Sago Lane: “Street of the Dead”

The older generation of Singaporeans who lived, grew up or worked in Chinatown during the 1930s to 1960s would remember the “death houses” of Sago Lane, scattered intermittently among residential dwellings.

In the modern hospices of today, qualified healthcare professionals, together with a pool of volunteers, provide palliative care and succour to the terminally ill to ease their suffering as they make the most of their last days on earth. These hospices also offer programmes that cater to the medical, psychological, social and even spiritual needs of their patients and bereaved family members.

In stark contrast, the death houses or “Sick Receiving Houses” on Sago Lane were the abodes of last resort for the terminally ill, aged and infirm early immigrants to spend their final days in solitude, misery and, for some, in excruciating pain. “Death Houses did not assume the responsibility for the well-being of a person. They merely functioned as bed spaces for people to die.”1

Origins of Sago Lane

Sago Lane has several colloquial variations in its name: it was known as ho ba ni au koi (Hokkien for “the street behind Ho Man Nin”). Ho Man Nin was the name of a well-known Chinese singing hall on Sago Street.2 In Cantonese, Sago Lane was also known as Sei Yan Kai (Street of the Dead), referring to the death houses that were once located along this street,3 and as Mun Chai Kai, named after an undertaker, Kwok Mun, who established the first death house there.4

In the mid-19th century, sago was a major export of Singapore. Raw sago that was imported from Sumatra and Borneo were processed in sago factories here and then exported to Europe and India. In 1849, there were 17 (15 Chinese and two European) sago factories operating in Singapore,5 increasing to 30 in total by 1850. Many of these factories were located at Sago Street and Sago Lane.6 When jinrickshas were introduced to Singapore in 1880, a jinricksha station was set up on Sago Lane.7

Chinatown then was divided informally into distinct dialect enclaves, with the Cantonese residing in and around areas such as Smith Street, Sago Lane, Sago Street, Pagoda Lane, Trengganu Street, Temple Street, Club Street, Ann Siang Hill, Keong Saik Street and up to South Bridge Road and New Bridge Road.8

Sago Lane gained its unsavoury reputation when death houses began operating in the area in the mid-19th century. Death houses were also established along Spring Street, opposite the Metropole Theatre.

Death Houses

Prior to World War II, residents in Chinatown lived in very crowded, squalid and unsanitary conditions.

Many of the poor and lower-income people resided as a family unit in monthly rented cubicles, with six to seven cubicles (averaging 2 metres by 3 metres) being partitioned and subdivided on a single storey level (24 to 30 metres in length) of a two- to four-storey shophouse.

The small, dingy, airless and horribly cramped quarters provided poor living conditions particularly for the elderly who had contracted terminal diseases, were bedridden and nearing death. As the able-bodied adults had to work long hours, thus leaving no one to care for the infirmed elderly, many on the brink of death were sent to the “Sick Receiving Houses” by their families. This was also motivated in part by a commonly held Chinese superstition that evil spirits would haunt the house where a person had died, and it was very costly to conduct an exorcism to make the house habitable again for the living.9

A few of the critically ill who were without relatives and had a bit of money to spare also voluntarily chose to live out their last days at the death houses instead of the clean and sanitised environs of a modern hospital, having resigned themselves to their fook sau (lacking long life) fate. Some were also terminally ill patients who had been discharged from the hospital and left there to pass on.

The proprietors of these death houses charged different lodging rates depending on the health of their occupants, with those who were nearing imminent death paying less. A hundred and fifty dollars was the standard charge, including a $10 admission fee and $1 a day for the night and day attendants, including “the fee for laying the dead out in the funeral silken robes that every Chinese, no matter how poor, hopes to be buried in”.10

In a death house, when a resident had ceased breathing, a doctor would be called in to certify the death. The corpses of those who had just passed on would have their faces covered in red or yellow paper11 and their bodies would be draped in straw mats before being placed in coffins, which were then sealed up and placed on the ground floor to lie in state while awaiting burial. As embalming was not a common practice then, the corpses would start to rot, giving off a stench after a day or two, particularly if there were three to four coffins placed together at a time.12

The ground floor also accommodated the critically ill and poverty-stricken residents, while those who could afford to pay more stayed on the second and third storeys. Many residents were emaciated, with some suffering vocally in pain, while others slept quietly, but all were waiting for their time to die.13

In an oral history interview from the National Archives, Dr Lo Hong Ling, who was a medical doctor practising at Smith Street during the 1960s, described many instances of how people who were on their death beds would start to see and hear strange things when they closed their eyes at night, such as the clanking of chains and the sensation of being dragged away by people wearing the faces of bulls and cows.14

At Kwok Mun, one of the oldest licensed death house establishments, wooden bunks arranged dormitory-style were provided for the residents with separate male and female wards on the upper floors. “Kwok Mun occupied two shophouses standing side by side at Sago Lane. The ground floor of one shophouse serve[d] as the admission room. The other was the mortuary.”15

In other smaller and less well-furnished unlicensed death houses, there was no segregation of the sexes; men and women alike slept on thin straw mats, old blankets donated by well-wishers or thin mattresses provided by their relatives. These would be discarded upon the deaths of their users. Residents who could afford to pay more were given better quarters, such as a corner for more privacy.16

The caretaker of the death house provided minimal care for the residents. Meals were provided for the residents by their own relatives, who delivered them in tiffin carriers. Poorer residents had their meals served on banana or yam leaves or even wrapped in newspaper.17

Most residents would live for only a few days or up to a week after moving into the death house, although a few lingered on for one to two months before succumbing to their illnesses. A miraculous few even survived, recovered and eventually returned home.18

Relatives and friends would wait in the death house and gather near the dying person, leaving for home only on short breaks for a bath and change of clothes. They would also “entertain their friends and relatives with beer, brandy, mineral water and Chinese tit-bits”.19 Friends and relatives keeping vigil into the night would also play mahjong and card games.20

Wealthier families held dinner feasts outside the death house as a pre-departure memorial for the dying relative. Families would borrow money at up to 20 percent interest rates, incurring debts to fund such death watches.21

The landlord, caretaker, workers and cleaners of the death house also lived on the premises, in quarters behind the ground floor. Death houses were open 24 hours a day with staff working day and night shifts.22

In 1948, there were seven death houses in Singapore, two of which were licensed by the municipal health authorities as “Sick Receiving Houses” while the rest were unlicensed.23 Two well-known licensed Sick Receiving Houses on Sago Lane were Fook Sau and Kwok Mun.24

Death houses served a practical and essential service in the densely populated and built environs of Chinatown by providing temporary housing facilities for the terminally ill on a multi-use property where funeral ceremonies could be performed and as a funeral parlour where wakes could be held.25

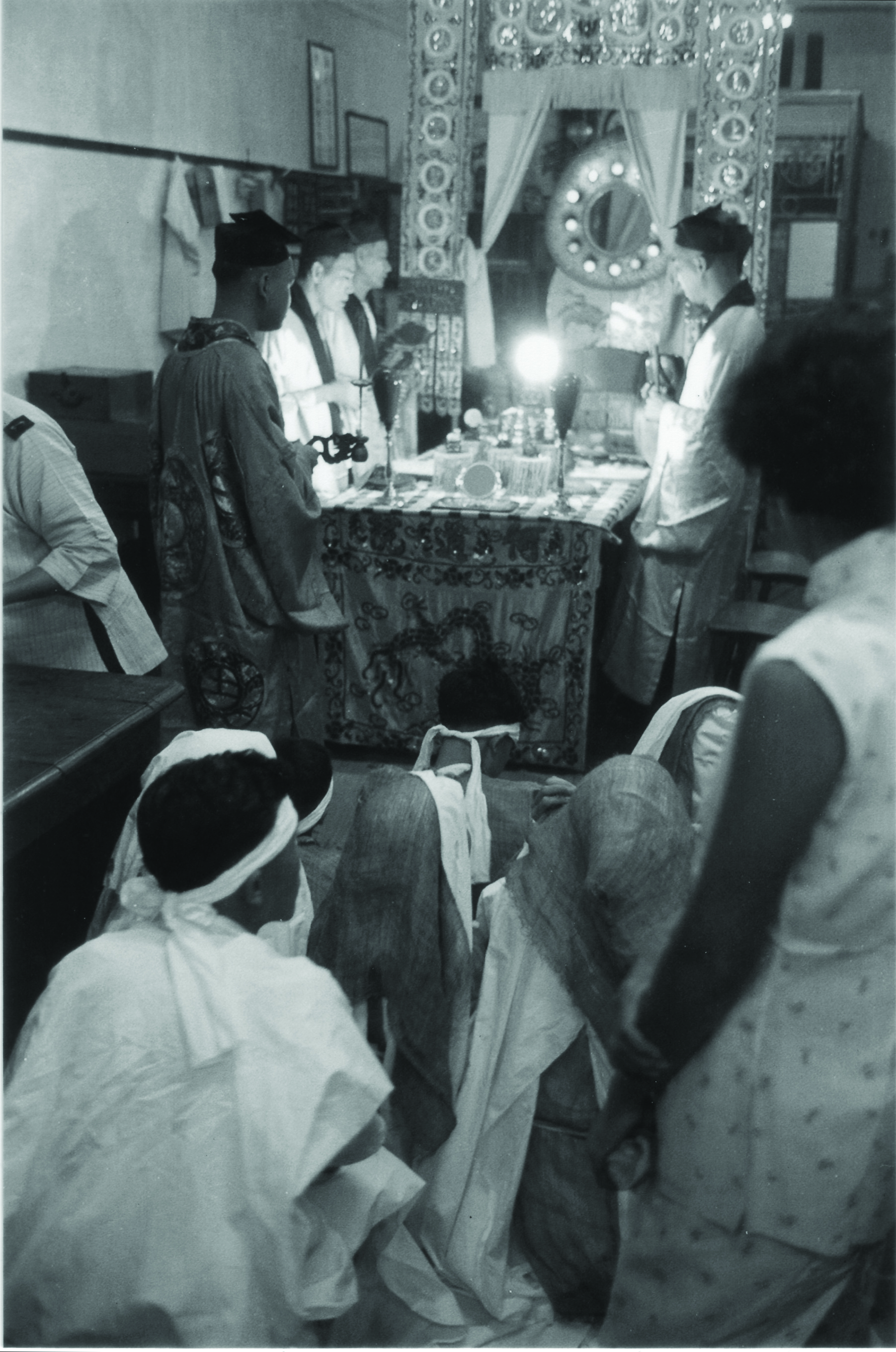

Funeral Rites

Simple funeral rites were performed on the ground floor, restricted to a specific area, near the front entrance. With six deaths occurring every day on average in the late 1940s,26 it was not uncommon for funeral ceremonies to be held for two to three corpses simultaneously, with different priests engaged by the different families. The ceremonies were also performed along the main road or outside death houses if there was insufficient space indoors.

The scale of the funeral ceremonies depended on the financial circumstances of the family. For simple ceremonies, relatives would say prayers, squat outside the death houses and burn joss paper in wash basins.

At around 11am daily, cacophonous music from percussion bands and wind instruments could be heard from Sago Lane, serenading the dead as they embarked on their final journey. At night, the street became an even busier hive of activity with long-drawn chanting from priests, accompanied by the steady beating of drums and gongs, the resounding clash of cymbals and the mourning cries of the bereaved. Visiting mourners and wreaths contributed to the crush of human traffic.27 As the frangipani blossom was commonly used in wreaths, the heavy scent of the flower frequently permeated the entire street.28

Due to the strong clan spirit among the Chinese community, when poor immigrants were unable to afford funeral expenses, clan associations and temples would rally together and contribute the pek kim (Hokkien for “white silver”) to defray funeral costs.29 Coffin shop owners would also charge nominal prices for coffins that well-wishers would purchase for the impoverished. Death houses would also sometimes waive the coffin and burial costs for the poor. Helping the poor was believed to be a praiseworthy act, and manifold blessings would be bestowed on the giver in return.30

The coffins used for the poor were basic makeshift constructions: four planks of cheap wood nailed together, just big enough to hold the corpse. “The cost of a cheap coffin, transport to the cemetery and other incidentals started at $120 and went up to $1,500 for the rich.”31 The rich were able to afford bigger coffins and complement it with a lavish display of “cooked food, cracker firing and scattering of paper money”.32

Burial was the norm among the Chinese and the burial ground of choice among the Cantonese during the 1950s to 1970s was at Kampong San Teng (where the Bishan housing estate is currently located).33

It was – and still is – a Chinese custom to hold a wake lasting a duration of an odd number of days, such as three, five or seven days, partly out of superstition and also to allow time for far-flung relatives to come and pay their respects. The Chinese believed that holding a wake for an even number of days was unlucky, as it would cause the same event – death – to occur again.34 Prolonging the duration of the wake and hence incurring a heftier bill was also seen as an indication of one’s social status.35 Caretakers at the death houses would help look after the corpses during the wake, easing the burden on family members who were expected to keep vigil 24 hours a day.

“Breaking of Hell” Ceremony

The Chinese believe that when people die, they are transported to hell to be punished for bad deeds done when the person was alive. The Chinese also believe that hell comprises 18 levels with punishments increasing in severity as one descends from one level to the next.

The “breaking of hell” ceremony was performed by a Taoist priest after a person’s death to rescue the deceased from the horrors of hell by “lead[ing] him across the bridge that forms the link with heaven (kor tin khew)”.36 This would allow the dead to escape punishment and be reincarnated without suffering. In Cantonese, this is called phor tei yuk (to conquer hell).

This was an elaborate open-air ceremony lasting several hours. The ceremony would begin around 7.30pm and end around 11pm. A fire would be set up in the middle of the road with 18 roof tiles placed in a circle on the ground. Each tile represented one of the 18 levels of hell. As the ceremony began, the priest would recite some Cantonese incantations, then jump over the fire and break one tile by stepping on it, repeating the entire sequence until all 18 tiles were broken. This signified that all 18 levels of hell had been invaded and that the rescue attempt was a success. Occasionally, during the ceremony, the priest would also take a mouthful of spirit and blow it out onto the fire to create a more dramatic spectacle.37

The priest would convey a simple message through the incantations, asking the spirits to assist the dead in his or her journey through the afterlife.

Family members would observe the ceremony and carry out various funeral rituals as directed by the priest, such as walking around the coffin in circles to seek protection for the dead in hell and burn joss paper as offerings to the dead. Wealthier families also gave burnt offerings in the form of paper mansions, servants, television sets, and cars as a show of filial piety, as they believed that these riches would follow the dead to hell and make life in the underworld more comfortable.38

As there were several death houses along Sago Lane during the 1930s, this ceremony was a common sight at night and a draw for “overseas visitors with a morbid interest in the dead and dying”.39

Even during the daytime, Sago Lane would be abuzz with activity, and visitors would be greeted with:

Auxiliary Shops

Complementing these death houses, neighbouring shops on Sago Lane, Temple Street, Pagoda Street and Trengganu Street sold funerary goods such as coffins, joss paper, joss sticks, candles and sou yi (lifelong clothing) for the bereaved family members to wear during the obligatory three-year mourning period. These clothes were soaked in a large earthenware jar to dye them black.40 Other businesses provided professional services of a funeral troupe, “embalming services, sold flower wreaths, prepared the wake, and made paper effigies of houses, cars, wheelchairs, and even Malayan Airways planes”.41 Late-night food stalls on Sago Lane and at the intersection of Banda Street and Carpenter Street catered to the supper needs of family members and wake attendants who were supposed to keep watch over the corpse throughout the night. Several shophouses along Sago Lane also operated as brothels and restaurants.42

The synergistic co-location of funeral establishments, allied trades and death houses created a specialised hub within Chinatown where funeral activities were conveniently and expediently arranged.

Demise of Death Houses

In 1958, the Singapore City Council held a debate to discuss whether the death houses at Sago Lane should be moved to rural areas for health and safety reasons due to the fire hazards posed when joss paper was burnt as offerings for the dead. Another reason was the noise and air pollution generated as well as nuisance created by the death houses to residents nearby.43 The health committee also recommended that the death houses be given a year’s notice to move out of the city and to stop issuing new licences for Sick Receiving Houses.44 The health committee’s recommendations were overturned after a vote was called by the City Council as members believed that “Sick Receiving Houses [were] a social necessity in the Sago Lane area”.45

In the early 1960s, death houses garnered negative publicity overseas and were forbidden from renting out “bed-space to the sick and old waiting to die”.46 Death houses were eventually banned in 1961.47 The remaining two houses at Sago Lane were converted into full-fledged funeral parlours. After the ban came into effect, the death houses-turned-funeral parlours and auxiliary shops were moved to Sin Ming Road and Geylang Bahru industrial estate, paying a concession rental of $375 per month.48

Part of Sago Lane was demolished for the construction of Kreta Ayer Complex in 1972. Due to urban redevelopment, shophouses along one side of Sago Lane were demolished in 1975 and high-rise “apartments with shops and community centre on the lower floors”49 were erected in their place. “The remaining shophouses were cleared and a 3-storey market and food centre with a residential tower block was built, leaving only a pedestrian walkway along a stretch of Sago Lane.”50 However, in an effort to revive the old Chinatown atmosphere and spirit, the Singapore Tourism Board preserved the few remaining old shophouses along Sago Lane51 which now operate as souvenir shops and eateries.52

The land in front of Sago Street and Sago Lane, bound by South Bridge Road and Banda Street, was left vacant until May 2005 when the construction of the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum commenced, at the invitation of the Singapore Tourism Board. The temple was officially opened two years later on 30 May 2007. The $62 million, seven-storey temple and museum occupies an area of just under 3,000 square metres.53

REFERENCES

The Street of the Houses of Dead. (1948, September 25). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

City Council to debate death houses. (1958, September 17). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Councillors: We are ready to go any time. (1958, September 19). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Death houses now refuse the living. (1962, September 11). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

‘Dead quiet’ business… (1975, October 23). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Boon, C.T. (1950, September 3). Chinatown speakers. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum. (n.d.). History of Sago Lane. Retrieved from Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum website.

Chan, B. (2007, May 19). Parade, Chinatown light-up to mark Vesak. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chan, H.C. (1999). Death houses and hospices an autopsy of Sago Lane [Unpublished honours degree dissertation]. Singapore: National University of Singapore. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Chan, K.S. (1999, March 13). No love lost for the old ‘street of the dead’. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chan, K.S. (2001, October 15). Paper chase in afterlife. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chan, K.S. (2002, February 4). Take me to watercart street. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chan, Y. (2012). Sago to Go – Our Pioneering Manufacturing Export. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Chua, C.H.J. (Interviewer). (1999, May 21). Oral history interview with Chua Chye Chua (MP3 recording no. 002140/23/01]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Eliiot, A. (1950, August 13). How high is a man’s soul? The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Goh, G. (1998, June 3). Take me to The Great Horse Way. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Haifeez, M. (1978). Reminiscent Singapore. New York: Vantage Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 HAI)

Keye, A.W. (2004). Chinatown: Different exposures. Singapore: Fashion21. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 KEY)

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2003, June 22). Oral history interview with Lo Hong Ling [MP3 recording no. 002770/10/19]. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2003, August 5). Oral history interview with Lo Hong Ling [MP3 recording no. 002770/19/19]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Lowe-Ismail, G. (1998). Chinatown memories. Singapore: Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LOW)

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Toponymics: A study of Singapore street names. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV)

Singapore City Council. (1958). Minutes of the Proceedings of the City Council of Singapore, September 17 (pp. 4–5). [Microfilm: R0031457]. Singapore: The Council.

Sit, Y.F. (1983). Tales of Chinatown. Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 070.44939 SIT)

Suan, K.L. (1971, June 6). Only thing down is cost of dying… The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, A., & Quek, E. (2007, May 31). Colourful start to Vesak Day festivities. The Straits Times, p. 67. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Thulaja, N.R. (2016). Sago Lane. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.

Tyers, R.K. (1993). Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then and now. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TYE)

Yeo, C. (Interviewer). (2007, August 22). Oral history interview with Ng Fook Kah [MP3 recording no. 003219/11/01]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Yeo, L.F. (Interviewer). (1999, October 18). Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok [MP3 recording no. 002209/23/19, 20]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

NOTES

-

Chan, 1999, p. 61. ↩

-

Savage and Yeoh, 2003, p. 337. ↩

-

Chan, 2012. ↩

-

Savage and Yeoh, 2003, p. 337. ↩

-

Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum, 2012. ↩

-

Lee, Oral history interview with Lo Hong Ling, 22 Jun 2003. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

Yeo, Oral history interview with Ng Fook Kah, 22 Aug 2007. ↩

-

Lee, Oral history interview with Lo Hong Ling, 22 Jun 2003. ↩

-

Yeo, Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok, 18 Oct 1999. ↩

-

Lee, Oral history interview with Lo Hong Ling, 22 Jun 2003. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

Chua, Oral history interview with Chua Chye Chua, 21 May 1999. ↩

-

Chua, Oral history interview with Chua Chye Chua, 21 May 1999. ↩

-

Chua, Oral history interview with Chua Chye Chua, 21 May 1999. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

Lee, Oral history interview with Lo Hong Ling, 5 Aug 2003. ↩

-

Chua, Oral history interview with Chua Chye Chua, 21 May 1999. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 13 Mar 1999, p. 7. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

Chua, Oral history interview with Chua Chye Chua, 21 May 1999. ↩

-

Yeo, Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok, 18 Oct 1999. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Sep 1948, p. 4. ↩

-

Yeo, Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok, 18 Oct 1999. ↩

-

Yeo, Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok, 18 Oct 1999. ↩

-

Yeo, Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok, 18 Oct 1999. ↩

-

Yeo, Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok, 18 Oct 1999. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 13 Mar 1999, p. 7. ↩

-

Lowe-Ismail, 1998, p. 20. ↩

-

Lowe-Ismail, 1998, p. 20. ↩

-

Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum, 2012. ↩

-

Singapore City Council, 1958, pp. 4–5. ↩

-

Singapore City Council, 1958, pp. 4–5. ↩

-

Singapore City Council, 1958, pp. 4–5. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 6 Jun 1971, p. 10. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Oct 1975, p. 3. ↩

-

Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum, 2012. ↩

-

Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum, 2012. ↩