Early Tourist Guidebooks: Willis’ Singapore Guide (1936)

Senior Librarian Bonny Tan examines the Willis’ Singapore Guide, an early tourist guidebook available at the National Library.

— Willis (1936, p. 83)

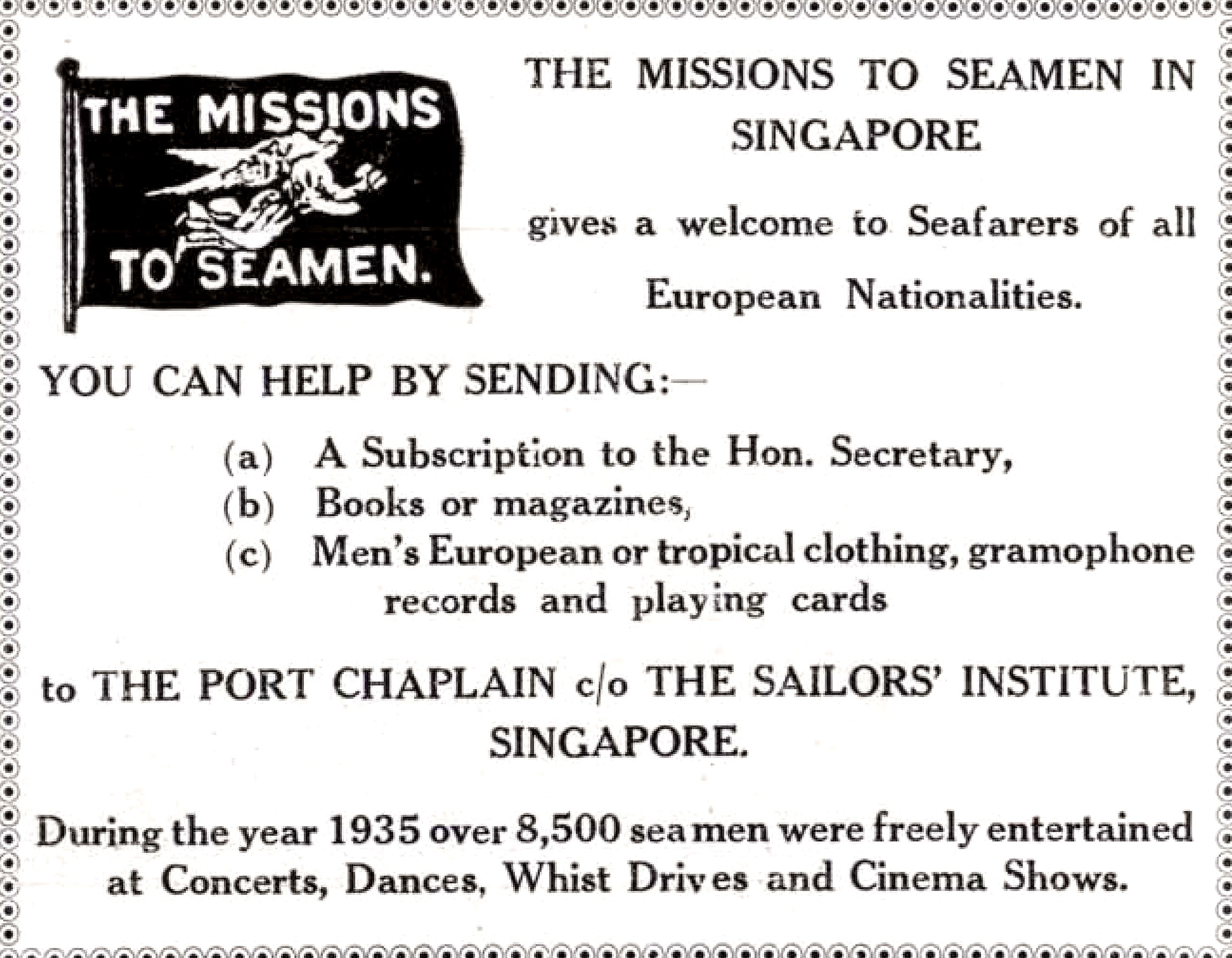

First published in April 1934, Willis’ Singapore Guide1 seemed to fly off the printing press, running into three editions within the first year of its publication.2 By its sixth edition in 1936, it had colour illustrations and was printed on art paper.3 Its cost invariably increased from 40 cents to a dollar. Each subsequent edition offered new insights into Singapore and its way of life. The fact that it was being distributed for free to visiting merchant ships by the chaplains for The Missions to Seamen certainly helped boost its circulation. A newspaper article promised that this budget guide to Singapore will introduce the “stranger to the city… what to see, where to go, and what is more, the cheapest way to do it”.4 Certainly, its tips for budget stays, cheap travel outside Singapore and local eats made it “the answer to the tourist’s desire for finding his way around town”.5 Unlike other turn-of-the-century guides that were often targeted at the wealthy traveller, Willis’ Singapore Guide was written especially for the well travelled but less well-to-do sailors to the East.

The Sailor’s Welfare: The Missions to Seamen

In the 1930s, Singapore was already considered one of the world’s largest ports with its role primarily as a clearing station. It served as an important coaling centre with nearly all of its coal used to fuel visiting ships (Willis, 1936, p. 79). Despite the large number of sailors passing through Singapore on various merchant ships, the welfare of seamen was not always a priority.

In 1926, The Missions to Seamen6 also known as Flying Angel was established in Singapore, headed by Rev. G.G. Elliot. It sought to become a home away from home for these itinerant seamen, providing everything from a roof over one’s head and a warm meal, to attending to stranded, ill or distressed sailors. John Ashley, an Anglican priest, founded the movement in 1837. When he was holidaying off Bristol, Ashley’s child inquired as to who ministered to the islanders across the Bristol Channel. The question led the priest to minister to the fishermen on the island and, subsequently, to the sailors on passing ships. In 1858, an Anglican entity named The Missions to Seamen was set up through an amalgamation of various ministries to seamen in Britain. Within six months, a request was made by concerned residents in Singapore for a Chaplain to minister to the spiritual needs of passing sailors.7 Although there were various forms of institutions and groups that served these sailors across several decades, it was more than half a century later, in 1926, when a monetary gift from a pilot’s widow for a Chaplain’s salary enabled The Missions to Seamen to take formal shape here.8

By 1935, 10,245 sailors had visited The Missions to Seamen.9 This was because the visits The Missions made to ships totalled 1,310, displaying a more than three-fold increase against 1927 when only 391 ships were visited.10 Initially, in 1927, attendance for entertainment was 1,500, but the numbers had risen to 10,245 in 1935, portraying close to a ten-fold increase.11 In 1932, despite the world’s trade being “at a phenomenally low level”, the chaplain still visited 800 vessels that year.12

Located at the famed Sailors Institute at Connell House along Anson Road for several decades, The Missions’ facilities in the 1930s included a restaurant, a cinema and even a milk bar.13 By 1947, it had a dance floor, a reading room, a library and tennis courts. The restaurant served between 7,000 to 10,000 meals a month with a full meal priced at a humble $1.14 Its hostel could initially accommodate 34 officers and 64 seamen, many of whom were awaiting transfers to other ships assigned to them. The hostel was so popular that by 1938, the Sailors’ Institute was known as the Marine Hostel.15 It was the activities and services that the Marine Hostel offered that kept drawing the sailors back to this, their second home. The recreational activities included not only standard games such as billiards, table tennis, draughts, darts and chess but also other activities which Rev A.V. Wardle summarises succinctly: “At the Marine Hostel officers and men could obtain board and lodging, get good meals at moderate prices, play games and write letters, attend whist drives and dances, where they meet women of their own nationality, see talkie cinema shows at least twice weekly, attend Sunday concerts where they very often hear the best talent in Singapore, and, perhaps best of all, they are certain of a warm welcome, without which bricks and mortar mean so little.”16

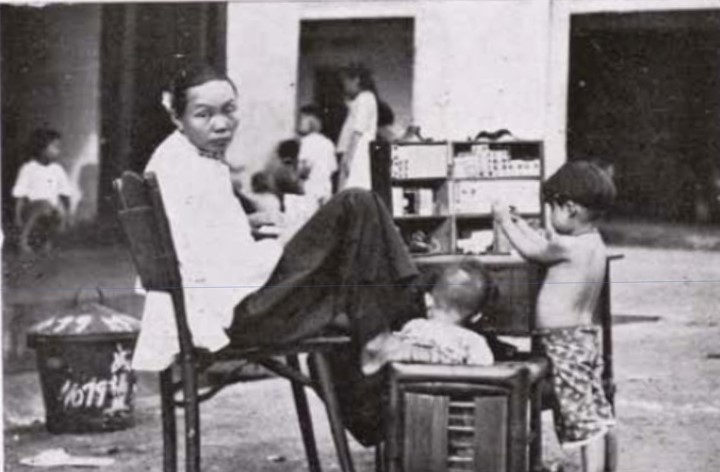

The Marine Hostel’s Steward: A.C. Willis

A.C. Willis was a key anchor to this “warm welcome” in his position as Steward of the Marine Hostel and later as Assistant Superintendent. He left his personal stamp on these activities, having served at the Marine Hostel for 21 years until his death in 1951. Willis’ success in entertaining the sailors was partly on account of his close identification with the needs of the sailors who visited the hostel as he had worked for more than 14 years previously with the Blue Funnel, rising to the rank of Quartermaster. “We aim to do all we can to make a man feel that this is his home while he is in port and it gives me great pleasure to do what I can for them, being an old sailor myself.”17

Under his able and fun-loving leadership, there was a “glut of games”18 amongst visiting seamen. Football proved especially popular with ships wiring messages prior to their arrival so they could be entered into a match.19 He also loved his food and had prepared 75 pounds of Christmas pudding for around 300 sailors in 1949, the most Christmas pudding prepared in postwar Singapore then.20 His only other known publication besides the Guide is a book of menus.21

Since Willis began work at the Marine Hostel in 1929, he had taken sailors around for tours of the city and beyond Singapore’s boundaries.22 At Johor they would visit pineapple farms, the Gunong Pulai waterfalls and Pontian Kechil reservoir.23 In the 1930s, sometimes as many as a few hundred sailors would take the tour organised by the Seamen’s Institute.24 For example, in 1936, Willis took 700 American sailors from the United States Asiatic Fleet on tour through Singapore and beyond to Johor, Kota Tinggi and Pelepah Valley.25 Even as late as 1941, he accompanied sailors to Kota Tinggi where enroute, they stopped by pineapple plantations and rubber factories as well as tin mines.26 Willis’ passion and keen interest in travelling around Singapore and the Malay Peninsula gave shape to the Guide which he published on his own account.

A Sailor’s Insight

The guide begins with a brief historical prelude and proceeds to focus on the nuts and bolts of travel through Singapore and Malaya. Besides presenting tedious but essential details for the traveller, such as exchange rates and bank locations, Willis offers details that are unique to the era and to the appetite of a sailor. It was, after all, written with the visiting seaman in mind, presenting the city to his interests and for his budget.

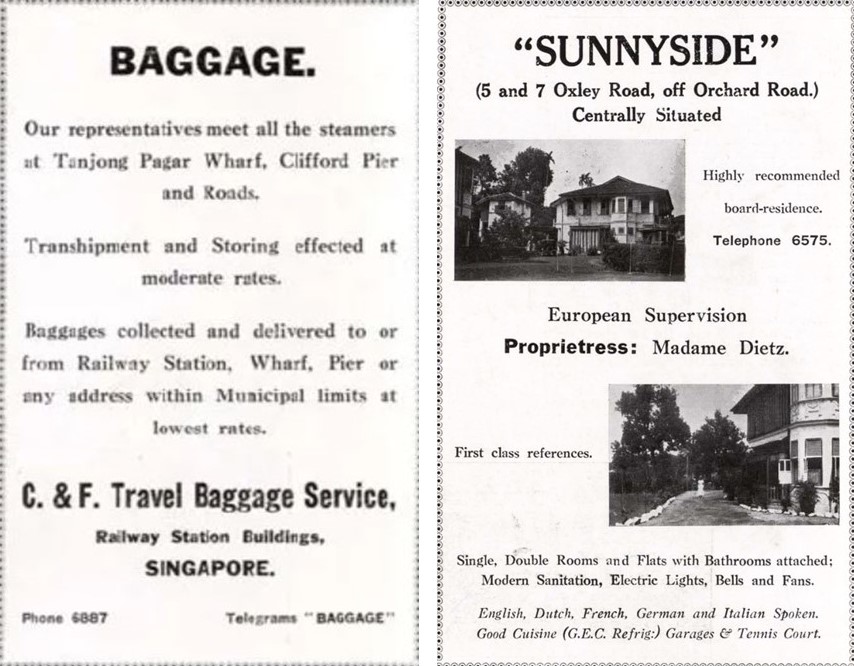

For example, he highlights the services provided and the role of the authorities that initially board the ship upon berthing. The police are the first to enter and inspect passports. They are followed by Indian money changers whom Willis suggests give better rates than those on shore. Then come hotel runners and baggage porters who offer to take one’s luggage safely to one’s preferred residence or hotel for a charge of merely 10 cents for each piece of luggage carried off the ship and an added 10 cents to accompany it to its destination.

Again, with deference to the seaman’s perspective and budget, besides a listing of well-known hotels, the guide also recommends several boarding houses like Sunnyside on Oxley Road, Whitehall on Cairnhill Road and Morningside on River Valley. Advertisements of these quaint boarding houses are accompanied by photographs and further details of their proprietors and the services they provide.

A Taste of Local Cuisine

Woven through his descriptions of places, Willis, ever the connoisseur of local cuisine, often mentions an eatery, its recommended house dishes and the restaurant’s unique ambience. Raffles Place, John Little and Robinson’s were the main shopping haunts but Willis cannot resist noting that “[at] each is a comfortable lounge café, where one may indulge in tea, coffee, ices, alcoholic and other drinks in cool and restful ease. They also supply luncheons and light refreshments” (Willis, 1936, p. 85). Even describing the shops along Battery Road, Willis slips in a note on “G. H.” Café, “an excellent place at which to get your luncheon and have that ‘one for the road’ before returning to the ship” (Willis, 1936, p. 91).

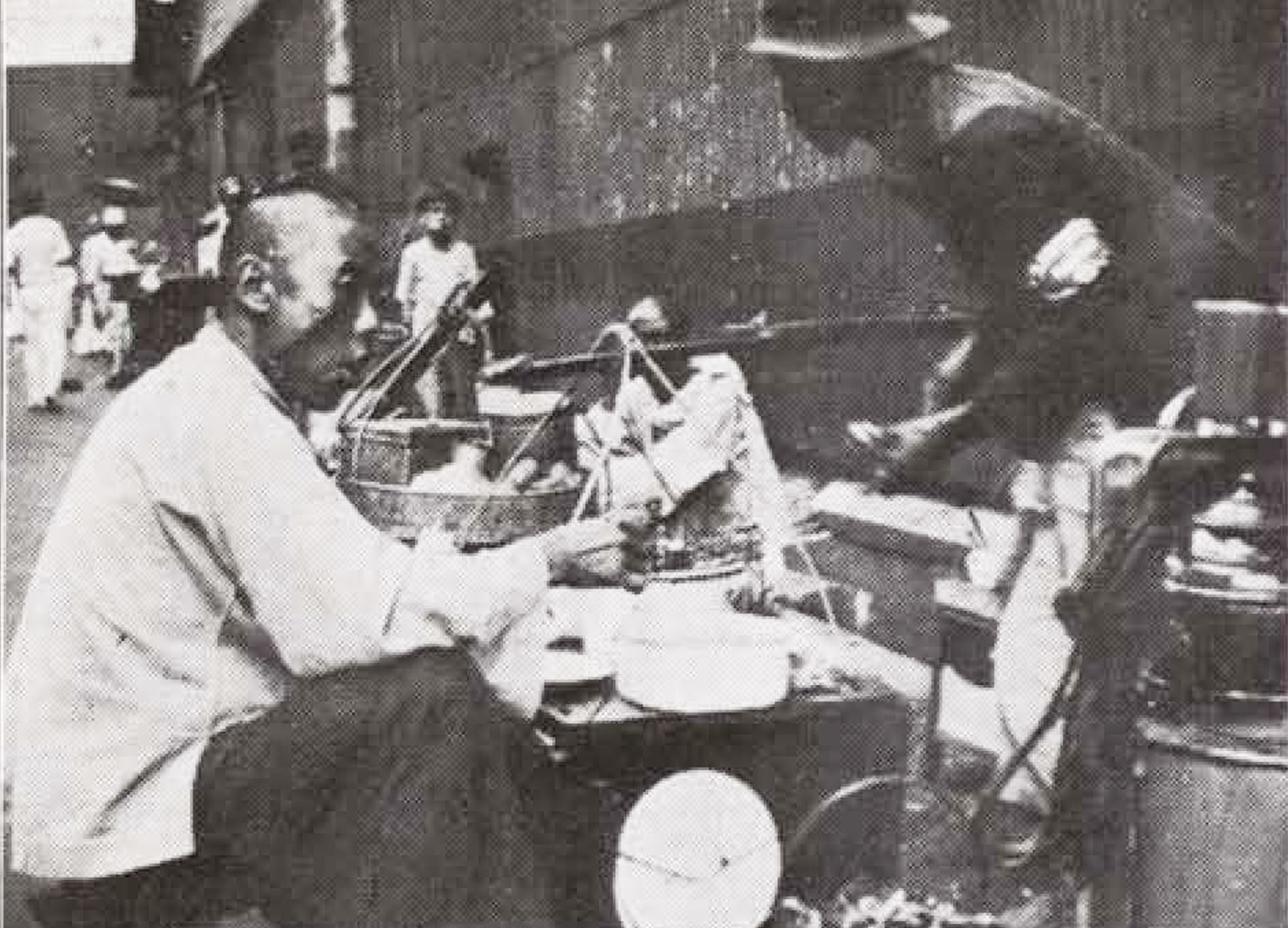

Local food is also highlighted as he recommends the Oi Mee hotel for its good Chinese dinner (Willis, 1936, p. 40). An entire chapter is dedicated to the Satai (Satay) Club, located along Beach Road between the Singapore Drill Hall and the Marlborough Picture Theatre (Shaw Towers). That it is mentioned in Willis’ 1936 guide quashes the commonly held belief that the Beach Road Satay Club was set up in postwar Singapore. This assumption may have arisen when the club relocated to Dhoby Ghaut in the 1950s because of frequent accidents occurring at the nearby Tay Koh Yat Bus Co terminus but poor business at that location led the Satay Club to return to Hai How Road (no longer in existence) where it had originally begun.27

Satay was already a popular snack, offered by itinerant vendors.28 Willis suggests that the term “satae” and the snack itself are of Chinese origin, the term believed to mean “three pieces of meat” in a Chinese dialect (Willis, 1936, p. 145), although at the Satay Club it is mainly Malays who whip up this dish from a simple wooden box. The box carries the ingredients for the dish – sticks of partly cooked chicken, beef or mutton which are then grilled over a charcoal fire. An unending round of satay is dished out until the patron asks to stop. The top of the box is used as a tray with three stools strewn around it. Spicy sauce and a relish with onions accompany the barbecued sticks of meat. Willis gives details of how satay is popularly consumed by westerners in these humble circumstances. “After the cinema or when hotels are closed, it is not an uncommon sight to see European ladies and gentlemen in evening dress sitting around these ‘Satai’ stalls on the open road” (Willis, 1936, p. 147). “When you have finished eating, the Malay [cook] will collect the sticks which have been used, and charge you two cents for each. And when I tell you that I have known people to eat as many as forty, and even sixty sticks of Satai’ – and that’s a good pound of meat – at one sitting, you will understand that the dish is a popular one amongst Europeans, as well as others” (Willis, 1936, p. 148).

(Right) Borneo Motors' advertisement on the Austin Seven (Willis, 1936, p. 119).

Negotiating Traffic

Describing the type of vehicles in Singapore, Willis keenly observes: “there are still features in [the traffic] which distinguish us from cities such as Tokio [sic] (where the rickshaw has practically been abolished, but where the bicycle seems to do what it likes), and Peking (where the rickshaw still reigns supreme). We have not got a problem which worries Shanghai – the hand-cart menace. Neither have we much slow-moving traffic drawn by horses or bullocks. There is, however, much to look at besides motor traffic: yet in a few years all our slow-moving traffic will have gone. We shall have become like any other great modern city” (Willis, 1936, p. 110).

Unlike the orderly, controlled traffic of today, vehicles in Singapore of the 1930s wended their way through streets according to their own laws. In “places where there is no traffic control at all [y]ou will then appreciate the subtlety and the traffic sense of the Singapore driver. He seems to know instinctively what the rickshaw in front is going to do: he also knows that the wobbling fellow on the bicycle – though on the wrong side of the road – will not attempt to get on the correct side until after you have gone past. One will often think that one is going to be involved in a smash, but no smash has resulted because one’s driver and the other fellow seemed to know by instinct exactly what to do” (Willis, 1936, pp. 111–112).

Traffic was controlled manually and it was a hot and difficult task. Willis considers how the traffic constables coped: “You may see a bicycle laden with drinking water and the constables being refreshed there from, and you will approve of this kind thought on the part of the authorities, as one can well imagine what it must be like to stand for an hour or two in the heat of the day with motor cars dashing past one within an inch or so of one’s body” (Willis, 1936, p. 113).

Singapore Tours and Sights

“A large number of people complain when they go ashore, that Singapore is an expensive place to go round. That is not altogether true; every port of the world is expensive to move about in, especially if it should happen to be your first visit” (Willis, 1936, p. 39).

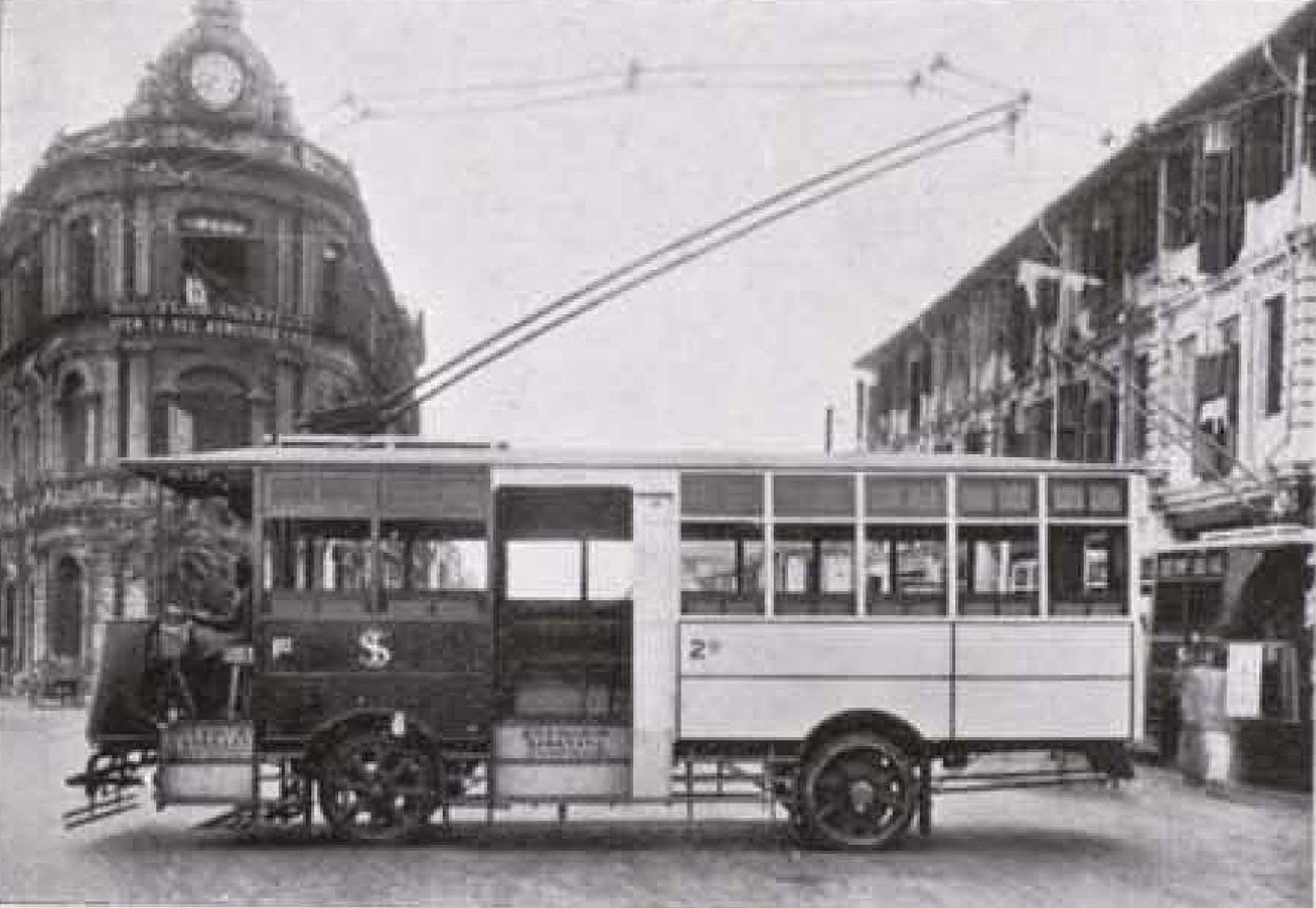

In keeping with the budgetary needs of his fellow sailors, Willis advises against the norm of travelling by rental cars and taxis and instead suggests travel by trolley buses as “the cheapest way to travel about” (Willis, 1936, p. 39). Besides tramcars, Willis also believes a rickshaw ride gives a good perspective to street life in Singapore although this does not beat the advantages of walking around the city.

For the seamen keen on experiencing “a cheap, comfortable, and very convenient way of seeing a good part of the City” (Willis, 1936, p. 93), Willis promotes the tram route for No. 1 Trolleybus. The journey begins at Keppel Harbour and continues along the main line of the harbour, passing through the railway station, the Tanjong Pagar Police Station, key commercial offices such as that of F&N and Tiger Beer, and the all-important Sailors’ Institute at Anson Road for these seamen tourists, before it heads down Collyer Quay past banks and offices through the Anderson Bridge past the Victoria Memorial Hall to River Valley Road. Willis draws the tourist’s attention to the location of what once was the Singapore Railway Goods Terminus “long since dismantled and beyond the memory of most people. It is interesting to note that this valuable plot of land is being considered as a site for the proposed Aquarium” (Willis, 1936, p. 105). This was possibly the seed of an idea which would later become the Van Cleef Aquarium. Passing by the Tank Road Hindu Temple, which Willis calls the Chettiar Temple, he describes the “gruesome” spectacle of the annual Thaipusam in some detail, with the main attraction being a “man who trails a car behind him attached to his body by cords, on the end of which are hooks piercing the flesh” (Willis, 1936, p. 105).

Once past the Hindu Temple, Willis recommends leaving the tram car and taking a walking tour instead, past Government House and down Orchard Road. He offers few details, such as the reasonably priced yet excellent meals served at Capitol Theatre and the music shop run by D’Souza Bros, near the Adelphi Hotel, where one can find everything from gramophone records to musical instruments and even a Gents Outfitting Department (Willis, 1936, p. 107). At North Bridge Road, Willis points out Yamada and Company, a Japanese curio shop and Jhamatmal Gubamall, a popular silk shop, although High Street boasts a string of highly recommended silk shops too. High Street also offers a good stationery shop, Mohd. Dulfakirs Stationers Shop with an excellent stock of papers and periodicals from England and America. Shahab and Co has great reptile skins while Singapore Photo Co. attends to the photographic needs of the tourist. Café de Luxe, both well-decorated and welllocated, is the final rest point before hopping back onto tram car No. 1 to one’s ship.

Besides this detailed tour through the town of Singapore, Willis also points to selected sites and how best to benefit from visiting them. They include the then familiar but now long forgotten locations of the 1930s such as amusement parks and Singapore’s Petticoat Lane (officially known as Change Alley). He also makes mention of locations such as the Gap Road House, swimming schedules for Mount Emily Swimming Pool, and details of the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station.

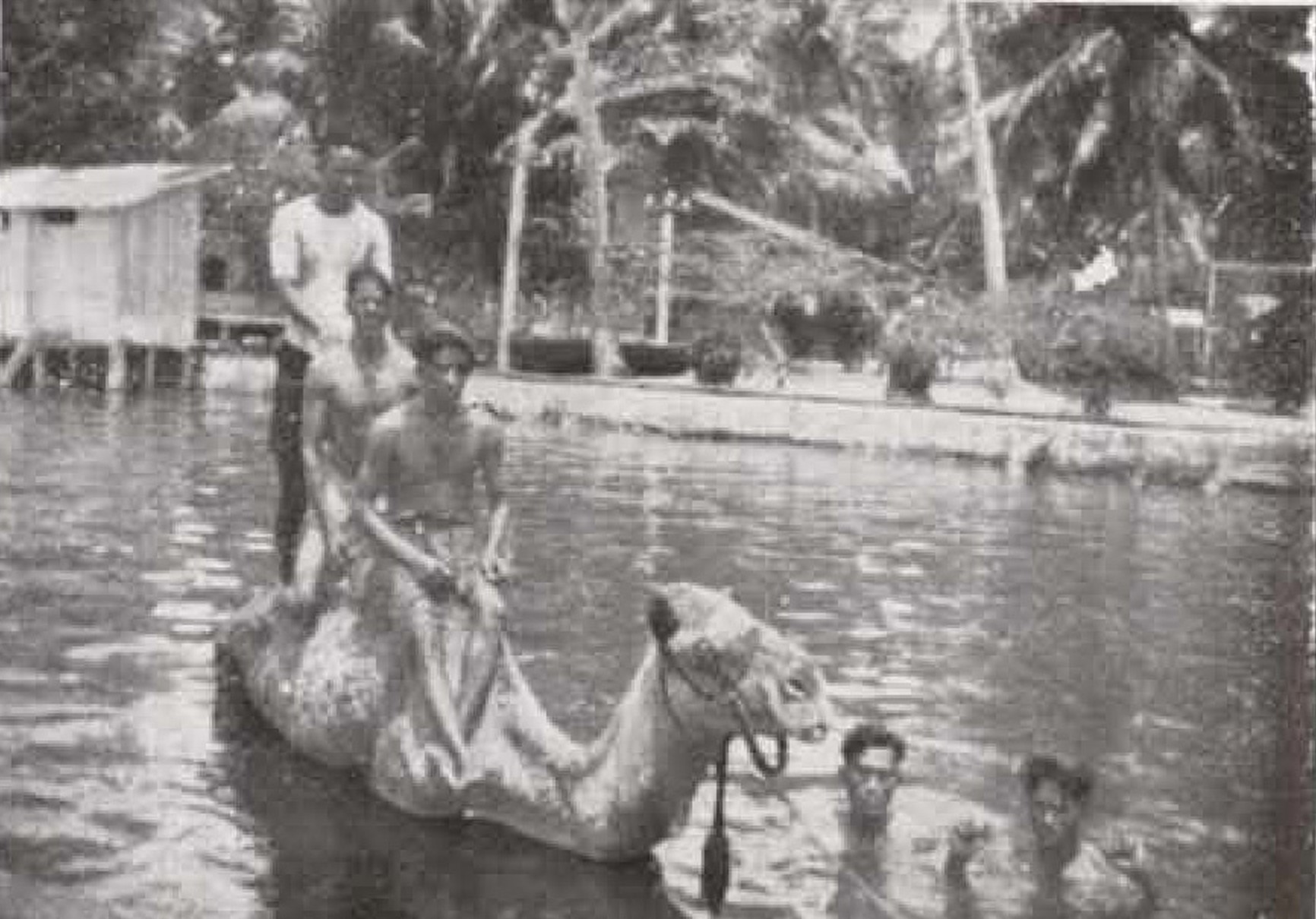

Most interesting is his description of the Ponggol Zoo, also known as the Singapore Zoo, a predecessor of Singapore’s famed zoo today. Interestingly, Willis had noted in a description of the Botanical Gardens that there had been animals kept at the Gardens since 1875 but this was discontinued in 1905 largely through lack of funds (Willis, 1936, p. 115). The Ponggol Zoo was started in 1928 by a Malayan, W.L.S. Basapah primarily as a holding bay for animals he had bought off trappers to sell to major animal dealers around the world.29 Thus, “the Malayan animals collected here are still in their primitive state, and not so tame as the ones… in the Zoos [overseas]” (Willis, 1936, p. 119). In fact, much of the description of the Ponggol Zoo in the guide focuses on techniques in trapping Malayan tigers using a dog as bait.

“[The Malay trapper] has a coffin like arrangement which is made of bamboo, strung together. The dog is placed at one end, and the coffin is tilted; along comes Mr. Tiger, and tries to get at the dog; immediately he is inside the trap, it falls on him, and he is not able to get out. The falling of the trap releases the dog, which escapes to its home. The trappers then know they have a capture. This method is not always a success so far as the dog is concerned; should the Tiger arrive with any of his friends, the dog will have very little chance of getting away” (Willis, 1936, p. 120).

During the late 1930s, the zoo rapidly increased in size and variety of animals, with animal exchanges made with zoos from Australia, the Americas and other key zoos worldwide. The animals included roaring lions, barking seals and purring panthers and covered various kinds of birds, mammals and reptiles. The private enterprise thus transformed the muddy area of Ponggol, which was overgrown by bushes, into well-laid-out manicured gardens with a menagerie of caged animals. The zoo was a popular venue for families and visitors alike and Willis often brought his sailors on tour for a mandatory stop here. Between 1940 and 1941, The Straits Times published Barbara Murray’s Winkleday Adventures, a series of imaginative animal stories set in the Ponggol Zoo.

Industries and Inventions

Besides giving a geographical overview of Singapore city, Willis’ guide also conveyed key aspects of industries that drove the Malayan economy such as rubber and other agricultural industries like rattan and pineapple canning which his tours included. There is a specific chapter titled Industries where Willis highlights unique trades and local inventions such as Solo-air.

Created by E.H. Hindmarsh, a British resident in Singapore working for the furnishing company Structures Ltd., Solo-air was reputed to cool down rooms through an innovative system of ventilation. Turning warm air into cold air, the technology was cleverly built into furnishings that emanated cool air via ducts. Thus, “instead of the fixtures tending to disfigure the beauty of interior decoration they actually contribute towards it; being set in such attractive things as flower bowls, ash stands, electric lamp shades of artistic design which can all be placed according to ones’ own wish on chairs, tables, or writing desk” (Willis, 1936, p. 73). “It is 100 per cent British and a great deal of the work is done locally” (Willis, 1936, p. 73), which meant that much of the furniture created to house the system was undertaken by Singapore craftsmen and the outcome proved comparable to what was produced in England.

As a form of air-conditioning, the invention was expected to replace fans. Several homes of wealthy Europeans were fitted with the system within a year along with established institutions such as in the new Kelly and Walsh building at Raffles Place in 193530 and the Chief Justice’s office in 1939. In the court, jets of air were directed at the feet of the judges and barristers while each juror had his own nozzle, which he could adjust at his convenience.

Not Just a Local Guide

The guide goes beyond describing Singapore and leads the visitor across the causeway for more sights and adventures. To head further north, Willis advises, “Hire a taxi, and say ‘Johore’ to the driver and he will proceed there straight away” (Willis, 1936, p. 47). Besides Singapore, both Johor and Melaka are also analysed. Willis outlines not only the sights to behold in both these towns but also their historical legacy stretching back to the days before colonialism left its mark.

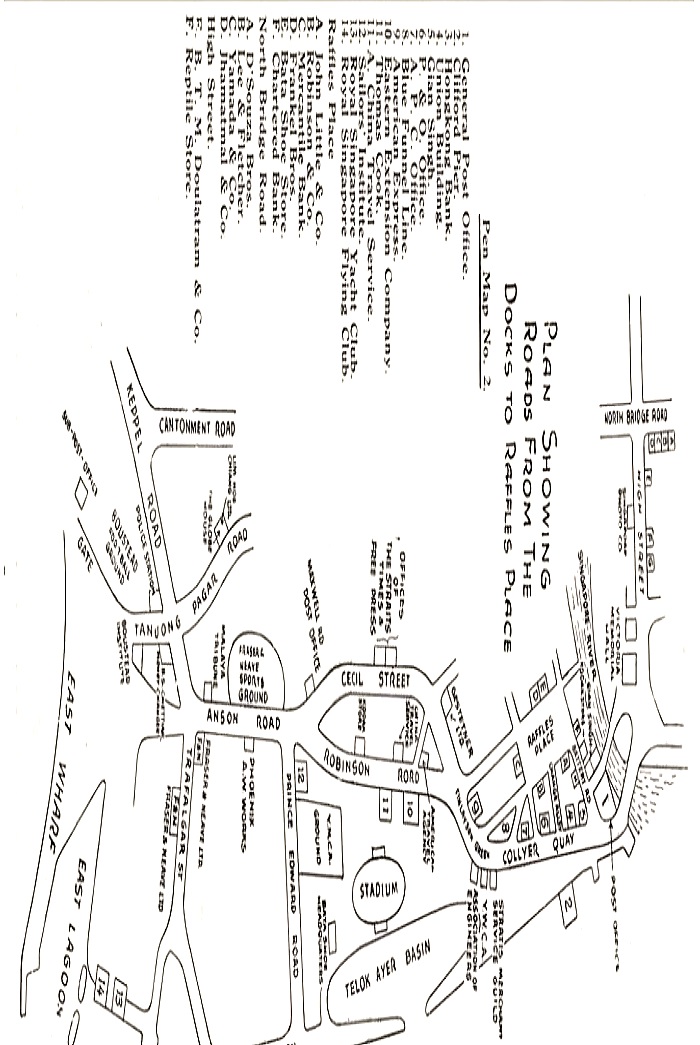

The guide is not merely a textual description of sights but also a visual feast of life in Malaya in the 1930s, particularly through its maps, photographs and advertisements. Willis most likely made the sketch maps of tours through the city centre. There are four sketch maps inside entitled “Singapore Docks” covering mainly Keppel Harbour, “Plan showing roads from the docks to Raffles Place”, “Raffles Place” and “Shopping map” stretching from Beach Road to the beginnings of Orchard Road. They locate buildings, shops, businesses, tourist spots and places of leisure on a grid map with familiar street names helping the modern reader imagine where these buildings once stood. He also introduces sites that would possibly be of interest to the seamen, such as the Blue Funnel Club at Cantonment Road, the China and American travel services along Robinson Road and even the Kodak store located there. Willis’ passion for football is evident from the various football fields around the city-centre that are highlighted.

The publication also has photographs of places and peoples, capturing images of tradesmen, village and town life, and classical buildings now demolished. Although Willis does offer a standard acknowledgement, no credit is given for the photography and individual photographers are unknown. However, his concluding page indicates that the photographs can be purchased from two Japanese companies – Nakajima & Co. and Kawa Studios. The photographs demonstrate the keen eye that these Japanese had for prewar Singapore. For illustrations, the guide proves to be a treasured showcase of merchandise, businesses and shops in prewar Singapore. Interestingly, advertisements often mirrored Willis’ text where a shop, service or invention he writes about has a parallel advertising poster printed on the next page. The guide also has an index of these business advertisements for easy reference. These may have been a clever marketing ploy Willis engaged in in order to self-publish the guide. Nevertheless, it makes the guide the perfect time capsule for an insight to businesses catering to the visitor in the 1930s. Shopfronts, long gone, have details of their services, proprietors and opening hours emblazoned in their advertisements. Long standing institutions and businesses such as John Little, Haig whisky and MPH portray art noveau perspectives of themselves in the 1930s.

The guide continued to be published after the war with as many as 5,000 copies published in 1949.31 By the time Willis passed away in early 1951, he was known as “a good friend of merchant seamen passing through Singapore”.32 His legacy remains his Guide, which continues to speak to many travellers, both seamen of the past as well as today’s curious time travellers. The guide is part of the Rare Book Collection and can be accessed online on Singapore Pages at http://sgebooks. nl.sg/details/020000657.html

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Ernest C.T. Chew, Visiting Professorial Fellow, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, in reviewing this article.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

A. C. Willis, Willis’s Singapore Guide (Singapore: Alfred Charles Willis., 1936). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.57 WIL)

“A New Guide,” Straits Times, 30 May 1934, 13. (From NewspaperSG)

“Air for Judge, Jury, Barristers,” Straits Times, 2 August 1939, 4. (From NewspaperSG)

Clergyman’s Tribute to Singapore, Straits Budget, 8 February 1934, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

“Dangers Faced by Men of Merchant Navy,” Straits Times, 21 June 1941, 11. (From NewspaperSG)

“Dutch Sailors See Singapore,” Straits Times, 20 June 1940, 12. (From NewspaperSG)

“Furnishings Set High Standard,” Straits Times, 2 August 1939, 4. (From NewspaperSG)

“Helping Seamen in Singapore,” Straits Times, 11 May 1933, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

“Housing Conditions in the S. S.,” Straits Times, 27 August 1936, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

“Impressive New Building,” Straits Times, 5 September 1935, 15. (From NewspaperSG)

Mervyn E. Moore, Eighty Years: Caring for Seafarers: The Singapore Branch of The Mission to Seafarers (Singapore: Singapore Branch of The Mission to Seafarers, 2006). (Call no. RSING 266.35957 MOO)

“Missions to Seamen in Singapore,” Straits Times, 21 April 1936, 12. (From NewspaperSG)

“Notes of the Day – The Ponggol Zoo,” Straits Times, 18 January 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

“Notes of the Day – Willis’s Guide,” Straits Times, 17 January 1936, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

“Seamen’s Hostel is Second Home,” Straits Times, 24 January 1947, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

“Singapore’s Marine Hostel,” Straits Times, 10 April 1938, 32. (From NewspaperSG)

“Singapore Outing for Merchant Seamen,” Straits Times, 8 April 1941, 12. (From NewspaperSG)

“S’pore Zoo Starts from Scratch,” Straits Times, 20 October 1946, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

“The Men Who Helped to Build the New Supreme Court,” Straits Times, 6 August 1939, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

“The Seaman’s Friend Dies,” Straits Times, 20 January 1951, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

“The Sights – for Seamen,” Straits Times, 7 April 1949, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 25 November 1936, 13. (From NewspaperSG)

Wong Ah Yoke, “Satay Clubs in the Past,” Straits Times, 9 March 1997, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

NOTES

-

Also known as the “Singapore Guide for Merchant Seamen”. ↩

-

The book was published in June, July and September of 1934 ↩

-

“Notes of the Day – Willis’s Guide,” Straits Times, 17 January 1936, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A New Guide,” Straits Times, 30 May 1934, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

It was renamed The Mission to Seafarers in 2001. ↩

-

Mervyn E. Moore, Eighty Years: Caring for Seafarers: The Singapore Branch of The Mission to Seafarers (Singapore: Singapore Branch of The Mission to Seafarers, 2006), 2. (Call no. RSING 266.35957 MOO) ↩

-

Moore, Eighty Years, 3. ↩

-

“Missions to Seamen in Singapore,” Straits Times, 21 April 1936, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Helping Seamen in Singapore,” Straits Times, 11 May 1933, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore’s Marine Hostel,” Straits Times, 10 April 1938, 32. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Seamen’s Hostel is Second Home,” Straits Times, 24 January 1947, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Rev A. V. Wardle as cited in “Dangers Faced by Men of Merchant Navy,” Straits Times, 21 June 1941, 11 (From NewspaperSG); Also detailed in “Singapore’s Marine Hostel.” ↩

-

Clergyman’s Tribute to Singapore, Straits Budget, 8 February 1934, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dutch Sailors See Singapore,” Straits Times, 20 June 1940, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Naval Ratings on Trip to Johore,” Straits Times, 29 January 1940, 10; “The Seaman’s Friend Dies,” Straits Times, 20 January 1951, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“250 Sailors Go to Kota Tinggi,” Straits Times, 18 November 1936, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 25 November 1936, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Outing for Merchant Seamen,” Straits Times, 8 April 1941, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wong Ah Yoke, “Satay Clubs in the Past,” Straits Times, 9 March 1997, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Satay hawkers were featured on local picture postcards since the early 1900s. ↩

-

“Notes of the Day – The Ponggol Zoo,” Straits Times, 18 January 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Impressive New Building,” Straits Times, 5 September 1935, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Sights — for Seamen,” Straits Times, 7 April 1949, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩