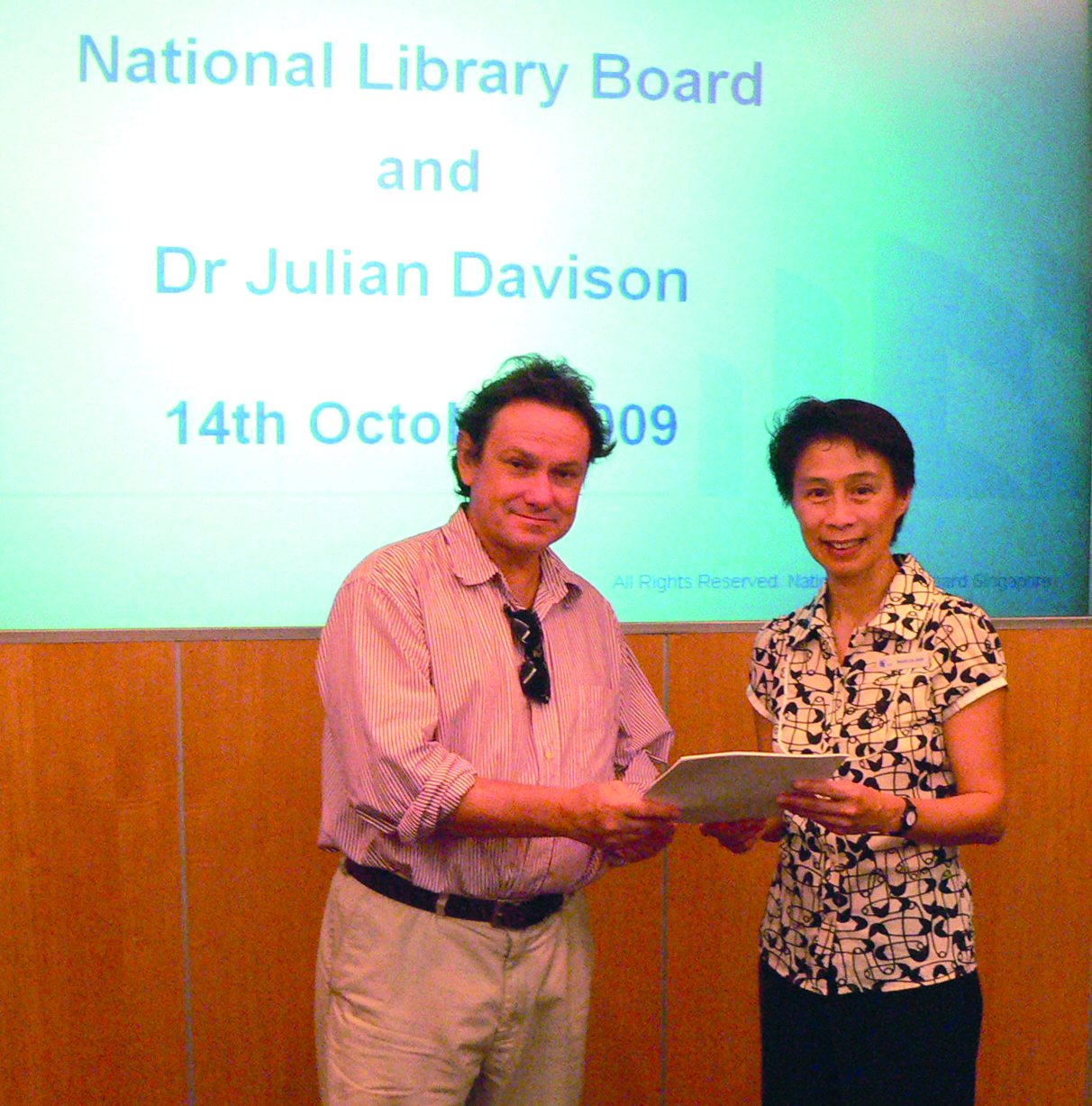

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow: Dr Julian Davison

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Dr Julian Davison shares the story of his life and family.

Although I am a British citizen, my family has been connected with Singapore for four generations. My great-grandfather, a Welshman by the name of William Morris, was here in the 1880s. He was a sea captain who owned his own ship – whether it was a sailing vessel or a coastal steamer, I know not – and plied the waters of the South China Sea, ferrying cargoes back and forth between Singapore and Bangkok. This was in the time of Joseph Conrad, author of Lord Jim, Almayer’s Folly, Outcast of the Islands and many other stories set in this part of the world around the turn of the last century. Back then, Conrad was first officer aboard the Vidar, a schooner-rigged steamship owned by the Singaporean Al Joofrie family and I often wonder if the two men met, perhaps at Emmerson’s Tiffin Rooms down by Cavenagh Bridge, which in those days was a place of rendezvous for ship’s officers and other seafaring types.

My grandmother was born in Singapore in the early 1890s and she liked to tell the story of how on one of her father’s voyages to some remote part of the Malay Archipelago – he would sometimes take his family along – a “cannibal king” offered to purchase her sister and her – two dazzling blue-eyed little Welsh girls with curly blonde locks – for a very considerable amount of cowrie shells, the medium of exchange then. I also remember my grandmother telling me that when she was little she had a friend who lived in a bungalow far from town and when she sometimes went there to stay with the family at weekends they could hear tigers roaring at night.

My grandmother was married in the early years of World War I to another Welshman by the name of Percy Davison from Colwyn Bay. Davison was an accountant, later director, with United Engineers, and the wedding took place in the Presbyterian Church at the end of Orchard Road near the National Museum which is also where my father, Robert, was christened in 1920. They lived in a rambling Anglo-Malay-style bungalow on Mount Rosie, which I remember visiting as a child but which is sadly long since gone. When he was eight years old, my father was packed off to boarding school in England as was the custom for expatriate families in those days. At the age of 11, however, he was brought back to Singapore for a year so that he could be reacquainted with his father whom he hadn’t seen in the interim; and during that time he attended Raffles Institution. When the year was up, my father went back to England to resume his studies there and I’m not sure that he saw his father again until he left school.

My father wanted to be an artist – I have a very lovely seascape in oil painted by him when he was 17 – and he evidently had talent. But my grandfather said: “Forget it, I’m not sending you to art school. Artists never make any money; you’ll be poor for all your life.” So my father settled for becoming an architect instead. He had no sooner started at the prestigious Architectural Association (AA) in London when along came World War II. My father volunteered for the Royal Navy and served in the Mediterranean, rising to the rank of lieutenant by the end of the conflict. Returning to his studies after the war, my father completed his diploma at the AA and for a while worked in the UK.

It was, however, always his ambition to return to Singapore and, in the early 1950s, he was happy to accept the offer of a job as an architect with the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT), forerunner of today’s Housing Development Board (HDB). His father was dead by this time and other family members who had lived in Singapore before the war – there were aunts and uncles and cousins – had either retired or died (one of my great uncles was a high court judge who was lost at sea when his ship was torpedoed in the Indian Ocean), so my father was on his own.

After a couple of years with the SIT, my father decided that he would like to go into private practice, which led him to return to England where he joined the architectural practice Raglan Squire & Partners in London. This is when he married my mother whom he had met during the war at the naval base in Haifa, in what was then Palestine. They were married in 1955 and it so happened that at the time, my father’s boss, Raglan Squire, or “Rag” as he was more popularly known, was engaged in a major project in Burma, today’s Myanmar, and was looking to set up a regional office in Southeast Asia. This was how my father, together with two other colleagues from the London office, came back to Singapore in 1956 and set up a local branch of Raglan Squire & Partners, better known today as RSP. The firm is currently completing the huge ION Orchard complex at the junction of Orchard and Paterson roads.

The year 1956 was also the year that I was born, in London, which is how I happen to be a British citizen (my father was, of course, a red passport holder by virtue of having been born here). As soon as I was old enough to travel (six weeks) my mother and I boarded the SS Canton and set sail for Singapore to join my father who had gone on ahead to set up the new office (coincidently the Canton was the same ship which brought the young (Minister Mentor) Lee Kuan Yew back from his studies in England, albeit a couple of years earlier).

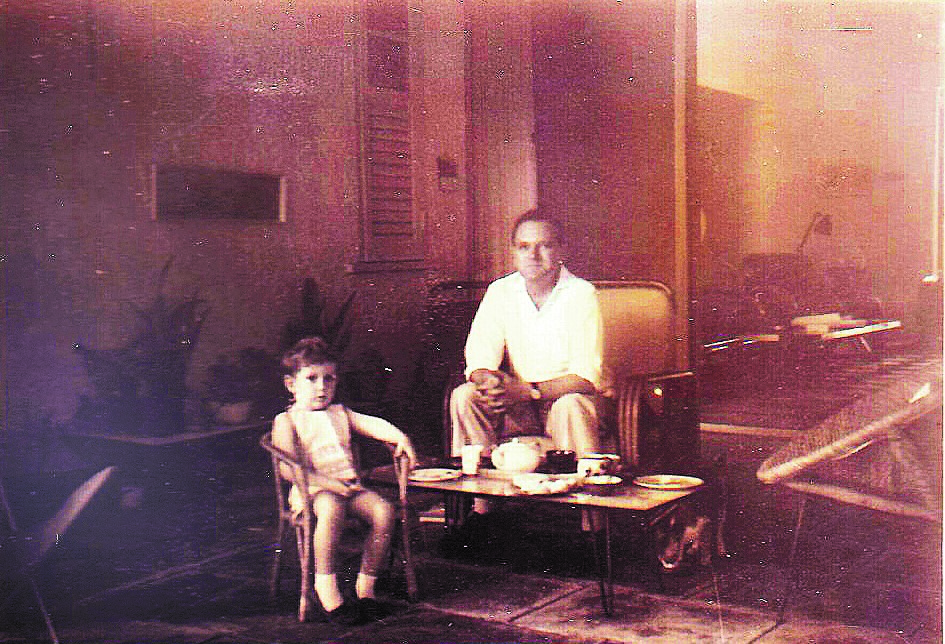

For the first six years of my life, I lived in Singapore in a modest bungalow off Braddell Road. This was considered a very ulu (countryside) location in those days – we were surrounded by kampongs and pig farms and market gardens – but to me it was paradise – a large garden to run around in with birds and bugs, and, on the other side of the bamboo hedge, kampong boys to play with.

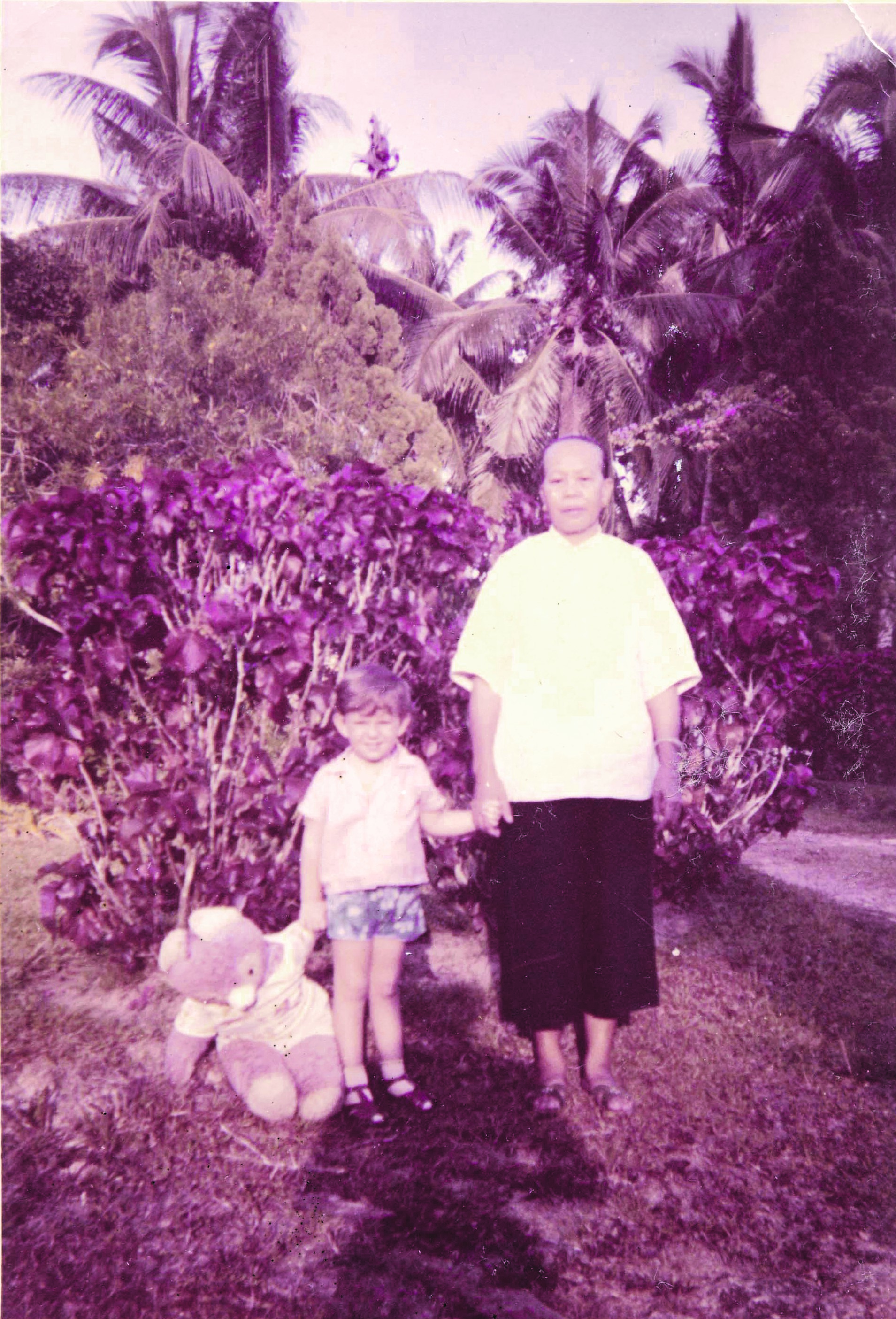

In those days every relatively well-to-do family employed an amah (domestic help) who not only did the housework and cooking but also looked after the children. We were very fortunate to have working for us one of those traditional “black and white” amahs from Canton (Guangzhou), Ah Jong by name, who ended up staying with our family for almost 20 years. As a boy I used to love hearing the stories of her own childhood back in China, the life of a young peasant girl living in the countryside interspersed with moments of high drama – more than once she had to hide in the attic when bandits came to the door looking for young girls to kidnap to sell into prostitution in Nanyang. My only regret is that I didn’t learn to speak in Cantonese with Ah Jong – at three years old I’m sure that even the most resistant ang moh ear would eventually master the tonal cadences of the Chinese dialect. Instead we conversed in pasar Malay with a few Peranakan phrases and the occasional word in English thrown in for good measure.

In 1962, my father decided it was time to expand the office to Kuala Lumpur, and this is where he ended up working for the next 17 years until his eventual retirement in 1979. For my part, I initially went to school here in Singapore – first at St Paul’s on Upper Serangoon Road, followed by the Tanglin School – and then later in Kuala Lumpur. When I was nine years old, however, I was sent off to boarding school in England, like my father before me. This was quite a shock to the system, not only because the climate was so cold but also because England to me in those days was very much a foreign country – “home” for me was in every sense of the word, Malaysia.

School was followed by university in the north of England, Durham (colder still), where I studied anthropology, naturally specialising in the ethnography of Southeast Asia. By the time I graduated, my parents were coming up for retirement and were planning to move to Spain where my father had built for himself a house on top of a mountain. With no family home in the Far East anymore, I went to London and this was where I lived for the next 10 years, during which time I completed a PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies. The focus of my study was traditional headhunting practices and rituals among the Iban of Sarawak and this, of course, brought me back to Southeast Asia, which was the whole idea in the first place!

And it also brought me back to Singapore. At first, I was just passing through or stopping over for a bit of rest and recreation after a couple of months in the jungle living in an Iban longhouse. Later, I got a job here as editor with a French publishing house based in Singapore. After three years there, I decided that I would try my hand at writing myself, rather than simply tidying up someone else’s manuscript for publication, and this is how I come to be where I am today – a freelance writer living in Singapore, specialising in local history with a particular interest in local architecture.

My most recently published work is a coffee-table book on black-and-white bungalows from the colonial era, while my next book, which should be on the bookshop shelves some time early next year, is a study of the Singapore shophouse from its origins in China to the present day. I have also published a couple of volumes of collected stories and reminiscences relating to my childhood – kenang-kenangan, as one would say in Malay – entitled One For the Road and An Eastern Port, respectively; both these volumes, as well as the Black and White: The Singapore House from 1898–1941, can be found on the shelves of the National Library.

I have also had the good fortune to have been invited to research and host a series of a local history programmes for Singapore television; Site and Sound was the title and there were three series in all, running to 36 episodes. They were great fun to do, giving me a chance to work with very talented people – the director, cameraman and all the rest of the crew – and enabling me to visit all sorts of unusual places connected with Singapore’s past and meet a wide range of very interesting people. It was definitely one of the best jobs I ever had!

Now I am looking forward very much to my six months at the National Library as a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow when I shall be exploring what Singapore was like in the 1920s and 1930s. My starting point is that this is when Singapore first became “modern” in ways that we can understand and appreciate today – early skyscrapers and mass rapid transport systems, apartment living and contemporary design, movies, radio broadcasting and a popular culture of magazines and music, fashionable dressing and jazz-age celebrity lifestyles. Watch this space!

The Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship invites scholars, practitioners and librarians to undertake collection-related research and publish on the National Library of Singapore's donor and prized collections. The fellowship aims to position the National Library Board as the first stop for Asian collection services. It is open to both local and foreign applicants, who should preferably have an established record of achievement in their chosen field of research and the potential to excel further.

For information on the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship, please contact the Administrator at:

Email: LKCRF@nlb.gov.sg

Tel: 6332 3348

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library