The River of (Urban) Life in Singapore: The Street

Eugene Liow examines how population resettlement and the decentralising of retail activities in post-independent Singapore profoundly affected the vitality of certain streets, turning formerly lively streets into lifeless ones.

A city without street life is a city without urban vitality. As Jane Jacobs states in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1972), the life of the city is located in its streets. More than its functional capacity as a conduit for channelling people to different parts of a city, the street characterises it: “If a city’s streets look interesting, the city looks interesting; if they look dull, the city looks dull” (p. 107). It is through its streets that the city derives its personality, and it is on the streets that the social in the city is made visible. What makes the street a social fact is that “it has always included a set of assumptions about who would own and control it, who would live on it or use it, the purposes for which it was built, and the activities appropriated to it” (Gutman, 1978, p. 250). Indeed, the street is “the place where many of our conflicts or resolutions between public and private claims are accessed or actually played out” (Anderson, 1978, p. 1). It is also “a locus of social interaction and a linear passageway linking destinations” (Levitas, 1978, p. 228). As such, the street is a place where social encounters occur and a site through which the experience of everyday life in an urban environment are lived out.

Whether a location for watching street performances, meeting people, communicating with or just enjoying a sense of being with fellow human beings, the street is the predominant source of vitality of a city. It forms the space where people come together, participate in social exchange, are able to move about freely and enjoy the sociability that the street offers. It is the presence of people there at different times of the day that the street is filled with activity for as many hours in a day as possible. Such elements are what Jacobs refers to as urban vitality, and these constitute street life.

Yet, just as the life of a city is to be found in this feature of the urban landscape, the converse is also true. In Singapore, a number of once lively streets have over the years become “dead”, resulting in such spaces becoming dull, bland and generally lacking in the social. Such streets make the city just a little less interesting. This article examines how population resettlement and the decentralising of retailing activities in post-independent Singapore have profoundly affected the vitality of certain streets, turning formerly lively streets into lifeless ones.

The Singapore Street

The resettling of the population in the aftermath of independence from the British in August 1965, and the simultaneous decentralising of its retail activities (collectively regarded as the resettlement policy) were two crucial factors that profoundly affected the vitality of certain streets in Singapore.

In the period following independence, economic growth and combatting unemployment were two of many problems facing the government. Urban planning was one of the tools used to address them, and was regarded as a vital component to national development. It played a significant role in the eventual success of the export-oriented industrialisation strategy that the government undertook as a means to address economic growth and unemployment. At the same time, much of the population was by then already concentrated within a five-mile radius of the city centre, a vestige of British colonial policy in limiting the provision of sewage services and piped water to this part of the island. The availability of these public utilities made the city centre a popular place to live. However it also contributed to the problems of overcrowding, poor hygiene and the development of many squatter settlements which by the time of independence, was posing a serious health hazard.

It was also around this time that the ideology of pragmatism formed “the structuring centre of reasoning and rationalization of the policies by which Singapore has been governed since independence” (Chua, 1995, p. 48). This ideology extended to the realm of urban planning; the congested city centre was cleared, and along with it, all that was deemed unsightly, dirty and unhygienic. Singapore’s urban redevelopment came under the purview of two state agencies: the Urban Renewal Authority (URA)1 and the Housing and Development Board (HDB). Through them, anything that the government deemed as an obstacle to national development was obliterated, and the tone of “national survival” and economic development took precedence over other considerations. Many of the old buildings within the city centre were demolished and “sterilised” in order to make it cleaner and more orderly. The residents were also moved into low-cost public housing projects (“new towns”) built by the state under the banner of the HDB, freeing up space for more profitable commercial developments.

Once relocation to the fringes of the city centre just outside the five-mile radius began, the establishment of new towns like Toa Payoh and Queenstown gained prominence as “satellite towns” that became viable alternative commercial centres to the city. The resettlement policy led to the shifting of retail activities from traditional areas in the city centre. The net effect was that the crowds who once thronged Chinatown, Bugis Street and Kampong Glam dwindled. Historic city streets once filled with the flurry of everyday activities became gradually emptied of the hustle and bustle of street life, as the emphasis was on order, cleanliness and efficiency. They were relegated to purely functional conduits for the movement of people rather than as sites for social encounters. Inadvertently, the state had effected the emptying of the city, along with much of the cultural heritage and social activities that accompanied the groups that once occupied these spaces. Indeed, “by the ’90s the city centre had become an urban residential vacuum” (Siddique & Lim, 1999). We now turn to High Street and Chinatown as two examples that bear testament to the above.

High Street

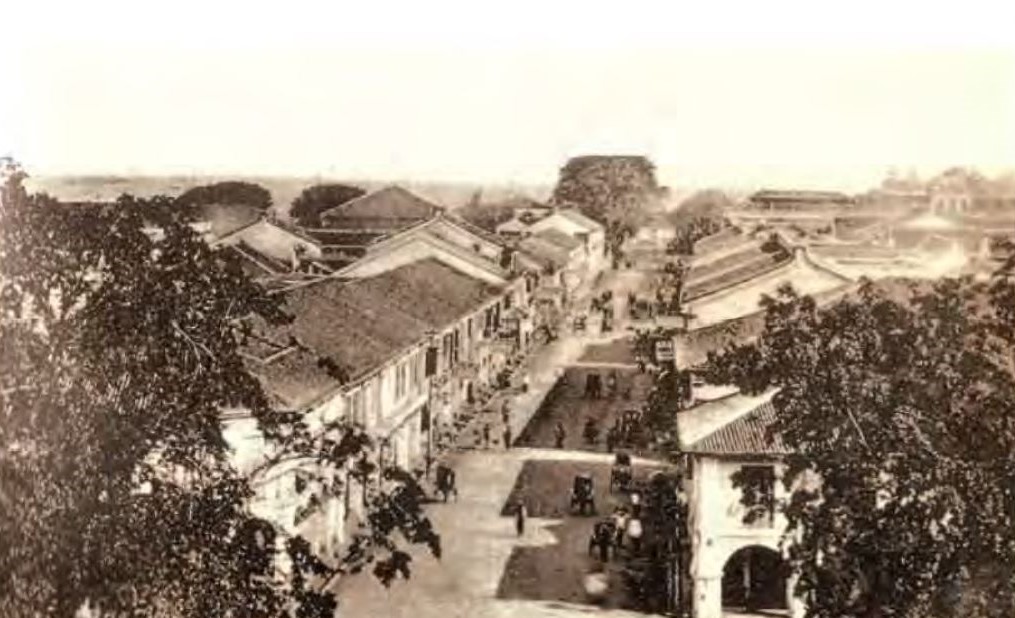

High Street was initially earmarked by the British to be the “Main Street of Singapore”. Located near the colonial administration centre, the British had grand plans for the street. While the motorcar had yet to be used on a large scale, High Street in 1870 was already built very wide. Judging by its width, it is possible to infer that the British had planned for that stretch to be bustling with activity. The street was also a fairly long one, stretching up to Fort Fullerton, near the mouth of the Singapore River.

High Street was one of the places where people went to obtain their daily necessities. There was a great deal of diversity in the goods and services that were sold – from silk, to studio photography services, to everyday necessities. Indeed, “the junction of [High Street and North Bridge Road] was an important and busy thoroughfare lined with glamorous shops and boutiques and serviced by trams” (Tyers, 1993, p. 43). However, after independence in 1965, the government began the resettlement policy that eventually led to people being relocated from the city centre to various new towns set up by the HDB. As the city centre was depopulated, the day-to-day goods formerly sold at High Street were gradually dispersed into the various HDB new town centres. These town centres became the places where residents could purchase daily necessities. As these goods that the residents bought were non-specialised, there was no compelling reason to travel to High Street to purchase them. This affected High Street’s businesses and left it particularly bereft of the large and dense population needed to sustain street vitality there.

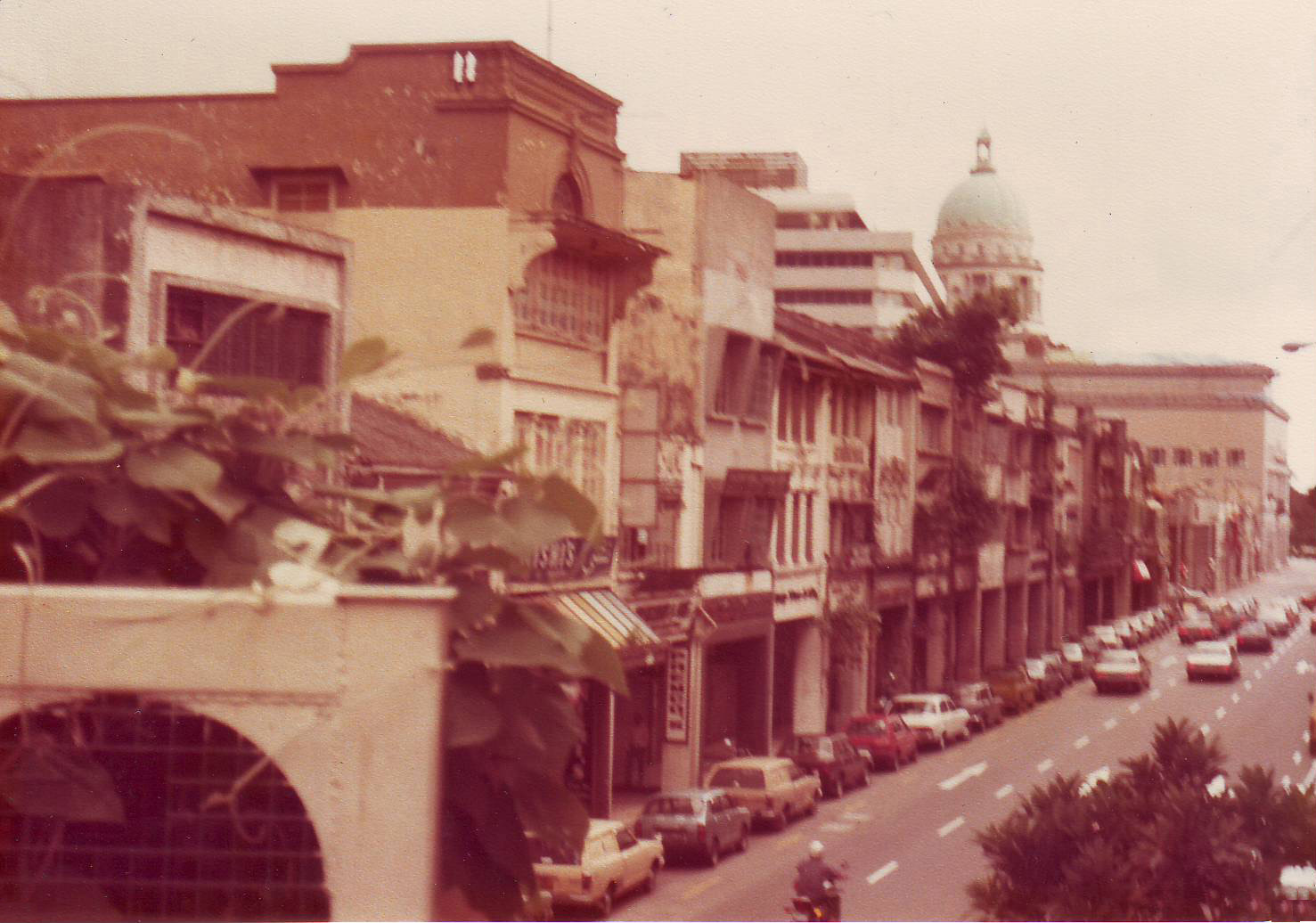

The status of High Street as the retail centre of goods and services was similarly challenged by the concomitant development of Orchard Road as a major shopping area. With the state’s efforts to relocate high-end retailing to Orchard Road in 1976, High Street lost many of its specialised shops. Popular departmental stores that were located near High Street such as Robinson’s, John Little and Metro were gradually relocated to Orchard Road, culminating in its eventual demise as a social marketplace.

Today, High Street is a 100-metre-long road that is relatively quiet, an empty stretch of concrete and mortar devoid of the street life that the British had envisioned. There is little activity on the street, a stark contrast to its heyday in the early and mid-1900s. Ultimately, the vitality of High Street as a shopping destination diminished as a result of the decision to depopulate the city centre into new towns, and the demarcation of Orchard Road as the high-end shopping district.

Chinatown

“Chinatown” is a collective term used to describe an area located in the southern part of Singapore. This area is bounded north of Cecil Street, west of Pickering Road and Church Street, east of Maxwell Road and Kreta Ayer Road, and south of New Bridge Road. Stamford Raffles had planned for the Chinese communities to congregate in this enclave, and it constituted one of the many planned sites in his town plan. Within this area lie several streets that once housed much of the Chinese population in Singapore.

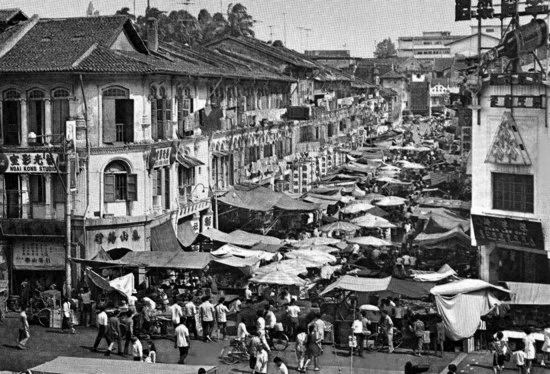

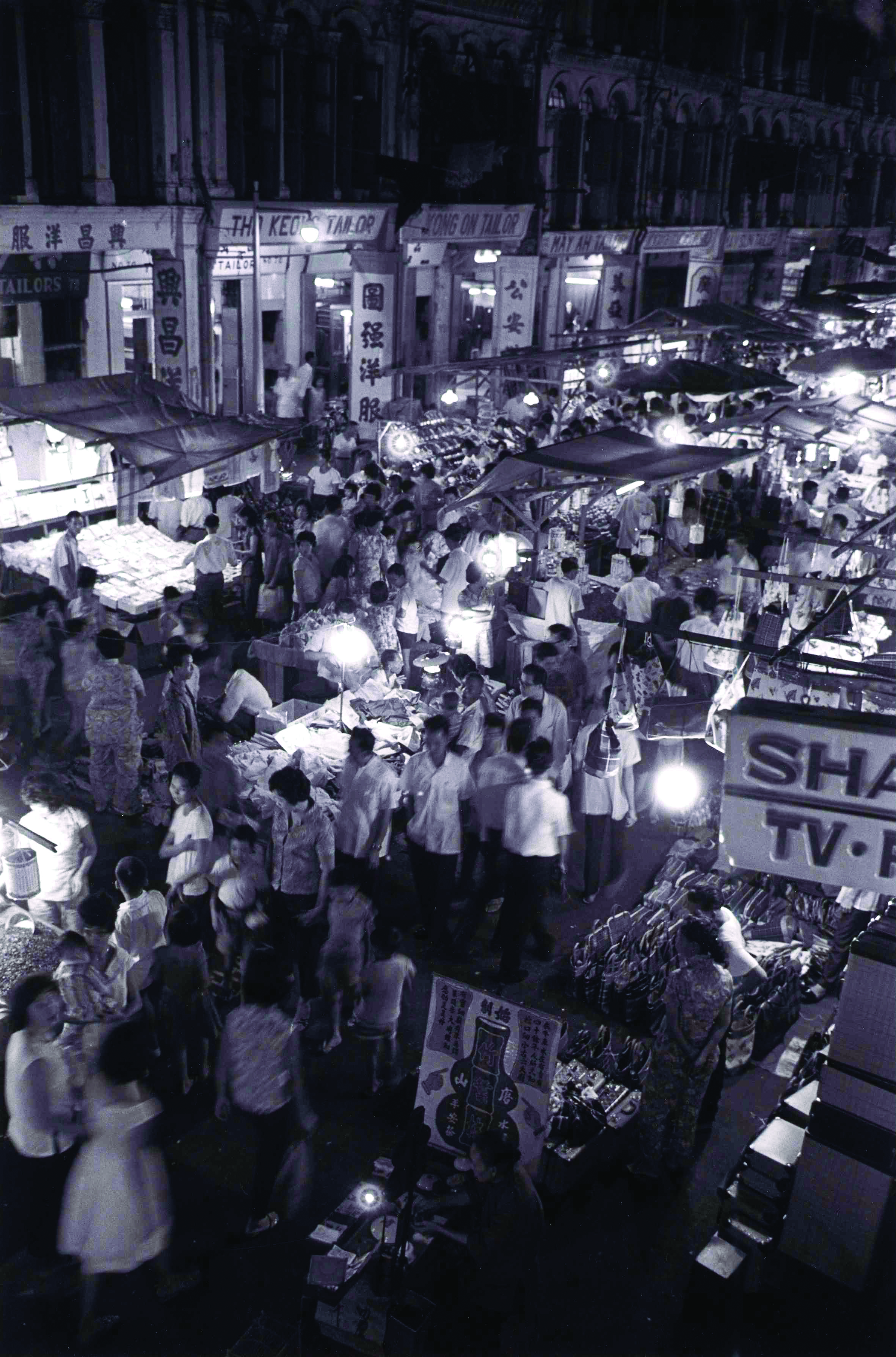

While each street has its own unique character, what binds them together is the fact that these streets once collectively possessed an active and vibrant street life. There was a large density of people living and working within this area; as Kaye indicated, “the average population density [of Chinatown] in 1947 was 230,000, or over a quarter of a million persons, per square mile”. He observed that a street has “a considerable amount of social intercourse on the road and pavements of the streets themselves, such as marketing, gossiping, children playing, etc” (Kaye, 1953, pp. 6–7), and the streets of Chinatown, particularly Upper Nanking Street (his object of study) was no exception. Like High Street, the decline in the vitality of street life in Chinatown was a consequence of the resettlement policy, which effectively shifted out the bulk of the residents necessary for sustaining that level of street vitality.

This lack of permanent dwellers is the primary factor for the loss of street life in Chinatown. The inhabitants of Chinatown used to live in two- and three-storey houses, and such structures make up the bulk of buildings in the area.2 These old shophouses were where the inhabitants lived, worked and played. These three elements were interlinked and interdependent. Depopulation effectively removed the “live” element, which is the most important as it is from this that the other two are derived, and on which they are dependent. The removal of the “live” factor impacted this delicate “ecological” system. The so-called suburbanisation of the populace meant the lack of a critical mass required for the existence of street life in Chinatown.

The resettling of street hawkers had a similar impact. As Chua states, “[c]anopied hawkers effectively pedestrianised Chinatown’s streets until 1983 when the hawkers were resettled by the Ministry of the Environment” (1989, p. 19). Citing issues of orderliness and hygiene, the resettlement of the hawkers to “hawker centres” essentially removed the final traces of street life remaining in Chinatown. People had one less reason to go there; those who had done so for the food no longer came, further reducing the population density of the place, which in turn impacted street vitality. With the removal of the “live” element represented by its residents, street life in Chinatown was effectively decimated, reduced to a shadow of its former self.

Reviving Chinatown

This lack of vibrant street life persisted even when efforts were made by the government to revive this part of the city. In the 1980s, the government began a conservation movement in response to the demand of tourists searching for but failing to find an “exotic” East in Singapore. Chinatown was designated as one of many areas earmarked for conservation. The results are visually striking: brightly coloured rows of restored shophouses now line its streets. Improvement and restoration works were conducted on the “traditional Chinese Baroque-style buildings” (Li, 1998). Yet such efforts were criticised by citizens for the transformation of Chinatown into merely “another promotional effort for the tourists, far removed from the practicalities of [the locals] daily lives” (Kong, 2003, p. 361). Some viewed the present Chinatown “as ‘a kitsch representation of mainland Chinese icons’, and […] a product that was merely artistic but lacked the soul of Chinatown past” (The Straits Times, 1999).

Singaporeans were dismissive of Chinatown as they “are not convinced that conservation is for locals” (Kong, 2003, p. 361). They regarded the conservation process as an exercise designed to appeal to the tourist trade, as opposed to something meaningful for them. Ironically, the tourists themselves regarded the “new” Chinatown as somewhat artificial, mentioning that “the restored shop houses are nice, but the place still lacks something” (Tan, 1996). In contrast to its earlier, more bustling days, when Chinatown was once “said to be a place with no night” (Kong, 2003, p. 361),3 the overt focus on the presentation of Chinatown as a tourist attraction has resulted in it becoming “a ghost town after 6 pm” (Ibid.) when the tourists leave. Such a situation continues to persist even until today.

Efforts to recreate a bustling Chinatown were regarded by some as contrived and insipid because the “live” element previously contributing to the generation of street life was not, or perhaps could not be taken into consideration.4 The STB and the URA’s attempts to recreate the past vitality of Chinatown with an overt focus on the physical landscape reveal little consideration for social elements like “the genuine longstanding trades and small businesses, and the concomitant familiar retailer-client relationships” (Ibid.). These represented the “soul” of Chinatown – the everyday lived experiences of the residents that can neither be generated nor reconstructed at will by top-down policies. Consequently, the resettlement policy initiated in the name of urban redevelopment led to the removal of the social fabric needed to create and sustain street life. Coupled with the lack of participation in these places by the local population, these factors will continue to limit the level of activity in the streets of Chinatown.

The Case for the Vibrant Singapore Street

Despite the resettlement policy, Singapore is not entirely without vibrant streets. Examples include Little India and Waterloo Street, which remain vibrant because the former has a large and stable population in the form of foreign workers from South Asia providing the necessary density needed, while the presence of an important Chinese temple in the latter helps draw Singaporeans from all over the island. In both places. the URA assisted in improving the conditions for street life to flourish through promoting Little India as a tourist destination and pedestrianising Waterloo Street. However, these vibrant streets are few and far between in Singapore. Despite efforts by the URA and the STB, streets like High Street and Chinatown have yet to recover from that blow, and are unlikely to do so. We can juxtapose the two with Orchard Road, which is officially designated as the place to site hotels and shopping centres in an attempt to capture the tourist dollar. Here, vibrancy takes on a different connotation, one of mass consumption and popular culture, and this has further heightened the level of activity along this stretch of road. While the last five years have seen even more shopping malls and tourist projects being built (such as the casinos at Resorts World Sentosa and Marina Bay Sands) in the supposed effort to enliven Singapore, one must not forget the importance of street life as part of the vitality of the city and a constituent of national identity.

Gans (1991, p. 41) criticises contemporary city planning “for giving higher priority to buildings, plans and design concepts than to the needs of people, and for trying to transform ways of living before examining how people live or want to live”. On this note, the state (being a decisive factor in influencing street vitality particularly in Singapore) might figure into urban planning greater space allotments to citizen-initiated activities that can contribute to bringing back a kind of natural vitality to once-lively streets. This will also entail a shift from the pragmatic emphasis on economic development, detaching urban renewal projects from tourism goals, to one focused instead on the rekindling of the social in Singapore’s historic, albeit forgotten, streets. As William Whyte states, “[t]he street is the river of life of the city, the place where we come together, the pathway to the centre”. Without street life, monuments and numerous malls will stand in a potentially lifeless landscape.

The author would like to acknowledge Associate Professor Ho Kong Chong of the Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore for reviewing this article.

Research Assistant

Department of Sociology

National University of Singapore

REFERENCES

Anderson, S. (1978). People in the urban environment: The ecology of streets (pp. 1–11). In On streets. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Call no.: RART q711.73 ONS)

Chua, B.H. (1995). Communitarian ideology and democracy in Singapore. London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705 CHU)

Chua, B.H. (1989). The Golden Shoe: Building Singapore’s financial district. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 711.5522095957 CHU)

Gans, Herbert J. (1991). People, plans, and other policies: Essays on poverty, racism, and other national urban problems. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gutman, R. (1978). “The Street Generation”. In S. Anderson (ed.), On streets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 249–264. (Call no.: RART q711.73 ONS)

Jacobs, J. (1972). The death and life of great American cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

NOTES

-

The URA came into being on 1 April 1974. It is the state agency through which urban planning, development and renewal are carried out. Its earlier approaches to the preservation of streets and street life were “one-size-fits-all” and detrimental to the preservation of street life. At present, they seem to have changed their approach and are individualising it to the areas slated for current preservation, rather than applying a single overall solution. ↩

-

It is important to also consider the realities of the residents living there then. Many parts of Chinatown were overly congested and unsanitary, where diseases and fire alike could easily be spread. Much of it was thus in dire need of refurbishment, renovation and decongestion in order to make them less of a health and fire hazard. ↩

-

An exception will be the few weeks leading up to Chinese New Year. Ethnic Chinese from all over Singapore would head to Chinatown to purchase festive foods, decorative items and/or just to soak up the festive atmosphere. Once that is over, however, Chinatown reverts to its regular state of being relatively quiet and devoid of street life. ↩

-

For instance, the reason for the large numbers of street hawkers and traders in the streets of Chinatown was due to the “high employment and underemployment”. (Chua, 1989, p. 12) at that point in time. The process of industrialisation is as much responsible as the resettlement policy contributing to this group of people eventually disappearing from the streets of Chinatown, and with them, the level of street vitality that they helped to generate. ↩