Hawkers: From Public Nuisance to National Icons

From bane of the government to boon of tourism, hawkers in Singapore have come a long way from the time they were viewed by government officials as progenitors of disorder and disease.

For one of the smallest countries in the world, Singapore has an enormous appetite. According to the annual MasterCard survey on consumer dining habits, Singaporeans were the biggest spenders for eating out in the Asia-Pacific region in 2012, with an average expenditure of $323 each month. This was an increase of nearly 25 percent from 2011.1 In addition, the great lengths that Singaporeans go to in search of the best or most authentic local dishes are testament to the nation’s obsession with food. They endure long queues, brave traffic jams and literally go the distance to satiate their taste buds. It is no wonder that the Singapore Tourism Board promotes the island as a food paradise, organising a series of annual food-related events, most notably the Singapore Food Festival, to boost tourist numbers.

Food and all matters culinary are an integral part of the Singaporean psyche. The city is a melting pot of multi-ethnic flavours and foods, with Malay, Indian and Chinese dishes making up the culinary landscape along with Peranakan and Eurasian cuisines. The island city is home to countless restaurants, but almost everyone agrees that the cheapest and most authentic fare is found in hawker centres.

Hawker centres, in Singapore parlance, are open-air complexes with stalls selling food at affordable prices. They are clean, accessible and are frequented by people from all walks of life. Most hawker stalls are family-run and serve one or two dishes that have been perfected over the years or prepared using family recipes passed down over the generations. As a result, hawker food is not only tasty but also rich in heritage.

However, the convenience of strolling into clean hawker centres for a delicious meal was unheard of in Singapore during the colonial period and early post-independence days. Instead, the norm was to eat by the roadside using dirty utensils and amid filthy conditions. How this was replaced by today’s hawker experience marked by good food and a clean eating environment is the result of a decades-long struggle between the government and hawkers.

A Public Nuisance

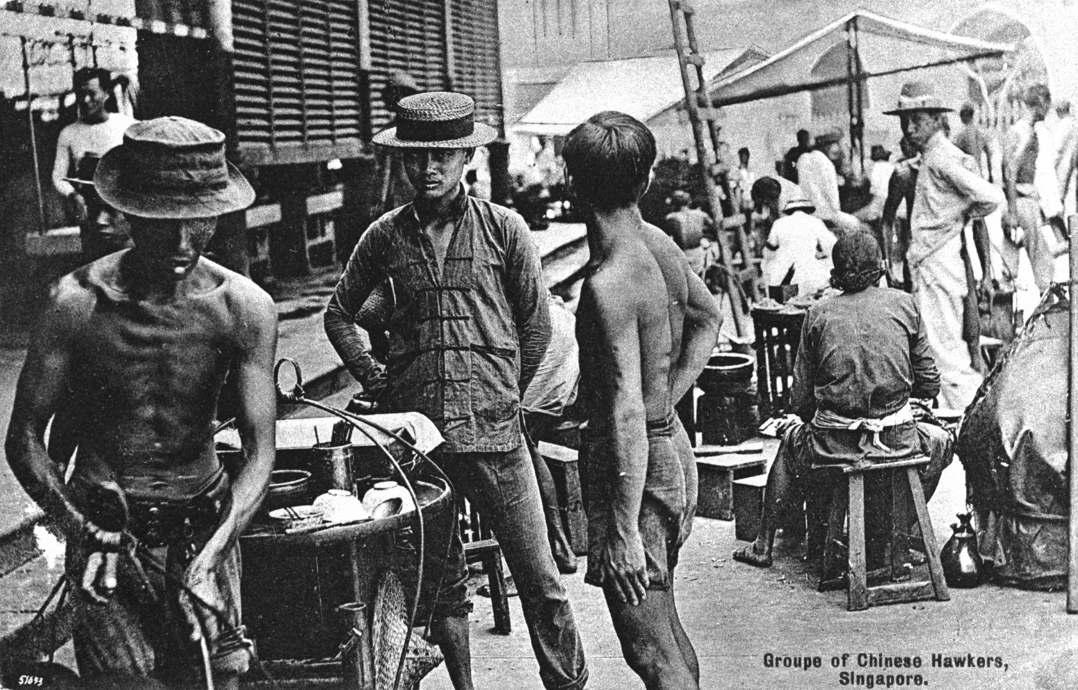

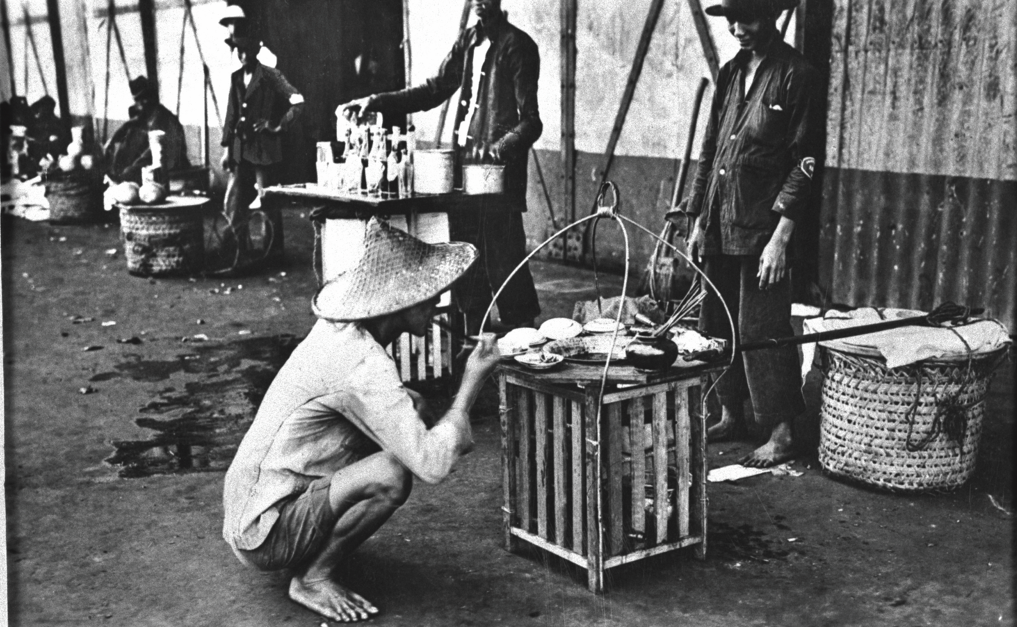

Peddling food has been part of Singapore’s heritage since the early colonial period. The hawker scene then was a vibrant one, marked by rows of stalls selling an endless selection of tasty and affordable local foods ranging from Malay kueh (cakes) to Chinese dishes. John Cameron in Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India (1865) noted this scene after his visit to Singapore in the 1860s:

“There is probably no city in the world with such a motley crowd of itinerant vendors of wares, fruits, cakes, vegetables. There are Malays, generally with fruit, Chinamen with a mixture of all sorts, and Klings with cakes and different kinds of nuts. Malays and Chinamen always use the shoulder-stick, having equally-balanced loads suspended at either end; the Klings, on the contrary, carry their wares on the head on trays. The travelling cook shops of the Chinese are probably the most extraordinary of the things that are carried about this way. They are suspended on one of the common shoulder-sticks, and consist of a box on one side and a basket on the other, the former containing a fire and small copper cauldron for soup, the latter loaded with rice, vermicelli, cakes, jellies, and condiments.”2

However, many considered hawkers, especially street hawkers, a public nuisance.3 They impeded both vehicular and foot traffic and made the streets rowdy and chaotic. The authorities also regarded hawkers as a source of public disorder, fuelling the activities of secret societies and street gangs by paying money in return for protection against intimidation and extortions from other secret societies and gangs.4

Perhaps the biggest concern was the threat that hawkers posed to public health. Hawkers were seen as potential agents for the outbreak of diseases such as cholera and typhoid due to their unhygienic practices. As reported by the Municipal Health Office in 1895, hawker food was “extremely liable to contamination” because they were exposed to the elements, and prepared over drains “containing all manner of filth, even human excreta”.5 This was exacerbated by infectious diseases carried by hawkers, using untreated water used to prepare the food, and the generally filthy conditions of the hawkers’ lodgings where ingredients were stored. One such store was described by the Sanitation Commission in 1907 as being “overrun with cockroaches and other vermin”.6

To resolve these issues, the colonial government decided that hawkers should be registered and licensed.7 This would confine hawkers to selected areas in the city and prevent them from encroaching into public spaces, while making it easier for authorities to monitor their hygiene practices and deal with any public disorder caused by them.8 A proposal for the legislation was made in 1903 but only materialised in 1906 as by-laws of the Municipal Ordinance. Unfortunately, the legislation lacked teeth and health officials did not have the full authority to shut down hawkers who violated the rule of law. In addition, the by-laws were only applicable to stall hawkers who operated at night. The rest of the hawker community, both daytime stall hawkers and itinerant hawkers, were still allowed to ply their trade freely during the day. Despite the various problems caused by hawkers, the colonial government still viewed the hawker trade as an essential part of society as it provided unemployed and unskilled workers with a source of livelihood, and the urban population with easy access to cheap meals.9 As a result, the government was reluctant to adopt a hard-line approach in suppressing them. Thus, the problems persisted and became so unbearable that it led to calls for the total abolition of hawkers.10

In response, the colonial government took further steps to control the growth of hawkers. First, they extended the registration and confinement of hawkers to include itinerant hawkers in 1915 and daytime stall hawkers in 1919. Second, the maximum number of hawkers’ licences issued from 1928 was capped at 6,000 to stem their growth. Third, the authorities started relocating licensed hawkers to specially built hawkers’ shelters.11 The first shelter – probably the precursor of the modern hawker centre – was built in 1922 at Finlayson Green. Thereafter, another five shelters were built at People’s Park, Balestier Road, Carnie Road, Telok Ayer Market and Queen Street.12

These shelters reduced the total number of hawkers from 11,249 in 1919 to 5,513 in 1929.13 But in reality, little progress was made in tackling hawker issues relating to hygiene and licensing; the efforts during the prewar years were summed up by the municipality as “a vain hope”.14 Indeed, as stated in the Report of the Hawker Question (1931), major roads in the town were still cluttered with some 4,000 unlicensed hawkers.15 By 1950, due to the lack of a decisive policy against unlicensed hawkers as well as the high unemployment rate during the postwar years, the number of such hawkers ballooned to 20,000.16 This magnified the various associated problems and once again led to calls for their complete eradication from the streets. Spearheading the condemnation was the Town Cleansing Department. It branded unlicensed hawkers as the “biggest single retarding factor” for their efforts in keeping the city clean.17 Shophouse owners, particularly coffee shops and food shops, were also unhappy with the unlicensed hawkers. The owners complained that they faced unfair competition from the unlicensed hawkers because the latter could operate at lower costs without paying rent or licence fees, and would deliberately set up stalls near the entrance or opposite their shops.18

Wrestling with the Hawker Problem

To prevent the hawker problem from escalating, a 10-member Hawker Inquiry Commission was set up in April 1950 to investigate the social, economic and health issues caused by unlicensed hawkers and to recommend policies to resolve them.19 In its final report released in September 1950, the commission concluded that hawkers should not be viewed as a public nuisance. Instead, peddling food was a legitimate form of employment and a necessity for the working class population as hawkers provided cheap and affordable food.20 Nonetheless, the commission laid out a set of policy recommendations to resolve the issues arising from peddling food. It proposed the implementation of a licensing scheme so that the authorities would be able to monitor hawker activities and set conditions and regulations that would enable them to stipulate where hawkers could operate, as well as monitor their hygiene levels.21 Proper signage became mandatory and cooked-food hawkers were subjected to medical examinations and inoculation against infectious diseases.

To facilitate the licensing scheme, the commission recommended the appointment of a group of personnel to handle the issuing of licences and a force of Hawker Inspectors (at a ratio of about one to every 2,000 to 3,000 hawkers) to ensure that hawkers adhered to conditions stipulated in their licence agreements.22 Furthermore, the commission suggested that Hawker Inspectors receive a reasonable starting salary of $250 a month with allowance so that they would not be derailed by bribes. A Hawker Courts was advocated along with the establishment of a Hawker Advisory Board to advise on related matters such as the formulation of new policies and licensing procedure as well as to investigate and report on any grievances from hawkers.23 More importantly, the commission was of the view that hawkers should congregate and operate in hawkers’ shelters rather than on the streets. This implied that the government should in the long term consider building more hawker shelters that were equipped with basic facilities such as refuse bins, hot water, clean water and gas pipes.24

Despite the policy framework, the colonial administration was still unable to resolve the hawker problem. The number of illegal hawkers continued to rise, reaching over 30,000 by 1959.25 Moreover, hawkers continued to maintain their unhygienic food practices and operate in filthy environments. The unsanitary condition of the hawker scenes on Boon Tat Street, Upper Chin Chew Street and Beach Road was reported in The Singapore Free Press in 1957:

“A satay hawker had a pot of gravy, into which practically every customer dipped two or three times with the same stick. The sticks had been in their mouths a number of times. A hawker selling a Cantonese meal of roast pork, duck, entrails and rice was squatting near a stinking drain, while cutting the food stuffs. Flies flew about him… In some shops, food was stale and others sold pieces of meat left over by customers. A mee seller wiped perspiration from his body with his hands and then handled food. Some hawkers were seen buying rotten vegetables from street urchins who had salvaged the foodstuffs from dustbins. Many hawkers spat and rubbed their hands on their mouths and then served customers.”26

The failure to resolve the hawker problem was due to numerous factors. First, the government was slow to introduce the licensing scheme. In fact, the scheme was established three years after the commission’s report, and a proper Markets and Hawkers Department to manage it was not established until 1957.27 Second, there were not enough inspectors to monitor the hawkers. In 1958, there were only 16 inspectors monitoring the 30,000 hawkers operating in Singapore.28 Third, and perhaps the biggest factor, was that the authorities were unable to secure cooperation from the hawkers. This was mostly due to the all-out “war” the government had declared on unlicensed hawkers.29 Aided by the police, the Town Cleansing Department conducted daily raids. This caused many hawkers to resent the authorities, resulting in their defiance against the licensing policy. Many hawkers also resorted to bribing the enforcers or turning to the protection of secret societies and gangs.

Besides the hawkers, the daily raids irked both the Hawkers’ Union and the public. Rallying behind the hawkers, the Hawkers’ Union suggested that a better approach was not to punish the hawkers, but to work with them to preserve their livelihood by building shelters so that they would have an alternative site to continue their trade.30 In the 1950s, some hawkers formed syndicates to buy land and build markets and hawkers’ shelters. Some of these were located on Somerset Road, Sennett Estate, Mackenzie Road and Serangoon Road.31 However, this bold endeavour failed to trigger a similar response from the authorities. As a result, illegal hawker stalls and mass raids continued. It was only after Singapore became an independent nation in 1965 that a concerted government effort to resolve the hawker problem was made.

Building Hawker Centres

Leading the government effort to solve the hawker problem in the post-independence years was then Minister for Health Yong Nyuk Lin. He noted that the illegal hawker situation in Singapore had “gone on far too long and should be stopped”.32

Addressing Parliament in 1965, Yong acknowledged that while hawking was a legitimate livelihood, all hawkers should follow the rules and not threaten public health, traffic and law and order. He suggested that hawkers relocate to permanent premises. The first step was to register all the estimated 40,000 to 50,000 hawkers in Singapore so that the authorities could impose some control over them.33 In March 1966, the Ministry of Health (MOH) introduced the Hawkers’ Code. Under the code, a licence could only be issued to Singaporeans; in addition, hawkers were prohibited from plying their trade along streets with high traffic volume, in car parks during the daytime, around bus stops, and near schools and other public buildings.

The Hawkers Department under the MOH carried out the registration exercise over a period of time. When it concluded in 1969, there were about 24,000 registered hawkers, much lower than the previously estimated figure.

The Hawkers Department then began relocating the licensed street hawkers to temporary areas that were less busy.34 Those who plied their trades along the main roads were told to move to the back lanes, side roads, vacant lands or car parks. One of the most well-known car parks that served as a site for hawkers was the Orchard Road car park, which became known as Glutton’s Square. The relocation process required tact and sensitivity, with Members of Parliament and grassroots leaders stepping in to address the grievances of affected hawkers.

A special squad was also set up to deal with illegal hawkers. The squad would search and remove illegal hawkers from the streets by carrying out raids with auxiliary police officers. Offenders were fined before being referred to the Ministry of Labour for job replacement. Backed by a new confidence gained from economic progress and the creation of jobs, the Hawkers Department had by this time stopped issuing new hawker’s licences to able-bodied citizens, particularly those under 40. This was to encourage them to take on other jobs.35

The Hawker Centres Development Committee was set up in 1971 to plan for the development of hawker centres.36 Locations that were accessible to the public and provided potential business for the hawkers were selected. Rental at the hawker centres was also kept at nominal rates so that the hawkers did not have to raise their food prices after moving into these centres. The 110-stall Collyer Quay hawker centre, 80-stall Boat Quay hawker centre and the Yung Sheng Road hawker centre in Jurong were among the first hawker centres to be built.37

In 1972, the new Ministry of Environment took over the Hawkers Department as well as the responsibility of developing hawker centres. It also announced a programme to build 10 new hawker centres by 1975. These were located at Empress Place, Telok Ayer, North Bridge Road, Jalan Besar, Beach Road, Jurong Kechil, Ama Keng, Upper Thomson, Dunman Road and Zion Road. About 7,000 street hawkers were thus relocated to the new hawker centres.38 At the end of 1986, there were 113 hawker centres islandwide.39 In the same year, the government removed the last batch of 80 street hawkers congregating at China Square and Haw Par Villa.40 This brought to a close the government’s long struggle to relocate street hawkers into permanent premises.

Improving Hygiene Standards

The new purpose-built hawker centres were equipped with proper facilities for food preparation and cooking to improve hygiene standards. To complement this effort, the Environmental Public Health Act was introduced in January 1969. The legislation contained provisions to incorporate public health practices in the licensing and control of hawkers and food establishments.41 For instance, all stallholders were required to undergo medical examinations and immunisations. They had to seek permission to extend or make any alteration to their stalls. More importantly, they had to keep their stalls clean and ensure that their food was properly stored and safe for consumption. There was also an upward revision of penalties for offenders and stricter enforcement of public health regulations.

Despite these regulations, many hawkers still operated in filthy conditions. Many of them also continued unhygienic practices such as smoking, spitting and handling food without washing their hands.42 The Ministry of Environment undertook a series of public health education programmes in the 1970s and 1980s to promote good food hygiene. It also published a series of handbooks offering tips on food hygiene and food safety such as Clean Food for Better Health (1982) and Food for Thought (1989), and made it mandatory for food handlers to obtain a Food Hygiene Certificate before they could be registered.

In 1998, a grading system indicating the cleanliness of each stall replaced the demerit point system that had been implemented a decade earlier.43 An “A” grade implies excellence in cleanliness and food hygiene and “D” for below average standards. This is based on several criteria such as housekeeping standard, cleanliness level, food hygiene level and the hawker’s hygiene habits. Stallholders have to display their grades prominently so that the public are aware of the cleanliness levels of their stall. This move incentivised hawkers to maintain or improve their grades.

Hawker Fare as Heritage

With the hygiene problems resolved, the government began focusing on the heritage aspects of hawkers from the late 1980s onwards. In 1984, former Deputy Prime Minister S. Rajaratnam said that “a nation must have a memory, to give it a sense of cohesion, continuity and identity”.44 Since food has always been discussed in relation to ethnicity, diaspora and class identity, it was one of the ways to articulate the memories and multi-ethnic identity of the nation.45

Singapore’s vast variety of food – besides being harnessed for constructing and cementing a national identity – has been used by the Singapore Tourism Board (STB) to promote Singapore as a food paradise to boost tourism.46 The two biggest events organised by the STB are the Singapore Food Festival and the World Gourmet Summit. Held annually since 1994, the Singapore Food Festival is a month-long culinary event that celebrates Singapore’s food heritage and the local culinary scene, with the focus on the nation’s favourite hawker dishes. The World Gourmet Summit, started in 1997, is more upmarket and Western-centric, mainly showcasing the culinary creations of the best master chefs from around the world.

As more tourists began visiting hawker centres, the government embarked on the Hawker Centres Upgrading Programme in 2001.47 The programme, headed by the National Environment Agency, upgrades the conditions and facilities of hawker centres and markets that have deteriorated over time. Upgrading plans for hawker centres located in places with high heritage value were more elaborate. For example, the East Coast Lagoon Food Village was upgraded in 2001 with a tropical design complete with pavilions, gazebos, pitched roots, cabanas, tables and chairs on sand, and open-sided structures to allow itself to blend in with the seaside environment.48 At the time of writing, this beachfront hawker centre had been given another facelift and was due to reopen in December 2013. The Bedok Food Centre was designed based on the area’s history as a Malay kampong.49 It has an entrance roof inspired by the Minangkabau architecture style, outdoor landscaped restrooms and lush tropical vegetation. Other hawker centres that went through similar upgrades include Newton Food Centre and Tiong Bahru Market.

After the fight to ensure that hawkers could continue their trade, there are now concerns that Singapore’s hard-won culinary heritage could wane as there may not be enough Singaporeans joining the trade to replace the first- and second-generation hawkers.50 The younger generation thinks it is an unglamorous, menial and lowly job that is no longer a viable livelihood. Besides, most parents prefer their children to secure more cushy white-collar jobs instead. To retain and preserve traditional hawker food, the government has introduced initiatives such as lower stall rentals. It also resumed the construction of hawker centres, announcing that 10 new hawker centres would be built by 2016.51

New avenues are provided for aspiring hawkers. In 2013, Singapore’s Work Development Agency launched its first official hawker training programme.52 The programme introduces the basics of the hawker trade such as cooking basic hawker staples like roti prata and chicken rice, maintaining good food hygiene and innovative ways to display dishes in stalls. Furthermore, the government is considering setting up a training institute for hawkers. If this materialises, the school will hire successful hawkers to teach and transfer their skills to new hawkers.53 While these actions have generated a great amount of interest among Singaporeans, it remains to be seen whether they can help preserve the unique hawker culture of Singapore.

GENESIS OF THE MODERN FOOD COURT

Food Republic at Wisma Atria boasts 23 food stations and three mini-restaurants in a 23,000-square-foot space. Image courtesy of Food Republic.

Food Republic at Wisma Atria boasts 23 food stations and three mini-restaurants in a 23,000-square-foot space. Image courtesy of Food Republic.

As the construction of new hawker centres came to a halt, private food operators began setting up food courts. To differentiate themselves from hawker centres, food courts were air-conditioned. The first of its kind was the well-known Picnic Food Court, set up in 1985 in the basement of Scotts Shopping Centre along Scotts Road.54 Since then, such air-conditioned food courts have sprouted in many shopping centres, business parks, tertiary institutions and hospitals.

Other than air-conditioning, there are some marked differences between hawker centres and food courts. In hawker centres, stallholders are individual tenants whereas a single operator manages the food court and rents out the stalls. Invariably, the food prices in food courts are higher. Unfortunately, in many cases, food court fare tends to be slightly characterless thanks to the mass-produced standard recipes that these vendors use compared to rough and tumble hawker centres where one might find older hawkers who have been honing their craft for several decades using carefully guarded recipes. To be fair, however, such hawkers are a dying breed, and their children are not eager to take over the long hours and sweaty work that the job demands.

Cutlery and uniforms used in food courts also tend to be standard issue, and many food court operators employ a common design theme to brand their food court chains. Major food court operators in Singapore include Food Republic, Food Junction, Kopitiam and Koufu. Food Republic at Wisma Atria, for instance, has a 1960s theme complete with old furniture and stalls operating from pushcarts; another outlet at Suntec City Convention Centre was designed around the concept of a White Garden.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories — A Resource Guide; Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010).

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories — A Resource Guide; Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010).

REFERENCES

20,000 hawkers defy the law. (1949, October 3). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

7,000 unlicensed hawkers resited since 1968. (1975, August 12). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Bartley, W. (1932). Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate the Hawker Question in Singapore. Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. Retrieved from BookSG.

Cameron, J. (1865). Our tropical possessions in Malayan India. London: Smith, Elder and Co. [Reprinted 1965, Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.] Retrieved from BookSG.

Cheung, H. (2013, May 16) Can Singapore’s hawker food heritage survive? BBC News. Retrieved from BBC News website.

City opens hawker war. (1953, October 13). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Commission on hawkers appointed. (1950, April 18). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Feng, Z. (2013, January 9). 2 bodies to start training would-be hawkers. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hawkers draw up ‘charter’ to guard rights of 30,000. (1958, September 21). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Health Ministry committee to plan hawker centres. (1971, August 23). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Health officers alarmed at dangers. (1957, January 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hedwig, A., & Perera, A. (1985, October 6). Hawker centres or shocker centres? The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hot debate expected on expansion of Markets Department. (1958, May 29). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kanagasingam, F., & Ho, E. (1998, April 17). Hawkers worried about grading. The Straits Times, p. 44. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kong, L. (2007). Singapore hawker centres: People, places, food. Singapore: National Environment Agency. (Call no.: RSING 381.18095957 KON)

Kwek, M.L. (2004). Singapore: A skyline of pragmatism (p. 118). In R. Bishop., J. Philips., & W.W. Yeo (Eds.), Beyond description: Singapore space historicity. London: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216095957 BEY)

Lim, J. (2013, May 8). Singapore are the biggest spenders in Asia-Pacific for dining: Survey. (2013, May 8). The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website.

Minister suggests: Sell city as a food paradise. (1994, July 2). The Straits Times, p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mr Leow wants ‘big spaces’. (1953, December 19). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

New ministry’s $5m plan for hawker resettlement. (1972, September 25). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

‘No new licences for hawkers’ policy won’t be relaxed: Kim San. (1973, March 14). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Simpson, W.J. (1907). Report on the sanitary condition of Singapore. London: Waterlow & Sons. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission. (1950). Report of the hawkers inquiry commission. Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.798095957 SIN)

Singapore. Markets and Hawkers Department. (1957). Annual report of the Markets and Hawkers department. Singapore: The Council. (Call no.: RCLOS 338.31 SIN)

Singapore. Town Cleansing Department. (1948). Annual report 1948. Singapore: G.P.O. Available via PublicationSG.

Singapore Municipality. (1896). Administration report of the Singapore Municipality for the year 1895. Singapore: Fraser & Neave Limited. (Call no.: RRARE 352.05951 SIN; Microfilm no.: NL3351)

Siong, O. (2013, April 7). Hawkers cautious about sharing ‘trade secrets’ at proposed training institute. Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website.

Street hawking nuisance. (1905, October 12). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, W.J. (1971, August 27). 2 super hawker centres for the city. The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The last hawkers to be resited. (1986, April 29). The Straits Times, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wong, H.S. (2007). A taste of the past: Historically themed restaurants and social memory in Singapore (p. 124). In S.C.H. Cheung & C.B. Tan (Eds.), Food and foodways in Asia: Resource, tradition and cooking. London: Routledge. (Call no.: R 394.12095 FOO)

Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: Power relations and the urban built environment. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO)

NOTES

-

Lim, J. (2013, May 8). Singapore are the biggest spenders in Asia-Pacific for dining: Survey. (2013, May 8). The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Cameron, J. (1865). Our tropical possessions in Malayan India (pp. 65–66). London: Smith, Elder and Co. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Street hawking nuisance. (1905, October 12). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: Power relations and the urban built environment (p. 262). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO) ↩

-

Singapore Municipality. (1896). Administration report of the Singapore Municipality for the year 1895 (p. 62). Singapore: Fraser & Neave Limited. (Call no.: RRARE 352.05951 SIN; Microfilm no.: NL3351) ↩

-

Simpson, W.J. (1907). Report on the sanitary condition of Singapore (p. 16). London: Waterlow & Sons. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Bartley, W. (1932). Report of the committee appointed to investigate the hawker question in Singapore (pp. 3–4). Singapore: G.P.O. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Singapore Municipality. (1896). Administration report of the Singapore Municipality for the year 1895 (p. 62). Singapore: Fraser & Neave Limited. (Call no.: RRARE 352.05951 SIN; Microfilm no.: NL3351) ↩

-

Singapore Municipality. (1928). Administration report of the Singapore Municipality for the year 1927 (p. 23). Singapore: Singapore Municipality. (Call no.: RCLOS 363.61095957 SIN) ↩

-

20,000 hawkers defy the law. (1949, October 3). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Town Cleansing Department. (1948). Annual report 1948 (p. 24). Singapore: G.P.O. (Available via Publication SG) ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission. (1950). Report of the hawkers inquiry commission (pp. 11–12). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.798095957 SIN) ↩

-

Commission on hawkers appointed. (1950, April 18). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950, pp. 9–11, 16–17. ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950, pp. 16–17. ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950, p. 19. ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950, pp. 19–20. ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950, pp. 25–28. ↩

-

Hawkers draw up ‘charter’ to guard rights of 30,000. (1958, September 21). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Health officers alarmed at dangers. (1957, January 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Markets and Hawkers Department. (1957). Annual report of the Markets and Hawkers department (p. 1). Singapore: The Council. (Call no.: RCLOS 338.31 SIN) ↩

-

Hot debate expected on expansion of Markets Department. (1958, May 29). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

City opens hawker war. (1953, October 26). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mr Leow wants ‘big spaces’. (1953, December 19). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kong, L. (2007). Singapore hawker centres: People, places, food (pp. 27–28). Singapore: National Environment Agency. (Call no.: RSING 381.18095957 KON) ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1965, December 21). Addenda health (Vol. 24, col. 413). Singapore: Govt. Printer. (Call no.: RCLOS 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1965, December 30). Budget, Ministry of Health (Vol. 24, col. 802). Singapore: Govt. Printer. (Call no.: RCLOS 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

‘No new licences for hawkers’ policy won’t be relaxed: Kim San. (1973, March 14). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Health ministry committee to plan hawker centres. (1971, August 23). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, W.J. (1971, August 27). 2 super hawker centres for the city. The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New ministry’s $5m plan for hawker resettlement. (1972, September 25). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The last hawkers to be resited. (1986, April 29). The Straits Times, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1968, December 16). Second Reading of the Environmental Public Health Bill (Vol. 24, cols. 396–424). Singapore: Govt. Printer. (Call no.: RCLOS 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Hedwig, A., & Perera, A. (1985, October 6). Hawker centres or shocker centres? The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kanagasingam, F., & Ho, E. (1998, April 17). Hawkers worried about grading. The Straits Times, p. 44. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kwek, M.L. (2004). Singapore: A skyline of pragmatism (p. 118). In R. Bishop., J. Philips., & W.W. Yeo (Eds.), Beyond description: Singapore space historicity. London: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216095957 BEY) ↩

-

Wong, H.S. (2007). A taste of the past: Historically themed restaurants and social memory in Singapore (p. 124). In S.C.H. Cheung & C.B. Tan (Eds.), Food and foodways in Asia: Resource, tradition and cooking. London: Routledge. (Call no.: R 394.12095 FOO) ↩

-

Minister suggests: Sell city as a food paradise. (1994, July 2). The Straits Times, p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Environment Agency. (2019, March 21). Hawker Centres Upgrading Programme. Retrieved from National Environment Agency website. ↩

-

Cheung, H. (2013, May 16). Can Singapore’s hawker food heritage survive? BBC News. Retrieved from BBC News website. ↩

-

National Environment Agency. (2012, March 6). Sites for seven new Hawker Centres confirmed [Media News]. Retrieved from National Environment Agency website. ↩

-

Feng, Z. (2013, January 9). 2 bodies to start training would-be hawkers. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Siong, O. (2013, April 7). Hawkers cautious about sharing ‘trade secrets’ at proposed training institute. Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website. ↩