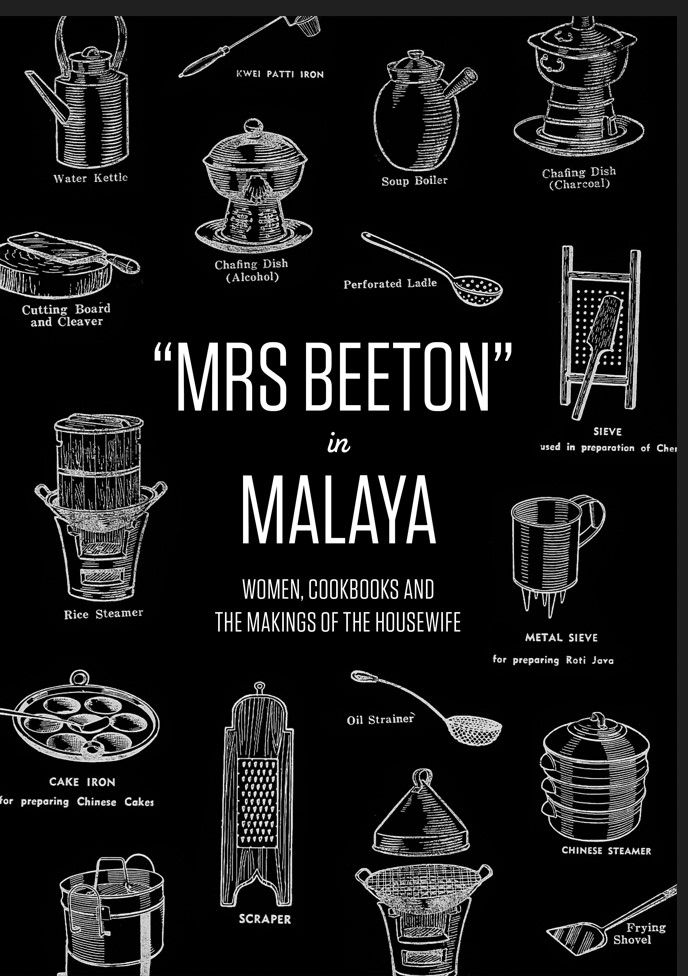

“Mrs Beeton” in Malaya: Women, Cookbooks and the Makings of the Housewife

Cookbooks offer interesting insights into the oft-overlooked domestic space of British Malaya, shedding light on how women saw themselves and how feminine ideals from the West were propagated in the colonial era.

Cookbooks, pamphlets, newspapers, domestic manuals and the like are rich sources of recipes, diet and nutrition advice as well as kitchen anecdotes and trivia. The non-literary and utilitarian nature of these writings belies their narrative potential as texts that contain rich socio-historical material on food-related culture. Despite their seeming inconsequentiality, details on everyday cooking and eating provide clues to wider debates about national, colonial, postcolonial, class, race and gender politics. English-language cookery texts published in early 20th century British Malaya provide a discursive space where women – whether writing, reading or practising the culinary arts – can participate in fashioning the feminine ideal.

Regarded as the paragon of progressive womanhood in the history of British domesticity, the legacy of Isabella Beeton’s magnum opus, Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), refigures Malayan cookery texts beyond the parochial, suggesting the influence of domestic discourses from Victorian England. Cookbooks reproduce dominant gendered ideologies as “explicit emblems of women’s relegation to the domestic sphere – the world of the home”.1 Yet boundaries shift and blur when these texts also demonstrate how women, ostensibly acting in their traditional capacities as housekeeper and caregiver, could influence the well-being of the family, the wider community and beyond.

This essay examines individuals in Malaya who were privileged enough to have received English-language education, who saw the value of penning down what they knew and who possessed the wherewithal to publish their writings. The primary focus is English-language cookbooks, largely due to the relative paucity of extant vernacular cookery texts published in the same period.

The Recipe Book and Its Implications

A recipe book may seem unique to the sociocultural context in which it was written and published, but it speaks across time when it borrows from earlier works and draws on the conventions of the genre. In contextualising the recipe book within the history of British publishing, Margaret Beetham said: “The systematic reproduction of cooking instructions in commercial forms of print was symptomatic of a much wider process by which oral knowledges [sic] were gradually superseded by print.”2 Instructions on food preparation appeared as part of general household advice in printed books of “receipts” that predated the 19th century as well as in magazines and manuals that increasingly targeted a middle-class female readership since the 1850s.3

Published in 1861, Beeton’s Book of Household Management was instrumental to the birth of the recipe book as a popular print genre by the end of the century.4 Its subsequent publishing history contributed to the transformation of cookery into a subject with its own distinct cultural form. The recipe book thus added to an existing body of writing that mapped the domestic sphere and exposed the otherwise hidden labour performed by women. By instructing women on their expected behaviour and responsibilities in the home, these texts reified and affirmed the assumed conjunction between femininity and domesticity.

Beeton’s seminal work was typical of the general household manual of the time: it provided an array of advice, anecdotes, trivia, historical notes and other information usually of tangential relevance to the recipes being discussed.5 As Beeton herself acknowledged in the preface of the book, she had obtained the bulk of the material from readers’ contributions to the first successful middle-class women’s magazine in Britain, The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, published by Isabella’s husband, Samuel Beeton.

Her volume nevertheless contained an innovation that has since become a defining characteristic of the recipe book. Beeton “codified a previously chaotic body of knowledge”6 by introducing a standard format for organising and presenting recipes in a systematic way. This includes the listing of ingredients (by weight) followed by the method of preparation and estimated cost for a given recipe, arranging recipes in alphabetical order and providing an index to facilitate the location of information within the dense text.7 Furthermore, cooking methods were elaborated in a straightforward and impersonal style.

In this way, Beeton’s volume delineated the practicalities of running the home with unprecedented clarity and brevity. This paved the way for “a science of domestic management, one that could be systematically taught through textbooks”.8 As a result, Beeton not only articulated the responsibilities and expected conduct of the middle-class woman as the mistress of the household, but also provided detailed and precise instructions for the fulfilment of her role. Therein lies the “public normalising impulse”9 of the cookbook, among other household manuals, in setting the criteria for the proper management of the kitchen/domestic sphere and as the arbiter of consumption.

“Mrs Beeton” Arrives in Malaya

The success of Beeton’s book lies in its ability to explicitly address the particular cultural anxieties of its intended audience by offering a feminine ideal to which women could aspire. Decades after its initial publication, “Mrs Beeton” still spoke with authority and relevance to a new generation of Englishwomen setting up their homes in the far-flung lands of the British Empire.

By the early 20th century, extracts of the original work had been published in booklet form under the name of “Mrs Beeton”. Nearly all such spin-offs were recipe or cookery books, thus cementing the association between “Mrs Beeton” and cooking instruction.10 “I used to spend the mornings reading, sewing, and teaching myself to cook [emphasis added] out of Mrs Beeton,” recalled “V. St. J.” of her days as a young expatriate wife residing in the ulu [remote] hinterlands of the Malayan peninsula.11

In Malaya, the recipe book became indispensable to the newly arrived European wife, or memsahib12 (often truncated as mem), as a guide to reproducing home – or rather the familiar taste of it – abroad. More than a means for educating the self, the recipe book was used to instruct servants where, for example, “with the aid of ‘Mrs Beeton’ and a little tact and courage [the mem] may convert a bad or indifferent cook into a quite presentable exponent of the art”.13

Beyond the use of “Mrs Beeton” books in colonial homes, the “presence” of “Mrs Beeton” in Malaya alludes to the translation of feminine domesticity from Victorian England to the Malayan context in the form of texts that deal with cookery. While it is admittedly difficult to determine the extent of direct influence that Beeton’s volume had on Malayan cookery texts, “Mrs Beeton”, as a symbol of domesticity, an embodiment of the multilayered nature and discursive potential of the recipe book, as “a practical manual, and a method for scientific education and a fantasy text”,14 offer approaches to interpreting the recipe books of Malaya.

The Myth of the Lazy Mem

“The housewives who come out to Malaya from Europe may be divided into two distinct groups. The first is composed of dilettante wives, who leave everything pertaining to culinary matters and the control of their households entirely to their native staffs, and who, consequently, are forever [sic] complaining of the lack of flavour and nourishment of the food in Malaya and the absence of training and honesty of those who serve them. The other group consists of those who take an intelligent interest in the supplies and preparation of food and all which affects the comfort of their homes. […] Has it not been said, ‘Home-making hearts are happiest’.”

The above observation made by an experienced mem implies that the fundamental purpose – in fact, the very happiness – of the English wife in Malaya resides in the conscientious care of the home. The establishment of the English home in colonial territories led to a “physical repositioning of the hitherto private into […] the most public of realms – the British empire”.15 As will be subsequently explained, this intersection of domesticity with imperial power provided an avenue through which European women could advance the work of the British Empire in ways that were consistent with prevailing gender roles.

By maintaining domestic standards, wives were regarded as a civilising influence that preserved colonial culture and prestige against the perceived degenerative tendencies of tropical living.16 The upkeep of the colonial household heavily depended upon the labour of a racially diverse team of servants. The responsibility of overseeing the staff fell to the mem, whose conduct and successful administration of the household mirrored and reproduced the unequal relations between coloniser and colonised.17

The domestic role of the European wife thus carried a political significance in reinforcing colonial dominance within and without. With reference to the earlier comments of E.M.M., it was the availability of domestic help – especially competent and reliable ones – that minimised mem’s involvement in the actual work of cooking and cleaning.18 As a British resident in the 1930s noted, “Flocks of silent servants see to every detail; even the housewife has only one duty, to have an interview with Cookie [the cook] once a day.”19 In light of this, colonial cookery books were part of the “cultural technologies of rule”20 that guided the mem in her civilising mission and supervisory role. The domestic and imperial power of the British housewife was predicated not only on her knowledge of homemaking in colonial settings but also her ability to manage the servants.21

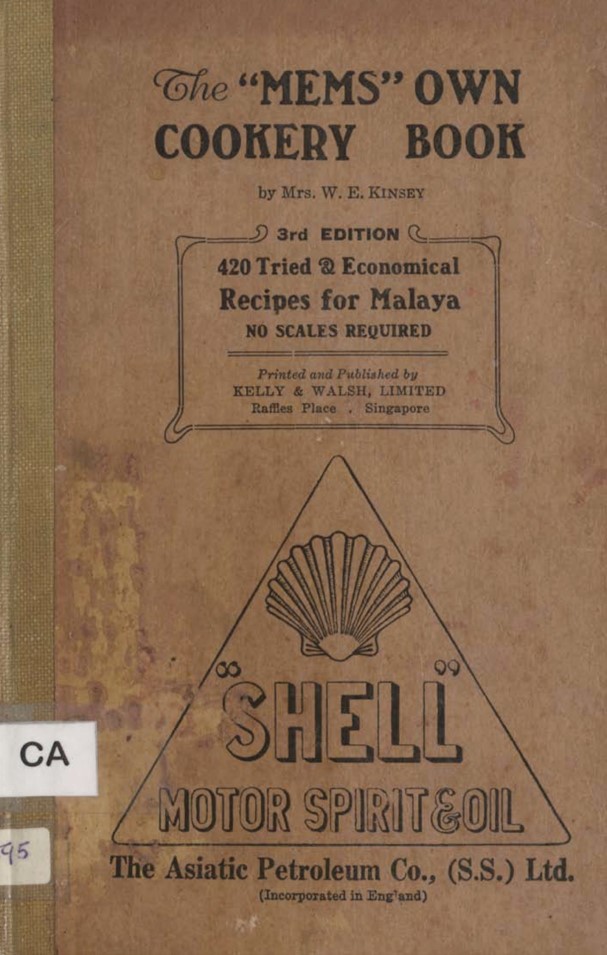

First published in 1920, W.E. Kinsey’s The “Mems” Own Cookery Book22 (“Mems” Own) would have been much favoured by the “other group” of European housewives who took “an intelligent interest” in domestic affairs. Kinsey expressed that the book aims “to help those ‘mems’ who are keen on taking advantage of the possibilities of catering in this country”.23 Boasting 420 “tried and economical” recipes based on “FIVE Years [sic] […] practical application by the writer”, Kinsey clearly presented herself as an authority on colonial cooking. As if to allay any doubts, the preface concludes with an “IMPORTANT [sic]” note declaring that “ALL [sic] these recipes have been TRIED AND PROVED [sic] by the writer in Seremban, Negri Sembilan, F. M. S.”. Kinsey thus appealed to aspiring mems with the prospect of efficient domestic management made easier through failsafe recipes – “not one is beyond the resources of the average kitchen even in the absence of scales”.24

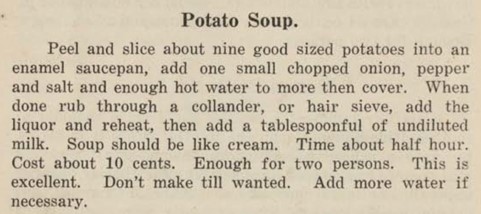

The instruction for each dish weaves together ingredients, method and personal opinion in a single paragraph. No doubt a cookery book, “Mems” Own, however, did not adopt the Beeton format, which demonstrates how older styles of recipe writing continued alongside newer conventions. Reflecting the hybrid nature of colonial cuisine, the recipes cover quintessential English fare as well as French and Anglo-Indian dishes familiar to the British palate. The mem is therefore able to overcome “the extreme difficulty of fixing the menu for the next day […] by constructing a roster of courses”25 from Kinsey’s recipes. Then, book in hand, the mem “can either prepare herself or instruct ‘cookie’ in a host of dishes which should do a great deal to remove the charge of monotony which is sometimes levelled at food in Malaya”.26

Most of the recipes state the market price of the ingredients, the total cost of the dish and the number of servings. For example, the recipe for Bone Soup states: “Ten cents worth of good beef bones (about two katties) […] Cost about 16 cents [in total]. Enough for two or three persons.”27 By placing such information at the mem’s disposal, Kinsey hoped that her book would “assist to combat the pernicious policy of the native cooks who not only overcharge for local commodities, but generally will not produce them, or attempt to raise non-existent difficulties”.28

The colonial cookbook was an administrative text that conceivably helped the mem to regulate the daily functioning of the kitchen/domestic sphere. In practice, the establishment of imperial domesticity was marked by negotiation as opposed to the outright imposition of the mem’s will.29 The colonial diet depended not only on the cook’s familiarity with local ingredients and how they should be prepared, but also on the cook’s intimate knowledge of his or her employers’ preferences.

Mary Heathcott recounted an episode where, tired of the usual ikan merah (red snapper) and pomfret, her attempt to introduce a new fish encountered resistance from her cook, Ah Lee, who protested, “Fish no good”, and even questioned, “Why you not buy ikan merah?” While Ah Lee eventually cooked the fish for lunch, Heathcott “had the ground undermined beneath [her] feet” by her family’s refusal to eat the fish on account that “The cook knows. It’s probably bad […] and we’ll all look much sillier with fish poisoning.”30 Heathcott pronounced this incident a “Complete rout of Mem”.31 In this particular instance, mem had the last laugh as she later discovers from Malayan Fish and How to Cook Them,32 that the fish was, in fact, edible and of “good flavour”.

The Domestication of Malayan Foods

Cookbooks reveal the processes through which the colonial knowledge of Malaya was constructed. The inclusion of recipes for rundang (a spicy meat stew; or rendang) and satai (skewered, grilled meat; or satay) in “Mems” Own introduced and explicated the preparation and consumption of otherwise unfamiliar local foods, consequently normalising their presence within the colonial diet.

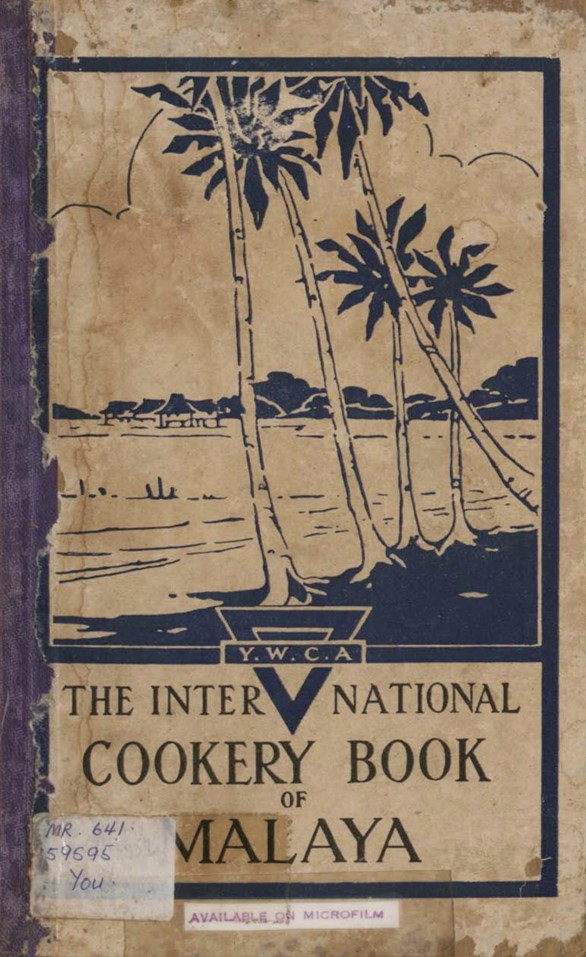

Published in 1935, the second edition of the Y.W.C.A. International Cookery Book of Malaya by Mrs R.E. Holttum and Mrs T.W. Hinch differs markedly from Kinsey’s work in ways that signal the extent to which food and nutrition in Malaya had become a subject of intellectual and practical study. As a compilation of “the numerous recipes used in the international cooking lessons conducted […] by the [Young Women’s Christian] Association”,33 the volume is perhaps more closely identified with the teaching of domestic science than “Mems” Own.

In contrast to the almost exclusive focus on recipes in Kinsey’s book, the YWCA volume offers comprehensive guidance that covers meal planning, purchase of ingredients and other preparatory tasks preliminary to the actual cooking. Most sections are prefaced by general remarks on cooking methods and principles; for example, a brief overview on “How to make soup”34 precedes the section on soup recipes. The ingredients are listed separately from the cooking process where each step is relayed plainly and succinctly.

Placing the knowledge of local foods and the colonial diet on a scientific footing, the YWCA cookbook introduces the concept of “food values”, in which an individual’s energy and nutritional requirements dictate the basis for efficient and healthful eating in the tropics.35 This is complemented by a “chemical analyses of Malayan foods”, in which over 90 local products, including blachan (dried shrimp paste; or belacan), shark’s fin and edible bird’s nest, are reduced to their caloric content and nutritional composition.36

This unravelling of the exotic and unknown is further augmented by a glossary of Malay and English names for local market produce. Moreover, the recipes are divided into European, Chinese, Indian and Malay sections – corresponding to the colonial scheme of racial classification. As knowledge is integral to power, cookbooks are conceivably part of colonialist attempts to bolster a coherent understanding of Malaya through mastery over “even the most mundane aspects of imperial life”.37 The women who compiled these cookbooks are thus implicated in the making of the empire.

In her study of European wives in British Malaya, Janice Brownfoot notes that mems, freed from household chores, devoted their time to charitable and voluntary welfare work through all female organisations such as the YWCA. Brownfoot argues that the formation of these groups indicated women’s recognition of shared feminine interests that cut across racial and class lines.38 Instructing non-European women on cookery and other domestic skills allowed the mem to mobilise her knowledge towards uplifting the welfare of the colonial populace, thus exercising her civilising influence. Brownfoot describes the YWCA as at once both conservative and progressive because, despite its emphasis on the importance of traditional domestic duties and feminine skills, it exposed Asian women to Western ideas and methods.39

The YWCA cookbook not only attests to the work accomplished by the association, but also uncovers the kind of community network and collaboration that made such an assemblage of information possible. While “Mems” Own was based on the experience of an individual housewife, the original YWCA cookbook and its subsequent editions were put together with contributions and feedback from “readers of all nationalities”.40

In fact, the preface of the book acknowledges the “help of Chinese and Indian friends”41 whose names are duly appended to their respective recipes. The impression of egalitarian participation and cultural exchange is tempered by how it was, after all, a pair of expatriate wives who undertook the critical work of collecting, editing, organising, representing and, finally, returning the information in cookbook form to Malaya, as a gift from its “civiliser”.42

Becoming “Mrs Beeton” of Malaya

“Perhaps one day some lady living in Malaya will give her time and patience to research in Malayan cookery, and if she has a flair for cooking herself, be able to write down the information in those measures and method-descriptions that we know as recipes.”

Holttum and Hinch would have been pleased to learn of Che Azizah binte Ja’affar who in November 1950 was “compiling a cookery book with international recipes giving exact quantities of all ingredients for each dish”.43 Che Azizah was “very interested in cookery” and sought to give traditional Malay dishes “a new twist” with the infusion of Western techniques where, for example, she baked otalt-otalt (a concoction of fish paste and spices; or otak-otak) in a pastry case instead of coconut leaves.44 Desiring “more education […] and more economic independence”45 for Malay women, she ran a domestic science school in Johor and was personally involved in “teaching her pupils how to run their homes on modern, hygienic lines, [and] how to provide meals which are delicious and nutritious”.46 For her efforts, Che Azizah was described as “perhaps […] another Mrs Beeton [for she was] not only a good cook but a very progressively minded woman as well”.47

It is intriguing how Asian women, particularly those who were trained in domestic science and became its proponents, could be viewed as having adopted attributes associated with Western notions of feminine modernity. “MRS BEETON’ IN ACTION [sic]” ran the caption of a photograph in The Straits Times showing Esther Chen, author of two books on Chinese cooking, teaching in the kitchen of the YWCA in 1954. The writer highlighted the presence of several European women in the beginners’ class, though “no European woman has yet graduated to the advanced classes”.48

Che Azizah was one among several who gained recognition for their culinary expertise to the extent of being dubbed “Mrs Beeton”, which suggests comparability with those whom they emulated. Such cultural appropriation symbolised both submission and subversion.49 Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery but successful mimicry at the same time undermined the myth of colonial superiority.50

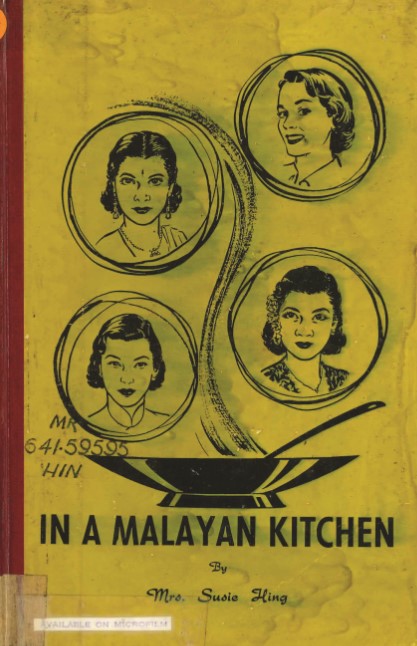

The cookbook offered Asian women, as it did for European women, “a textual apparatus which enabled […] some claim to legitimation and public spaces”.51 Published in 1956, Susie Hing’s In a Malayan Kitchen provides recipes for “dishes as varied and as colourful as our Malayan people”,52 thus expressing a nascent national consciousness at a time of decolonisation and political awakening.

In her introduction to the book, Hing casts ethnic pluralism in a positive light as “one of the most attractive things about living in Malaya […], affording as it does many opportunities to absorb something from each and everyone”.53 The variety of food is not only a boon to those interested in cookery but, more importantly, it “provides […] opportunities through mankind’s common factor, the appetite, for barriers to be broken down and understanding to develop”.54

Unlike the YWCA volume, the recipes in Hing’s book are presented together in one chapter regardless of their ethnic affiliations. For example, the recipes for Java nasi goreng (fried rice) and Cantonese-style fried rice are listed in the same category, “Dishes”, in the index. In fact, both recipes are featured on the same page. This manner of mapping the culinary diversity of Malaya encourages the reader to readily perceive commonalities between the cuisine of her community and that of others. Hing’s cookbook thus points to how women, through the food they prepare, create opportunities that they, their families and, by extension, their communities, could experience – albeit superficially – the everyday lives of fellow Malayans.

Food for Thought

As shown, cookbooks can be read beyond their literal content to explore meanings embedded in the structure, tone, language and other aspects of textuality. The cookbook has emerged as a cultural form that not only reaffirmed the association between domesticity and femininity but is also identified with female self-expression. The cookbook is an amalgamation of ideas and inspirations derived from women (and men) of different generations, ethnicities and even social strata as recipes are recurrently exchanged and reproduced.

Insofar as cookbooks appear to document reality, they possess an element of fantasy in prescribing a feminine ideal that may not concur with the real-life experiences of its readers. Cookbooks allow women to maintain a self-image that conforms to convention, while at the same time offer an opportunity to envision themselves in positions of authority and influence. Even if women merely perused the recipes and daydreamed about cooking, cookbooks nonetheless have the potential to transform how women perceived themselves and their identities.55

Janice Loo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library Content and Services division. She graduated with a BA (Hons) in Southeast Asian Studies with a second major in History from the National University of Singapore in 2011. She keeps a casual record of food-related discoveries from the library's collections at eatarchive.tumblr.com.

Janice Loo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library Content and Services division. She graduated with a BA (Hons) in Southeast Asian Studies with a second major in History from the National University of Singapore in 2011. She keeps a casual record of food-related discoveries from the library's collections at eatarchive.tumblr.com.

REFERENCES

Books

Hing, S. (1956). In a Malayan kitchen. Singapore: Mun Seong Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 HIN)

Holttum, R.E., & Hinch, T.W. (Eds.). (1935). International cookery book of Malaya. [Malaya]: YWCA of Malaya. (Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 YOU; Microfilm no.: NL16675)

Kinsey, W.E. (1929). The mem’s own cookery book: 420 tried and economical recipes for Malaya. Singapore: Kelly & Walsh. (Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 KIN; Microfilm no.: NL9852)

Leong-Salobir, C. (2011). Food culture in colonial Asia: A taste of empire. London: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 394.12095 LEO)

MacCallum Scott, J.H. (1939). Eastern journey. London: Travel Book Club. (Call no.: RCLOS 959 MAC)

Articles and chapters in books

Beetham, M. (2010). Of recipe books and reading in the nineteenth century: Mrs Beeton and her cultural consequences (pp. 15–30). In J. Floyd., & L. Forster (Eds.), The recipe reader: Narratives, contexts, traditions. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Bhabha, H. (1997). Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse (pp. 152–162). In F. Cooper & A.L. Stoler (Eds.). Tensions of empire: Colonial cultures in a bourgeois world. Berkeley: University of California Press. (Call no.: RUBC 909.8 COO)

Blunt, A. (1999). Imperial geographies of home: British domesticity in India, 1886–1925. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 24 (4), 421–440. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Brownfoot, J.N. (1984). Memsahibs in colonial Malaya: A study of European wives in a British colony and protectorate 1900–1940 (pp. 186–210). In H. Callan & S. Ardener (Eds.). The incorporated wife. London: Croom Helm. (Not available in NLB holdings)

George, R.M. (1993–1994, Winter). Homes in the empire, empires in the home. Cultural Critique, 26, 95–127. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Newlyn, A.K. (1999, Fall). Challenging contemporary narrative theory: The alternative textual strategies of nineteenth-century manuscript cookbooks. Journal of American Culture, 22 (3), 35–47. Retrieved from Wiley Online website.

Procida, M. (2003, Summer). Feeding the imperial appetite: Imperial knowledge and Anglo-Indian domesticity. Journal of Women’s History, 15 (2), 123–149. Retrieved from ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website.

Tobias, S.M. (1998). Early American cookbooks as cultural artifacts. Papers on Language & Literature, 34 (1), 3–18. Retrieved from ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website.

Zlotnick, S. (1996). Domesticating imperialism: Curry and cookbooks in Victorian England. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 16 (2/3), 51–68. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Newspapers

“Cookie”. (1929, October 16). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

E.M.M. (1933, April 23). The housewives of Malaya. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Heathcott, M. (1941, August 22). Fish on the menu need not be ikan merah. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

‘Mrs Beeton’ in action. (1954, May 6). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

V. St. J. (1938, March 6). I return to Malaya as a bride. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Newlyn, A.K. (1999, Fall). Challenging contemporary narrative theory: The alternative textual strategies of nineteenth-century manuscript cookbooks. Journal of American Culture, 22 (3), 35–47. Retrieved from Wiley Online website. ↩

-

Beetham, M. (2010). Of recipe books and reading in the nineteenth century: Mrs Beeton and her cultural consequences (pp. 15–30). In J. Floyd., & L. Forster (Eds.), The recipe reader: Narratives, contexts, traditions. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Beetham, 2010, pp. 16–17, 20. ↩

-

Beetham, 2010, p. 17. ↩

-

Beetham, 2010, p. 18. ↩

-

Beetham, 2010, p. 21. ↩

-

Beetham, 2010, p. 21. ↩

-

Beetham, 2010, p. 22. ↩

-

Tobias, S.M. (1998). Early American cookbooks as cultural artifacts. Papers on Language & Literature, 34 (1), 3–18, p. 9. Retrieved from ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

See, for example, Beeton, I., & Baker, G. (2012). Mrs Beeton’s cakes & bakes. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. (Call no.: 641.865 BEE); Beeton, I., & Baker, G. (2012). Mrs Beeton puddings. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. (Call no.: 641.865 BEE); Beeton, I., & Baker, G. (2012). Mrs Beeton classic meat dishes. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. (Call no.: 641.865 BEE). Available at Public Libraries. ↩

-

V. St. J. (1938, March 6). I return to Malaya as a bride. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Europeans wives were collectively called memsahibs, a generic term borrowed from India that literally means “Madam Boss”. ↩

-

“Cookie”. (1929, October 16). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Beetham, 2010, p. 29. ↩

-

George, R.M. (1993–1994, Winter). Homes in the empire, empires in the home. Cultural Critique, 26, 95–127, p. 99. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Brownfoot, J.N. (1984). Memsahibs in colonial Malaya: A study of European wives in a British colony and protectorate 1900–1940 (pp. 186–190). In H. Callan & S. Ardener (Eds.). The incorporated wife. London: Croom Helm. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Blunt, A. (1999). Imperial geographies of home: British domesticity in India, 1886–1925. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 24 (4), 421–440, 429–431. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Brownfoot, 1984, p. 196. ↩

-

MacCallum Scott, J.H. (1939). Eastern journey (p. 14). London: Travel Book Club. (Call no.: RCLOS 959 MAC) ↩

-

Dirks, N.B. (1996). Foreword. In B. Cohn, Colonialism and its forms of knowledge: The British in India (p. ix). New Jersey: Princeton University Press. (Call no.: R 954 COH), quoted in Procida, M. (2003). Feeding the imperial appetite: Imperial knowledge and Anglo-Indian domesticity. Journal of Women’s History, 15 (2), 123–149, p. 138. Retrieved from ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Blunt, 1999, p. 431. ↩

-

For a description of the content and aspects of food history, see Tan, B. (2011). Malayan cookery books. BiblioAsia, 7 (3), 30–34. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Kinsey, W.E. (1929). The mem’s own cookery book: 420 tried and economical recipes for Malaya (Preface). Singapore: Kelly & Walsh. (Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 KIN; Microfilm no.: NL9852) ↩

-

The literary page – new books reviewed. (1930, January 31). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Some new books. (1922, May 6). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 30 Jan 1931, p. 17. ↩

-

Leong-Salobir, C. (2011). Food culture in colonial Asia: A taste of empire (p. 12). London: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 394.12095 LEO) ↩

-

Heathcott, M. (1941, August 22). Fish on the menu need not be ikan merah. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 22 Aug 1941, p. 5. ↩

-

Compiled by Assistant Director of Fisheries, D.W. Le Mare, “Malayan Fish and How to Cook Them” is a pamphlet issued by the Department of Information and Publicity to encourage the consumption of local food fishes. ↩

-

Holttum, R.E., & Hinch, T.W. (Eds.). (1935). International cookery book of Malaya (p. 5). [Malaya]: YWCA of Malaya. (Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 YOU; Microfilm no.: NL16675) ↩

-

Holttum & HInch, 1935, p. 49. ↩

-

Holttum & HInch, 1935, pp. 7–10. ↩

-

Holttum & HInch, 1935, pp. 13–20. ↩

-

Procida, Summer 2003, p. 138. ↩

-

Brownfoot, 1984, p. 199. ↩

-

Brownfoot, 1984, p. 200. ↩

-

Holttum & HInch, 1935, p. 5. ↩

-

The editors expressed regret that “so small a section should be presented […] about the cookery of the native inhabitants of Malaya”. The few recipes contained in the “Malay Section: were contributed by M.C. Murray of the Malay Girls’ School in Melaka, Ishak, a senior fishery officer in Singapore, and Miss M.A. Bixton. ↩

-

Zlotnick, S. (1996). Domesticating imperialism: Curry and cookbooks in Victorian England. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 16 (2–3), 51–68, p. 64. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Heathcott, M. (1950, November 28). Singapore revisited. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 28 Nov 1950, p. 8. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 28 Nov 1950, p. 8. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 28 Nov 1950, p. 8. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 28 Nov 1950, p. 8. ↩

-

‘Mrs Beeton’ in action. (1954, May 6). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Procida, Summer 2003, p. 124. ↩

-

Homi Bhabha. (1997). Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse (pp. 152–162). In F. Cooper & A.L. Stoler (Eds.). Tensions of empire: Colonial cultures in a bourgeois world. Berkeley: University of California Press. (Call no.: RUBC 909.8 COO) ↩

-

Newlyn, Fall 1999, p. 37. ↩

-

Hing, S. (1956). In a Malayan kitchen (p. 7). Singapore: Mun Seong Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 HIN) ↩

-

For more on cookbooks as romance or “escapist” reading that allowed women to imagine themselves in different roles, see Bower, A.L. (2004, May). Romanced by cookbooks. Gastromonica: The Journal of Food and Culture, 4 (2), 35–42. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩