The Educational Movement in Early 20th Century Batavia and Its Connections with Singapore and China

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Oiyan Liu explores how movements of people, their thoughts and activities across Dutch-ruled Batavia, British-ruled Singapore and China were related to one another and how educational exchanges mutually shaped the political visions of diasporic Chinese.

The above quote is an extract from Juin Li’s lecture entitled Chinese Emigrants and Their Political Ability which was delivered at Jinan College in Nanjing, China, on 8 February 1922. Jinan, established in 1906, was the first institution for higher education that was especially opened for overseas Chinese. Functioning under China’s central government, the school aimed to integrate the Chinese from Southeast Asia and trained Nanyang Chinese to become agents who would then spread China’s political influence overseas. The school, which was established after the educational movements in the Dutch East Indies and British Malaya had been initiated, first approached advocates of the educational movement in Java for institutional integration. Soon thereafter, Jinan also started to recruit students from British Malaya, particularly Singapore.

In this essay, I seek to understand how movements of people, their thoughts and activities across Dutch-ruled Batavia (now Jakarta), British-ruled Singapore and China were related to one another. I analyse the circumstances under which these triangular relations intensified, and the conditions under which this process of integration weakened. More interestingly, I attempt to understand how educational exchanges mutually shaped the political visions of diasporic Chinese. This essay concentrates on the case of Batavia and examines how the educational movement of the Dutch East Indies Chinese was connected to the educational movements in Singapore and China.

The Educational Movement in Batavia

“China is so much… larger than Japan! How great could

we become if the great China reorganises! We could

become the most powerful nation in the world, but first we

need education to reach that goal.”1

This quote is taken from the notes of L.H.W. van Sandick, an inspector at the Domestic Governance Department of the Dutch colonial government, who investigated essays that were written by students of the Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan school in Batavia. Dating back to 1909, this source reveals that during that period, Indies Chinese students felt that they were and wanted to be part of China. They positioned the status of China and the Chinese, including those residing overseas, and envisioned (by comparing themselves with Japan as inspiration) China becoming the most powerful entity in the world through education.

The movement for modern Chinese education in Batavia started at the turn of the 20th century when Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan (中華會館; hereafter THHK), the first pan-Chinese association in the Indonesian archipelago was established in 1900 and opened its school named the “Tiong Hoa Hak Tong” (中華學堂). Founding members included Lee Hin Lin, Tan Kim Sun, Lie Kim Hok and Phao Keng Hek.2 The school was funded with an annual support of 3,000 guilders from the Chinese Council, and aimed to provide free education for all children of Chinese descent.3

While some studies claim that THHK’s educational programme was meant to reform outdated practices within the Chinese community,4 I believe that the educational movement should be considered a public reaction of the local Chinese towards anti-Chinese colonial policies of the time.5 Under the new state policy, the Dutch provided education and subsidies for indigenous inhabitants but with the exception of a few Indies Peranakan Chinese, they continued to deny education to the Chinese communities. Criticising the Dutch government for not providing widespread education for children of Chinese descent, THHK made use of funds that had been self-generated by the local Chinese as a political tool to fight for equal rights under the Dutch colonial administration.

THHK was the first Chinese educational institution in Java that raised worries among the Dutch. The association played an important role in stimulating the educational concerns and political movement in Java.6 In his pertinent essay “What Is a Chinese Movement” written in 1911, Dutch lawyer Fromberg observed that local Chinese desired equal education, equal treatment among races, and equal law in Java.7 Indies Chinese took the case of Japan as an example to evaluate their own position. It was believed that based on ethnic backgrounds, the Japanese in the Indies should belong to the racial category of “Foreign Orientals” (Vreemde Oosterlingen). However, in the late 1890s, the Japanese, as the only Asiatic community that was granted the same judicial status as Europeans, were incorporated in the category of “Europeans” in the Dutch census. It can, therefore, be inferred that “colour” was not the most important parameter for defining “race”. Instead, it was the “civilised status” that formed the criterion for racial categorisation. Looking at the Japanese as an example, Indies Chinese believed that education would improve the political outlook for the Chinese in Java in the long run. Hence, even without the support of the Dutch government for education, the Chinese in Java took the initiative to establish their own school which allowed all Chinese children of various social classes to attend.

The Singapore Connection

It was the educational movements in Singapore and China that had an impact on the shaping of Java’s educational movement, which was initiated by the Indies Chinese. Singapore, in particular, played an important role in framing the educational system of THHK in its initial stages. Straits Chinese representatives visited schools in Java regularly and the Chinese in Java declared that “they derived the germ of their ideas on [education] from Singapore”.8 Lim Boon Keng, who started promoting modern Chinese education during the Confucian revival movement in the Straits Settlements at the end of the 19th century, played an important role in the initial stages of the educational movement in Java.9 A report shows that Lim Boon Keng appointed THHK’s first principal.10 He also appointed a teacher for THHK.11

In 1902, on the occasion of celebrating the anniversary of the THHK school, The Straits Chinese Magazine, edited by Lim Boon Keng and Song Ong Siang, acknowledged THHK’s contribution in awakening the Indies Chinese and praised the spirit of reforming the Dutch East Indies.12 Although not explicitly stated in published matters, connections between pioneering leaders of the educational movements in the Straits Settlements and the Dutch East Indies proved that both movements were connected. Soon after THHK’s foundation, the association extended its reach to Batavia with the institutionalisation of the English school called Yale Institute. Yale Institute was supervised by the THHK, but founded by Lee Teng-Hwee, a Batavia-born Peranakan Chinese who had started an English school in Penang with Lim Boon Keng after his studies at the Anglo-Chinese School in Singapore.13

The Dutch colonial government suspected that their subjects, through their connections with the Straits Chinese, would become more supportive of British rule. They were particularly threatened by THHK’s influence in fostering the idea that Dutch rule was less favourable than the governance of the British, their imperial competitor. THHK’s curriculum was similar to that in schools in the Straits Settlements. These schools taught Chinese and “modern” subjects, e.g., mathematics, physics and (when funding permitted) English.14 Initially, THHK wanted students to learn Dutch, but it soon proved to be impossible.15 Hiring Dutch instructors was too expensive, and the Dutch government did not allow the Chinese to learn and speak Dutch because they wanted the language to be synonymous with the rulers and positions of authority.16 The social stigma and lack of funding to learn Dutch caused THHK to teach English as a European language instead.

Integrating with China: Jinan

Connections with political activists from China such as the reformer Kang Youwei and the revolutionary Sun Yat-sen who were active in Southeast Asia further intensified the integrative process among Chinese in Singapore, Batavia and China. Ideological integration with China sprouted in Nanyang through contacts with these political exiles, but educational integration with China officially only started in 1906 when the Qing Empire established Jinan Xuetang (暨南學堂) in Nanjing. Jinan was the first school for huaqiao (overseas Chinese) in China, and was intended to be the highest educational institution for all overseas Chinese. Its establishment could be considered a milestone for educational integration by which the Chinese government officially reached out to Nanyang. Jinan’s mission was to spread Chinese culture beyond China’s territorial borders by nourishing returning huaqiao who would then further spread the spirit of Chinese civilisation to other places.17

Pioneers from Java

The first batch of students at Jinan came from Java.18 The Qing Empire and THHK had existing educational exchanges prior to the establishment of Jinan. By way of the Department of Education, it allowed THHK to request qualified teachers with certification from China to teach in Java.19 The THHK committee also selected students who would be sent to China.20 In China, these students received further education under the auspices of the Chinese government. The purpose was to nourish ties of Indies born Chinese towards “the motherland”, and to keep China’s national enterprises running. The press reported that the Chinese in the Indies were “stepchildren” who were abandoned by the Dutch Indies government but who were awakened and recognised by their own father (i.e., China) who had been previously “dormant”.21 It would be incorrect, however, to assume that the Nanyang Chinese enthusiastically embraced the Chinese government. It was noted that the Indies Chinese reacted to Qing’s outreach to Java with suspicion. One source reported “at first, our association [THHK] did not think of sending our kids to China, because we did not know if we could count on the Chinese state”.22 Questioning the accountability and reliability of the Qing state was understandable, for until 1893 Chinese subjects who left Qing territory without imperial approval were considered traitors of the Chinese state.23

On 21 February 1907, the first 21 students went to Nanjing.24 The Chinese court expanded its educational integration with other Chinese communities in maritime Southeast Asia in the second round of student recruitments. In 1908, Jinan recruited 38 students from Java and 54 students from Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Penang. From 1908 onwards, the Qing regime requested that 45 Straits Chinese be sent to Jinan annually.25 The first students from Singapore include Lee Kong Chian, who had studied at Jinan for two years before furthering his studies at Qinghua Xuetang.26 Based on the curricula of Jinan, it can be concluded that the school not only aimed at nourishing national consciousness, but also training students to become leaders in the fields of finance, commerce and education – fields that were considered crucial by both China and Nanyang Chinese in order to compete with the Western imperial powers.

Jinan: 1917–Late 1920s

Jinan closed down after the fall of the Qing Empire but reopened in 1917.27 After its reopening, the school increasingly modelled its curricula to meet the requirements of both the Nanyang Chinese as well as “national needs”. During its foundational years, Jinan focused on stimulating nationalistic sentiments. Throughout this period, the school concentrated on equipping students with skills that were needed to prosper in commerce and trade. Although teaching students professional skills was ostensibly a primary role, there was a persistent aim of inculcating in them a love for “the motherland” (i.e., China). Besides professional skills, Jinan incorporated the national ideology (Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People) in courses concerning racial issues in its curricula.28

Despite the increasing integration with the Nanyang Chinese, Jinan’s aim to become a centralising force for all schools in Nanyang did not go smoothly. In 1930, Liu Shimu, an administrator at Jinan and previous principal of a Chinese school in Dutch-ruled Sumatra, felt that huaqiao education was not well coordinated or unified. Liu Shimu believed that self-government of schools in Nanyang obstructed the integration of Nanyang with China. Other factors that caused problems were lack of facilities, insufficient financial means and the presence of unqualified teachers.29

Colonial Paranoia and Counter-Integrative Policies

Although organisational problems and the increasing desire for autonomy among overseas Chinese obstructed China’s centralisation project, according to Chinese authorities, integration was mainly hampered by colonial forces. Since the establishment of Republican China, colonial forces had been enforcing stricter measures on educational bodies located in their territories. In the Straits Settlements, for instance, the British Legislative Council launched an education bill for the first time on 31 May 1920. The bill gave the British government official control over Chinese schools. Schools were allowed to continue functioning, but they were obliged to remove their political ambitions and curricula that contained any Chinese nationalistic content.30

The Dutch implemented counter-integrative measures a decade earlier than the British. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Dutch were already aware of the political indoctrination of the Indies Chinese through their connections with the Straits Chinese and Jinan. In 1909, Van Sandick reported that “[t]he most pressing issue of this private education [i.e., THHK] for Chinese children is not the instruction of the mandarin-language, not history, nor geography, but ideas. Ideas that indoctrinated into the mind of the Chinese youth”.31 The spread of ideas was described as the “yellow peril”. Borel, renowned specialist on Chinese matters in the Dutch Indies, expressed the feeling that the National Chinese Reader used in Chinese schools was completely filled with modern ideas and evoked nationalist consciousness. Yellow peril, therefore, does not refer to supremacy of military power, but refers to the threat of modern ideas. He expressed concern, and estimated that by the end of the first decade approximately 5,000 students were influenced by these ideas.32 It was during this period that the Dutch feared losing their authority over the Indies Chinese. The Dutch press expressed concern that Chinese movements in the Indies would endanger Dutch sovereignty in the Indies, mainly because these movements were nurtured from outside forces, particularly from China. Some Dutch authorities suggested revising the laws to secure political legitimacy over the Chinese. The Dutch were concerned with attracting the loyalty of Chinese settlers because they were regarded as the most industrious residents in the colony.33

Dutch paranoia of losing its political authority over its subjects made the colonial government modify its policies. In order for the Dutch to maintain political support of the Indies Chinese settlers, the colonial government competed with the Chinese government to provide state-sponsored education. In 1908, just about one year after pioneering students from Java sailed off to Jinan, the Dutch government established the “Hollandsche Chineesche School” (HCS; Dutch Chinese School) so as to create a setback for the Indies Chinese integrative tendencies towards aligning itself with China. Dutch motives for opening HCS were to compete with THHK and the Chinese government on controlling education. HCS’s curriculum aimed at “dutchifying” the Indies Chinese while THHK’s curricula promoted sinification.

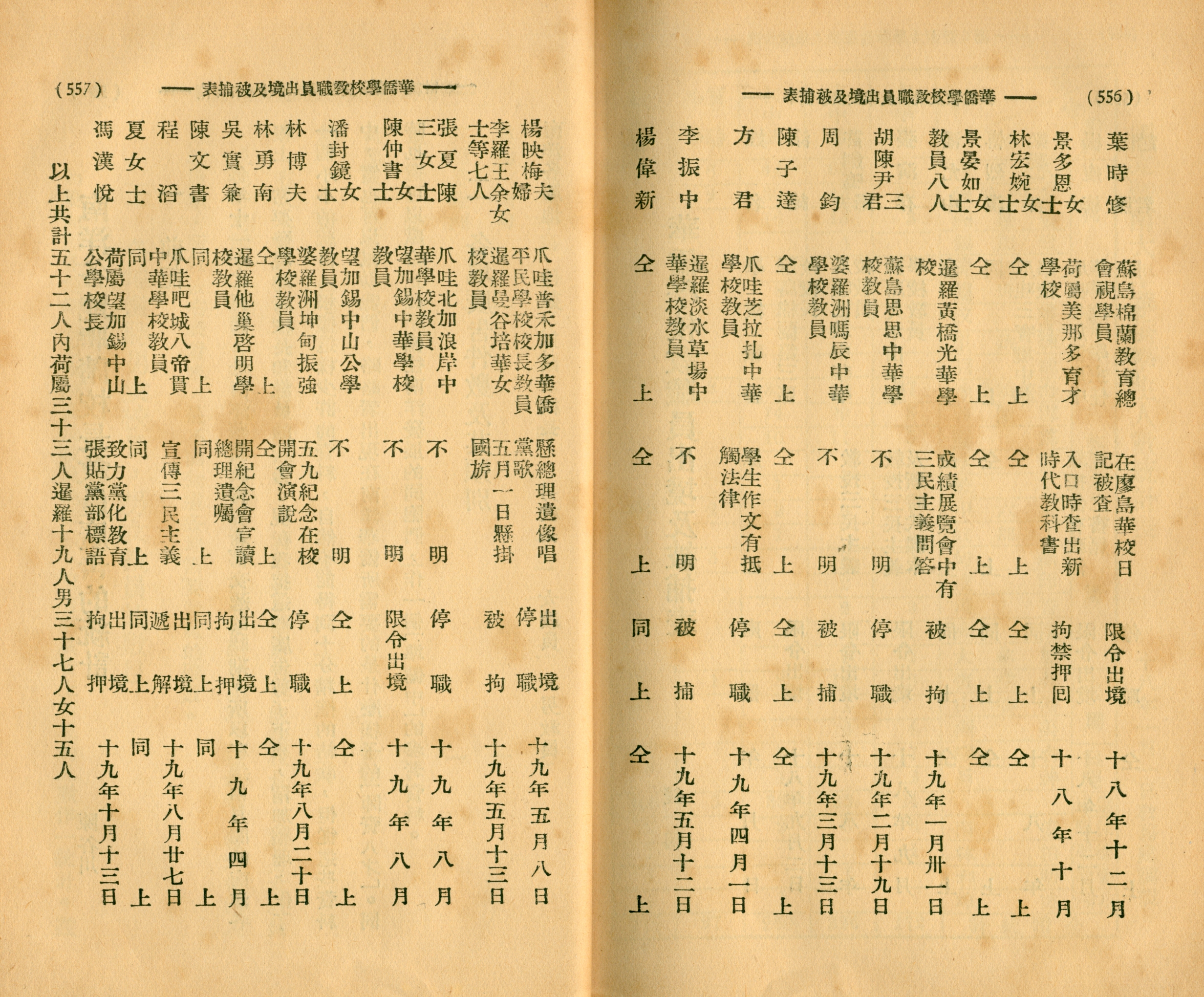

HCS’s foundation helped roll back the integrative process with China but was never successful in completely erasing the impact of Chinese schools on the political orientation of the Indies Chinese. A report on detained and expelled instructors reveals that Dutch paranoia of the threat of Chinese schools still persisted two decades after the establishment of HCS. The document Huaqiao xuexiao jiaozhiyuan chujing ji beibubiao reveals that in 1929 the Dutch punished 33 instructors.34 The list of names included mostly teachers from Java. All instructors were punished for political reasons, including teaching political ideologies (such as Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People) and using political tutorials.

Instructors were mostly expelled from the Indies. In a few cases instructors were detained. Others were forced to stop teaching for unclear reasons. Students were investigated as well, and in one case a teacher was forced to leave his post after it was discovered that a student wrote an essay about judicial equality.35 These cases show that, even after two decades, the Dutch still struggled with the threat of Chinese schools in the Indies.

Ambiguous Missions

What caused this colonial paranoia to emerge? What visions did institutional exchanges create? In 1927, Jinan released a public announcement, which stated that it wanted to prevent any misunderstanding with the imperial powers. The school stated that its mission followed Sun Yat-sen’s political framework that aimed at nourishing generations of Nanyang Chinese with good personalities, knowledge, interest and the capacity to survive. Jinan claimed that its task was to ensure that Chinese settlers and sojourners who were subject to colonial rule would obtain equal political status and economic treatment. Jinan stated: “We want to prevent misunderstanding of colonial governments, that is: we do not want them to think that Jinan’s national establishment is aimed at constituting a type of statism or imperialism. We do not want colonial powers to think that we instil students with thoughts of invading territories of others. We do not want them to think that once our students graduate and return to Nanyang, they will disrupt the authority of colonial rule and stir revolutions against colonial governments with indigenous inhabitants.”36

This document, written in Chinese, was presumably mainly targeted at Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Instead of employing nationalistic terms that Jinan used in its foundational years, Jinan now used imperialistic vocabulary and attempted to distort its imperialistic tendencies by differentiating the Chinese government from Western imperialist powers. Instead of having imperialist and nationalist ambitions, Jinan claimed that the Guomindang’s goal was simply to achieve freedom and equality of China and have its huaqiao enjoy freedom in international settings. They urged the colonial powers to allow Chinese in Southeast Asia to manage Nanyang society in an autonomous manner.37

Despite attempts by the Chinese authorities to invalidate Jinan’s imperialist and nationalist tendencies, British intelligence reports revealed that Jinan did stir up anti-colonialist sentiments among its students. The institution was particularly against Britain, which was considered the greatest colonial power at the time. The British government confiscated correspondence between Nanyang and China. Secret letters from a teacher at Jinan, who previously taught in Batavia, complained that “school registration in Malaya and the ‘cruel rules’ of the Dutch in Java are examples of foreign oppression which will destroy the foundation of China”.38 Intelligence reports also revealed that Jinan nurtured students with visions of a future government that would be ruled by the Nanyang Chinese. On 8 February 1922, Juin Li, lecturer at Jinan University, expressed the following:

“Look at the map of Asia; I have observed that in the near

future there will spring up one new independent country, the

Malay Peninsula, the Straits Settlements. The masters of this

new political division will certainly be Chinese. The British

power in Egypt and India is crumbling, so the tide of revolt

will spread to the East, and the Malay Peninsula will be the

first to catch its new influence…. I do not advise you to revolt

against the British authority at once, because first you must

be prepared yourself to organise a government and conduct

political affairs, otherwise even if the British authority should

be overthrown, you will be helpless. Now is the time for

you students to build up your political ability, because the

future masters of the Malay Peninsula are you students of

this college.” 39

This shows that educators at Jinan encouraged and prepared its students to become pioneers of anti-colonialism in Southeast Asia. Contrary to its public claim that it did not encourage overseas Chinese to challenge colonial rule, it is evident that Jinan did stimulate anti-colonialism. By the 1920s, this institution intensified its anti-British attitudes and claimed that the Chinese were the first people that developed Malaya before the British took over. Jinan stated that “the Chinese were better off in Malaya before the English came.… We Chinese opened Malaya – it ought to be ours”.40

In short, even though Jinan publicly claimed that unlike Western colonial powers, China did not aim at encroaching on non-Chinese territory, confidential reports show that it did hope to expand its power by integrating with the Nanyang Chinese whom they stimulated to take over the power of the colonial rulers. China’s non-imperialist claim was therefore contradictory, for it hoped to gain control over territories which were not under China’s sovereignty through the intervention of overseas Chinese. The colonial powers, therefore, sought ways to counter integration with Jinan, the primary institution that aimed at training students to play key roles in a Southeast Asian society that would not be ruled by the colonial powers.

Conclusion

This essay attempts to map out the interconnectivity among educational movements in Dutch Batavia, British Singapore and coastal China. By looking at institutional movements of people, their thoughts and activities across colonial and imperial port cities, the article offers an analysis of how educational exchanges shaped political visions. Singapore played an important role in guiding the initial stages of the movement in the Dutch Indies. Educational movements in Batavia and Singapore also helped shape the educational system for overseas Chinese in China. Jinan, the first post-primary school for overseas Chinese, was opened after the educational movements in the Dutch Indies and British Malaya had started. Jinan launched institutional integration with the Nanyang Chinese and nourished its students with visions of a greater China, anti-colonialism and a future Malaya that was ruled by people of Chinese descent. On the other hand, by attracting the support of the Nanyang Chinese, China continually changed its mission and curricula according to the needs of the Nanyang Chinese that seemed to be more concerned with obtaining more favourable professional benefits than to support China unconditionally.

This study reacts to two dominant approaches in present scholarship on the subject. It distorts the conventional perspective that the Nanyang Chinese uncritically and unconditionally supported the Chinese state. This romanticised view has been questioned by more recent studies that emphasise the autonomy of the Nanyang Chinese ambitions that were separate from China’s. Moreover, it illustrates weaknesses of both unidirectional approaches mentioned above. By using Chinese, Dutch, English and Malay sources, this essay concludes that visions of diasporic Chinese were continuously shaped by the dynamic relationship between educational movements in the Dutch Indies, Straits Settlements and China.

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of Associate Professor Eric Tagliacozzo, Department of History, Cornell University, USA, in reviewing this research essay.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2008)

National Library

REFERENCES

Ahmat Adam, The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of ModernIndonesian Consciousness (1855–1913) (Ithaca: Cornell SEAP Publications, 1995). (Call no. RSEA 079.598 ADA)

Anthony Reid, Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese: In Honour of Jennifer Cushman (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1996). (Call no. RSING 959.004951 SOJ)

Benny G. Setiono, Tionghoa Dalam Pusaran Politik (Jakarta: Elkasa, 2003). (Call no. Malay R 305.89510598 SET)

Cai, Y. (1927). Guoli Jinan xuexiao gaige jihua yijianshu. Shanghai Archives #Q240–1–270 (7)

Charles A. Coppel, Studying Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia (Singapore: Singapore Society of Asian Studies, 2002). (Call no. RCLOS 305.89510598 COP)

Chua Leong Kian, “Bendi yinghua shuyuan xiaoyou Li Denghui huiying Fudan daxue” 本迪英华书院小友李登辉汇英复旦大学.

Chua Leong Kian, “Lee Who? A Chinese Intellectual Worthy of Study,” Straits Times, 22 June 2008, 32. (From NewspaperSG)

He Qian 何倩, ed., Nanyang xuexiao zhi diaocha yu tongji 南洋华侨学校调查与统计 [Nanyang Overseas Chinese School Survey and Statistics] (Shanghai 上海:Shanghai Dahua yinshua gongsi 上海大华银画公司, 1930). (Call no. Chinese RDYTS 370.959 CNH)

Ji nan da xue 暨南大学, Nan yang hua qiao jiao yu hui yi bao gao 南洋华侨教育会议报告 [Nanyang Overseas Chinese Education Conference Report] (Shanghai 上海: [Chuban she que] [出版社缺], 1930). (Call no. Chinese RDTYS 370.959 CNT)

Jinan daxue bainian huayan, Xinjiapo xiaoyouhui liushiwu nian zhounian jinian te kan 暨南大学百年华诞, 新加坡校友会六十五周年纪念特刊 [The 100th anniversary of Jinan University and the 65th anniversary of the Singapore Alumni Association] (Xīnjiapo 新加坡: Xīnjiapo jinan xiaoyou hui chuban weiyuanhui 新加坡暨南校友会出版委员会, 2006). (Call no. Chinese RSING 378.51 JND)

Kwee Tek Hoay, The Origins of the Modern Chinese Movement in Indonesia (Ithaca: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, 1969). (Call no. RCLOS 301.4519510598 KWE)

L.H.W. van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China: Hunne Beteekenis Voor De Ontwikkeling Van Zuid-Oost-Azie, special Van Nederlandsch-Indie (‘s-Gravenhage: M.van der Beek’s Hofboekhandel, 1909). (Call no. RUR RSEA 959.80044951 SAN)

Lea E. Williams, Overseas Chinese Nationalism: The Genesis of the Pan-Chinese Movement in Indonesia, 1900–1916 (Glencoe: Ill, Free Press, 1960). (Call no. RDTYS 325.25109598 WIL)

Lee Ting Hui, Chinese Schools in British Malaya: Policies and Politics (Singapore: South Seas Society, 2006). (Call no. RSING 371.82995105951 LEE)

Leo Suryadinata, ed., Political Thinking of the Indonesian Chinese, 1900–1995: A Sourcebook (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1997). (Call no. RSING 305.89510598 POL)

Leo Suryadinata, ed., Prominent Indonesian Chinese: Biographical Sketches (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1995). (Call no. RSING 959.8004951 SUR)

Liang Qichao 梁啟超, “Yin bing shi he ji” ji wai wen “飮冰室合集”集外文 [Foreign languages of “the collection of ice room”] [Xia Xiaohong ji]. (Orignally published in Chenzhong, 12–13 Jan 1917, republished in Yinbingshi heji: Ji wai wen, vol. 2), 666–74. (Peking University Press, 2005), 666–74. (Call no. Chinese R C814.3008 LQC)

Liang Qichao 梁啟超, “Yin bing shi he ji” ji wai wen “飮冰室合集”集外文 [Foreign languages of “the collection of ice room”] [Xia Xiaohong ji]. (Orignally published in Chenzhong, 12–13 Jan 1917, republished in Yinbingshi heji: Ji wai wen, vol. 2), 666–74. (Peking University Press, 2005), 666–74. (Call no. Chinese R C814.3008 LQC)

Liu S., “Preface,” in “Nanyang huaqiao xuexial zhi diaoccha yu tongji” 南阳花桥大学学报母鸡与同济 [Journal of Nanyang Huaqiao University Henji and Tongji], ed. Qian H (Shanghai: Shanghai Dahua yinshua gongsi, 1930), 1–3.

Malayan Bulletin of Political Intelligence (MBPI)

Ming Govaars, Dutch Colonial Education: The Chinese Experience in Indonesia, 1900–1942 (Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centres, 2005). (Call no. RSEA 370.95980904 GOV)

Mona Lohanda, _Growing Pains: The Chinese and the Dutch in Colonial Java, 1890–_1942 (Jakarta: Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka, 2002). (Call no. RSEA 959.82004951 LOH)

Nio Joe Lan, Tiongkok Sepandjang Abad (Jakarta: Balai Pustaka, 1952). (Call no. RU RSEA 951 NIO)

Ong Hok Ham, “Sejaraj Pengajaran Minoritas Tionghoa,” in Riwayat Tionghoa Peranakan di Jawa (Depok: Komunitas Bambu, 2005), 89–103. (Call no. Malay R 305.89510598 ONG)

Philip A. Kuhn, Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times (Lanham: Rowman & Littlehead, 2008). (Call no. RSEA 304.80951 KUH)

Pieter Hendrik Fromberg, De Chineesche Beweging Op Java (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1911). (Call no. RSEA 301.45195105982 FRO)

Pieter Hendrik Fromberg, Mr. P.H. Fromberg’s Verspreide Geschriften (Leiden: Leidsche Uitgeversmaatschappij, 1926). (Call no. RDTYS 349.598 FRO)

Shijie Huaqiao Huaren Cidian 世纪华侨华人瓷店 [Century overseas chinese porcelain store] (Beijing: Beijing University Press, 1990)

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: University Malaya Press, 1967). (Call no. RCLOS 959.57 SON)

The Straits Chinese Magazine: A Quarterly Journal of Oriental and Occidental culture (Singapore: Koh Yew Hean Press, 1897–1907). (Call no. RRARE 959.5 STR; microfilm NL267; NL268)

Wang Gungwu, China and the Chinese Overseas (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991). (Call no. RSING 327.51059 WAN)

Wee Tong Bao, “The Development of Modern Chinese Vernacular Education in Singapore – Society, Politics & Policies, 1905–1941” (master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2001)

Wen Guanyi 文冠义, ed., Yindunixiya Huaqiao shi 银都妮西亚华侨城 [Yindu Nisia Overseas Chinese Town] (Beijing 北京: Haiyang chuban 海阳出版, 1985)

Yen Ching-Hwang, “The Confucian Revival Movement in Singapore and Malaya, 1899–1911,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 7, no. 1 (March 1976), 33–57. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Yen Ching-Hwang, The Overseas Chinese and the 1911 Revolution, With Special Reference to Singapore and Malaya (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976). (Call no. RSING 301.451951095957 YEN)

NOTES

-

L.H.W. van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China: Hunne Beteekenis Voor De Ontwikkeling Van Zuid-Oost-Azie, special Van Nederlandsch-Indie (‘s-Gravenhage: M.van der Beek’s Hofboekhandel, 1909), 255. (Call no. RUR RSEA 959.80044951 SAN). All translations are mine unless otherwise noted. ↩

-

“Chinese Schools in Java,” The Straits Chinese Magazine 10, no. 2 (June 1906): 100. (Call no. RRARE 959.5 STR) ↩

-

“Our Batavia Letter,” The Straits Chinese Magazine 6, no. 22 (June 1902): 88; “THHK school,” The Straits Chinese Magazine 6, no. 24 (December 1902): 168. (Call no. RRARE 959.5 STR) ↩

-

See for instance Kwee Tek Hoay, The Origins of the Modern Chinese Movement in Indonesia (Ithaca: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, 1969). (Call no. RCLOS 301.4519510598 KWE); Charles A. Coppel, Studying Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia (Singapore: Singapore Society of Asian Studies, 2002). (Call no. RCLOS 305.89510598 COP) ↩

-

This is based on primary sources I used. See for instance, “Chinese Schools in Java,” 100. The article states: “The Dutch Government has been advised to grant the Chinese the privilege of forming literary societies. Their purpose is to collect funds and to bring the blessings of education within the reach of every Chinese child, male, or female.” ↩

-

Lea E. Williams, Overseas Chinese Nationalism: The Genesis of the Pan-Chinese Movement in Indonesia, 1900–1916 (Glencoe: Ill, Free Press, 1960). (Call no. RDTYS 325.25109598 WIL) ↩

-

Pieter Hendrik Fromberg, De Chineesche Beweging Op Java (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1911), 1–65. (Call no. RSEA 301.45195105982 FRO) ↩

-

“Chinese Schools in Java,” 100. ↩

-

Yen Ching-Hwang, “The Confucian Revival Movement in Singapore and Malaya, 1899–1911,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 7, no. 1 (March 1976), 33–57 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: University Malaya Press, 1967), 235–6. (Call no. RCLOS 959.57 SON) ↩

-

Ming Govaars, Dutch Colonial Education: The Chinese Experience in Indonesia, 1900–1942 (Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centres, 2005), 55. (Call no. RSEA 370.95980904 GOV) ↩

-

van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 251. ↩

-

“Our Batavia Letter,” 53. ↩

-

Lee Teng-Hwee stayed in Batavia till 1903. He resigned on 1 May 1903, and left Batavia for the US in pursuit of a postgraduate degree in political economy at Columbia University. He was denied entry at the American border because of visa issues, and was deported to China with coolies in July 1903. He stayed in China after his deportation. See: New York Times, 20 July 1903, 1; “Our Batavia letter,” 53; “Shijie Huaqiao Huaren Cidian 世纪华侨华人瓷店 [Century overseas chinese porcelain store] (Beijing: Beijing University Press, 1990), 377; Lee, Shijie Huaqiao Huaren Cidian, 377; Chua Leong Kian, “Bendi yinghua shuyuan xiaoyou Li Denghui huiying Fudan daxue” 本迪英华书院小友李登辉汇英复旦大学 [Bendi Yinghua College student Li Denghui]; Chua Leong Kian, “Lee Who? A Chinese Intellectual Worthy of Study,” Straits Times, 22 June 2008, 32. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 252. ↩

-

Before the opening of its school, The Straits Chinese Magazine announced that THHK-school would be offering Dutch language courses. After its establishment THHK decided to offer English courses instead of Dutch. See: The Straits Chinese Magazine 4, no. 16 (December 1900); “Our Batavia Letter,” 53. ↩

-

Pieter Hendrik Fromberg, Mr. P.H. Fromberg’s Verspreide Geschriften (Leiden: Leidsche Uitgeversmaatschappij, 1926), 424. (Call no. RDTYS 349.598 FRO) ↩

-

Jinan daxue bainian huayan, Xinjiapo xiaoyouhui liushiwu nian zhounian jinian te kan 暨南大学百年华诞, 新加坡校友会六十五周年纪念特刊 [The 100th anniversary of Jinan University and the 65th anniversary of the Singapore Alumni Association] (Xīnjiapo 新加坡: Xīnjiapo jinan xiaoyou hui chuban weiyuanhui 新加坡暨南校友会出版委员会, 2006), 1. (Call no. Chinese RSING 378.51 JND) ↩

-

Jinan daxue bainian huayan, Xinjiapo xiaoyouhui liushiwu nian zhounian jinian tekan 暨南大学百年华诞, 新加坡校友会六十五周年纪念特刊 [The 100th anniversary of Jinan University and the 65th anniversary of the Singapore Alumni Association] (Xīnjiapo 新加坡: Xīnjiapo jinan xiaoyou hui chuban weiyuanhui 新加坡暨南校友会出版委员会, 2006), 30–33. (Call no. Chinese RSING 378.51 JND) ↩

-

van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 251. ↩

-

“Our Java Letter”, The Straits Chinese Magazine 11, no. 1 (March 1907), 34. ↩

-

Fromberg, Mr. P.H. Fromberg’s Verspreide geschriften, 425. ↩

-

van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 252. ↩

-

For a translated section of Xue Fucheng’s Proposal see Philip A. Kuhn, “Xue Fucheng’s Proposal to Remove Stigma from Overseas Chinese (29 June 1893)” in Philip A. Kuhn, Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times (Lanham: Rowman & Littlehead, 2008), 241–3. (Call no. RSEA 304.80951 KUH) ↩

-

van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 252–53. ↩

-

On 5 October 1908, 38 other boys from several schools in Java went to Nanjing. In 1909, the number of students from Java since the first dispatching to Jinan totalled 111. See van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 252–4; “Jinan daxue yu xinjiapo” 30–33. ↩

-

Lee Kong Chian: Entrepreneur, philanthropist, educator. He was head of Singapore ‘Zhonghua zhongshanghui’ (in Chinese) and head of ‘Xingma zhonghua Shanghui lianhehui’ (In Chinese). He was founder of certain Huaqiao schools and hospitals in Singapore. In the 1930s when Tan Kah Kee’s experienced difficulties in his business. Lee Kong Chian donated money to Xiamen University. In the 1930s–40s, Lee also established many primary schools and Guoguang High School in his home province, Fujian. He established the Lee Foundation that supports education. ↩

-

Yuan Shikai, president of republican China at the time was reluctant to reopen the school out of fear that the Guomindang opposition would thrive at Jinan where most students had participated in the 1911 Revolution. Lee Ting Hui, Chinese Schools in British Malaya: Policies and Politics (Singapore: South Seas Society, 2006), 28. (Call no. RSING 371.82995105951 LEE) ↩

-

Liu, “Preface,” in He Qian 何倩, ed., Nanyang xuexiao zhi diaocha yu tongji 南洋华侨学校调查与统计 [Nanyang Overseas Chinese School Survey and Statistics] (Shanghai 上海:Shanghai Dahua yinshua gongsi 上海大华银画公司, 1930), 1–3, 570–1. (Call no. Chinese RDYTS 370.959 CNH) ↩

-

Lee Ting Hui, “Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements 1920,” B78–79. ↩

-

van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 255. Emphasis added. ↩

-

van Sandick, Chineezen Buiten China, 255. ↩

-

Fromberg, Mr. P.H. Fromberg’s Verspreide geschriften, 431. ↩

-

This report also contained information about punishments by the Siamese government. Dutch and Siamese governments punished 52 Chinese instructors, out of which 19 instructors were penalised by the Siamese government. Generally speaking, Siamese punishments were more severe than Dutch punishments. See huaqiao xuexiao zhiyuan chujing ji beibubiao in Nanyang huaqiao xuexiao zhi diaocha yu tongji, ed. Qian He. Shanghai: Shanghai Dahua yinshua gongsi, 1930. Call no.: Chinese RDYTS 370.959 CNH ↩

-

This fascinating list releases names of detainees and “colonial violators”. It also reveals the names of schools where these instructors were employed, their punishments, and reasons and dates for punishment. Nanyang huaqiao xuexiao zhi diaocha yu tongji, ed. Qian He (Shanghai: Shanghai Dahua yinshua gongsi, 1930) (Call no. Chinese RDYTS 370.959 CNH) ↩

-

Cai Yuan Pei, 國立暨南學校改革計劃 意見晝. Minguo 16 (1927). Shanghai Archives #Q240–1–270 (7). ↩

-

Cai, 1927. All translations are mine unless otherwise noted. ↩

-

NAS, MBPI (1 April 1925), 22–25. ↩

-

NAS, MBPI, no. 8 (1 October 1922), section 41. Emphasis added. ↩

-

NAS, MBPI (1 April 1925), 22–25. ↩