Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee (1918–2010)

Kwa Chong Guan from the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies remembers the legacy, contributions and impact of former Finance, Defence and Education Minister Goh Keng Swee.

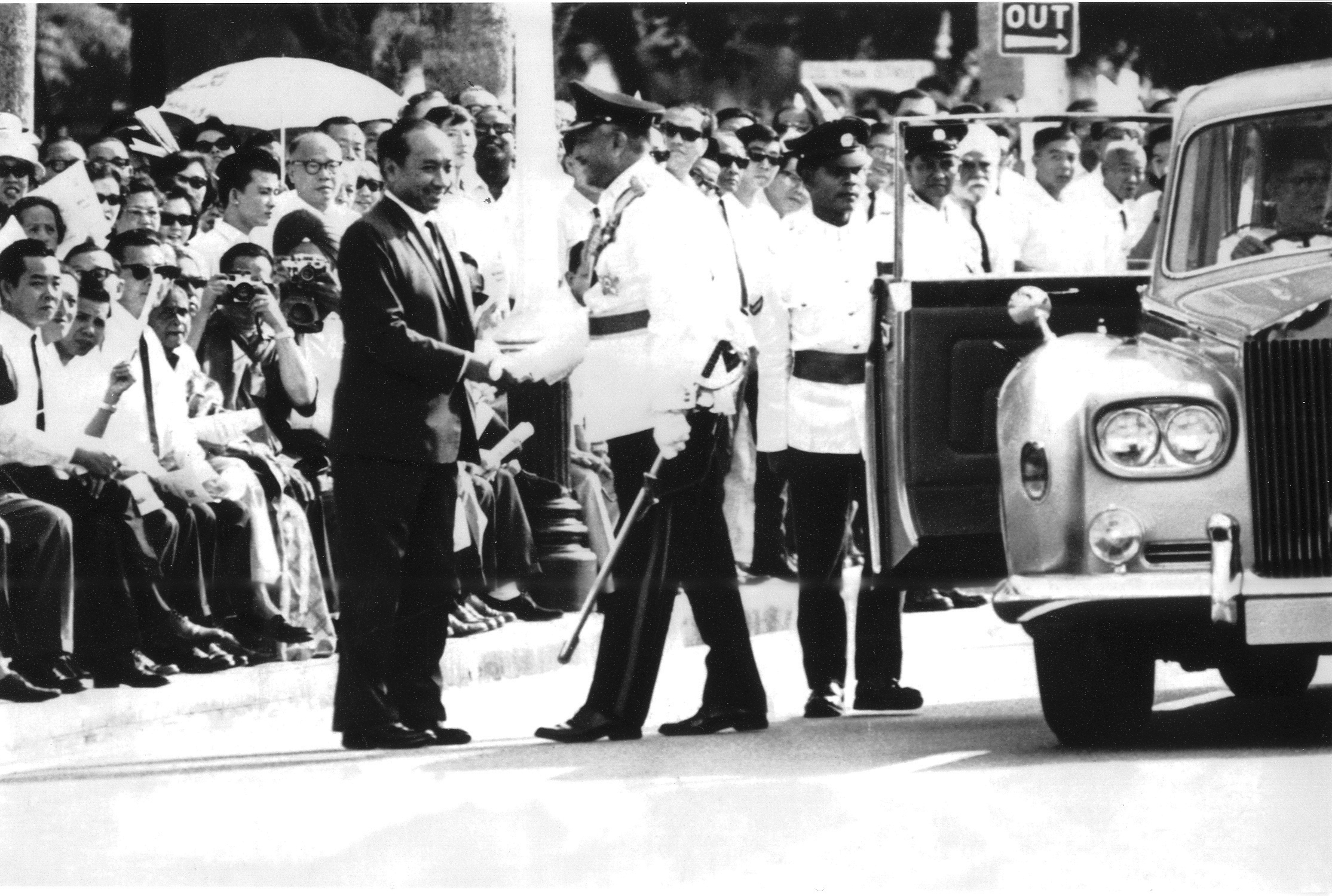

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at the state funeral for Goh Keng Swee: “Dr Goh was one of our nation’s founding fathers… A whole generation of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Goh left a lasting impression on everyone he encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him, and in his public career, initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore.

Our primary memories of Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anticolonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which he played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as the “Singapore Story”. Goh’s place in our writing of our history will in large part have to be based on the public records and reports tracing the path of his career.

As a public figure, Goh has left behind an extensive public record of the many policies that he initiated and have moulded present-day Singapore. But how did he himself wish to be remembered? Publicly, Goh displayed no apparent interest in how history would remember him, as he was more concerned with getting things done. Moreover, unlike many other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished to be remembered.

The deepest recollections about Goh must be the personal memories of those who had the opportunity to interact with him. At the core of these select few are the members of his immediate and extended family. In contrast to their personal memories of Goh as a family man are the more public reminiscences of his friends and colleagues. Many of these memories have become part of the social memory of the institutions that Goh was at the helm of during the course of his career in public service.

From the Open Public Records

Goh’s public career is amply documented in the open public records. His accomplishments after assuming office as Singapore’s first Finance Minister in 1959 were also recorded comprehensively. His pronouncements as a member of Parliament for Kreta Ayer Constituency from 1959 to 1984 are contained in Hansard. His policy statements during his various tenures as Minister of Finance, Defence and Education are necessary reading for an appreciation of Goh’s analyses of the challenges he perceived as confronting Singapore and his arguments to support his views. His policy pronouncements are essential for any assessment of his contribution to the making of government policy. But this is not what most people will recall or identify him with. The proceedings of Parliament that are transcribed in Hansard do not make for enthralling reading. Neither the Report on the Ministry of Education 1978, issued by Goh and his Education Study Team in 1979, nor his earlier 215-page 1956 Urban Income and Housing: A Report on the Social Survey of Singapore 1953–54 make easy reading. Different remembrances of Goh emerge depending largely upon which of the open public records one chooses to read and emphasise, and how critically and closely one examines the record for what it reveals or does not reveal.

However, many of the official public records of Goh’s contributions to policymaking remain classified. These are the Cabinet papers that were tabled in his name or which he initiated. A deeper understanding of Goh’s role as a major policymaker who shaped post-1965 Singapore would be possible if these very significant Cabinet memoranda were to be declassified and made available for public consultation.

In the absence of any indication that the archival records of the major policy decisions and their implementation are being made public, we are left with only the recollections of those who helped Goh draft these memoranda or who were at the receiving end of his file notes and minutes. S. Dhanabalan recalls one such memorandum that he was involved in drafting in 1960 when he was a rookie at the Singapore Industrial Promotion Board. Goh had assigned him the task of drafting the covering memorandum to seek Cabinet approval for the establishment of an “Economic Development Board”, as Goh coined it. Dhanabalan recalls:

Dhanabalan’s anecdote captures Goh’s legendary preference for short, terse and elliptical minutes and memoranda. Some of his cryptic comments in the margins of memoranda he reviewed have achieved legendary status.

From His Contributions to Economic Growth and Political Change

The public records that refer to Dr Goh are part of a larger national archive, which documents Singapore’s post-1945 and especially post-1965 development. Singapore was not expected or supposed to survive separation from the Malaysian hinterland. The fact that Singapore not only has, but even gone on to achieve global city status, has therefore become the subject of a continuing series of studies seeking to understand and explain this success. The emerging narrative explaining Singapore’s success has two themes. The first is an economic theme of modernisation and growth from a 19th-century colonial trading post to the post-industrial global city it is today. The second theme of political change and struggle has been well summarised by Goh himself: “the power struggle waged between the leaders of the People’s Action Party (PAP) and the underground Singapore City Committee of the Malayan Communist Party. The struggle began in 1954 when the PAP was captured by its United Front Organisation virtually from the day it was founded and ended in 1963 when the stranglehold was finally broken”.1 The success in achieving the latter created the political climate for the PAP to initiate its policies for economic modernisation and growth, which ultimately led to the nation’s success.

Goh’s contributions to laying the foundations of Singapore’s economic growth through prudent public finance, export-oriented industrialisation, equitable industrial relations and entrepreneurship, and human capital development have been well documented, as has the wider relevance of Singapore’s economic growth model to East Asia. The 1985 invitation he received to become an adviser to the State Council of the People’s Republic of China broadens our perception of Goh as an economic architect. The issue is how we will continue to remember or forget Goh as we review the basics of the economic foundation he laid and decide what aspects of it we can continue to expand upon, or perhaps reconstruct, for Singapore’s continuing economic growth and development in the 21st century.2

Goh’s role in Singapore’s political development will probably be remembered in the context of how he was able to envision the impact that politics could have upon Singapore’s economic development and how it should then be managed for economic growth. Unlike his colleagues, Goh did not seem as active in the vanguard of the ideological charge against colonialism or communism. He will be remembered more as the backroom strategist, planning Singapore’s long political futures to complement the economic growth he was driving. Goh’s rationale for joining Malaysia was largely, if not entirely, an economic imperative of a common market for Singapore’s economic survival. He will now be remembered as leading the initiative for separation as it became increasingly clear that a common market in Malaysia was not going to be forthcoming.

Post-1965, Goh’s role broadened to include the defence and education portfolios and he displayed his versatility as not only an economic architect, but also a social architect3 who laid the foundations of Singapore’s identity as a city-state. As in the pre-1965 era, his capacity for the lateral thinking of Singapore’s future as a city-state and its place in a tumultuous region is what many of us recall. We also remember his ability to go beyond solving the immediate problem of how to start up the armed forces or restructure the education system, instead conceiving defence as more than a military issue or understanding education as being about knowledge generation rather than rote learning.

The discussion of how we are to remember Goh as the economic and social architect of Singapore’s transformation, as a problem solver and as Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest lieutenant will continue as more information from the public records becomes available, and more importantly as we look into Singapore’s future and decide whether the policies Dr Goh put in place continue to be relevant. Goh’s speeches are also key to an understanding of what he attempted to accomplish.

From His Public Speeches

Goh’s speeches to a wide variety of audiences differ from the terse minutes and papers he drafted. As he noted, he and his PAP colleagues “may be the few remaining members of a vanishing breed of political leaders” who write their own speeches. In the preface to his first collection of speeches published in 1972,4 he lay emphasis on how “we have our ideas as to how societies should be structured and how governments should be managed. We prefer to express these ideas our way. This habit of self-expression we formed during our undergraduate days”. Goh explained that the intent of these speeches was to remind Singaporeans of “the riotous episodes of the past two decades” and to outline the challenges “we experienced in our quest for a decent living in a none too hospitable environment”, which he compared “to the biblical journeys of the children of Israel in their search for the promised land. And like Moses, [Goh and his PAP colleagues] had to explain, exhort, encourage, inform, educate, advise – and to denounce false prophets”. Goh published a second volume of his speeches in 1977.5 A third volume arranged and edited by Linda Low was published in 1995 and reprinted in 2004.6

Upon reading and rereading Goh’s speeches, one arrives at rather different conclusions about the man and his legacy. In his foreword for the 2004 reprint of The Economics of Modernization, Professor Chua Beng Huat notes that the volume “remains one of the resources I go to whenever there is a need to find out the early thoughts behind how Singapore was organised and governed”. For Chua, what is amazing in a present-day reading of the old essays is their prophetic insights. For example, Goh’s vision of China’s successful industrialisation by the 21st century and its impact on the rest of Asia, or the fundamental role of cities in the modernisation process. Wang Gungwu in the foreword to Wealth of East Asian Nations “was struck… by how the bureaucrat not only turned into a dynamic politician who tackled some daunting economic challenges but also one who could write about what was done in such a cool and scholarly manner”. Dr Linda Low concurs that Dr Goh “always tries to be informative [in his speeches], and takes the time to provide the background before he rallies round to his chosen theme. Such overviews, although highly intellectual and analytical, are easily digestible and understood”. Low speculates that there is in Goh “an instinctive urge… to teach and inform, never really given the presence to blossom, [which] surges to the fore and makes its presence felt in his speeches”. She observes that Goh’s speeches are a world apart from his succinct and elliptical notes and memoranda in the classified records. Through his speeches we glean a rather different impression and understanding of Goh and his legacy. Rereading Goh’s speeches may give us new insights into how we want to remember him in the future.

How Goh Wished To Be Remembered

Another set of memories of Goh – of how he wished to be remembered – emerges from his speeches and interviews. His choice of speeches worthy of reprint and the titles of the two volumes of his speeches provide an insight into how Goh viewed himself and perhaps what he wanted to be remembered for. In the preface to the second collection of his essays, Goh reiterated the metaphor of Moses: “Singapore’s political leaders had often to assume the role of Moses when he led the children of Israel through the wilderness in search of the Promised Land. We had to exhort the faithful, encourage the fainthearted and censure the ungodly.”

Another recurring theme in Goh’s speeches is their accentuation on practice and disavowal of theory. Towards this end, Goh titled his second collection of essays The Practice of Economic Growth to emphasise this stand. However, he appears slightly apologetic when he then goes on to write that he has “delved more deeply into theory in chapter 7 (of Some Unsolved Problems of Economic Growth) than a practitioner should, the object of the exercise was to assess how far theory conforms with practice in the real world”. Clearly, Goh wanted to be remembered as a practitioner and not a theoretician. But that raises the question of what it was that ultimately motivated Goh’s practice? It was clearly not the mundane political issues of the day which drive most other politicians and Goh was scornful of ideological commitment to any form of socialism.

Ironically, Goh’s practice was actually driven by theory. “The practitioner”, he declared, “uses economic theory only to the extent that he finds it useful in comprehending the problem at hand, so that practical courses of action will emerge which can be evaluated not merely in narrow economic cost-benefit terms but by taking into account a wider range of considerations.” Thus not only chapter 7 of Goh’s The Practice of Economic Growth is concerned with economic theory, but a large number of other essays refer to Max Weber, Joseph Schumpeter or Peter Bauer at the expense of Keynesian economic theory. Goh’s preference of seeing the world through the spectacles of economic theory has its beginnings at the London School of Economics. In 1956, he had submitted a highly technical analysis of the problematic nature of estimating national income in underdeveloped countries, with Malaya as a case study, for his doctorate degree. Perhaps this adds to our paradoxical memory of Goh – a practitioner driven not by politics or ideology, but by theory.

How are practitioners to be judged? In Goh’s own words, “a practitioner is not [like the theoretician] judged by the rigour of his logic or by he elegance of his presentation. He is judged by results”. By 1972, “Singaporeans knew that they could make the grade. While we had not reached the mythical Promised Land, we had not only survived our misfortunes but became stronger and wiser in the process. As a result we came to believe we understood the formula for success, at least in the field of economic growth.”

Dr Goh and his colleagues’ response to separation as a Kuala Lumpur initiative gives us a glimpse of the politician as a successful practitioner. In an oral history interview with Melanie Chew for her large-format book Leaders of Singapore,7 Goh revealed a rather different recollection of the events leading up to separation. This portion of the transcript merits quotation:

“Melanie Chew: When did you feel that Malaysia was going to break up? Was it a surprise to you?

Dr Goh: Now I am going to let you into what has been a state secret up to now. This is a file, which I call Albatross. In the early days there were a lot of discussions about changing the terms of Malaysia by the Prime Minister, Rajaratnam, and Toh Chin Chye. It got nowhere. They discussed all types of projects. Was Singapore to be part of Malaysia, but with special powers, or with no connection with Malaysia? Now on the 20th of July 1965, I met Tun Razak and Dr Ismail. Now this is the 20th July 1965. I persuaded him that the only way out was for Singapore to secede, completely. (reading) “It should be done quickly, and before we get more involved in the Solidarity Convention.” As you know, Rajaratnam and Toh Chin Chye were involved in the Solidarity Convention. Malaysia for the Malaysians, that was the cry, right?

Melanie Chew: This Solidarity Convention, you felt, would be very dangerous?

Dr Goh: No, not dangerous. I said, “You want to get Singapore out, and it must be done very quickly. And very quietly, and presented as a fait accompli.” It must be kept away from the British. The British had their own policy. They wanted us to be inside Malaysia. And, they would have never agreed to Singapore leaving Malaysia. Now, the details, I won’t discuss with you.

Melanie Chew: How did Tun Razak and Dr Ismail react?

Dr Goh: Oh, they themselves were in agreement with the idea. In fact, they had themselves come to the conclusion that Singapore must get out. The question was, how to get Singapore out?

Melanie Chew: So the secession of Singapore was well planned by you and Tun Razak! It was not foisted on Singapore!

Dr Goh: No, it was not. (There followed a long silence during which he slowly leafed through the secret file, Albatross. Then he shut the file, and resumed his narrative.) Now then, independence. The first thing an independent state must have is a defence

force…”

We can speculate as to why Goh chose to reveal this in 1996. Was it that in 1996, when Singapore was taxiing towards economic take-off to global-city status, it could finally be revealed that separation was a blessing in disguise?

From the Personal Recollections of His Peers

The Oral History Centre that Dr Goh was instrumental in establishing in 1979 has been systematically interviewing the political cast of characters, both PAP and non-PAP, for their memories of the political struggles in the 1950s. Not everyone who was invited by the Oral History Centre has responded positively. This is because of the subjectivity of the interview process in allowing the interviewee to determine the extent to which he would like to reveal his memories to a network of family, friends, associates and others in order to establish an archival record for posterity. Restated, the issue is not whether the interviewee is able to remember a person, but rather an ethical issue of whether the interviewee wants to remember that person and, if so, in what form.8

Goh, Toh Chin Chye and Lee Kuan Yew have complex shared memories going back to their student days in London and of the formation of the Malayan Forum, of which Tun Razak, among others, was also a member. Understanding these shared memories is critical to understanding the “journey into nationhood” on which these men were leading Singapore. Goh’s PAP colleagues and staff who helped him run the Kreta Ayer Constituency and the numerous civil servants who worked under him all have complex memories associated with him. To get them to reveal these shared memories in formal oral history interviews, one assumes that each of these individuals has an inherent confidence in the relationship and its ability to withstand an ethical decision to divulge one’s true sentiments about one another and Goh. Alternatively, one may suppose that such relationships have, over the years, become more distant and so revealing shared memories of these relationships is less of an ethical dilemma today.

This, then, is the challenge of recording oral history as narrated by Dr Goh’s colleagues and staff.

Conclusion

Remembering Goh is not an objective task of merely compiling sources from the different categories in order to derive a composite portrayal of Goh that is comprehensive and, as far as possible, true. Rather, it is a complex process in which the different sources interact with and impact each other. Our remembrance of Goh’s contributions to the making of the “Singapore Story” may evolve and change if and when the official public records are opened. Our personal memories of Goh are probably the most problematic. On the one hand, they are the remembrances that are most likely to change over time and become embellished with other memories and evidence with each recounting. On the other hand, they are of greater significance in helping us to gain an understanding of the finer nuances of a complex public personality than is contained within both the official public records and in Goh’s own recorded perceptions of himself.

For a selection of literature on Goh Keng Swee, have a look at our Collection Highlights article, “Living Legacy: A Brief Survey of Literature”.

Head of External Programmes

S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies

Nanyang Technological University

NOTES

-

Goh, in his justification for the establishment of an Oral History Centre to interview and record personal accounts of this “largely unrecorded” fight between the PAP and the communists, quoted in Kwa Chong Guan, “Desultory Reflections on the Oral History Centre at Twenty-Five,” in Reflections and Interpretations, ed. Daniel Chew and Fiona Hu (Singapore: Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, National Heritage Board, 2005), 6–7. (Call no. RSING 907.2 REF) ↩

-

For the outline of the issues and challenges, see: Gavin Peebles and Peter Wilson, Economic Growth and Development in Singapore: Past and Future (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2002). (Call no. RSING 338.95957 PEE) ↩

-

Kwok Kian-Woon, “The Social Architect: Goh Keng Swee,” in Lam and Tan, eds., Lee’s Lieutenants, ed. Lam Peng Er and Kevin Y.L. Tan (St Leonards, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 1999), 45–69. (Call no. RSING 320.95957 LEE) ↩

-

Goh Keng Swee, The Economics of Modernization (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish 2004; Reprint of 1972 edition), xi. (Call no. RSING 330.95957 GOH) ↩

-

Goh Keng Swee, The Practice of Economic Growth (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic, 2004; Reprint of 1977 edition). (Call no. RSING 330.95957 GOH) ↩

-

Goh Keng Swee, Wealth of East Asian Nations (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic, 2004). (Call no. RSING 330.95957 GOH) ↩

-

Melanie Chew, Leaders of Singapore (Singapore: Resource Press, 1996). (Call no. RSING q920.05957 CHE). The book is a series of 38 life histories of persons Chew considers to have led Singapore in the post-1945 years. Most of the life histories are reflected as transcripts of oral history interviews with the leaders themselves, except for four early leaders who had passed on. As such, their life histories were reconstructed from interviews with those who knew them. ↩

-

In this context, what we are reading in Chew’s transcript of her interview with Goh is not Goh’s inability to recall what happened in the weeks leading up to 9 August 1965, but a sieving and shifting of his memories to make moral choices and political judgments of what he believes should be revealed for a revision of Singapore’s history. Lee Kuan Yew in his memoirs and funeral oration for Goh also recalls that he, Goh and Tun Razak were key actors in the move to separate Singapore from Malaysia. In doing this, Lee is also reshaping and reworking his memories from his present vantage point. The oral history interview is therefore not a passive retrieval of information from the interviewee’s memory, but an active process of challenging the interviewee to review, and if necessary, reconfigure his memories of his past from the vantage point of his present. ↩