In Touch with My Routes: Becoming a Tourist in Singapore

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Desmond Wee ponders the Singaporean identity while being a tourist in Singapore.

— Pamelia Lee (2004, p. 99)

It struck me when the Merlion was struck, more by the discourses around it than the stroke of lightning that bore a hole in its skull. Forty-five years after its creation, I wonder about the Merlion as an emblem for the Singapore Tourism Board (STB), how Singaporean Fraser Brunner felt when he conceptualised the animal and if that mattered at all. According to the Report of the Tourism Task Force 1984 (in Schoppert, 2005, p. 25), “what Singapore suffers from is an identity problem as there is no landmark or monument which a tourist can easily associate Singapore with”. In a paper for a course “Questioning Evolution and Progress” at the National University of Singapore, Devan (2006, p. 4) related the issue, rather than being about “how tourists identify Singaporeans” it was about the Singaporean “struggle for an identity”.

However, the complexities of identity acquisition cannot elude how tourists identify Singaporeans. As described by Lanfant, Allcock & Bruner (1995, p. ix), it is tourism which “compels local societies to become aware and to question the identities they offer to foreigners as well as the prior images that are imposed upon them”. Representations in this sense are not only constituted by embodied practices, but they also constitute the ways in which identities are performed. By the same token, Singaporeans identify tourists as much as tourists identify Singaporeans, and in asking how Singaporeans identify themselves in the fostering of identity, I also ask if it is possible for Singaporeans to identify themselves as tourists. Who is the Singaporean under the Merlion?

Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew once remarked that economic progress must not undermine the “heartware of Singapore” referring to “our love for the country, our rootedness and our sense of community and nationhood” (The Straits Times, 20 October 1997). The cultivation of identity, as a need and means of survival, has evolved into a “substantial injection of selfdefinition and national pride” (Chua & Kuo, 1990, p. 6). However, given the birth of active citizenry, contestations across and in between routes pertaining to the definition of self come to the fore. Kellner (1992) has suggested the emergence of identity as a “freely chosen game” in a “theatrical presentation of the self”. In this sense, our rootedness is also our “routedness”, a play in which identities are constituted within and not outside representation, and “relate to the invention of tradition as much as to tradition itself” (Hall, 1996, p. 4). Instead of the “so-called return to roots”, Hall (1996, p. 4) advocates a “coming-to-terms-with our ‘routes’” with which we can relate to cultural identities as fluid and emergent rather than being static. In the same way, Crouch, Aronsson and Wahlström (2001) maintain that the consideration of place and its represented culture “through encounter as ‘routes’ suggests a much less stable and fixed experienced geography”. This framing of text in terms of a becoming of identity repositions the performance of self as “the changing same” (Gilroy, 1994) and discusses the myriad ways in which knowledge and performances based on their representations are being (re)produced.

That ubiquitous “where are you from?” question which constantly follows tourists becomes variegated within the space of modernity evidenced through a measure of uncertainty as fluid productions of meanings manifest. With emergent hybridities evidenced in the blurring of traditional dichotomies such as subject-object, production-consumption and tourist-local, it becomes increasingly difficult to ascertain a place called “home” and separate images and experiences that shape tourism from the every day. McCabe (2002, p. 63) reiterates that “tourism is now so pervasive in postmodern society that, rather than conceiving tourism as a ‘departure’ from the routines and practices of everyday life, tourism has become an established part of everyday life culture and consumption”. The “touristification of everyday life” (Lengkeek, 2002) is evident in a “spectacular society bombarded by signs and mediatised spaces [where] tourism is increasingly part of everyday worlds” (Edensor, 2001). While “everyday sites of activity are redesigned in ‘tourist’ mode’” (Sheller and Urry, 2004, p. 5), I ask how we deal with “becoming a tourist” and who becomes the tourist. By contemplating the tourist, tourist place and tourist practice and their concomitant relationships, what are the kinds of dynamics that (re)produce these spaces and how do these relate to the acquisition of identity?

In an indispensable relationship between tourism and identity in which one informs the other, my research in Singapore induces the questioning of identity in terms of the spatial and embodied practices of tourism and the (re)production of representations and discourses which are performed every day. Identities rather than being rooted by place, are re-emerging with new meanings and attributions. What is home? Who is a tourist? Can I be tourist at home? When does that liminal transition happen and when it does, how do I perform tourism? This paper considers how tourist practice is assimilated in the context of the every day through “local” consumption, its translation into tourist identities and vice versa. In contextualising the city and juxtaposing my three-pronged reflexivities as researcher, tourist and local in Singapore, I explore how Singaporeans perform tourism en route home through institutional attempts to “rediscover” and “love” the city and the local reiteration of place and identity.

Representing Tourist

After a visit to the Singapore Visitors Centre, I was armed with things to do around Sıngapore. From the “topless” Hippo Bus tours which gave me an overview of the city, I ventured into the four ethnic quarters in the name of cultural tourism. I visited Chinatown, Little India, Kampong Glam and the colonial district; I took a bumboat ride along the Singapore River to marvel at the waterfall spouting out of the Merlion’s mouth. Since I was travelling alone and could not take photographs of myself and my experience on the boat, I sought postcards like any tourist would. I also consulted the National Library educational e-resource, OnAsia which consisted of “high-quality copyrighted images created by some of Asia’s finest photojournalists and photographers”, featuring “photographic essays, stock photographs and conceptual images that represent a unique visual description of Asia, offering online access to a comprehensive collection of historical, political, social, and cultural images”. By using two search criteria: “tourism” and “tourist”, I extracted and sought an analysis of visual imagery and descriptions which determined place in a tourist setting.

Upon viewing both images and attached descriptions in Figures 1 and 2, I realised that through an other perception, I became by default, a tourist the moment I was in the boat. My choice to engage in a tourist activity in a designated tourist area afforded a tourist practice that made anyone who sat in the boat a tourist. In Figure 3 and within the same area, Duggleby likewise captured yet another tourist, this time taking a photograph. Without a prior knowledge, one would become a tourist while indulging in tourist practice within a tourist place. But at which point did I become a tourist? How do we determine the confines of what constitutes a tourist place and the reciprocity of practice in place?

Still within sight of the Sıngapore River, Figure 4 demonstrates what one might “mistake” for passers-by or pedestrians, tourists walking on the waterfront. In fact, I was a tourist even before I arrived at the ticketing booth. The sense of place and what constitutes identifiable tourist space remain arbitrary depending on the kinds of performances delineated by embodied practice.

In Figure 5, there is a total reversal in which the Caucasian man carrying a camera in a place of worship frequented by tourists, is suddenly acknowledged as a Buddhist devotee, rather than as a tourist. Perhaps the man was, or at least considered himself to be, a devotee or a local, rather than a tourist. If not, at least the photographer thought so. The issue is an epistemological one, delving into the knowledge produced and reproduced in order to sustain performance, perhaps also incorporating other roles such as tourist Buddhist devotee, expatriate Buddhist devotee or local Buddhist devotee.

Both tourist practice and the emphasis on place invite interpretations which seem to disclose the “increasing difficulty of drawing boundaries between the tourist and people who are not tourists” (Clifford, 1997) in which distinguishing a tourist becomes “more difficult in circumstances of more complex tourist practices” (Crouch, Aronsson and Wahlström, 2001). The performance of place seems to elicit emerging definitions of tourist and how tourism is performed. In other words, all the photographers of the images reproduced above were also tourists doing tourism as they were indulging in taking photographs of tourists and tourism. It is within this context that creative spaces are developed in terms of social practice, in which the place determines the performance of tourists.

Identifying the Tourist

One definition of the tourist in cultural tourism is a “temporarily leisured person who voluntarily visits a place away from home for the purpose of experiencing a change” (Smith, 1977). Since then there have been definitions in terms of typology (Cohen, 1979), performance (Edensor, 2001) and even ambiguities (McCabe, 2002) whose author advocates an investigation into the forms of touristic experience rather than the concept of the tourist as a stable category within tourism discourses. In an email correspondence with a representative of the Singapore Tourism Board (STB), in my capacity as a tourism researcher, I asked how the STB would define the tourist, and received this:

“The STB looks at more than tourists. We welcome visitors (non-residents) who visit Singapore for all kinds of purposes, be it Leisure, Business, Healthcare or Education.”

How would residents fit into this broad, welcoming definition? The current Beyond Words concept, which is part of the greater Uniquely Singapore campaign, “moves beyond promoting the destination through product attributes and strives to bring out the depth of the Singapore experience” (STB, 18 July 2006), illustrated in the article entitled “‘Beyond Words’, The Next Phase Of Uniquely Singapore Brand Campaign, Breaks New Ground”.

On-Ground Creative Approach

The new creative experience for the on-ground component of the new campaign Beyond Words strikes a deep chord with locals (and local families, businesses, retailers and hospitality agents) as well as generates multiple layers of local and international (ASEAN) publicity. It is designed to promote direct interaction between locals and tourists to enhance the “personal experience” element that is beyond words. Refreshing and vibrant bus wraps, taxi wraps, personalised bus hangers with information on various attractions, mobile display units, banners and standees – all combine to make the brand personable and accessible to both locals and visitors in Singapore.

The depiction of various modes of visual paraphernalia with the aim of personalising experience is perhaps less convincing and creative than the point that tourists and, especially, locals are targeted as part of this direct interaction. Indeed the STB welcomes more than “non-residents”, but how would residents or locals consume this new creative experience and would this consumption be any different from that by tourists?

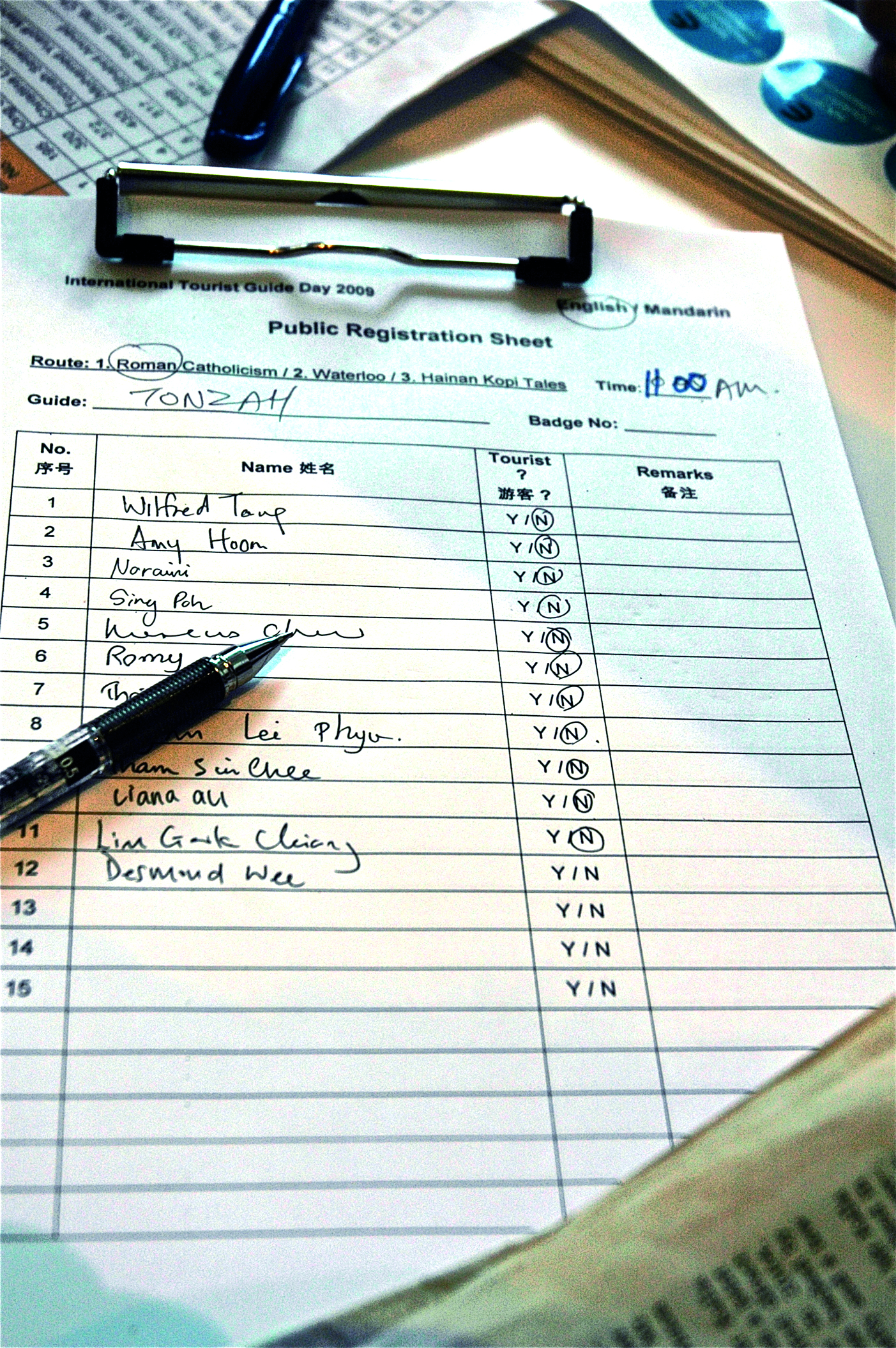

It was International Tourist Guide Day on 21 February 2009 and in commemoration of the event through collaboration with the STB, free walking tours of three designated heritage areas were conducted by more than 80 Singaporean tour guides.

Registration and assembling of tours were coordinated on the grounds of the National Library where excited participants gathered. What was revealing was an interesting question posed on the registration sheet, “Tourists?”, of which all the participants answered in the negative, with the exception of “No. 12” who seemed unable to answer the question. In my subsequent hunt for “obvious” tourists, I found a German who would not consider himself a tourist as he was married to a Singaporean, and a Polish woman who asked the person at the registration desk to recircle the “N” instead of the “Y” because she considered herself an expatriate in Singapore. At the end of the day, I finally found an American couple who said explicitly that they were tourists and were elated to have chanced on the occasion while walking by.

I wonder what kind of statistic could be obtained from the curious question posed to the thousands of locals who thronged there. The event was conceived by the tourism board for locals, but the intrusion of touristic concepts in terms of the activity and the purveyors of tourism were not central to the discourse. In an ironic way, it was ostensibly a tour which did not constitute tourism, nor was it meant for tourists. Yet, it is also in this respect of ambiguity that challenges notions of tourism beyond the commonly agreed borders and the nuanced practices of the actors at play.

Performing Tourist

In an article in the Straits Times on 18 April 2009 entitled “Rediscover Singapore, says URA”, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) as “Singapore’s master planning agency… is kicking off a string of initiatives to plan for the eventual recovery and to expand its own role locally and globally. It is also hoping to reacquaint Singaporeans with the city and renew their love for it, National Development Minister Mah Bow Tan said”. He added:

“So let’s do what we would like to do overseas – let’s do shopping, our eating, our sightseeing – let’s travel around Singapore, revisit the places we have not visited for a long time, maybe even discover some new surprises.”

“Rediscover Singapore” is also the name of a compact booklet highlighting places of interest for Singaporeans to venture to. In the introduction of the publication, Jason Hahn (2003) writes:

“[I]n our rush to explore the world, all too often, we overlook the fact that we are strangers to our own backyard. In some ways, it’s almost trendy to trumpet the fact that we don’t even know what’s beyond Orchard Road or our block of flats. As phenomena go, this is nothing new. There are born and bred New Yorkers who’ve never been to the Statue of Liberty, while millions of tourists travel around the globe to visit her. But, if you ask us, that’s a shame. As the Chinese writer, Han Suyin, once observed, the tree is known by its roots… And while it may seem odd, at first blush, to be producing a publication such as this, it became very clear right at the beginning that Singaporeans are very unfamiliar with many of these places. In a quixotic sense then, this magazine is about Singapore for Singaporeans.”

The institutional attempt and discursive implement of identity building seem rather apparent. It is about the consumption of place (and practice) as identity, but it is also about consumption of identity in place, evidenced in a coordinated planting of human roots into spaces of familiarity and belonging. However, the kinds of identities that are being determined in terms of inclusionary and exclusionary space bring to the fore the complexities of “love” for the city. Relph (1976, p. 49) in Place and Placelessness elaborates on “insideness” and “outsideness” in terms of human experience of place wherein “[t]o be inside a place is to belong to it and identify with it, and the more profoundly inside you are the stronger is the identity with the place”. Why is there a pride in being putatively oblivious to the outskirts of downtown and cultivating an inside-outside confusion? And what is this quixotic sense: the ideal, the romantic or the delusional? More than being about Singapore for Singaporeans, the discourse is laden with how to be “authentically” Singaporean and how to perform Singaporean identity within compressible spaces. It is specifically the renewal of love and the rediscovery of the modern city which are becoming tourism and identity simultaneously.

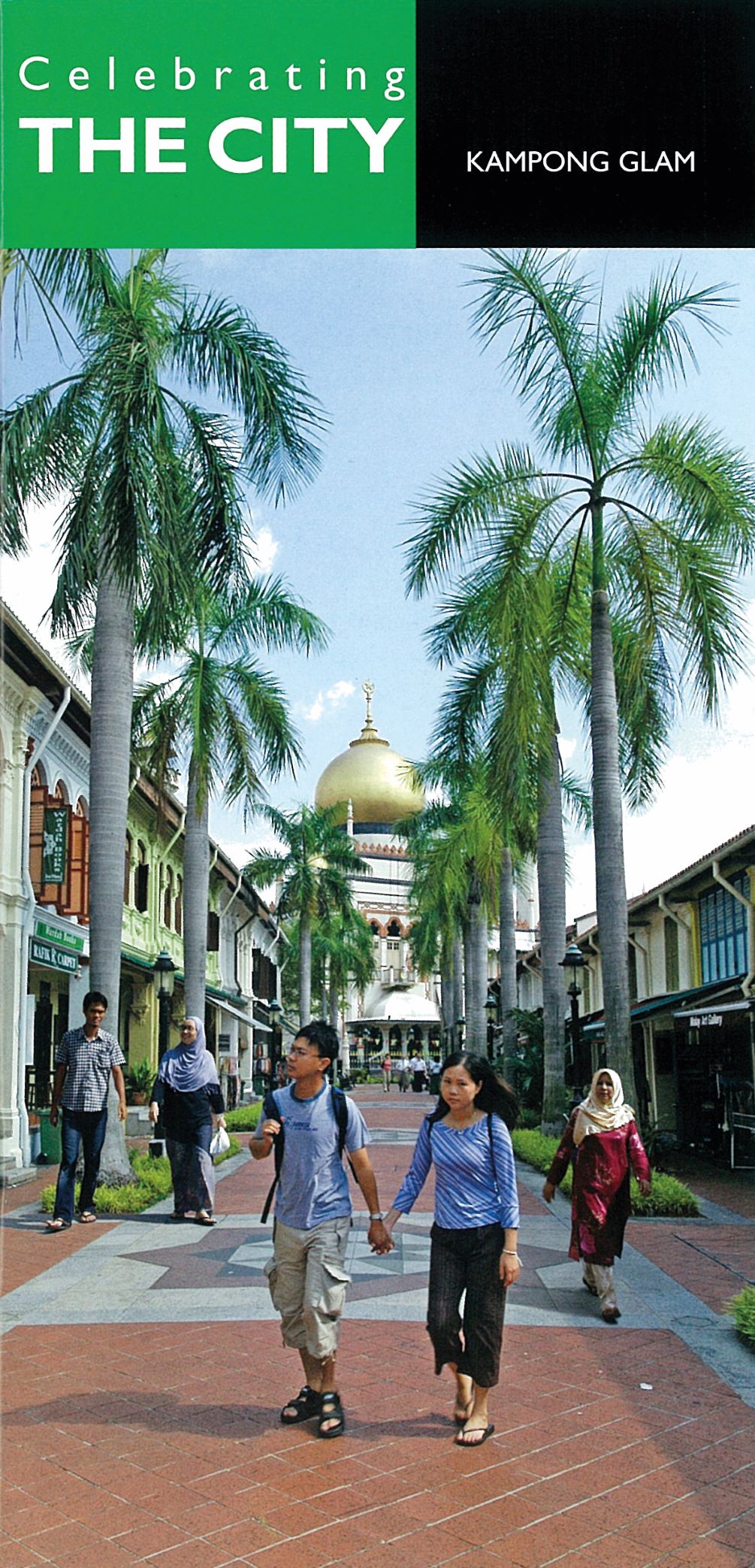

Figure 7 is a walking tour map and guide of the “Malay ethnic” area known as Kampong Glam. It is one of four ethnic enclaves demarcated both in terms of national rhetoric to mark multiculturalism as a melange of Chinese, Malay, Indian and Other, as well as supporting tourism place designation. Unlike other guides similar to this one published by STB, the URA version has a significantly Singaporean appeal. In the foreground is a young “Chinese” couple exploring the “traditional” Malay place exemplified by three “Malays” in the background flanked by two rows of shop houses, the women wearing baju kurung and donning tudungs over their heads. The ethnicities in question are crucial to highlight the inherent representations of Chinese as Singaporeans performing tourism within a systematic, othered Malay space. But what if the Malays in the background were also performing tourist rather than performing local? Would there be a difference in comprehending the loci of a contextualised Singaporean space? I suppose the ideal place performance envisaged for the audience of this pamphlet would comprise the initial will to be there, the (re)discovery process of an exotic culture and a consequential knowledge fulfilment by way of experience which produces a greater place identity. The quest for identity is revealingly its acquisition at once, with the performance constituting the thing it is performed for. In a “quixotic” sense, Singaporean identity is seemingly about performing Singaporeanness through tourist practice.

Singaporean Under the Merlion

For a while I stood under the Merlion doing a vox pop, trying to understand what Singaporeans thought of the Merlion. I realised the answers were standardised depending on whether I was a tourist or a local. As a tourist, it was portrayed the way Thumboo’s (1979) “Ulysses” would describe it, “This lion of the sea/This image of themselves” in multicolour splendour, and as a local, it was closer to the “Merlion” of Sa’at (2005): “how its own jaws clamp open in self-doubt”, “so eager to reinvent itself”. In answer to the “where are you from?” question, I would like to say after some contemplation, that I am a tourist from here. I have written elsewhere (Wee, 2009) that, on the one hand, it would seem that the determined national imperative to acquire a particular identity has seen ramifications that question its very construction, but on the other, the same national ideology that expends its energies in producing contrived identities is also capable of producing other forms of ironic and even affectionate identifications. The modern Merlion, albeit filled with conflicts and uncertainties and somewhat depressing, is also more real and aware of the incessant search for identity embedded as everyday discourse within itself. The Singaporean under the Merlion taunts the reflexive self as person, concept, feeling and, most crucially, the becoming of each or all given the locality.

In the same way through performance, tourism and its actors are constantly in states or conditions of becoming, reevaluating and repossessing particular jurisdictions of space and cultivating emergent forms of identity through meaningful contestations. If we look at everyday life as “the starting point of inquiry and the rationale for touristic behaviour”, (McCabe, 2002, pp. 66–67), then the place performance of Singapore as a tourist city through its branding confounds identity in terms of how we identify tourists and how tourists identify themselves. Tourism is being incorporated into the every day and vice versa in ways which they are being reproduced through embodied practices. The positioning of “experience” in Singapore as creative space for local consumption through the Uniquely Singapore and the Rediscover Singapore campaigns provoke the collapsible nature (Simpson, 2001) of tourism and the every day. This reproduction of space through the lens of the tourist and the local confuses the localities of consumption and acknowledges routes as performance.

By looking at how tourist performance “affords” local performance, this paper acknowledges a deeper enquiry into the agency of tourism rather than producing answers. It also investigates the bigger question, if the nomenclature of tourist-local is not already coalesced into a tourism-scape of buzzing practices. Baerenholdt et al. (2004) suggest the possibility “[t]o leave behind the tourist as such and to focus rather upon the contingent networked performances and production of places that are to be toured and get remade as they are so toured”. The emphasis on tourist practice instead of dealing with the fuzzy tourist, rather than an eschewal of definition, is a reception of a multicoded performance of place, unceasingly sprouting routes. In this respect, “becoming tourist” is also about “becoming local”, which is also about “becoming tourist”. They are about performances amalgamated in multiform, mystifying each other and reinforcing the sense of place as they are being defined.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Philip Long, Principal Research Fellow, Centre for Tourism and Cultural Change, Faculty of Arts and Society, Leeds Metropolitan University, in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Alfian Sa’at, One Fierce Hour (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1998). (Call no. RSING S821 SAA)

“‘Beyond Words’. The Next Phase of Uniquely Singapore Brand Campaign, Breaks New Ground,” Singapore Tourism Board, accessed 18 July 2006.

Chua Beng Huat and Eddie C.Y. Kuo, The Making of a New Nation: Cultural Construction and National Identity in Singapore (Singapore: Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore, 1991). (Call no. RSING 959.57 CHU)

David Crouch and Luke Desforges, “The Tourist Encounter,” Tourist Studies 1, no. 3 (2001), 253–70.

Desmond Wee, “Singapore Language Enhancer: Identity Included,” Language and Intercultural Communication 9, no. 1 (2009), 15–23.

Douglas Kellner, “Popular Culture and the Construction of Postmodern Identities,” in Modernity and Identity, ed. Scott Lash and Jonathan Friedman (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992)

E.A. Devan, Questioning Evolution and Progress, 22 November 2006.

E. Danzer, No Title, photograph, 2006, OnAsia. (Image Number: eda00484)

E. Su, No Title, photograph, 2006, OnAsia. (Image Number: esu00181)

Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness (London: Pion, 1976)

Edwin Thumboo, Ulysses by the Merlion (Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books, 1979). (Call no. RSING 828.995957 THU)

Erik Cohen, “ A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences,” Sociology 13, no. 2 (1979), 179–202.

J. Boh, No Title, 2009, photograph, On Asia, (Image Number: jbo00131)

J. Lengkeek, “A Love Affair With Elsewhere: Love as a Metaphor and Paradigm for Tourist Longing,” in The Tourist as a Metaphor for the Social World, ed. G. Dann (Wallingford: CABI Publishing, 2002), 189–208.

James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997)

Jorgen Ole Baerenholdt et al., Performing Tourist Places (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004). (Call no. RBUS 338.4791 PER)

Ken Simpson, “Strategic Planning and Community Involvement As Contributors to Sustainable Tourism Development,” Current Issues in Tourism 1, no. 4 (2001), 3–41.

L. Duggleby, No Title, photograph, 2006, OnAsia. (Image Number: ldu03821)

Marie-Franðcoise Lanfant, John B. Allcock and Edward M. Bruner, eds., International Tourism: Identity and Change (London: Sage, 1995). (Call no. RBUS 338.4791 INT)

Mimi Sheller and John Urry, eds., Tourism Mobilities: Places to Play, Places in Play (London: Routledge, 2004). (Call no. RBUS 338.4791 TOU)

Pamelia Lee, Singapore, Tourism and Me (Singapore: Pamelia Lee Pte Ltd., 2004). (Call no. RSING 338.47915957 LEE)

Paul Gilroy, Black Music, Ethnicity, and the Challenge of a Changing Same (London: Verso, 1994)

Peter Schoppert, “The Merlion & Other Monsters: Some Notes on Singapore’s Moving Monuments,” in Lim Tzay Chuen, Mike (Singapore: National Arts Council & Singapore Art Museum, 2005). (Call no. RSING q731.86 LIM)

S. McCabe, “The Tourist Experience and Everyday Life,” in The Tourist as a Metaphor for the Social World, ed. G. Dann (Wallingford: CABI Publishing, 2002), 1–18.

Stuart Hall, “Who Needs Identity?” in Questions of Cultural Identity, ed. Stuart Hall and and Peter Du Gay (London: Sage, 1996)

Tim Edensor, “Performing Tourism, Staging Tourism: (Re)producing Tourist Space and Practice,” Tourist Studies 1, no. 1 (2001), 59–81.

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore), Rediscover Singapore: An Explorer’s Guide to Funky Finds, Fab Fun and Fantastic Food (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority by Media Corp Publishing Pte Ltd, 2003). (Call no. RSING 959.57 RED)

Valene L. Smith, ed., Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1977).