A Founder's Literary Legacy: The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S Rajaratnam

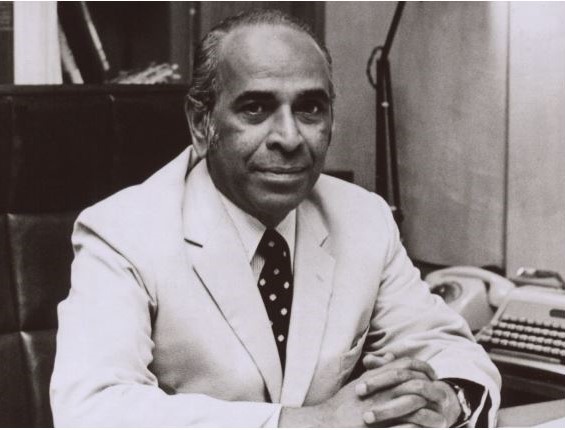

One of Singapore’s founding leaders, S. Rajaratnam is today best known for drafting the Singapore Pledge and for being the country’s first Foreign Minister. His biographer Irene Ng, who recently edited the anthology, The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam, reveals his little-recognised literary side and discusses its importance to Singapore.

S. Rajaratnam is perhaps best remembered for his visionary role in shaping the national ideology and framing the foreign policy of Singapore as one of its founding leaders charting a yet-unknown future. What is less recognised is the rich literary legacy he left behind. Its creation predates the independence of Singapore in 1965, and even its self-governing status in 1959.

Before there was the politician and ideologue, there was the storyteller and the writer. Indeed, the conception and development of Singapore’s national ideology and foreign policy arguably owes much to the imaginative writer and creative thinker in him.

I would like to divide this essay into three parts. First, a brief introduction to his stories and radio plays. Second, the context in which he wrote the stories and plays. Third, an examination of the importance of his literary legacy.

Introduction

It is important to recognise that Rajaratnam was not just any writer, but a great one, once acclaimed in London – the centre of the English literary scene – where he lived for 12 years from 1935 to 1947. During the bleak years of World War II, when he turned to writing to eke a living, he proved himself to be a writer of uncommon imagination and talent.

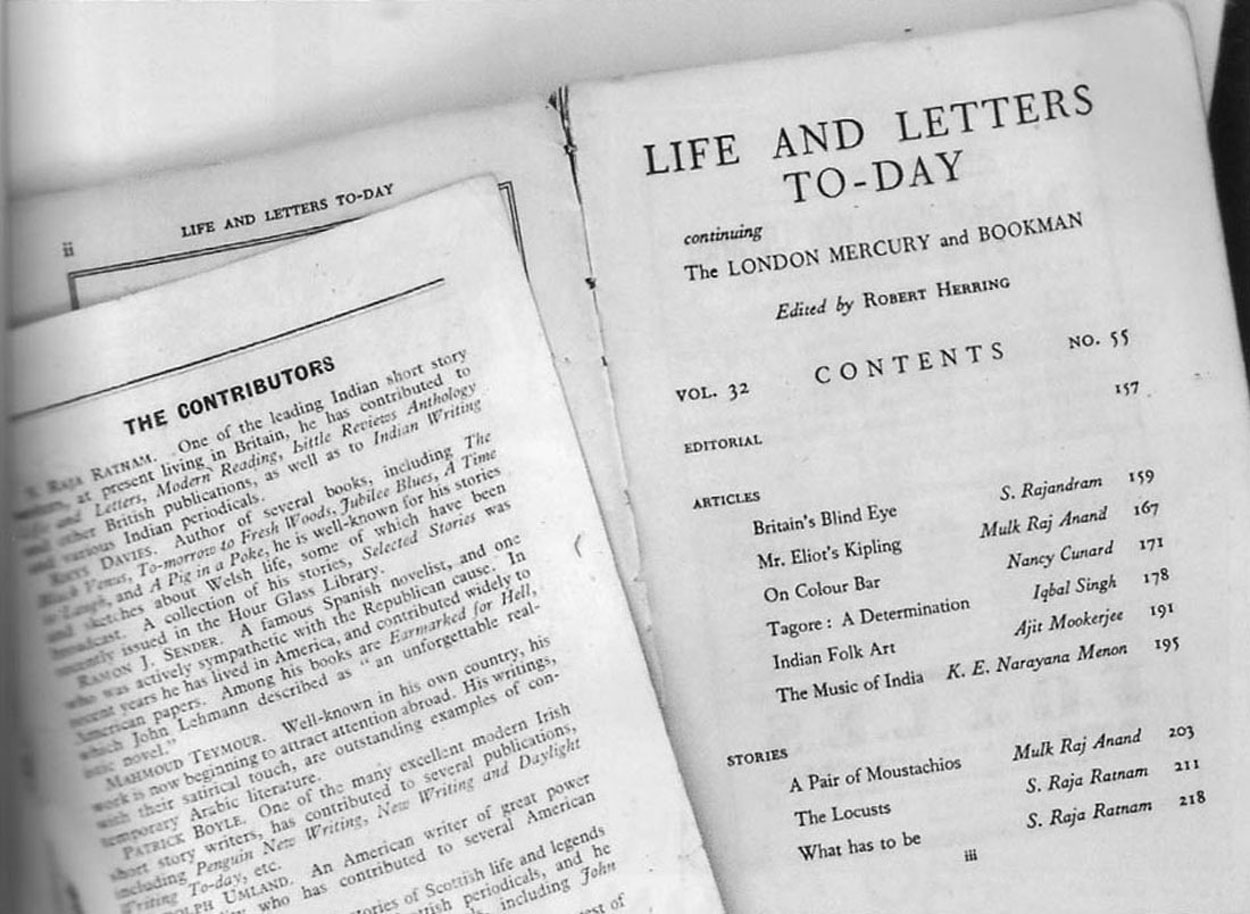

His short stories were published in several journals and anthologies in the 1940s, and caught the attention of literary greats E.M. Forster and George Orwell. Forster described Rajaratnam’s debut “Famine”, published in 1941, as “touching and well-constructed” in one of his radio talks for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Orwell, who would later achieve fame for the political novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, was working at the BBC in the early 1940s and invited Rajaratnam to write radio scripts.

By the mid-1940s, Rajaratnam was billed as “one of the leading Indian short story writers” in some anthologies. His reputation among the literary cognoscenti was sealed when his work appeared alongside those of literary greats in an international anthology published in 1947. The volume was titled A World of Great Stories: 115 Stories, The Best of Modern Literature. The anthology also featured works by Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, John Steinbeck and James Joyce, to name a few.

Rajaratnam’s stories addressed themes of disaster and death, oppression and injustice, and the fears and follies of man, but also coursing through them is the transformative power of the human spirit and of reason. Although most of his stories are set against South Asian and Malayan backdrops, they are not simply stories of a time or place, but a sophisticated reframing of the forces and ideas that shaped the world in which we live. In his stories, we follow the fortunes of characters as they define themselves or are defined by various combinations of their past, the choices they make, and the forces that act upon them. Do characters make their fate or suffer it?

His stories are powerful in their imagination and notable for their literary quality. Some of them, given their universal themes, have travelled beyond the English-speaking world and have been translated into French and German.

But it is at home – Malaya, which at that time included Singapore – that his passion really lay. As one of Singapore’s founding leaders in 1965, he drew from his belief in the transformative power of the mind and his past literary experience to imagine a Singaporean Singapore at a time when racial and religious divisions were omnipresent. Defying the evidence before his eyes, he envisioned a nation pulsating as one people. He clothed his vision in prose and gave it shape and shine as the unifying national creed.

One can find its ideological basis in the radio plays that he wrote for broadcast over Radio Malaya in 1957, two years before the People’s Action Party came into power in 1959. Then a newspaper journalist and a freelance radio scriptwriter, he animated his ideas through a picaresque group of characters for a six-part drama series, A Nation in the Making.

They were broadcast over Radio Malaya at a time of political upheaval, when Singapore and the peninsula were grappling with colonialism and agitating for freedom.

They aimed to shape public opinion on urgent issues of the day – in particular, the making of a nation. Prior to the advent of television in Singapore in 1963, radio drama was a popular form of entertainment and education.

He used witty dialogue to engage the listener. But there were life-and-death issues at stake, and a serious decision the people needed to make, at a time of intense political ferment and uncertainty: Should Malaya go the way of racial politics and incompetent populist leadership?

In his radio plays, there is a recurring message: “we can create the sort of nation that we want”. This is a discourse of reason, of civil argument and debate, one based on a relationship of trust and faith.

As one of his characters in the radio scripts says: “We must make an act of faith that people can be made to think, that you can appeal to their reason, and that you can bring out the decent and human qualities in them. We must believe in this or perish. If we believe that our people are essentially reasonable and decent, then we can believe that they will understand us when we say that, unless we become a nation, we will destroy ourselves.”

He was fearless in attacking the problems of the day, and used radio dramas as sources of ethical instruction and political education. Reading them today, his words still seem immediate, powerful and courageous.

Reading the scripts, one is struck by the clarity and conviction with which Rajaratnam laid out the arguments against racial politics and the idea that a nation should be built on a common race, religion or language. He deployed quotes from leading thinkers, such as Ernest Renan and John Stuart Mill, to contend that the vital element that brings a nation to life is a people united by a sense of common history and common destiny – or as he quoted H.A.L. Fisher, “common sufferings, common triumphs, common achievements, common memories and common aspirations”.

In reading his plays, what comes across with unmistakable clarity is his prodigiously imaginative flair. Their recordings, however, have disappeared into thin air. I found their scripts among Rajaratnam’s private papers in the course of my research for his biography. Titled The Singapore Lion: A Biography of S. Rajaratnam, the biography was published in early 2010. The radio scripts are now preserved in the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Library, which houses the S. Rajaratnam Private Archives Collection.

Context

The seven short stories, which I collected in the book The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam, were written during his transformative years in London.

When Rajaratnam arrived in London to study for his law degree at King’s College in 1935, he was aged 20. He came from a sheltered background, raised in the rubber plantations of Seremban by his caste-conscious Jaffna Tamil family who were devout Hindus. He was not interested in politics and had little direction in life.

By the time he left London 12 years later in 1947, he was a changed man – a man with a political vision with strong convictions in justice and equality. He had also found his calling – to be a writer and journalist – and had achieved a measure of literary acclaim.

London was the capital of the English literary and intellectual scene. He was swept up by the moral and political ferment of the times. As the drama of nationalism and the danger of fascism became obvious and urgent to him, he sought out answers. He found himself gravitating towards Marxist and Fabian circles. A budding bibliophile, he listened to people talk about books at book launches.

He was close to the radical Indian writers and nationalists in London and had connections with left-wing editors and politicians from various countries.

Then came the war in 1939. And the terror. The anxious war years in London were a major turning point for him. The unfolding horrors of Nazism, the dehumanising madness of war and the senseless persecutions had shown the overwhelming power of the irrational.

He was assailed with a deep sense of doubt about how to make life count – indeed, how to live – in this time of crisis. During this dark and intense period, as he re-examined his assumptions of life, his roots and identity, he devoted himself to the discipline of deep reflection and to the exercise of the moral imagination.

This imagination is reflected in his short stories. He wrote them in the midst of the Blitz, when bombs rained down almost every night on the capital.

Amidst the rubble and the terror, he wrote to get hold of some kind of truth, to get to grips with the realities of life, to make sense of society and the individuals in it, to discover a vision of society that is worth living and fighting for.

He used metaphor, humour and irony in his writings to provoke people to think, to find their own answers. He wrote to get across some ideas, to expose falsehoods, to make people re-examine their deeply held beliefs and assumptions.

During that uncertain period in London, he was already worrying about the politics back home in Malaya. In the mid-1940s, before returning to Malaya, he was already writing about this in commentaries, analysing the problems facing Malaya, particularly the vexing question of how to integrate the different races into one political community. These worries received full attention in his radio scripts for Radio Malaya 10 years later, in 1957.

In his radio plays titled A Nation in the Making, he provoked his listeners to think about what ultimately binds a nation together, opened up the explosive issues of race and religion, and appealed to their reason to find answers.

His radio plays deserve greater study for their contribution to the idea of a Malayan nation – which Singapore was part of at the time – and the contested notions of the beginning of Malayan history. They stand out for their deep insights that pass the test of time.

Through his writings at this seminal stage, one can trace the formation of Rajaratnam’s views on fundamental questions at a time of great moral and political confusion. They offer sharp insights into his values and ideals. The foundation of Singapore is built upon the rock-solid convictions of exceptional men like him.

One of his most important ideas was on Singapore’s national identity. He was keen to ensure that the younger generation shared his unhyphenated vision of a Singaporean Singapore, as opposed to a Singapore that is based on separate communal identities. He believed in the ability of Singaporeans to transcend their racial, cultural and religious classifications to create a shared national identity to which they give their primary loyalty. For him, this was an act of will and faith.

Importance

The themes in his early writings are still relevant today, if not even more relevant. The transformation of a people from different races and religions, and from different lands, into a united nation is not an easy process. It needs the kind of momentum that comes with moral outrage, conviction and fear, but it also takes someone to do the hard grind, to focus on the analysis and provide the factual and ideological ammunition.

Rajaratnam’s writings, be they fiction or journalism, make people think. But they would not get things done; they would not solve problems. At the time when Singapore faced a crisis of political leadership, Rajaratnam, Lee Kuan Yew and others with similar convictions stepped forward. They entered politics to build the kind of society they envisioned, and pursued that great aim with a high heart.

I believe that the plays are especially important, as they hold the ideals that underlie what was to be his life-long quest for a Singaporean Singapore, a fair and just society rid of irrational prejudices and intolerance. They hold questions that reverberate through time and that demand an answer: How realistic is this dream of a Singaporean Singapore? How far have we come in realising it?

In Singapore, our brand of multiculturalism is an ongoing experiment. The Singaporean Singapore that founding leaders such as Rajaratnam envisaged for this land of immigrants is one that embraces immigrants and transforms them into Singaporeans who stand united as one people.

“We the people of Singapore, pledge ourselves as one united people, regardless of race, language or religion” – this line from the Singapore Pledge is a central vision of Rajaratnam’s.

In one of his radio plays are less familiar words by him, but which still give us pause today. A character in his radio script muses on building a nation based on nationalistic sentiments: “There are good sentiments and bad sentiments. There are emotions like love, compassion, brotherliness which have made men better men and nations better nations. There’s the patriotism which can better be described as love of country. There is jingoism and phoney patriotism which is arrogant and full of hatred. But a good nationalist wants his country to be admired by other countries.”

Rajaratnam was a good nationalist. In spite of the many disappointments and the torrent of abuse that came his way, he was also an optimist. He believed in a Singaporean Singapore and was unflinching in reminding us that we should be doing better when we failed to live up to the ideals in the National Pledge.

It is to be Singapore’s lasting fortune that Rajaratnam chose to use his imaginative talent and creative skills to build up the nation, laying the foundation for the ideals that will always be crucial to our quest for a Singaporean Singapore.

Singapore was also fortunate that Rajaratnam, who was born in Ceylon, raised in Seremban and spent 12 years in London, chose to make Singapore his home and to devote the rest of his life to its service.

An appraisal of his early writings puts in perspective his original contribution to the genre as a pioneer in Malayan writing in English. Robert Yeo, in the introduction to his selection of Singapore Short Stories Vol. II, credits Rajaratnam for being the earliest fiction writer in English. Ban Kah Choon acknowledges that “the first stories written by S. Rajaratnam in the early 1940s are clearly important, laying, as it were, the desire to narrativise local events and to think imaginatively with a local voice”.

Indeed, Rajaratnam’s early writings add depth and distinction to our literary legacy and deserve to be read, celebrated, interpreted and reinterpreted. Yet, so few Singaporeans have read them. It seems not a little ironic that our students read works by Western authors with hardly any link to our social and cultural contexts, but not those of the country’s own founding leader, once recognised by the Western literary circles for producing among the greatest short stories in the world. One hopes this will soon change.

Irene Ng is a writer-in-residence at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies and has been a Member of Parliament since 2001. She compiled and edited The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam (2011). She also wrote The Singapore Lion: A Biography of S. Rajaratnam (2010) and is currently writing the second volume of his biography.

Irene Ng is a writer-in-residence at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies and has been a Member of Parliament since 2001. She compiled and edited The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam (2011). She also wrote The Singapore Lion: A Biography of S. Rajaratnam (2010) and is currently writing the second volume of his biography.