The Itinerario: The Key to the East

Senior Librarian Bonny Tan explores Itinerario, a book by Dutchman Jan Huygen van Linschoten that opened the secret passageway to the east for the Dutch and English.

— Jan Huygen van Linschoten

Since Vasco da Gama sailed to India in 1498, the Portuguese dominated trade between Asia and Europe for almost a century until their rivals, the Dutch and the English, found the key that unlocked the secret passageway to the East. That key was a book – the Itinerario, published in 1596 by Dutchman Jan Huygen van Linschoten. His publication remains a valued work not only for its detailed description of sea roads and conditions in Asia, but also for its beautiful engravings, early modern maps and insights into the cultures and commodities of the region.

Linschoten – Life at the Confluence

Spain

Linschoten was born in Haarlem, Netherlands, in 15631 and as a young and “idle” man, he had been “addicted to see and travel”, his passion fed through “the reading of histories and strange adventures”.2 During Linschoten’s youth, Holland and Spain were often in conflict. Despite this, trade between the Dutch and the Spanish remained vibrant and Dutchmen frequently headed to Spain for employment or business. Among them were two of Linschoten’s brothers, followed inevitably by Linschoten who journeyed out when he was 17,3 travelling to Seville in a convoy of 80 ships. There Linschoten hoped to master the mariner’s lingua franca – Spanish – so that he could travel even further.

The key moments in Linschoten’s life and the publication of his work came coincidentally at the confluence of several political events. Take, for example, his arrival in Spain. The Portuguese king, Don Henry, had died without an heir and had stated in his will that his sister’s son, Philip, the reigning King of Spain, be crowned King of Portugal in 1580, uniting once arch-rivals Spain and Portugal in a tenuous fashion.

Goa

Meanwhile, a learned Dominican monk, Don Frey Vincente de Fonseca, known to both Spanish and Portuguese royal houses, was appointed Archbishop of Goa by the king. Linschoten’s elder half-brother, Willem Tin, was already appointed clerk in the fleet heading to India. He helped enter his younger brother into the services of the archbishop. Thus Linschoten and his brother along with 38 others were recruited and sailed for Goa, India, on 8 April 1583.

Arriving at Goa in September that same year, Linschoten remained for five years until 1588, never travelling further than the surroundings of Goa. Since much of Portuguese trade to and from Asia transited at Goa, it was here that tradesmen and travellers would rendezvous after or along the way to making that mystical journey to the East. Linschoten was privy to the latest information on the East Indies, gathered through interviews with various merchants and navigators. He kept a concise diary of the people interviewed as well as his own sojourns – a tradition common among 16th-century travellers – which would later serve as a useful resource for his landmark publication.

It was as secretary and later as tax officer to the archbishop of Goa that Linschoten had access to the confidential portolans (a sailing chart or publication of sea routes and maritime navigation in textual form, derived from the Italian term portolani) and sensitive trade information meant only for high officials in the Portuguese government, giving his publication the edge over all previous guides to the East. Linschoten likely derived information from Vicente Rodrigues who was famed for his roteiro (same as portolan except that it is a Portuguese term), the first of which is found only in Linschoten’s Itinerario.4 The text also shows evidence that Linschoten referred to learned books and descriptions such as Os Lusiades by Camoes, and from Garcia de Orta on Goa, Gonzalez de Mendoza on China and Christavao da Costa on medicinal herbs.5

In fact, Linschoten’s description of sea routes was considered so accurate that Peter Floris, who journeyed to the Strait of Singapore in 1613, close to 20 years after Linschoten had published the work, said that the passageway was so well described6 “that it cannot bee mended for wee have founde all juste as hee hath described it, so that a man needeth no other judge or pilote butt him”.7 And this description comes from a man who had never been in the Malay Archipelago.

The Return

Linschoten’s love for India was such that he had wanted to remain there possibly for life, but the death of his patron, the archbishop, in 15878 led him to return to Europe in 1589. It was on this trip back that he reconnected with Gerrit van Afhuysen from Antwerp with whom he had been acquainted while in Lisbon. Travelling together, their ships anchored at Tercera to escape British ships, near the Azores; but the seasonal winds foundered the ship laden with Malaccan treasures. Afhuysen persuaded Linschoten to remain in Tercera to recover the important cargo and so Linschoten stayed on for two years, giving him the opportunity to explore the Azores and later write about it. More significantly, Afhuysen, who had been holed up in Malacca for 14 months on account of wars and tribulations in that city,9 shared with Linschoten his wealth of experience on Malacca and the surrounding islands.

It was thus only in early 1592 that Linschoten returned to Lisbon before finally returning to the Netherlands after an absence of 13 years. There he began compiling his Itinerario, selling it to Cornelis Claesz who published it only in 1596.

Linschoten’s return coincided with the liberation and independence of Holland from its Spanish masters in 1594. One of his last epic adventures was his voyage to the Arctic which he made twice, in 1594 and 1595, in search of a northeast passage to Asia. He died on 8 February 1611, having gained international fame for his publication of the Itinerario as well as community status as Enkhuizen City’s treasurer.

Linschoten’s Work – An Illustrated Guide

Linschoten’s famed publication is popularly known as the Itinerario, but this is merely the title of the first of its four books. The Itinerario, voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huyghen van Linschoten near Oost ofte Portugails Indien10 is book one, capturing Linschoten’s voyage to the East Indies, with primarily a description of the landscape and life in India plus an additional mention of the history of Malacca, the produce and people of Java and the route to China. The second book gives descriptions of the landscape from Guinea to Angola, with details of the discovery of Madagascar. It is the third book, the Reysgheshrift van de navigatein der Portugaloysers in Orienten11, which was instrumental in opening the East Indies to the Dutch and the English as it gives details of sea routes to the region, particularly to Malacca, Java, Sunda, China and Japan. It also gives a description of the West Indies as well as of Brazil. The last book gives highlights of the rents, tolls and profits taken along the journey by their sponsors.

Interwoven through Linschoten’s narrative are parallel texts on the same subject, published as italicised texts. These were interpolations by physician Bernard ten Broecke, also known by his Latin name, Paludanus. His knowledge was derived from his own travels as well as interviews with other sojourners. Native to Holland, he had taken his university degree at Padua and had then journeyed to Syria and Egypt. He took treasures from these travels back to his residence in Enkhuizen and became known for his intriguing collection of oddities. He was recognised for his intellectual prowess so much so that he was given the position of professorship at the University of Leyden in 1591, but did not accept the appointment and chose instead to remain in Enkhuizen. His reputation remains that of having coauthored this famed publication with Linschoten. His contribution to the publication, however, is not considered highly factual or close to reality.

The Illustrations

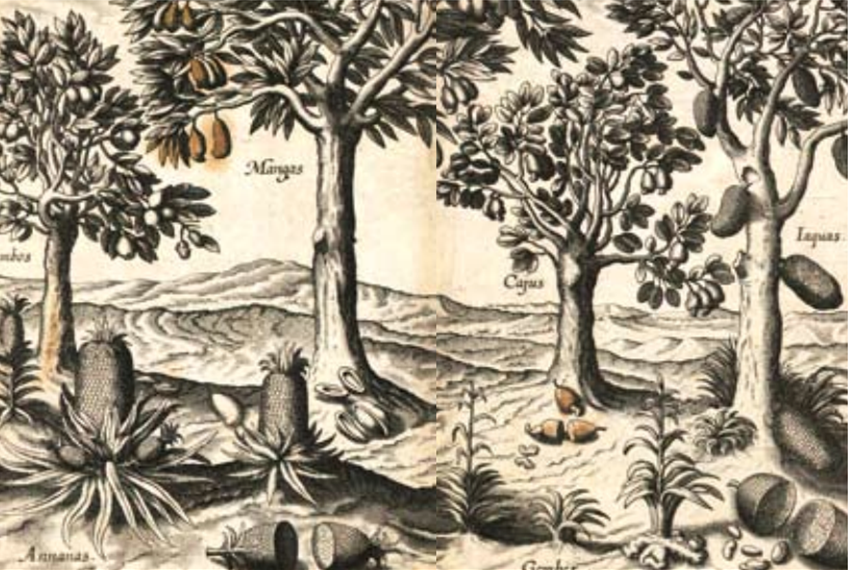

The 36 illustrations in the original Dutch publication were drawn by Linschoten himself and engraved by the sons of famed Dutch engraver Joannes van Doetecum, Joannes Jnr and Baptista. Joannes Jnr engraved at least 24 plates along with the Plancius world map and the map of the island of Mozambique. The 1598 English translation should have 21 topographical plates and 32 portraits and views.12

The views, mostly stretch across two pages, are mainly of Goa and its region, showing stylised drawings of people. Linschoten claimed that his illustrations are true to life but in the 16th-century context, this means enhanced details rather than a lifelike quality. Examples of details are the vessels utilised for travelling, such as the palanquin carried by menservants or a riverboat floating serenely, and always some aspect of fashion and lifestyle. There are also plates describing natural products with details of fruits, leaves and the whole plant.

For the first time, the people and products of the Malay Archipelago were shown in the greatest detail, scope and variety. So important were the illustrations that in 1604, the Dutch publisher Claesz republished the illustrated plates as Icones, habitus gestusque Indorum ac Lusitanorum per Indiam viventium, but this can rarely be found today.

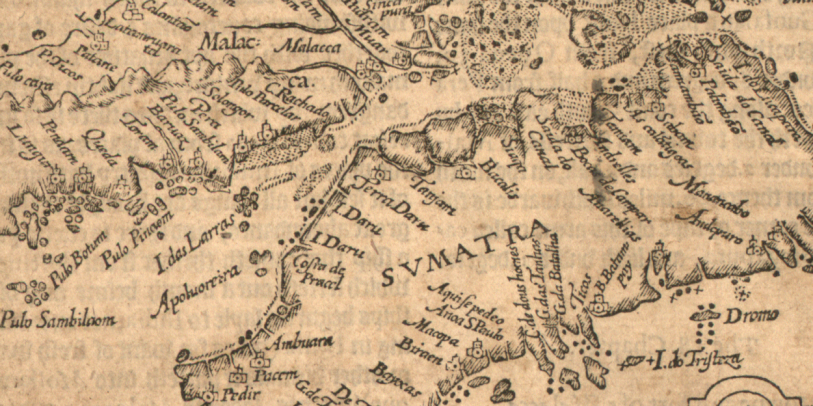

The Maps

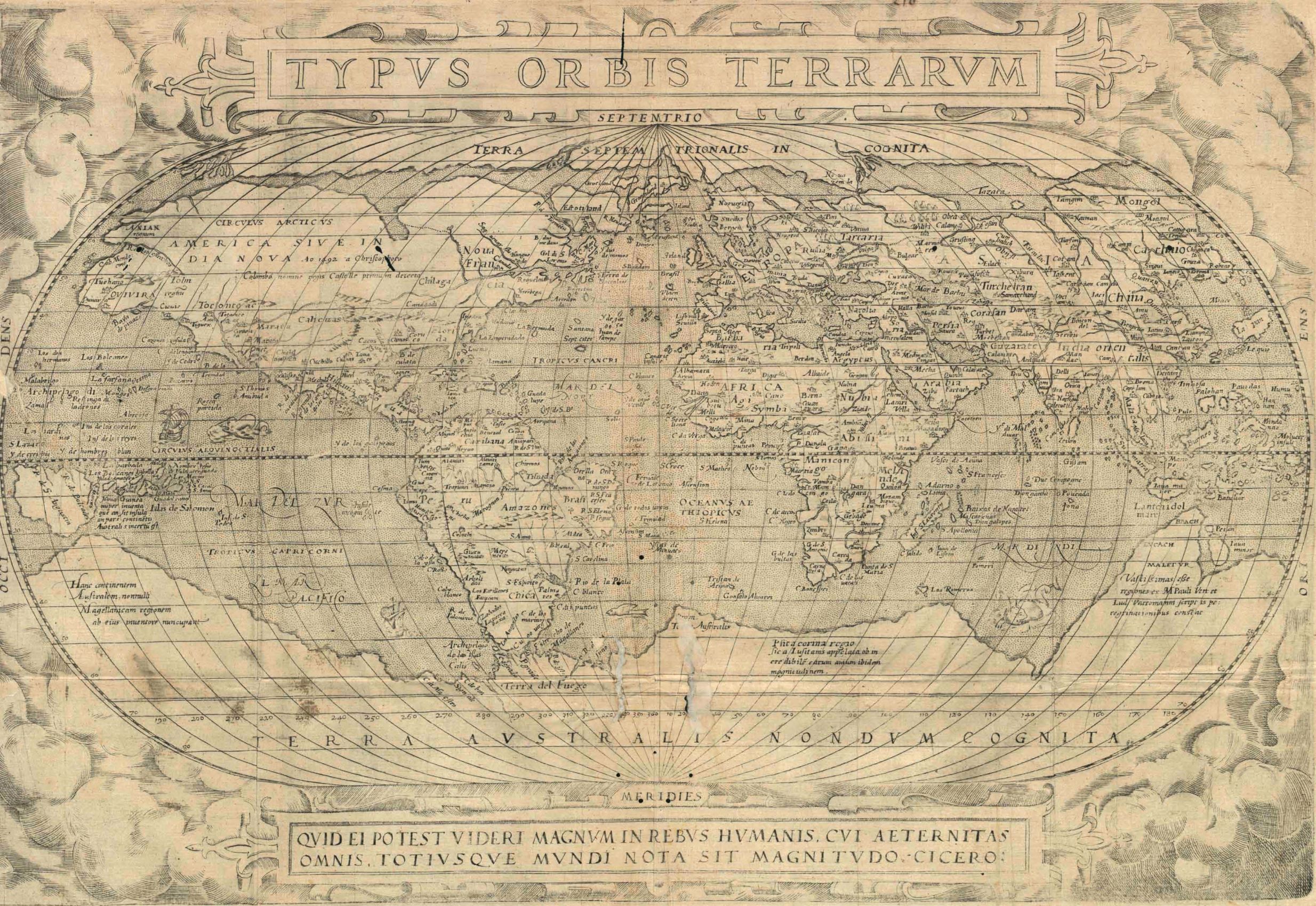

The maps are recognised for their unprecedented accuracy and detail. Many were copied from Portuguese pilots (published descriptions of navigational directions) and the works of famed cartographers such as Fernao Vaz Dourado, and most were redrawn by Dutch cartographer Petrus Plancius in the Dutch editions. Plancius’ world map shows the evolution of map-drawing from the illuminated style of the Portuguese to the finely designed Dutch copperplate prints. However, the English edition replaced Plancius’ map with the oval world map of Abraham Ortelius, the great Flemish cartographer who produced some of the earliest modern maps for the atlas Theatrum orbis terrarium (1570). Below the map is a quotation in Latin by Cicero “Quid ei potest videri magnum in rebus humanis, cui aeternitas omnis, totiusque mundi nota sit magnitude”.13 The “Typus orbis terrarum” incorporates recent navigational findings, showing a corrected west coast of South America and adding the Solomon Islands to Ortelius’ original. The Malay Peninsula and Malacca are clearly marked out in Linschoten’s English version.

The Book’s Journey

Though the Reysgheschrift was officially published in 1596, Cornelius De Houtman had taken manuscripts of the book on his voyage to the East a year earlier.14 The Dutch navigator De Houtman and his brother were previously arrested by the Portuguese for attempting to steal their maps of trade routes to the East, but the newly formed Dutch Company of the Far East15 paid for their release and, with Linschoten’s publication in hand, they left with a convoy of four ships for the Moluccas and the treasures of the Spice Islands. Following the directions of Linschoten, De Houtman proceeded via the Sunda Strait rather than the Malacca Strait.16 By 1596, trade agreements were signed with Java, Sumatra and Bali and the dominance of the Dutch over the Malay Archipelago was sealed. The Dutch would remain there for more than three centuries.

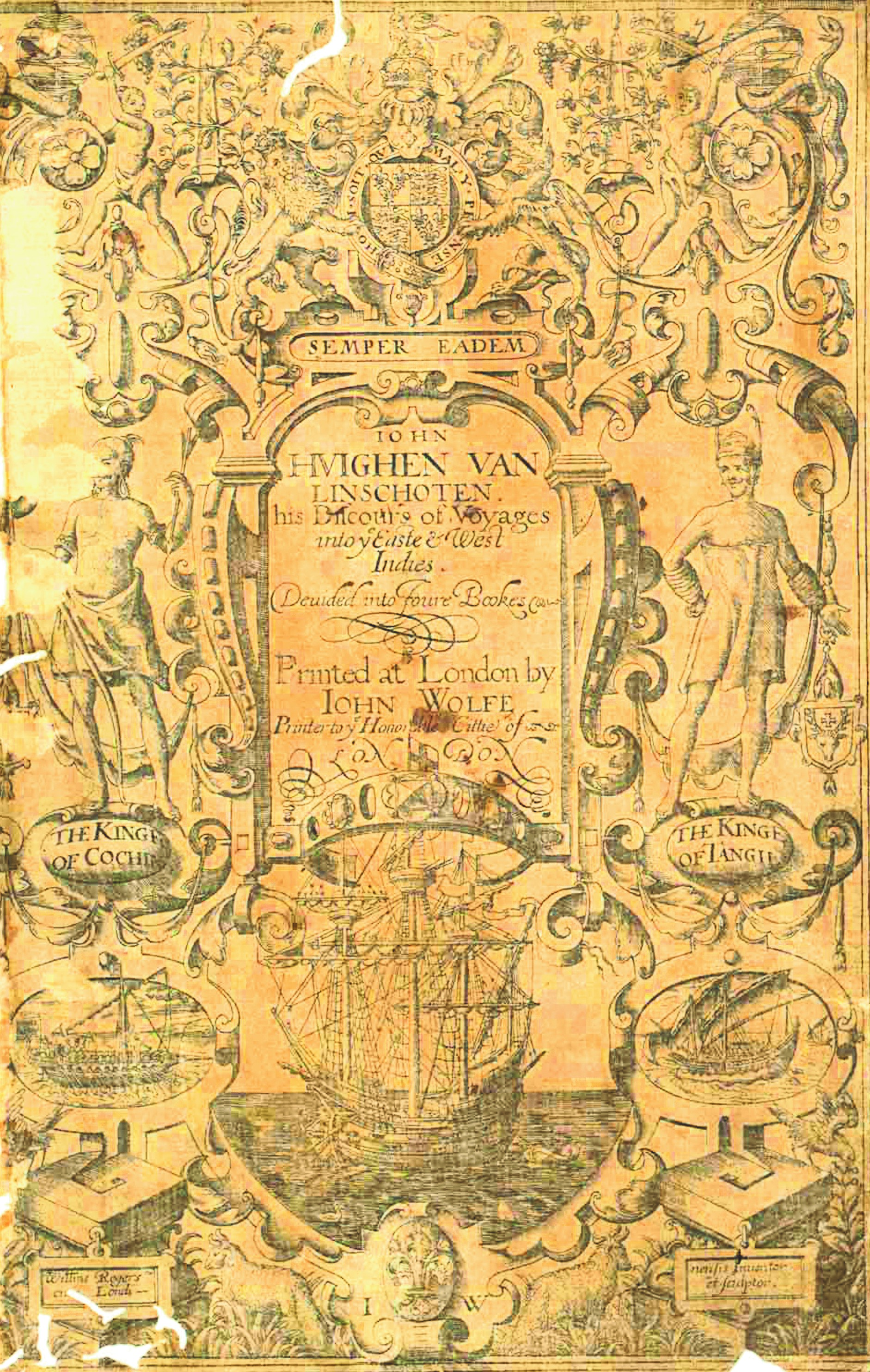

The English edition was published in 1598 entitled Iohn Huighen van Linschoten his Discours of Voyages into ye Easte & West Indies. It was Linschoten who sought to have the English version published and Iohn Wolfe rose to the task, encouraged by another travel buff, Richard Hakluyt. Wolfe dedicated the English publication to Julius Caesar, Judge of the British High Court of Admiralty. It was Hakluyt who recommended this title as an indispensable pilot for shipmen of the newly formed East India Company.

A German translation was published the same year as the English, and by 1599 there were two Latin versions, namely one in Frankfurt and another in Amsterdam. The French translation was first published in 1610 and again in 1619 and 1638. Subsequent Dutch editions were released in 1604, 1614, 1623 and 1644. Although the Itinerario was republished in English, namely by the Hakluyt Society in 1885, the Reysghescrift remained out of print despite its popularity in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Inside Linschoten’s Work – Impressions of Early Malaya

Malacca’s People

Portuguese dominance over the trade routes to the East in the 16th century was established by Afonso de Albuquerque through strategic military conquests. He anchored Portuguese power in Goa in 1510 before traversing to Malacca, overcoming it by August 1511. He died not long after in 1515, spending his last days in Goa. By the time Linschoten was based in Goa, Portugal’s principal traffic was to Malacca, China and Japan.17 In his book Linschoten notes that once a year, a ship left Portugal, a month ahead of any other ship, barely landing in India to add new stock of water and food, before heading to Malacca. There it was laden with merchandise and spices, twice as much as any ship from India, heading back with its riches to Portugal.

In Chapter 18 of the Itinerario, Linschoten introduces the town and fort of Malacca in greater detail. Traders were using Malacca as a stopover for water and food, while waiting for the monsoon winds to change and take them to their next destination. However, few Portuguese chose to remain in the town because of the “evil air” there as “there is not one that cometh thether, and stayeth any time, but is sure to be sicke, so that it costeth him either hyde or hayre, before he departeth from thence”.18

The chapter also provides keen insights into the residents of Malacca in the 16th century. Of the Malays, Linschoten describes them as “the most courteous and seemelie speech of all the Orient, and all the Malaiens, as well men as women are very amorous, perswading themselves that their like is not to be found throughout the whole world”.19 He refers to their “ballats, poetries, amorous songs” as evidence of their beauty and culture.

In the Icones, Linschoten illustrated and described the Malays in Malacca as follows: “its inhabitants have striven for specific qualities and created a language different from that of the other peoples. That language, called Malay, grew in prestige and influence with the city itself and is spoken by almost all Indians, like French among us, and without the assistance of that language a person is hardly of any account. The people themselves are educated, friendly, and civilised, and are more affable than any other people of the East. The women have just as large an innate interest for music and rhetoric as the men and a confidence of achieving more in those fields than other peoples. They all equally value the combination of music and song. So has nature endowed them with the beauty of talent”.20

Malacca’s Fruits

Throughout the first book, descriptions of Malaccan fruits, their plant, taste and uses, are given in lucid detail. In Chapter 51, the mangos of the East as found in India, Myanmar (Pegu) and Malacca are described. The locals considered it a heaty fruit as it was believed to cause “Carbuncles, hotte burning Feavers, and swellings”. Linschoten notes how it “is eaten with wines… [and] preserved… either in Sugar, Vinegar, Oyle or Salt, like Olives in Spain, and being a little opened with a Knife, they are stuffed with green Ginger, headed Garlic, Mustard or such like, they are sometimes eaten only with Salt, and sometimes sodden with Rice, as we doe Olives, and being thus conserved and sodden, are brought to sell in the market”.21 Some 500 years later, the fruit seems to still be consumed and preserved in similar ways in Southeast Asia.22

It is the Jambos (jambu or rose apple) that Linschoten sings praise of for its “pleasant taste, smell, and medicinable virtue”.23 It was believed to have been taken to India via Malacca. He describes two types of jambu fruits, “one a browne red… most part without stones, and more savory then the other which is palered, or a pale purple colour, with a lively smell of Roses”.24 The fruit is usually eaten as an appetiser or to quench one’s thirst.

The king of fruits is not forgotten and there is a full chapter on the Duryoen25 or durian. Considered peculiar to Malacca, the fruit was even at that time thought to be incomparable in “taste or goodness” to any other fruit – “and yet when it is first opened, it smelleth like rotten onions, but in the taste the sweetnes and daintinesse thereof is tried”.26 He also notes the strange effect that the betel leaf has on the durian. He describes how a shipload or even a shopful of durians can turn bad by merely being in contact with a few leaves of the betel. The betel is so able to counteract the durian’s heatiness that inflammation of the (mouth) caused by overeating durians can easily be cured by eating a few leaves of betel. This was an important fact since “men can never be satisfied with them [the durians]”.27

Singapore

Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, director of the Raffles Museum between 1957 and 1963, was well known for his encyclopedic knowledge of Malaya. One of his many articles published in the respectable Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, entitled “Singapore: Notes on the Old Strait (1580–1850)” (1956),28 noted how the “Straight of Sincapura” (Strait of Singapore) was already described in detail in Linschoten’s Resygheschrift.29 Gibson-Hill believed the Portuguese had known of the strait since their earliest occupation of Malacca. Gibson-Hill suggests the value of Linschoten’s description is in the fact that “the routes described are not compromises between the pilot’s preferences and the run of wind and weather. They represent, in fact, the considered opinions of experienced men over the 15 to 20 or more years before Linschoten left Goa”.30

In his article, Gibson-Hill reprints the Linschoten’s description of the passageway in full, giving contemporary names to Linschoten’s 16th-century landmarks. In part, Gibson-Hill’s analysis of present day place names was based on an earlier reprint of the same passage of the Resygheschrift which was published in the Singapore Free Press (2 November 1848) with annotations thought to be those of the great Malayan philologist J.R. Logan.31 So detailed is Gibson-Hill’s research that he notes the error in Linschoten’s page numbering for the start of Chapter 20.32 Gibson-Hill’s understanding of the route also goes beyond book knowledge – he had taken a launch in 1951 to personally follow Linschoten’s directions.

The National Library’s Copy

The 1598 English edition of the Itinerario found in the National Library holdings came through Gibson-Hill when his personal library was donated in 1965 according to the intentions of his close friend Loke Wan Tho, famed as owner of the Cathay cinemas and for his passionate interest in Malayan natural heritage. Among his many social positions, he had been the chairman of the National Library Board in which position he had considered purchasing Gibson-Hill’s private book collection for the library soon after the latter’s sudden death. The copy in the National Library has lost its original cover and its title page is damaged, although it still retains its fine illustrative design and clearly shows it is the translation by John Wolff and printed in London. Interestingly, Gibson-Hill had also obtained the 1885 reprint published by the Hakluyt Society after noting that the Raffles Library collection which he so often consulted had no copy of this title. Both copies were likely used extensively for Gibson-Hill’s study on the Strait of Singapore and related research on local waterways. Today, the 1598 version of Linschoten’s book can be fully accessed from the Digital Library33 as well as through microfilm at Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library. The 1885 version is also accessible through microfilm.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

C.A. Gibson-Hill, Singapore: Notes on the History of the Old Strait, 1580–1850 ([Singapore]: Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society. 1954). (Call no. RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS; microfilm NL0029; NL0078)

C.A. Gibson-Hill, Singapore: Old Strait & New Harbour, 1300–1870 (Singapore: General Post Office, 1956). (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 BOG; microfilm NL10999)

Ernst Van Den Boogaart, Civil and Corrupt Asia: Image and Text in the Itinerario and the Icones of Jan Huygen Van Linschoten (London: University of Chicago Press, 2003). (Call no. R 915.043 BOO)

J. Potter, “The World Through Travellers’ Eyes,” Geographical 74, no. 4 (2002): 12.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten, The Voyage of John Huyghen Van Linschoten to the East Indies. From the Old English Translation of 1598. The First Book, Containing His Description of the East. Ed., the First Volume by the Late Arthur Coke Burnell, the Second Volume by P. A. Tiele (London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1885). (Call no. RRARE 910.8 HAK; microfilm NL 24339, NL24340)

John Hvighen van Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, His Discourse of Voyages Unto Y Easte & West Indies: Deuided Into Foure Bookes, trans. W. Phillip (London: Iohn Wolfe, 1598) (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 910.8 LIN; microfilm NL8024)

Jurrien van Goor and Foskelien van Goor, Prelude to Colonialism: The Dutch in Asia (Uitgeverij Verloren, 2004)

“Linschoten’s Itinerario,” King’s College London, University of London.

Richard Pflederer, “Dutch Maps and English Ships in the Eastern Seas,” History Today 44, no. 1 (January 1994): 35–41.

Thomas Suarez, Early Mapping of Southeast Asia (Hong Kong: Periplus Editions, 1999). (Call no. RSING 912.59 SUA)

W.H. Moreland, ed., Peter Floris: His Voyage to the East Indies in the Globe 1611–1615 (London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1934). (Call no. RCLOS 910.8 HAK)

NOTES

-

His family is believed to have originated from a village in Utrecht named Linschoten. His parents Huych Joosten and Maertgen Hendrics lived in Schoonhoven which was a short distance away from Linschoten. (From the introduction by P.A. Tiele in Linschoten, Voyage of John Huyghen Van Linschoten, xxiii.) ↩

-

John Hvighen van Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, His Discourse of Voyages Unto Y Easte & West Indies: Deuided Into Foure Bookes, trans. W. Phillip (London: Iohn Wolfe, 1598), 1. (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 910.8 LIN; microfilm NL8024) ↩

-

A number of sources indicate the year as 1579. ↩

-

Jurrien van Goor and Foskelien van Goor, Prelude to Colonialism: The Dutch in Asia (Uitgeverij Verloren, 2004), 51–52. ↩

-

Goor and Goor, 52. ↩

-

Found in the original publication in Chapter 20 (Linschoten, _John Hvighen Van Linschoten ↩

-

W.H. Moreland, ed., Peter Floris: His Voyage to the East Indies in the Globe 1611–1615 (London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1934) 104 (Call no. RCLOS 910.8 HAK) in C. A. Gibson-Hill, Singapore: Notes on the History of the Old Strait, 1580–1850 ([Singapore]: Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society. 1954), 165, 167. (Call no. RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS; microfilm NL0029; NL0078) ↩

-

The archbishop died while journeying to Lisbon in 1587, and Jan received the news of his death only in September 1588 (Linschoten, Voyage of John Huyghen Van Linschoten, xxvii). ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 172. ↩

-

Often translated as “Seavoyage of Jan Huygen van Linschoten to the East or Portuguese Indies”. In the Dutch version it is Book I. ↩

-

Translated as “Travel accounts of Portuguese navigation in the Orient” also sometimes known as “a seaman’s guidebook to India and Far Eastern navigation” or “Pilot’s guide”. It was originally Book II in the 1595 Dutch imprint but in the English version, it is Book III. ↩

-

However, the copy at the library’s holdings only has 16 views and eight maps or topographical drawings. ↩

-

“What among human affairs can seem great to him who knows eternity and the whole of the universe?” ↩

-

Thus the Reysgheschrift was released a year prior to Book I – the Itinerario. ↩

-

It had just been established in 1594. ↩

-

Thomas Suarez, Early Mapping of Southeast Asia (Hong Kong: Periplus Editions, 1999), 180. (Call no. RSING 912.59 SUA) ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 31. ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 31. ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 31. ↩

-

Ernst Van Den Boogaart, Civil and Corrupt Asia: Image and Text in the Itinerario and the Icones of Jan Huygen Van Linschoten (London: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 54. (Call no. R 915.043 BOO) ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 93. ↩

-

For example, mango chutney recipes include garlic, vinegar, brown sugar and salt and a form of Portuguese mango chutney is still being made in Malacca using similar ingredients. ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 95. ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 95. ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, Chapter 57. ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 102. ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, 103. ↩

-

So detailed is Gibson-Hill’s research that he notes the error in page number for the start of Chapter 20 of Linschoten’s 1598 Itinerario (C.A. Gibson-Hill, Singapore: Old Strait & New Harbour, 1300–1870 (Singapore: General Post Office, 1956), introduction, 11. (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 BOG; microfilm NL10999)). ↩

-

Linschoten, John Hvighen Van Linschoten, chapter 20 from page 336 of Book III. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, Notes on the History of the Old Strait, 165. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill actually questions W.D. Barnes’ analysis based on the French edition of Linschoten which he published in JSBRAS in 1911 for going about it in such a convoluted fashion when the English version had already been reprinted in the Singapore Free Press. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, Notes on the History of the Old Strait, introduction, 11. ↩