Reviving the Silk Road and the Role of Singapore

The possibility of the Middle East emerging as a new economic giant in this new century has given rise to romantic notions of a “New Silk Road” that would link Asia and the Middle East. While China’s ancient capital Chang’an had served as the point of departure for travellers using the Silk Road, Singapore could perhaps be the modern-day Chang’an and be the bridge between Asia and the Middle East.

As the Middle East and Asia realise the benefits to be gained from collaboration, the prospects of reviving ties between the two regions have grown more than ever before. The possibility of the Middle East emerging as a new economic giant in this new century has given rise to romantic notions of a “New Silk Road” that would link Asia and the Middle East in a revival of the old trans-regional arc of mutual prosperity. While China’s capital Chang’an had served as the point of departure for travellers using the Silk Road, today, Singapore could perhaps be the modern-day Chang’an and build the bridge between Asia and the Middle East as both Arabs and Asians rediscover each other.

Singapore and the Middle East: Increasing Mutual Cooperation

For Singapore, serious engagement with the Middle East began in 2004 when Singapore’s Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong made a series of high-level official visits to Middle East.1

In June 2005, Singapore also hosted the inaugural AsiaMiddle East Dialogue (AMED), providing an unprecedented platform for countries from the two regions to come together to discuss issues and areas of mutual concern.2 AMED enabled policy makers, intellectuals and businessmen to discover the huge opportunities for cooperation and led to several bilateral agreements between countries in the two regions. As a follow up, the Singapore Business Federation launched the Middle East Business Group in March 2007. It set out two objectives: to foster strong ties between business chambers and companies from both sides and to provide consultations for local companies with business interests in the Middle East.3

New Markets and Businesses

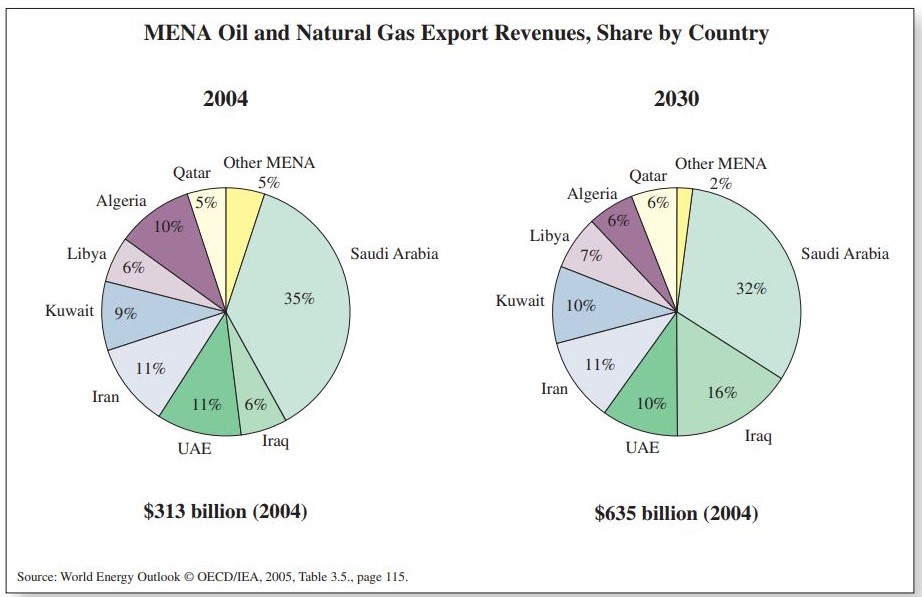

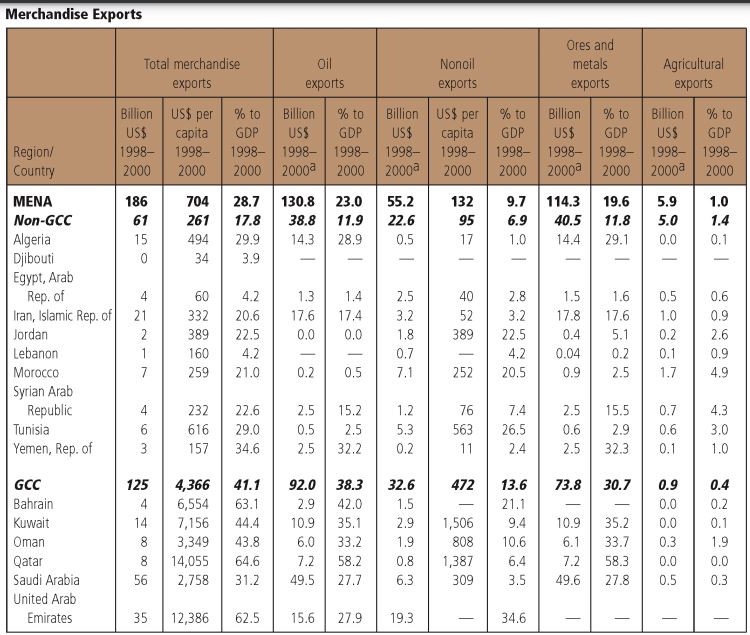

Many Middle Eastern economies, especially the Gulf Cooperation Council states (GCC) - comprising Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and Oman - are witnessing an unprecedented increase in revenues because of sustained oil prices over the last few years. Together with Iran, the Gulf States account for 84% of the world’s known recoverable oil reserves.4 In 2006, world oil demand also grew by 0.9%, hence benefiting the oil producers.5 In a recent study done by financial investment company Arcapital, it was reported that for the past five years, the GCC’s collective annual current-account surplus had risen from US$25bn to over US$200bn.6 The study revealed that official reserves had doubled from US$51bn in 2002 to US$98bn in 2007, and were expected to reach US$100bn by 2008.7 Unfortunately, while this has positive implications on the local economy and social life of the people, it has the potential to bring about more conflicts and instability to the region. Indeed, in the last 25 years, many wars in the regions were fought over oil.8 Cases in point would be the Iraq-Iran war from 1980 to 1988, the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990 and the war in Iraq to liberate Kuwait in 1991. Even the invasion of Iraq in 2003 could possibly be construed as being motivated by the desire to secure oil resources in Iraq.

Besides the cash surplus generated from the energy industry, one should take note of the rise of a new business elite in the Gulf States. Members of this group have studied in well-known Western Universities and have good business knowledge. This new elite comprises youths who are equipped with capital, knowledge and ambition and are eager to move away from the energy business. Although it is too early to speculate that more of these elite’s investments would find its way to Asian markets, especially China, Singapore, India and Malaysia, it would certainly be interesting to watch an important group of these investors daring to take risks in their homeland by investing in new economic sectors such as tourism, bio-industry and real estate. It is possible that these young businessmen possess more decisiveness in taking charge of their wealth and the capacity for growth. Current geopolitical developments are also in favour of such a shift. The Middle Eastern governments are also seeing the need to support and establish the policy framework for these elite to embark on new businesses.

What Makes Singapore the Ideal Partner?

With just a surface area of 692.7km, Singapore sets an exceptional success story. On the world map Singapore is but a tiny red dot. Nevertheless, despite having no natural resources such as oil and gas, the island is today one of the world’s most developed nations. Good governance, good planning and strong adherence to the rule of law are just some of the contributing factors to the success story.

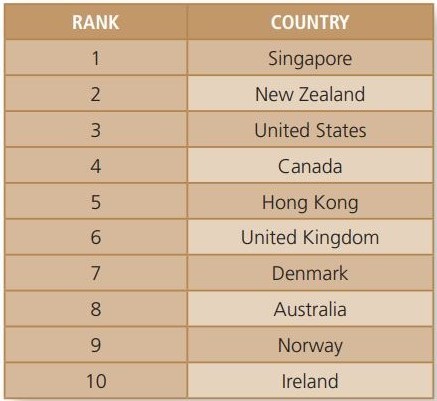

Today the name Singapore is synonymous with sophisticated infrastructures, cleanliness, efficiency, good governance and many other factors that have contributed to the success of the country. Such factors have enabled the country to attract more business from all over the world. To cite one example, the World Bank report has ranked Singapore as the world’s easiest place to do business. As Table 1 shows,9 Singapore is ranked first, ahead of several countries with long business traditions and capabilities such as the United States and Hong Kong.

TABLE 1: WORLD’S EASIEST PLACE TO DO BUSINESS

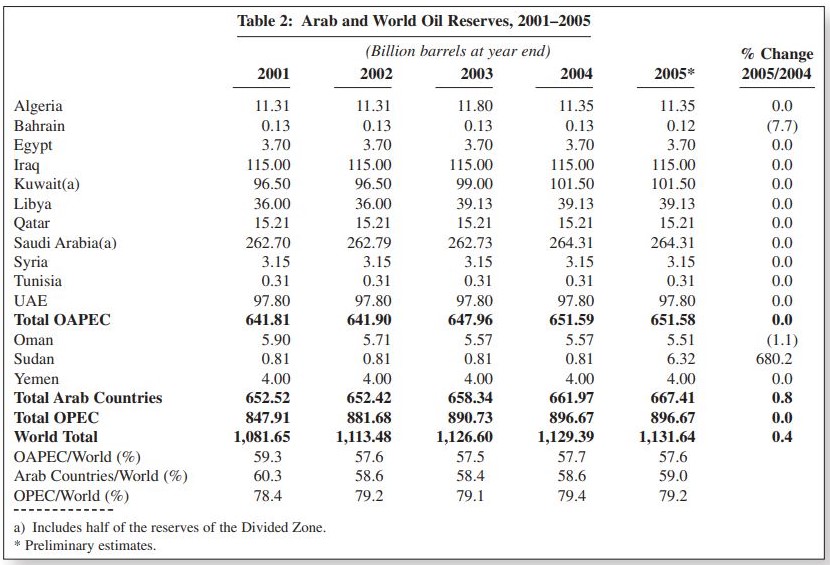

Singapore has been strong in industries such as oil refining, ship repairing and electronic. Recently the country is also moving towards non-electronic industries such as the bio-chemicals and finance.10 A good indication of the country’s economic power is the consistent surplus of exports over imports as indicated in Table 2.11

Arab and World Oil Reserves, 2001–2005. Source: Arab Oil and Gas Directory. (2007). Paris: Arab Petroleum Research Center.

Arab and World Oil Reserves, 2001–2005. Source: Arab Oil and Gas Directory. (2007). Paris: Arab Petroleum Research Center.

One may contend that a rich country is not necessarily a developed one. However, Singapore is different: the country does not have any natural resources. Indeed, the country’s exports comprised mainly electronic products, scientific instruments, crude material, chemical products and technology.12 Singapore companies are involved in big projects in many countries in Asia or Middle East.13

The New Silk Road

The Silk Road or the Silk Route is the most well known trading route of ancient Chinese civilisation. It was discovered more than 2,000 years ago by Chang Chi’in, a Chinese traveller who had crossed China on a secret military mission that would later help China discover Europe and the origins of the Silk Road.14 Travelling more than 7,000 kilometres, horse caravans crossed China, Central Asia, and the Middle East, carrying cosmetics, rare plants, medicines, aromatic items, spices woods, books and others.15 However, silk was the most important product because the Romans and Arabs appreciated it. The Romans desired it to the extent that during the times when demand for silk increased substantially, Rome had to pay for it with vast amounts of gold.16 Both the Silk Road and China achieved its greatest glory during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), which is generally regarded as China’s “golden age.”17 Its capital Chang’an, “the Rome of Asia”, which served as the point of departure for travellers using the Silk Road, was one of the most cosmopolitan cities then.18

Singapore would perhaps perform the task of Chang’an in this modern era. Singapore enjoys a good reputation among its neighbours and the international community.

Its sophisticated infrastructures, strategic location and favourable business environment are but some of the several factors that would enable Singapore to take the lead in reconnecting Asia and the Middle East. Indeed, all the developments- (including political, economic and social) forecast a revival of the Silk Road. History has always played a role in linking disparate regions, as seen from the trading links between Middle East via Arab traders in Singapore.19 It is these established networks that enable Singapore and the Middle East to enhance their cooperation and exchanges towards a more vital and dynamic relationship.

Researcher

National Library

REFERENCES

Arab Oil & Gas Directory (2007). (Call no. RBUS 338.272809174927 AOGD)

Department of Statistics, Yearbook of Statistics Singapore (Singapore: Department of Statistics, 2007). (Call no. RSING 315.957 YSS)

Derek da Cunha, ed., Singapore in the New Millennium, Challenges Facing the City-State (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2002). (Call no. RSING 959.57 SIN-[HIS])

“Foreign Policy: Countries/Regions: Middle East – Bilateral Relations” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed 21 January 2008, https://www.mfa.gov.sg/SINGAPORES-FOREIGN-POLICY/Countries-and-Regions.

Hossein Askari, Middle East Oil Exporters, What Happened to Economic Developments? (London: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2006). (Call no. RBUS 338.956 ASK)

L. W. C. van den Berg, Le Ḥadhramout Et Les Colonies Arabes Dans L’archipel Indien (Batavia: Imprimerie du Gouvernement, 1886). (Call no. RRARE 325.25309598 BER; microfilm NL7400)

“Near East Meets Far East: The Rise of Gulf Investment in Asia,” accessed 21 January 2008, https://www.arcapita.com/.

Peter Hopkirk, “The Rise and Fall of the Silk Road,” in Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia (London: John Murray, 1980). (Call no. RUR 931 HOP)

“SBF Launches Middle East Business Group To Boost Business Ties Between Singapore and the Middle East,” Singapore Business Federation, 26 March 2007, accessed 21 January 2008, https://www.sbf.org.sg/what-we-do/internationalisation.

The Gulf: Future Security and British Policy (Abu Dhabi: Reading: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, 2000)

“Why Singapore: Singapore Rankings” Economic Development Board, accessed 22 January 2008, http://www.edb.gov.sg/edb/sg/en_uk/index/why_ singapore/singapore_rankings.html.

NOTES

-

“Foreign Policy: Countries/Regions: Middle East – Bilateral Relations” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed 21 January 2008, https://www.mfa.gov.sg/SINGAPORES-FOREIGN-POLICY/Countries-and-Regions. ↩

-

“Foreign Policy.” ↩

-

Singaporean companies were very active in various range of businesses in the Middle East, including petrochemical distribution rights, hotel development, water desalination, investment in petrochemical olefin projects, investment in food manufacturing plant, e-government project, e.g. e-judiciary and e-trade projects, investment in food manufacturing plant, sale of automotive parts, stationery and printing consumables, export of work products, oil and gas parts and automotive parts as well as oil, petrochemical trade. “SBF Launches Middle East Business Group To Boost Business Ties Between Singapore and the Middle East,” Singapore Business Federation, 26 March 2007, accessed 21 January 2008, https://www.sbf.org.sg/what-we-do/internationalisation. ↩

-

The Gulf: Future Security and British Policy (Abu Dhabi: Reading: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, 2000), 46. ↩

-

Arab Oil & Gas Directory (2007), 606. (Call no. RBUS 338.272809174927 AOGD) ↩

-

“Near East Meets Far East: The Rise of Gulf Investment in Asia,” accessed 21 January 2008, https://www.arcapita.com/. ↩

-

“Near East Meets Far East.” ↩

-

Hossein Askari, Middle East Oil Exporters, What Happened to Economic Developments? (London: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2006), 36–37. (Call no. RBUS 338.956 ASK) ↩

-

“Why Singapore: Singapore Rankings” Economic Development Board, accessed 22 January 2008, http://www.edb.gov.sg/edb/sg/en_uk/index/why_ singapore/singapore_rankings.html. ↩

-

Derek da Cunha, ed., Singapore in the New Millennium, Challenges Facing the City-State (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2002), 46. (Call no. RSING 959.57 SIN-[HIS]) ↩

-

Department of Statistics, Yearbook of Statistics Singapore (Singapore: Department of Statistics, 2007), 144–45. (Call no. RSING 315.957 YSS) ↩

-

Department of Statistics, Yearbook of Statistics Singapore, 154–55. ↩

-

“SBF Launches Middle East Business Group To Boost Business Ties Between Singapore and the Middle East,” Singapore Business Federation, 26 March 2007, accessed 21 January 2008, https://www.sbf.org.sg/what-we-do/internationalisation. ↩

-

Peter Hopkirk, “The Rise and Fall of the Silk Road,” in Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia (London: John Murray, 1980), 14. (Call no. RUR 931 HOP) ↩

-

Hopkirk, “Rise and Fall of the Silk Road,” 29. ↩

-

Hopkirk, “Rise and Fall of the Silk Road,” 21. ↩

-

Hopkirk, “Rise and Fall of the Silk Road,” 28. ↩

-

Hopkirk, “Rise and Fall of the Silk Road,” 28. ↩

-

L. W. C. van den Berg, Le Ḥadhramout Et Les Colonies Arabes Dans L’archipel Indien (Batavia: Imprimerie du Gouvernement, 1886), 104. (Call no. RRARE 325.25309598 BER; microfilm NL7400) ↩