305.89141105957 SID)

Sinnappah Arasaratnam, Indians in Malaysia and Singapore (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1979). (Call no. RSING 325.25409595 ARA)

Tommy Koh et al., eds., Singapore: The Encyclopedia (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet in association with the National Heritage Board, 2006). (Call no. RSING 959.57003 SIN-[HIS])