Conceptualizing the Chinese World: Jinan University, Lee Kong Chian, and the Nanyang Connection

Using Jinan University as a case study, this essay looks at the under-explored area of education to study Chinese migration and the overseas Chinese communities. The university is the first institution established in China (founded in 1906 in Nanjing) dedicated to the education of Nanyang Chinese migrants and their offspring.

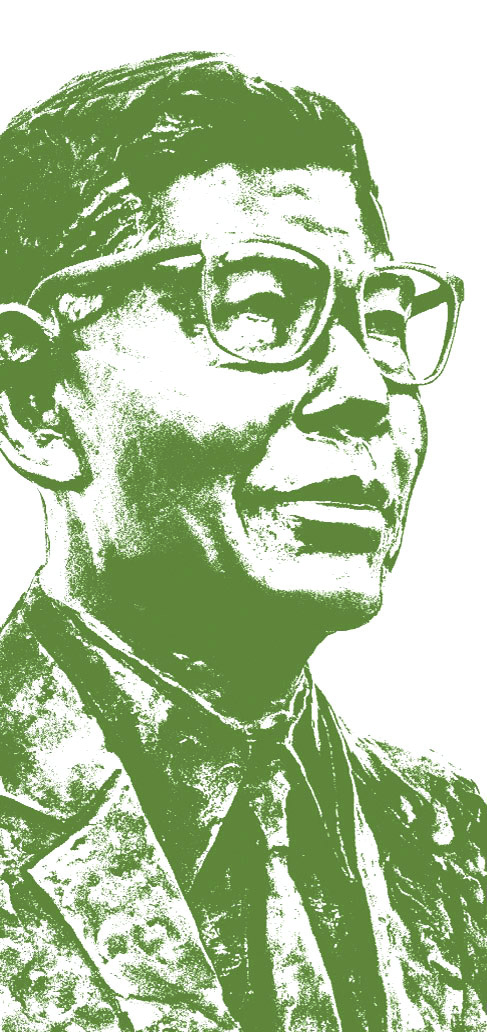

Lee Kong Chian

Lee Kong Chian

Historians of Modern China and Chinese migration have inadequately conceptualized the Chinese world. In particular, historically significant maritime activity has been confined to the periphery of studies on modern China, and scholars of Chinese migration have adopted the contradictory approach of using a China-centric “Chinese diaspora” theory to examine migrant communities in other countries. This paper uses the under-explored area of education to address such issues and provide a more satisfactory understanding of the Chinese world. I have based my case study on Jinan University (Jinan Daxue) because of its importance as the first school in China (founded during 1906 in Nanjing dedicated to the education of Nanyang (Southern Ocean or South Seas) Chinese migrants and their offspring.1 As the Nanyang (now Southeast Asia) was the main destination for Chinese migration, Jinan served as the cornerstone of governmental efforts to reach out to such migrants. These policies on migration have been largely neglected in the field of modern Chinese history. Furthermore, my selection of an educational institution rectifies the overemphasis on business activities in Chinese migration studies. Lee Kong Chian 李光前 (Li Guangqian), the famous rubber magnate, and his fellow students and intellectuals at Jinan feature prominently in my article because they traversed the two regions of China and the Nanyang in a trans-regional manner while being influenced by non-Chinese ideas and people. My trans-regional emphasis offers balance which has hitherto been absent from the historiographies of modern China and Chinese migration. Ultimately, my paper provides a new, holistic conceptualization of the Chinese world.

Trans-Regionalism And Education in the Chinese World

Few scholars of modern China have published analytical works on education.2 Studies on modern Chinese education have tended to contextualize educational developments against the limited backdrop of modernization during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The pre-occupation with the late Qing 清 period (c. 1839–1911) has meant that there have been few monographs on education in Republican China (1912–1949) with scopes beyond individual institutional histories.3 My research instead focuses on an educational case study which straddles both the late Qing and Republican eras. Furthermore, the fact that Jinan featured prominently in efforts by successive Chinese governments to reach out to migrants indicates that the study of education in modern Chinese history can be used to provide insight into state policies on migration and not just modernization.

At the same time, this paper addresses the inaccurate conceptualization of the Chinese world in the historiography on modern China. Historians have tended to examine continental events rather than the maritime sphere and migration. The post-1970s dominance of the approach favouring discussions of 18th century China has only exacerbated this imbalance. Such works have privileged internal developments instead of the previous emphasis on external influences exerted during the 19th century by Western powers.4 Established historians of maritime China and Chinese migration like Wang Gungwu have been content to remain on the historiographical periphery even as they have argued for the need to study maritime activity.5 Since the maritime arena was hardly inconsequential in modern Chinese history, we need to re-evaluate the status of the scholarship on the coastal regions and migration.

Despite the peripheral status of maritime China in the historiography on modern China, works on Chinese migration have tended to subscribe to a Sino-centric concept called “Chinese diaspora.” The diasporic framework implicitly places primacy on the point of departure or homeland, China, and this has led to social scientists like Ien Ang criticizing the notion of the “Chinese diaspora” for being imbalanced.6 Even so, historians have not addressed such criticism. Adam McKeown, for example, has posited the existence of “diasporic networks,” thereby overemphasizing the role of the mainland at the expense of migrants’ historical agency.7 Such continued emphasis on “diasporic networks” is inappropriate because these migrants were real people who had dreams, goals, and plans. Their actions were therefore neither controlled by the government in China nor entirely determined by developments on the mainland. Other conceptualizations also remain unsatisfactory. Wang Gungwu has advocated the use of the phrase, “Chinese overseas” (haiwai huaren), while expressing reservations about “diaspora,”8 but this contextualizes people of Chinese ethnicity as being “overseas” relative to the mainland. Wang’s conceptualization of Chinese migration has been appropriated by the Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas. The book scrupulously avoids any mention of “diaspora” yet portrays migration in terms of a concentric diagram with China constituting the core.9

Most of these works on Chinese migration have discussed business networks among migrant communities in destination countries. This emphasis has resulted in two problems. Firstly, there has been tension between the Sinocentric character of the popular “Chinese diaspora” theory and the localized nature of such case studies.10 Secondly, their focus on the economic dimension has indirectly perpetuated a form of Sino-centrism due to the preoccupation with the presence of seemingly quintessential Chinese cultural values within business practices.11 My research instead reflects a more balanced approach towards understanding the Chinese world by examining linkages between the mainland and Nanyang migrant communities without overemphasizing either connection. I have chosen to examine the history of a school in order to diverge from the conventional focus on Chinese business networks.

In contrast to the historical scholarship on modern China and Chinese migration, my paper calls for a holistic conceptualization of the Chinese world. I argue that a trans-regional framework is useful in this respect because it allows me to analyze the interaction between China and the Nanyang against the backdrop of Western and Japanese influences. My trans-regional perspective has been inspired by debates on trans-nationalism, which have explored the fluid movement of people and organizations across geopolitical boundaries in the more recent global age. However, the term “trans-regional,” rather than “trans-national,” is more suitable in this paper because my chronological focus is the period 1900–1942 and not the “global age.” Indeed, China was not a nation-state before 1911, and there were hardly any nations in the Nanyang before post-Second World War decolonization. Hence, both China and the Nanyang should instead be considered as “regions.”

The trans-regional approach is most evident from my emphasis on the lives of Jinan students and intellectuals, who moved freely between China and the Nanyang while interacting with non-Chinese people and influences. It is indeed tempting to make much of Jinan’s location in China and its existence during the pre-Second World War era, when links between the Nanyang Chinese and the mainland were at their strongest. Instead, I examine the experiences of researchers who worked at Jinan, where they founded the field of “Nanyang studies” 南洋研究 (Nanyang Yanjiu). These intellectuals subsequently migrated to the Nanyang, which became their new base of operations. I also analyze the profiles of several of the school’s students because they contributed greatly to the historical fabric of both China and the Nanyang despite their relatively small numbers.12

The Nanyang included the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, and Singapore.13 But in this article, I focus on personalities from the latter due to space constraints. Singapore is certainly a suitable choice to reflect the Nanyang connection in Jinan’s history and in the larger backdrop of the Chinese world. The island was historically part of the Singapore-Malaya (Xinma) entity that constituted the “heart of the Nanyang.”14 The statistics further support my choice: in his study of global Chinese migration over a century from 1840 to 1940, Adam McKeown has estimated that out of the 19–22 million Chinese who migrated to destinations around the world, almost one-third migrated to the Straits Settlements (of which Singapore was a part) and Malaya.15 This paper’s coverage ends in early 1942, when Singapore was conquered by the Japanese during the Pacific War.

My analysis of the Nanyang connection diverges from the official Jinan narrative, which has prioritized developments in China. This mainland-centric version of the school’s history has been unchallenged because there are no English monographs and articles on the school, and because Chinese works have been limited to official or semi-official accounts published by Jinan University Press. In focusing on the administration’s perspective, the official narrative has deprived the Nanyang students of their historical agency since their experiences have been marginalized even though they were real people with dreams, goals, and plans. The narrative also does not examine the activities of the Nanyang studies researchers after they moved to Singapore. It is no wonder that the official Jinan story has highlighted the origins of the school’s name, which can be traced back to the phrase “shuonanji” 朔南暨 (from north to south). This phrase was extracted from an ancient Chinese text, the Shujing (Book of Documents or Classic of Documents),16 thus falsely implying that Jinan was founded mainly to spread Chinese culture southward to the Nanyang.

Lee Kong Chian, Pioneer students, and the early years, 1900–1911

Jinan’s official narrative has accorded much credit for the school’s establishment to its founder, Duanfang 端方. He was a high-ranking Qing official who was one of the most prominent reformists in China during the final decades of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century.17 Nonetheless, Jinan’s founding needs to be contextualized against the backdrop of Western and Japanese-inspired reforms, which were implemented to address the vulnerability of imperial rule. The official narrative has also insufficiently examined the role of the Nanyang. The school was in fact established by the Qing court to harness the financial resources of the Nanyang Chinese and to cultivate political allegiance among younger generations of migrants in order to prop up its precarious rule.18 More tellingly, it was not Duanfang, but a low-ranking Qing official named Qian Xun, who actually initiated the Jinan project. Qian did so during a visit to the Nanyang in 1906 as part of a Qing Ministry of Education fact-finding mission.19 It is likely that he perceived the urgent need to seize the initiative and beat the competition by establishing Jinan in China, given the rising number of new schools in the Nanyang for Chinese migrants by the turn of the 20th century.20

Among the Jinan students who came from Singapore, Lee Kong Chian was an important figure. This man has been better known for his business acumen, his rags-to-riches story, and his philanthropy. He contributed immensely to the historical fabric of Singapore and the Nanyang. In 1916, he joined Tan Kah Kee’s (Chen Jiageng) rubber company, and 11 years later, at the age of 34, he started his own business. By 1942, Lee held leadership roles in organizations such as the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the Rubber Trade Association of Singapore, and the Overseas-Chinese Banking Corporation.21

Scholars have paid less attention to Lee’s activities before his entry into the business world. For example, he had an eclectic background, travelled between China and the Nanyang in his youth, and was the epitome of the successful Jinan student. Born on 18 October 1893 in Nan’an, Fujian Province 福建, Lee migrated from China to Singapore in 1903. On the island, he enrolled in the Anglo-Tamil (or Anglo-Indian) School, and attended Chinese classes at Yeung Ching (Yangzheng) School on weekends. During 1907, he enrolled in Tao Nan 道南 (Toh Lam or Dao Nan) School, where he won a scholarship in 1908 to study at Jinan Academy (Jinan Xuetang), the earliest incarnation of Jinan University.22 In early 1909, he arrived in Nanjing, where Jinan was based. He was part of the first group of students from Singapore to study at the Academy. These students had been selected by the General Chinese Trade Affairs Association in Singapore (Zhonghua Shanghui), the predecessor of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Jinan administrators had given responsibility for the selection of suitable students to the various academic societies and Chinese Chambers of Commerce in the Nanyang,23 and this reflected an acknowledgement of the importance of the Nanyang connection. At the school, Lee excelled academically. He was placed in the better of the two middle-school classes, and performed well in Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics. One of his Chinese essays was even used as a model essay. Lee graduated as the top student in his cohort in 1911.24

Upon graduating from middle school, Lee was one of only ten students from Jinan to be admitted to Qinghua High School (Qinghua Xuetang) in China. Yet he rejected the admission offer, having reached a consensus with the other nine that none of them would enrol at Qinghua. This was because Jinan administrators had previously promised to send successful students to Western countries for further studies. The promise was not honoured, possibly due to financial constraints since the Qing dynasty was on the verge of collapse. Lee therefore attended the Tangshan Railway and Mining College (Tangshan Lukuang Zhuan Xuetang), where he was taught by Englishmen and Scotsmen. At Tangshan, Lee joined the Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Alliance), the predecessor of the Kuomintang (Guomindang), since Tangshan was a hotbed of revolutionary sentiment. He arrived back in Singapore during 1912, after having left China due to the turmoil of the 1911 Revolution. Lee spent several years working, first at the Survey Department as a surveyor, and then as a translator for a Chinese newspaper and as a teacher at Tao Nan and Yeung Ching Schools. In 1915, he joined the business world and subsequently cemented his place in history.25

Lee was not, however, the only prominent Jinan student from Singapore who travelled between China and the Nanyang. Others among the first batch of students from the island included Lim Pang Gan 林邦彦 (Lin Bangyan) and Ho Pao Jen 何葆仁 (He Baoren or Ho Pao Jin). These two students were so close that they became sworn brothers at Jinan. They were both born in Fujian Province, Lim in Yongchun 永春 during 1894 and Ho in Xiamen during 1895. They arrived in Singapore during 1905. Both men enrolled at Tao Nan School in Singapore, and were subsequently selected to join Lee Kong Chian at Jinan. There was indeed a strong Tao Nan connection in the initial batch of Singapore students at Jinan: out of an intake of 38 from the island, 18 came from Tao Nan.26 At Jinan, Lim and Ho did not join Lee in the best middle-school class, but were instead placed in the second-ranked middle-school class. The sworn brothers’ paths split amidst the upheaval of the 1911 Revolution. Lim returned to Singapore, where he worked as a clerk by day and as a Chinese tuition teacher at night. He also worked as a bill collector, and in the tobacco business. Meanwhile, Ho pursued further studies at Fudan University (Fudan Daxue) in Shanghai 上海, representing Fudan in a patriotic movement of student organizations during the 1919 May Fourth Movement. Ho subsequently headed to the United States in 1920 to study commerce at the University of Washington. He then enrolled in the University of Illinois to pursue Masters and Ph.D. studies on Governance and Economics, after which he returned to Fudan in 1924 as a professor of Political Science.

Lim and Ho continued to keep in touch. It was Ho who recommended Lim for a book-keeping job at a provision shop. Both of them were prominent members of the Chinese community in Singapore. Lim held various appointments on the boards of organizations and schools, including those of Chung Hwa Girls’ School (which he assisted in establishing), Chung Cheng 中正 High School, the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce, and various clan associations. Ho moved to Singapore in 1925, where he was appointed principal of the Chinese High School (Huaqiao Zhongxue). He stayed at the school for three years before becoming a banker in 1928. Ho then fled to Chongqing in 1941 because of the Japanese onslaught, and returned to Singapore in 1949 to pursue careers in business and banking.27

A second group of students from Singapore arrived at Jinan Academy in 1910. Two notable personalities were Tan Ee Leong (Chen Weilong) and Hu Tsai Kuen (Hu Zaikun). Tan was born on 28 November 1897 in Yongchun, Fujian Province. He left China for the Nanyang in 1904 with his mother to join his father in Medan, Sumatra. There, he studied Chinese, but transferred to Jinan in 1910. At the Academy, Tan frequently consulted his senior, Lee Kong Chian, on mathematical problems. During the 1911 Revolution, Tan moved to Penang, where he studied English at the Anglo-Chinese School and took supplementary lessons in Chinese. In 1914, he followed his father to Singapore, where he enrolled at the Anglo-Chinese School there for his middle school education. Upon graduating in 1918, he worked in various banks and businesses. From May 1939 to February 1941, Tan served as the secretary of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce at Lee Kong Chian’s behest, as Lee was then the head of the Chamber.28 Tan reprised this appointment from 1960 to 1964. He retired from banking and business in 1964.29 As for Hu Tsai Kuen, while better known as the father of Richard Hu, the former Finance Minister of Singapore, he was a prominent personality in his own right. Born in Singapore during 1895, Hu Tsai Kuen was a Hakka. He studied in Anglo-Chinese School during the day and took Chinese lessons at Eng Sing 应新 School at night. Hu then transferred to Tao Nan because he wanted to attend Jinan, and he arrived at the Academy in 1910. He subsequently studied medicine at the University of Hong Kong from 1915 to 1921, after which he returned to Singapore in 1922. He set up the Nanyang Clinic on the island, where he practised Western medicine. Hu became well-known for his participation in the activities of the Overseas Chinese Association, which was established in 1942 during the Japanese Occupation with the backing of Shinozaki Mamoru. The Association’s initial intention was to save Chinese lives, but it was forced to spearhead the campaign that raised the notorious $50 million “donation” demanded by the Japanese military authorities. Hu then took part in the Endau scheme to transfer Chinese from Singapore to Johor in 1943, and was in charge of medical and health issues. He was an active member of the Hakka community in Singapore, and was also a patron of the arts during the 1950s.30

These students benefited from a modern education at Jinan. The Academy was modelled on the Japanese educational system, which featured nine years of elementary-standard schooling (divided into lower and upper levels) and five years of middle-school education.31 As such, there were two middle-school classes and four upper-elementary classes at Jinan. The medium of instruction was not standardized Mandarin, but instead depended on the respective languages of teachers. More significantly, the syllabi were hardly China-centric. Jinan’s administrators placed heavy emphasis on foreign languages, which encompassed not only reading but also translation work, conversational skills, and writing. Students similarly benefited from History and Geography lessons which featured case studies based on places beyond China’s shores (refer to the sample syllabi in tables A–C).32

Jinan Academy was closed amidst the turmoil of the 1911 Revolution which saw the end of Qing rule. The underlying cause was that the students cut their queues as early as fall 1910 after being exposed to revolutionary sentiment. The queue was a symbol of one’s loyalty to the Qing imperial court. As such, during the fighting in 1911, the provincial governor gave the order that those without queues were to be treated as revolutionaries. Fearing for their lives, most of the students returned to the Nanyang, with a small group fleeing to Shanghai. Others made their way to Wuchang 武昌, where the Revolution had first broken out, to participate in the fighting on the revolutionary side.33 Scholars have previously highlighted the financial contributions of Chinese migrant communities towards political movements in China.34 Yet migrants actually sacrificed limb and life for the revolutionary cause.

Revival and Expansion, 1918–1936

Classes at Jinan began again on 1 March 1918 after the renowned educator, Huang Yanpei 黄炎培, pushed for the institution’s revival. He did so upon returning to China from a fact-finding mission in the Nanyang. He was convinced that Chinese migrants and their descendants should be encouraged to study on the mainland. Nanjing was once more the location for the institution, which was named “Jinan School” (Jinan Xuexiao).35

This period featured a prominent Nanyang connection in Jinan’s history. For example, the school established a research institute to study the Nanyang. By 1927, Jinan was based in Shanghai after moving there during 1923 and 1924. Zheng Hongnian , who had been the first principal of Jinan Academy (1906–1909), returned to head Jinan in 1927 and made the decision on 13 June that year to expand the school’s activities. He added a research dimension to Jinan by founding the Nanyang Cultural and Educational Affairs Bureau . This was officially inaugurated in September 1927, the same month that the school was upgraded to the status of a national university. Zheng appointed himself as the Bureau’s first head, an indication that this research institute was a top priority.36 The establishment of the Bureau also constituted the institutional beginning of the Chinese-language track of Southeast Asian studies. The significance of this move was two-fold. Firstly, there had been no prior systematic attempt by scholars in China to conduct research on the Nanyang. Secondly, this move took place several decades before the North American contribution towards research on Southeast Asia.37

The formation of the Bureau represented the culmination of Chinese intellectual interest in the Nanyang, which had been partly influenced by Japanese research on the “Nanyo,” the Japanese equivalent of the Chinese “Nanyang.” Liu Hong has suggested that the advent of Nanyang studies at Jinan could therefore be traced back to the “South Seas Fever” in Japan as early as the first decade of the 20th century.38 My research has convinced me otherwise. The pre-First World War notion of the “Nanyo” in fact referred to Micronesia in the South Pacific, the islands seized by the Japanese from the Germans in 1914. The term did not at first refer to Southeast Asia. It was only after World War I that the concept of the “Nanyo” came to resemble more closely that of the “Nanyang.” Shimizu Hajime has suggested that this was due to Japanese economic penetration into Southeast Asia during the First World War.39 The Nanyo Kyokai (South Seas Association), founded during the war years, played a significant role in equating the Nanyo with Southeast Asia. Its activities encompassed the systematic training of experts and accumulation of information. It was supported by eminent Japanese, including nobility and businessmen, with governmental backing.40 Mark Peattie has also observed that during the 1920s, there emerged a division between the “Inner South Seas” (Uchi Nanyo), Micronesia, and the “Outer South Seas” (Soto Nanyo), Southeast Asia. He has further noted that the Japanese interest in the Nanyo gradually declined during the 1920s, when Nanyang studies began to emerge in China at Jinan. It was only during the 1930s that Japan began to rekindle its interest in the region due to the revival of Japanese commerce and the rise of imperialist ambitions.41

The Nanyang connection was also evident from the visit of the Jinan football (soccer) team to the region in 1928. The team famously won the Kiangnan Inter-collegiate Athletic Association League nine times between 1927 and 1937. In spring 1928, Zheng Hongnian decided to send the Jinan football players to the Nanyang for a series of friendly matches. The objective of the trip was to raise the school’s profile in the Nanyang in light of recent developments such as the achievement of university status and the founding of Nanyang studies at Jinan. Singapore was a key destination during the tour, which took place from March to June 1928. Other destinations included Saigon (Vietnam), Bangkok (Siam/Thailand), and several locations on the Malay Peninsula (Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh, Penang, Kelantan, and Trengganu).42 The official Jinan narrative does not, however, mention that this tour provided the impetus for the beginnings of an alumni association based in Singapore. While the organization was subsequently registered only in 1941, the informal gathering of Jinan alumni on the island could be traced back to 1928.43 The Jinan football team’s visit rekindled interest in maintaining links with the school among former students like Lee Kong Chian.

There continued to be students from Singapore at Jinan throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. These students travelled between China and the Nanyang. Many of them were born on the mainland, first migrating to the Nanyang before returning to China to study at Jinan. Upon graduating from the school, they headed to Singapore and played important roles in the Chinese community on the island. Two examples were Sheng Peck Choo 盛碧珠 and Liu Kang Both of them were born in Fujian Province in China, Sheng in Quanzhou 泉州 (1912) and Liu in Yongchun (1911). Sheng attended elementary and middleschool in China. This included a stay at Jimei 集美 School, which had been established by the famous Singapore philanthropist, Tan Kah Kee, to train teachers. Sheng then worked as a teacher before pursuing a university education with Jinan’s Education Department from 1932 to 1935. Upon graduation, she taught at a village school in China before leaving for Singapore in 1937 to join her husband and to work as a teacher there. She joined Chung Hwa Girls’ School in 1939, and subsequently rose to become its principal in 1955. She headed the school till her retirement in 1977.44 As for Liu Kang, he spent a substantial portion of his childhood (1917–1926) in Malaya because his father was a rubber merchant there. He then pursued a middle-school education at Jinan for a year (1926–1927) before switching to art classes at the Shanghai College of Fine Arts He furthered his studies in Paris from 1929 to 1933, after which he worked as a professor at the Shanghai College of Fine Arts from 1933 to 1937. Liu subsequently moved to Singapore and taught art at several schools. He went into hiding in Muar (Malaya) when the Japanese conquered the island. Thereafter, Liu became a famous painter in Singapore and was one of the pioneers of the Nanyang style of painting. This was a blend of both Western and Chinese methods, and it featured Nanyang subjects.45

War and The Move South, 1937–1942

After the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in August 1937, Jinan was forced to move its campus to the International Settlement, where the school stayed until 1941. The official Jinan narrative describes these years as the “Isolated Region” (gudao) period of the institution’s history because the school was isolated from the rest of “Free China.”46 But this narrative neglects to mention that Jinan was also cut off from the Nanyang after the invasion of Shanghai. The centre of gravity in the Nanyang connection therefore shifted to the region itself. Singapore constituted the heart of the Nanyang connection until the fall of the island to the Japanese in February 1942. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, Singapore became the main base for the field of Nanyang studies with the founding of the South Seas Society (Nanyang Xuehui) in 1940. Secondly, a Jinan alumni association was officially registered in Singapore in 1941.

Wang Gungwu has rightly stated that the South Seas Society’s founders “wrote very much in the shadow of the Nanyang Research Institute of Chi-nan (Jinan) University in Shanghai.”47 Indeed, the full Chinese version of the Society’s name was “Zhongguo Nanyang Xuehui” (China South Seas Society).48 However, while the intellectual lineage of the South Seas Society could be traced back to China, the “cradle for its initial development” was located in Singapore.49 Editors of the Sin Chew Jit Poh , a Chinese newspaper on the island, played a particularly important role in the birth of the Society. The organization was founded by eight scholars on 17 March 1940 at the Southern Hotel in Eu Tong Sen Street, Singapore. Five of the six who were actually present at this first meeting were linked to the Sin Chew Jit Poh. These five were also the majority in the seven-member inaugural council. They were: Guan Chupu (Kwan Chu Poh), Yu Dafu (Yue Daff), Yao Nan (T.L. Yao/Yao Tseliang/Yao Tsu Liang), Xu Yunqiao (Hsu Yun Tsiao/Hsu Yun-Tsiao/Hsu Yun-ts’iao), and Zhang Liqian (Chang Lee Chien/Chang Li-chien).50

Two co-founders who did not attend the inaugural meeting were Liu Shimu (Lou Shih Mo/Liu Shih-Moh) and Li Changfu (Lee Chan Foo/Lee Chang-foo). Liu resided in Penang, and had left China for the Nanyang in 1938 due to the upheaval caused by the Sino-Japanese War. Li was absent because he was in Shanghai at the time. The backgrounds of these two men shared a common denominator with Yao Nan’s profile: they all worked for the Nanyang Cultural and Educational Affairs Bureau at Jinan before establishing the South Seas Society.51 This reflected the Society’s connection to the China-based field of Nanyang studies. The backgrounds of Liu and Li further indicated a Japanese component. Liu was born during 1889 in Xingning , Guangdong province, while Li was born during 1899 in Jiangsu province. Liu was partly educated in Japan because of the availability of Economics courses in Japan on the Nanyang. These courses reflected a NanyoNanyang link. Liu then joined the Nanyang Cultural and Educational Affairs Bureau in February 1928 as head of the cultural affairs section. He subsequently headed the Bureau from June 1928 to 1933. Similarly, Li joined the Bureau in 1927 as an editor before leaving for Japan in 1929, where he stayed for two years. In Japan, Li learnt Japanese and English, after which he returned to work at the Jinan Bureau.52

As for Yao Nan, he was born in Shanghai during 1912, and developed an interest in the Nanyang during his youth. He felt that Chinese scholars needed to pay more attention to the region because the Chinese scholarly contribution had been lagging behind that of European writers. He enrolled in the Nanyang Middle School at the age of 15. Yao then pursued his interest in Nanyang studies by working as an English translator with the Nanyang Cultural and Educational Affairs Bureau at Jinan from August 1929. Yao later became the first head of the South Seas Society by virtue of his appointment as the Honorary Secretary, which was the highest-ranking position at the time. Amidst the Japanese onslaught on Malaya and Singapore, however, he fled to the Chinese war-time capital of Chongqing in 1941 and did not re-settle in Singapore after the end of the Second World War.53

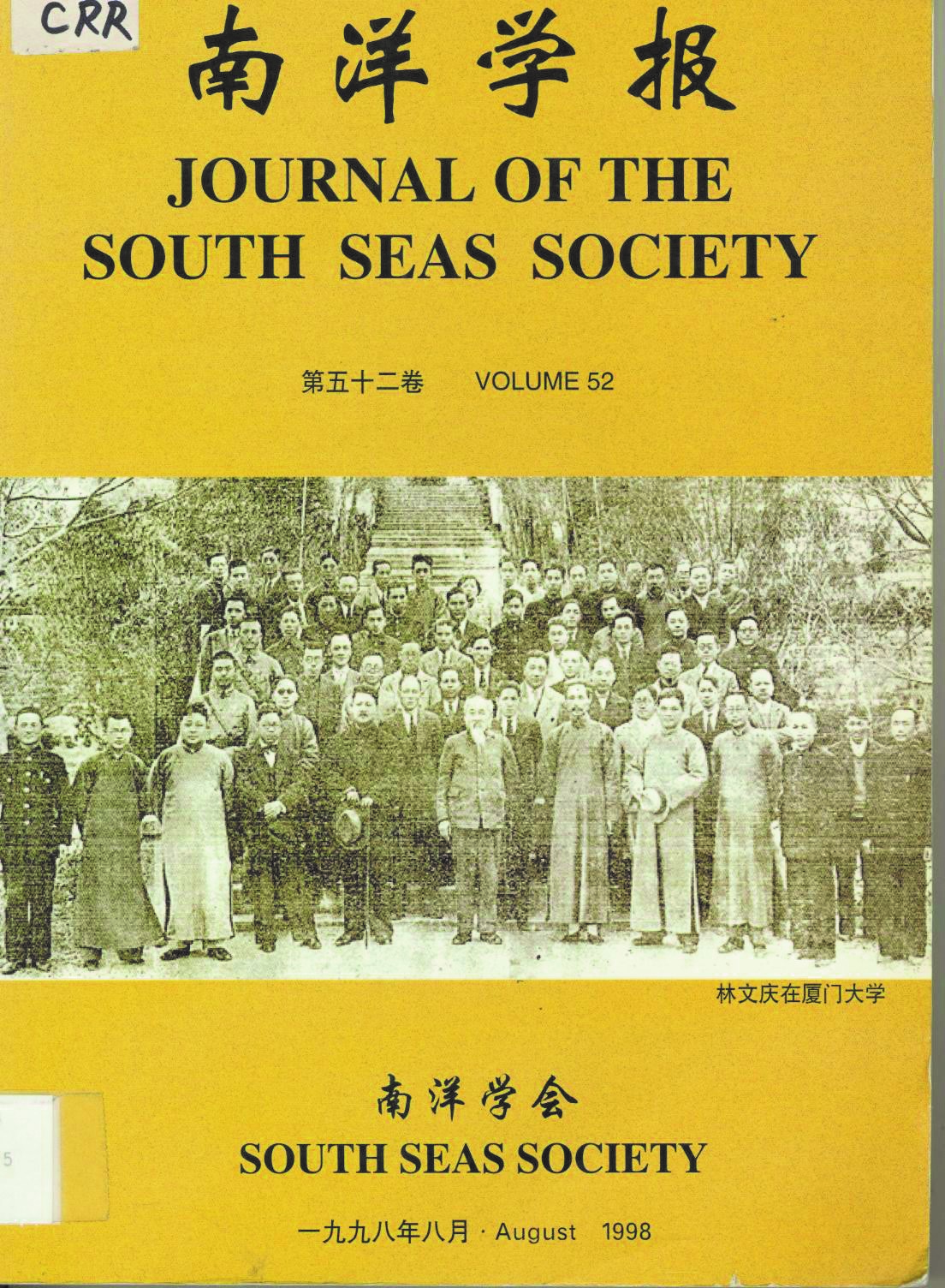

The activities of the South Seas Society were halted by the Japanese invasion of Singapore. Despite its short war-time existence, the Society nevertheless played an instrumental role in the development of Nanyang studies. It was the first Nanyang-based organization specializing in research on the region. This represented a new approach of understanding the Nanyang from the region’s perspective, without repudiating the debt owed to the China-based intellectual tradition. The Society’s flagship periodical, the Journal of the South Seas Society (Nanyang xuebao), broke new ground by being the first scholarly journal in the Nanyang to study the region. It was possibly also the oldest Chineselanguage academic journal in the area.54 The publication of the Journal and other Society activities resumed during the post-Second World War period.55

There was, additionally, overlapping membership between the South Seas Society and another organization with links to Jinan. This was the Singapore Jinan Alumni Association. Lee Kong Chian, for example, was a member of both organizations and a key sponsor of their activities.56 Although the move to found the Singapore Jinan Alumni Association began in 1940 with the submission of its registration application, the organization officially came into being only on 23 April 1941, when it was registered. It was initially known as the “Chi-Nan Alumni Association (Singapore).”57 There were about 10 founding members, one of whom was Lee Kong Chian. Hu Tsai Kuen was the founding Chairman and Lim Pang Gan was the inaugural Treasurer. The Association initially rented the third floor of 72 Robinson Road to serve as its headquarters.58

The choice of the Association’s original Chinese name, “Luxing Jinan Xiaoyouhui”, was significant because it was trans-regional, linking China and the Nanyang.59 The first character, “lu” 旅, implied that the organization’s location in Singapore was temporary and that there was thus no repudiation of the linkage with China. Yet the second character, “xing” 星, was an abbreviation for Singapore and an implicit acknowledgement of the Nanyang connection. The organization was also known as the “Jinan Xiaoyouhui,” and not “Jinan Daxue Xiaoyouhui” (Jinan University Alumni Association), because its membership comprised graduates of earlier nonuniversity incarnations of Jinan like Jinan Academy (1906- 1911).60 The Association’s activities came to a standstill with the fall of Singapore in February 1942. When it was revived in 1947 by Lim Pang Gan, it became known as the “Singapore Jinan Alumni Association” (Xinjiapo Jinan Xiaoyouhui).61

While the inaugural version of the Singapore Jinan Alumni Association survived for only a short time before the Japanese conquest of Singapore in 1942, its existence was significant. The organization was one of the earliest Jinan alumni associations worldwide, and was possibly the oldest in the Nanyang.62 The official coordinating body at Jinan University was not established until 25 December 1992. Furthermore, the founding of the Singapore-based organization represented the culmination of close links between the alumni on the island. Informal gatherings of these Jinan graduates had indeed begun as early as 1928, being prompted by the Jinan football team’s tour of the Nanyang. The reason for the delay in registering the Association has not been explained in the organization’s publications.63 It could have been because there had been insufficient alumni in Singapore or inadequate financial resources to support an alumni association until the 1940s.64 Another plausible theory is that the Singapore alumni had not seen the need to formally establish such a body until the isolation of Jinan following the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in 1937. The siege of the school meant that there was now a need to keep the memory of their alma mater alive south of China, in the heart of the Nanyang.

Concluding Remarks

In recent decades, approaches to the issues of Chinese identity and the global role of China have tended to emphasize either economic or cultural linkages between China and Chinese communities in other countries.65 Yet such notions as “Greater China” and “Cultural China” have presented an imbalanced interpretation of the Chinese world because they have overemphasized the mainland’s importance. My article has furnished a new perspective through an analysis of the trans-regional experiences of Jinan intellectuals and students like Lee Kong Chian. I have thus offered a more holistic conceptualization of the Chinese world, one which has hitherto been absent from the historiographies of modern China and Chinese migration.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

NOTES

-

Leander Seah, “Conceptualizing the Chinese World: Jinan University, Nanyang Migrants, and Trans-Regionalism, 1900–1941” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2011), https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3462170/. ↩

-

I have excluded Chinese works on education from this overview of the historiography on modern China because they lack analysis: Marianne Bastid, Educational Reform in Early Twentieth Century China, trans. Paul J. Bailey (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan, 1988), xvi. ↩

-

Three notable exceptions have been: Yeh Wen-Hsin, The Alienated Academy: Culture and Politics in Republican China, 1919–1937 (Cambridge, Mass.: The Harvard University Asia Center, 1990) (Call no. RCLOS 378.51 YEH); Ruth Hayhoe, China’s Universities, 1895–1995: A Century of Cultural Conflict (New York: Garland Publishing, 1996) (Call no. RUR 378.510904 HAY); Thomas D. Curran, Educational Reform in Republican China: The Failure of Educators to Create a Modern Nation (Lewiston, New York: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2005) ↩

-

For further analysis of post-1970s scholarship on modern China, refer to: Hans van de Ven, “Recent Studies of Modern Chinese History,” Modern Asian Studies 30, no. 2 (May 1996), 226. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “Maritime China in Transition,” in Maritime China in Transition 1750–1850, ed. Wang Gungwu and Ng Chin-keong (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004), 4. ↩

-

Ien Ang, On Not Speaking Chinese: Living Between Asia and the West (London: Routledge, 2001). For a discussion of the theoretical implications of the term, “diaspora,” see Kim D. Butler, “Defining Diaspora, Refining a Discourse,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 10, no. 2 (Fall 2001), 189–219. ↩

-

Adam McKeown, Chinese Migrant Networks and Cultural Change: Peru, Chicago, Hawaii, 1900–1936 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001), 84–85. ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, China and the Chinese Overseas (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991) (Call no. RSING 327.51059 WAN); Wang Gungwu, “A Single Chinese Diaspora?” in Diasporic Chinese Ventures: The Life and Work of Wang Gungwu, ed. Gregor Benton and Hong Liu (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004), 157. (Call no. R 950.049510092 DIA) ↩

-

Lynn Pan, ed., The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas (Singapore: Published for the Chinese Heritage Centre by Archipelago Press and Landmark Books, 1998), 14–15. (Call no. RSING 304.80951 ENC) ↩

-

Zhu Guohong has rightly highlighted the localized focus of the extant scholarship, but his solution is still Sino-centric since it is based on understanding migrant activity as emigration from China. Refer to Zhu Guohong 朱国宏著, Zhongguo de haiwai yimin: yixiang guoji qianyi de lishi yanjiu 中国的海外移民: 一项国际迁移的历史研究 [Chinese emigration: A historical study of the international migration] (Shanghai 上海: Fudan Daxue Chubanshe 复旦大学出版社, 1994), 5. (Call no. Chinese RCO 909.04951 ZGH) ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, Don’t Leave Home: Migration and the Chinese (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 2001), 291, 293. (Call no. RSING 304.80951 WAN) ↩

-

For example, enrolment at Jinan Academy (Jinan Xuetang), the school’s earliest incarnation, peaked at 240 in 1911: Jinan Daxue Xiaoshi Bianxiezu, Jinan xiaoshi 1906–1996 校史 1906–1996 (Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Chubanshe, 1996), 5–7. ↩

-

I have previously examined the origins of the name, “Nanyang,” and the region’s geographical boundaries: Leander Seah, Historicizing Hybridity and Globalization: The South Seas Society in Singapore, 1940–2000 ([n.p.], 2007) (Call no. RSING 305.895105957 SEA); Refer also to Leander Seah, “Hybridity, Globalization, and the Creation of a Nanyang Identity: The South Seas Society in Singapore, 1940–1958,” Journal of the South Seas Society (Nanyang xuebao) 61 (December 2007), 134–51. ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, Community and Nation: China, Southeast Asia and Australia (St Leonards: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with Allen & Unwin, 1992), 29. (Call no. RSING 305.8951059 WAN) ↩

-

See Table 3 in Adam McKeown, “Global Chinese Migration, 1840–1940” (paper delivered at ISSCO V: the 5th Conference for the International Society for the Study of the Chinese Overseas, Elsinore (Helsingor), Denmark, 10–14 May 2004), 5. ↩

-

Jinan Daxue Xiaoshi Bianxiezu, Jinan xiaoshi 1906–1996, 4; “Muxiao xiaoshi” 母校校 母校校史, in Jinan xiaoshi, 1906–1949: Ziliao xuanji 暨南校史, 1906–1949 [Selected source material on history of Jinan University, 1906–1949], vol. 1, ed. Jinan Daxue Huaqiao Yanjiusuo (Institute of Overseas Chinese Studies, Jinan University) (Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Huaqiao Yanjiusuo, 1983), 3. ↩

-

Bastid, Educational Reform, 241; See also Hiromu Momose’s biography in Arthur W. Hummel, ed., Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period (1644–1912), vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1944), 781 (Call no. RCLOS 920.051 EMI); Wu Zixiu 吴子修, Xinhai xunnanji 新海寻南记 [Xinhai Searching for the South] ([n.p.:1916), 514–16. ↩

-

The economic dimension has been thoroughly analyzed in Yen Ching-Hwang’s book, Coolies and Mandarins: China’s Protection of Overseas Chinese during the Late Ch’ing Period (1851–1911) (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1985). (Call no. RSING 325.2510959 YEN) ↩

-

Zhou Xiao 周孝, Jinan yishi 逸逸史 (Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Chubanshe, 1996), 2. Zhou’s book is possibly the only work published by Jinan University Press that has not downplayed this important fact. ↩

-

For instance, Wee Tong Bao has examined the case of Singapore in her dissertation: “The Development of Modern Chinese Vernacular Education in Singapore – Society, Politics & Policies, 1905–1941” (master’s theses, National University of Singapore, 2001), 1, 14. ↩

-

Note that I have spelt “Oversea” according to the official name. For references, see, for example, “Reliving Lee Kong Chian,” AlumNUS 17 (March 1994), extracted from National University of Singapore Central Library Reference Office Personality Files Collection. Known as the “rubber king” during the 1950s, Lee was so respected that he even lectured on Southeast Asia at the Naval School of Military Government and Administration (based at Columbia University in New York City) at the invitation of law professor Philip C. Jessup. Lee had been stranded there while attending a rubber conference during the Pacific War: Tan Kok Kheng, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 24 September 1983, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:31 (National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000232); Schuyler C. Wallace, “The Naval School of Military Government and Administration,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 231 (January 1944), 29–33 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Chia Poteik, “Lee Kong Chian: Pay-Off for Perseverance,” Straits Times, 13 June 1962, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee had fond memories of his brief stay at Tao Nan. Indeed, his wedding ceremony was held there. ↩

-

Jinan Xuetang xianxing zhangcheng 暨南學堂現行章程 [The current constitution of Jinan Academy] (Nanjing: Jinan Xuetang, c. 1911), 13. ↩

-

Selected sources on Lee Kong Chian: Zhou Xiaozhong, Jinan yishi, 11–12; Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim Poh Hoon, 28 May 1981, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:32 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000003); Poteik, “Pay-Off for Perseverance”; “Li Guangqian boshi” in Xing ma renwu zhi 星马人物志 [Who’s Who in South East Asia], vol. 1 ed. Song Zhemei 宋哲美 (Xianggang 香港: Dongnan Ya yan jiu suo 东南亚研究所, 1969), 23–50 (Call no. Chinese RSING 920.0595 WHO); Zheng Bingshan, Li Guangqian zhuan (Beijing: Zhongguo Huaqiao Chubanshe, 1996), 17–20, 223–24; Quek Soo Ngoh, Lee Kong Chian: Contributions to Education in Singapore 1945–1965 (Singapore: National University of Singapore, 1986), 15–17 (Call no. RSING 370.95957 QUE); Chen Weilong , “Laotongxue jianjie,” in Jinan Xiaoyouhui xinhuisuo luocheng ji Xinjiapo kaibu yibai wushi zhounian jinian tekan [Souvenir publication on inauguration of new premises of the Chi-nan Alumni Association and 150th anniversary of the founding of Singapore) (Singapore: Jinan Xiaoyouhui, 1970), 37. Some of these sources furnish incorrect details. For example, Lee studied and taught at Yeung Ching School, and not “Yeung Chia” “Chung Cheng” or “Chongzheng” 崇崇正 Schools. ↩

-

Refer to the sources in the previous endnote. ↩

-

The first intake from Singapore was part of the fifth overall cohort (54 students) from the Nanyang. Refer to Lim Pang Gan, oral history interview by Tan Ban Huat, 10 May 1980, transcript and MP3 audio: 31:33 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000036); “Jinan biannian dashiji” Jinan jiaoyu 5 (December 1987), 82. ↩

-

Zhou Xiaozhong, Jinan yishi, 15–17; Lim Pang Gan, oral history interview by Tan Ban Huat; Lim Pang Gan, oral history interview by Tan Ban Huat, 10 May 1980, transcript and MP3 audio: 31:38 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000036); Lim Pang Gan, oral history interview by Chua Ser Koon, 20 October 1982, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:45 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000227); Lim Pang Gan, oral history interview by Chua Ser Koon, 20 October 1982, transcript and MP3 audio: 16:41 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000227); Xing Zhizhong , “‘Gancao laoren’ lao shezhang Lin Bangyan xiansheng” in Tongde Shubaoshe jiushi zhounian jinian tekan, ed. Tongde Shubaoshe Jiushi Zhounian Jinian Tekan Weiyuanhui (Singapore: Tongde Shubaoshe, 2000), 60–62; “He Baoren boshi” in Xingma renwuzhi, vol. 2 (Hong Kong: Dongnanya Yanjiusuo, 1972), 113–14. ↩

-

Tan was on very good terms with Lee Kong Chian, serving as the best man at Lee’s wedding in 1928. ↩

-

Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim Poh Hoon, 27 December 1979, transcript and MP3 audio: 32:08 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000003); Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim Poh Hoon, 27 December 1979, transcript and MP3 audio: 32:07 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000003); Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim Poh Hoon, 14 January 1980, transcript and MP3 audio: 31:05 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000003); Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim Poh Hoon, 14 January 1980, transcript and MP3 audio: 32:37 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000003); Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim Poh Hoon, 28 May 1981, transcript and MP3 audio: 26:37 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000003); Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim Poh Hoon, 28 May 1981, transcript and MP3 audio: 26:32 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000003); “Chen Weilong xiansheng” in Xingma renwuzhi, vol. 1 (Hong Kong: Dongnanya Yanjiusuo, 1969), 179–91; and Chen Weilong , Dongnanya huayi wenren zhuanlue (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1977), vi. None of these sources, however, provide the correct dates for Tan’s second stint as the Secretary of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, using the years “1958–1964” instead of “1960–1964”. I have therefore referred to the Chamber’s official record: Fangyan sihai: Xinjiapo Zhonghua Zongshanghui jiushi zhounian jinian tekan (Singapore: Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce & Industry, 1996), 99. ↩

-

Chen Weilong, “Qingmo Jinan huiyi zhier” in Jinan xiaoshi, 1906–1949: Ziliao xuanji, vol. 1, 98; ; Lim Pang Gan, oral history interview by Tan Ban Huat; Koh Soh Goh, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 24 October 1984, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:34 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000497); “The Doctor Who Had a Shot at Art,” Straits Times, 30 October 1984, 1; “Hakka Leader Dies After Illness,” Straits Times, 25 October 1984, 13 (From NewspaperSG); and Mamoru Shinozaki, My Wartime Experiences in Singapore (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1973), 32–33, 79–80. (Call no. RSING 959.57023 SHI) ↩

-

Chen Weilong, “Qingmo Jinan huiyi zhier” 99. ↩

-

Jinan Xuetang xianxing zhangcheng. ↩

-

Chen Weilong, “Qingmo Jinan huiyi zhier” 97, 102–3; Zheng Hongnian, “Guoli Jinan Daxue zhi baogao,” in Huaqiao jiaoyu huiyi baogaoshu ([n.p.], May 1930), 19; Jinan Gaojiaoshi Ziliaozu, “Jinan biannian dashiji” Jinan jiaoyu 5 (December 1987), 81–82; “[Jinan dili, Jinling] Yuan Shikai danu: ‘Jinan doushi xie gemingdang,” (accessed 30 May 2007) ↩

-

See, for example, Yen Ching-Hwang, The Overseas Chinese and the 1911 Revolution: With Special Reference to Singapore and Malaya (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1976), xviiixix, 90–91, 309. (Call no. RSING 301.451951095957 YEN) ↩

-

“Jinan biannian dashiji,” 82. ↩

-

Jinan nianjian 1929 (Chinan Annual 1929) (Shanghai: Guoli Jinan Daxue, 1929), n.p ↩

-

The Bureau was active, publishing various periodicals like Nanyang yanjiu 南洋研究研 and a monograph series. It also spearheaded the organization of academic conferences. One example was the large-scale 1929 Nanyang Huaqiao Jiaoyu Huiyi at Jinan, which featured 78 participants, of which 49 were from the Nanyang: “Jinan biannian dashiji,” 86. ↩

-

Liu Hong, “Southeast Asian Studies in Greater China,” Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia no. 3 (March 2003) ↩

-

Shimizu Hajime, “Southeast Asia as a Regional Concept in Modern Japan,” in Locating Southeast Asia: Geographies of Knowledge and Politics of Space, ed. Paul H. Kratoska, Remco Raben and Henk Schulte Nordholt (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2005), 87–88. (Call no. RSING 959 LOC) ↩

-

Mark R. Peattie, “Nanshin: The ‘Southward Advance,’ 1931–1941, as a Prelude to the Japanese Occupation of Southeast Asia,” in The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931–1945, ed. Peter Duus, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996), 198–99 (Call no. RSING 950.41 JAP); Hueiying Kuo, “Nationalism against its People? Chinese Business and Nationalist Activities in Inter-war Singapore, 1919–1941” (Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series no. 48, City University of Hong Kong, July 2003); J. Charles Schencking, “The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Constructed Consciousness of a South Seas Destiny, 1872–1921” Modern Asian Studies 33, no. 4 (October 1999), 792 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). Peattie indicates that the Nanyo Kyokai was founded in 1914, but Schencking states that this took place in January 1915. The actual date of establishment will be determined after further research and will be provided in my Ph.D. dissertation, Seah, “Conceptualizing the Chinese World.” ↩

-

Jinan nianjian 1929; and Ma Xingzhong, “Jinan Daxue yu Xinjiapo,” in Jinan Daxue bainian huadan, Xinjiapo Xiaoyouhui liushiwu zhounian (Singapore: Xinjiapo Jinan Xiaoyouhui Chuban Weiyuanhui, 2006), 30. ↩

-

Xing Jizhong, “Fengxian manhuai aixin gongchuang meihao weilai,” in Jinan Daxue bainian huadan, Xinjiapo Xiaoyouhui liushiwu zhounian, 1. ↩

-

While Sheng has stated that she retired in 1978, the school’s records indicate instead that this took place in 1977: Sheng Peck Choo, oral history interview with Ang Siew Ghim, 9 March 1995, transcript and MP3 audio: 30:49 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 001608); Sheng Peck Choo, oral history interview with Ang Siew Ghim, 9 March 1995, transcript and MP3 audio: 31:05 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 001608); Sheng Peck Choo, oral history interview with Ang Siew Ghim, 9 March 1995, transcript and MP3 audio: 31:08 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 001608); Sheng Peck Choo, oral history interview with Ang Siew Ghim, 9 March 1995, transcript and MP3 audio: 29:10 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 001608); Zhonghua Zhongxue chuangxiao bashi zhounian jinian tekan 中华中学创校八十周年纪念特刊 [Zhonghua Secondary School 80th Anniversary Souvenir Magazine, 1911–1991) (Singapore 新加坡: Zhonghua Zhongxue [该校], 1991), 41 (Call no. Chinese RCLOS 373.5957 ZHO). For additional biodata, see: Jinan Xiaoyouhui xinhuisuo luocheng ji Xinjiapo kaibu yibai wushi zhounian jinian tekan, 147. ↩

-

For a discussion of Liu’s Nanyang style, refer for example to Alicia Yeo, “Singapore Art, Nanyang Style,” BiblioAsia 2, no. 1 (April 2006), 4–11. I have also referred to numerous sources, including: Liu Kang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 9 April 1982, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:43 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000171); Liu Kang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 9 April 1982, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:48 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000171); Liu Kang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 16 November 1982, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:47 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000171); Liu Kang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 13 January 1983, transcript and MP3 audio: 27:49 (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 000171); “Untitled,” Straits Times, 3 February 1993, 3; and “Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man,” Straits Times, 31 March 2000, 102 (From NewspaperSG). Many sources provide incorrect dates for Liu Kang’s stay at the Shanghai College of Fine Arts because they do not take into account his studies at Jinan. The dates for his enrolment at Jinan can be found in: Jinan Xiaoyouhui xinhuisuo luocheng ji Xinjiapo kaibu yibai wushi zhounian jinian tekan, 149. ↩

-

Zhang Xiaohui, ed., Bainian Jinan shi 1906–2006 (Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Chubanshe, 2006), 91. ↩

-

Wang, China and the Chinese Overseas, 34. ↩

-

See the inaugural annual report, Journal of the South Seas Society 1, no. 1 (June 1940), 95 of the Chinese section. ↩

-

Gwee Yee Hean, “South Seas Society: Past, Present and Future” _Journal of the South Seas Societ_y 33 (1978), 32. ↩

-

For further details, refer to Seah, “Hybridity, Globalization, and the Creation of a Nanyang Identity.” ↩

-

Jinan xiaoshi 1906–1996, 38 and Table 7 on 325. ↩

-

For Liu’s biographical details, see Journal of the South Seas Societ_y 8, no. 2 (December 1952), especially 1–13 of the Chinese section; and Yao Nan 姚楠姚楠, Nantian yumo (Shenyang: Liaoning Daxue Chubanshe, 1995), 39. Concerning Li’s hometown, sources differ: it was either Dantu 丹徒 or Zhenjiang see Bianji suoyu,” _Journal of the South Seas Society 1, no. 2 (December 1940), 3 of the Chinese section; Yao Nan, Nantian yumo, 39; and Chen Daiguang , “Li Changfu xiansheng zhuanlue” , in Li Changfu , Nanyang shidi yu huaqiao huaren yanjiu (Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Chubanshe, 2001), 1–2. ↩

-

“Yidai caizi Nantian Jiulou qi ‘hui’: Nanyang Xuehui 54 nian,” Lianhe zaobao, 10 April 1994; Yao Nan, Nantian yumo, 39–40; Yao Nan, Xingyunyeyuji (Singapore: Singapore News & Publications Ltd. [Book Publications Dept.], 1984), 2. ↩

-

1940 annual report, Journal of the South Seas Societ_y 1, no. 1 (June 1940), 95 of the Chinese section; and the “Fakan zhiqu” (Foreword) in the same _Journal of the South Seas Society nos. 1–2 of the Chinese section. ↩

-

For post-war activities, refer to Seah, “Historicizing Hybridity and Globalization.” ↩

-

Lee was a South Seas Society member from 1946 till his death in 1967, and was also a founding member of the Singapore Jinan Alumni Association. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Government Gazette 76, no. 55 (2 May 1941), 933. ↩

-

He Baoren , and Lin Bangyan , “Jinan Xiaoyouhui chuangli shimoji” , in Jinan Xiaoyouhui xinhuisuo luocheng ji Xinjiapo kaibu yibai wushi zhounian jinian tekan, 89; Xing Jizhong, “Fengxian manhuai aixin gongchuang meihao weilai,” 1; and Ma Xingzhong, “Jinan Daxue yu Xinjiapo,” 30-32. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 933. ↩

-

Interviews conducted in Mandarin with Xing Jizhong on 25 June 2007 and 16 August 2007. Also known by his penname, “Xing Zhizhong” 邢致邢致 , Xing is a famous writer in Singapore who was born in China and who studied at Jinan University from 1943 to 1947. At the time of my interviews with him, he had just relinquished his position as the head of the Singapore Jinan Alumni Association after five years of leadership. He joined the organization in 1982 as its Assistant Secretary, was the Secretary from 1984 to 2002, and became the head in 2002. He is possibly the Association’s most senior surviving member. ↩

-

Refer to the sources in endnote 58. ↩

-

See endnote 60. ↩

-

The founding members have also passed away and are therefore not available for interviews. Oral interviews which were recorded before their demise do not contain information on this issue. ↩

-

See endnote 60. ↩

-

Wang, Don’t Leave Home, 91; Tu Wei-Ming, ed., “Cultural China: The Periphery as the Center,” in The Living Tree: The Changing Meaning of Being Chinese Today (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), 1–34. (Call no. RSING 306 LIV) ↩