Time–forgotten Trades

Unable to keep pace with Singapore’s economic progress and development, many of Singapore’s early crafts and trades have disappeared. Sharon Teng tells us about these trades and what is being done to remember them.

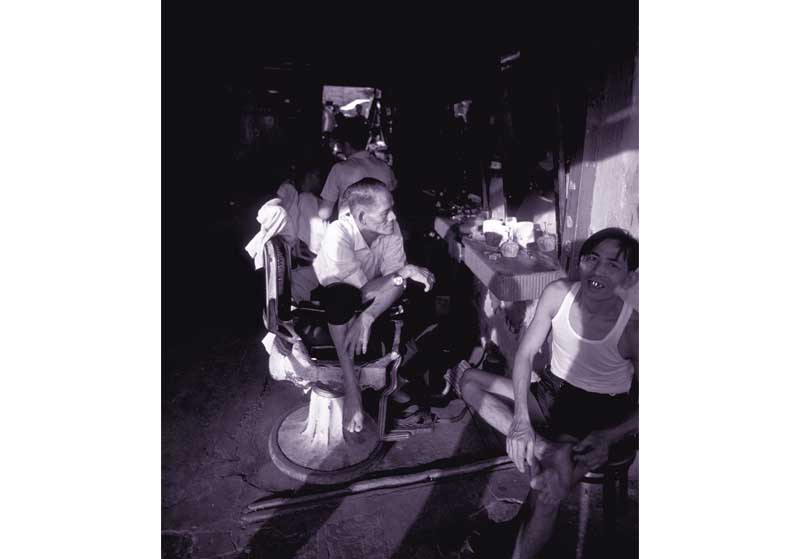

A barbershop along a five-foot way at Wayang Street in 1986. Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A barbershop along a five-foot way at Wayang Street in 1986. Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The streets of Chinatown, Little India and the arterial roads encircling the Central Business District were once crammed cheek by jowl with shophouses, street vendors and roadside stallholders peddling a mind-boggling variety of goods and services. These traditional peddlers are now virtually extinct — economic progress and urbanisation having dealt a death blow to these small-time trading activities.

From the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, there was a continuous influx of unskilled immigrants from China, India and Southeast Asia who came to seek their fortunes in Singapore. Many had minimal or no education, meagre possessions and limited funds. Some were already skilled tinsmiths, goldsmiths, locksmiths, seal carvers, image carvers, boat makers, and mask and dragon makers while others with more artistic inclinations had been trained as portrait and photo artists, opera actors and actresses, glove puppeteers and calligraphers. Others picked up various trades after they arrived in Singapore by serving as apprentices to local barbers, cobblers, furniture restorers and clog makers.

A few enterprising immigrants started plying their trades along the “five-foot-ways” — which was what sheltered pedestrian walkways measuring five feet wide were called in colonial times — in front of shophouses. These makeshift stalls sold inexpensive goods and services that required minimal financial outlay and equipment to set up. These trades were known as gho kha ki (Hokkien for “five-foot-way”) trades1 and included “knife sharpeners, streetside barbers, mask makers and fortune tellers” as well as “locksmiths, letter writers, traditional medicine men or bomoh” (Malay shaman) and several others.2

A Trade By Any Other Name

Merriam-Webster defines a tradesman or tradesperson as a skilled worker engaged in a particular trade or craft. Trades are an integral component of the manufacturing industry; in traditionally run businesses, inter-generational workers usually engage in labour-intensive work, sometimes using simple machinery or hand tools to produce a commodity for sale. Sullivan defines these trades as “making-things business” or “cottage industries”, emphasising the “handwork aspect of such manufacturing”.3 These trades are usually family-run, “have less than twenty workers, including [the] working proprietor; may consist of only one or two people … [and the] workspace and living space are combined or are nearby”. 4

Disappearing Trades

Over time, some trades have been completely obliterated due to dramatic changes in lifestyles or a drop in demand, such as charcoal dealers and craftsmen making paper bags, hair buns, daching (beam scales), wooden barrels, stools and masks.

Due to technological advancements and mechanisation, factories were able to mass-produce goods cheaply and more efficiently, contributing to the end of artisanal craftsmen such as tinsmiths, silversmiths and goldsmiths. The arduous life of a goldsmith, for example, with its long hours, meagre wages and a long apprenticeship (up to five years) discouraged new entrants into the profession.

Singapore’s evolving economic, land and labour policies also spelt the demise of these trades. During the 1980s and 1990s, many shophouses were demolished and itinerant five-foot-way peddlers relocated to flatted factories. The subsequent increase in overheads, coupled with anti-pollution regulations and the difficulty in finding new workers — particularly among the younger generation who eschewed manual work — made it impossible for the smaller trades and cottage industries to sustain their businesses.5

A few trades have survived the march of time, such as the mobile ice-cream cart vendor, roadside cobbler, traditional bakeries and provision shops and the odd shoe last maker, but their numbers are slowly dwindling and it is a matter of time before they are completely wiped out from the cityscape. There are sporadic openings of new “old” shops that try and recapture some of these time-honoured trades, but these are usually hard-nosed businesses that use nostalgia to create a commercial buzz. Chye Seng Huat Hardware in Tyrwhitt Road for instance is a hip coffee bar operating in a restored 1950s shophouse that still bears its original name, while Dong Po Colonial Café in Kandahar Street tries to recapture a slice of yesteryear with its old-fashioned butter cakes and thick black coffee.

Singapore’s Early Entrepreneurs: Five-Foot-Way Trades

Cobblers

History

When Singaporeans switched from wearing clogs to modern footwear during the 1950s, cobblers filled in the demand for shoe repairs. Many cobblers started out as shoe shop apprentices before setting up their own businesses. The trade comprised predominantly Chinese males, although there were also several Malay and Indian cobblers.

Job Scope

Cobblers worked flexible hours with incomes varying from month-to-month and provided services such as shoe polishing, replacement of worn-out heels and soles, and stitching-up of torn slippers. Some branched out into more premium services by making and selling their own slippers (capal) and shoes. Replacing the sole or heel of a shoe would have cost around $1.50 in the late 1970s, with the cobbler earning around $300 a month on average.

Tools of the Trade

Cobblers used an array of tools; “different kinds of knives, hammers, nails, pincers, adhesive, shoe lasts, shoe polish, shoe brushes, thread and needles, scissors, leather, vinyl, rags and rubber pieces”.6

Then and Now

Cobblers used to operate along five-foot-ways and roads in city areas. They stationed themselves at fixed locations or moved around housing estates on bicycle-carts filled with the tools of their trade. Traditional cobblers can still be found in Chinatown and Raffles Place, although they are gradually being replaced by shoe repair chains such as Mister Mint and Shukey Services that are conveniently located in shopping malls.7

Cobbler operating from pavement (1980). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Cobbler operating from pavement (1980). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Fortune Tellers

History

Chinese fortune-telling as a trade began in the 1800s when there was a huge influx of Chinese immigrants to Singapore. Having little or no education, people who needed help with selecting a felicitous date for a wedding or the opening of a shop for example, would seek the advice of a fortune teller.

Parrot astrology was the domain of Indian fortune tellers who originated mainly from Tamil Nadu and Kerala in South India.

Job Scope

There were several popular methods that Chinese fortune tellers used, such as palmistry, face reading, bazi (using one’s birth date to predict one’s destiny or to gauge the compatibility of a match-made couple), kau cim (using a set of 78 sticks for short-term predictions) and tung chu (using the almanac to select auspicious dates for important events such as weddings and shifting house).

Indian fortune tellers relied on their specially trained green parakeets to foretell the future. The bird would pick a fortune card based on the customer’s name and birth date. The astrologer would then interpret the image on the card (which depicted deities of different faiths, accompanied by lucky messages) that would address the customer’s concerns, which ranged from chances at the lottery and matrimonial compatibility to the recovery of a sick loved one.

Tools of the Trade

Chinese fortune tellers operated from a simple consultation booth, furnished with a small table and a few stools for customers. On display would be religious iconography such as the statue of Buddha or other Chinese deities, lit incense or joss sticks, pictures of palms, cards, bamboo sticks and books among others.

An Indian fortune teller, dressed in a white dhoti and shirt, would have had an even more basic set-up: a small table or even just the pavement itself, where a deck of 27 fortune cards would be displayed along with some charts, a notebook and caged parakeets. To supplement their paltry daily incomes of $10 to $15, they would also participate in cultural shows and trade exhibitions, earning up to $100 to $200 per job.

Then and Now

In the past, fortune tellers were usually found along five-foot-ways and on temple grounds. Today, Chinese fortune tellers are still commonly seen around Chinatown, at Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple on Waterloo Street, and at older HDB estates such as Bedok, Toa Payoh and Ang Mo Kio.

Parrot astrologers were based at Serangoon Road but they also made house calls, especially during festive occasions. Today, there are fewer than five still in business in Little India, as many Indians have ceased to believe in this method of divination.8

Parrot fortune teller at Serangoon Road in 1980. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Parrot fortune teller at Serangoon Road in 1980. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Ice-ball Sellers

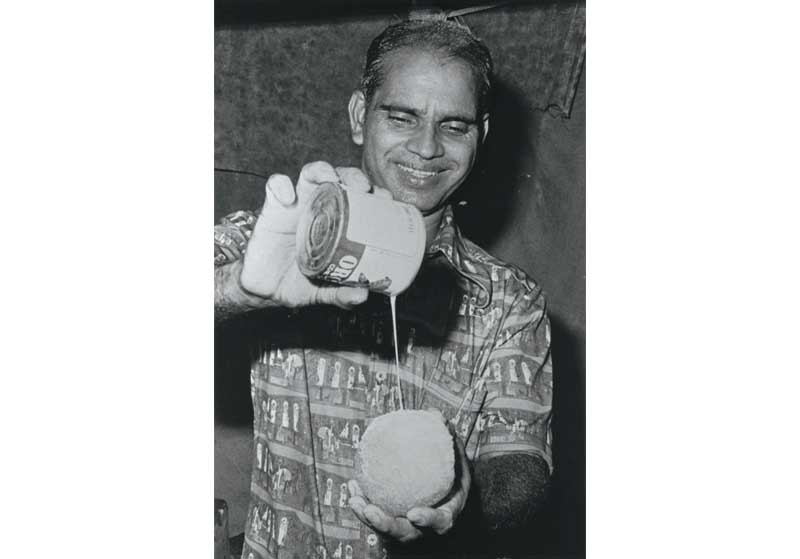

History

Ice-balls were hugely popular during the 1950s and 1960s, particularly among school children and teens. Iceball sellers were mostly Indian males, who sold drinks in addition to these cool delicious treats.

Job Scope

To make an ice-ball, the iceball seller would use a towel to press a block of ice against an ice shaver. One hand would hold a bowl beneath to catch the shavings. He would then shape the ice shavings into a semicircle, enclosing within ingredients such as cubes of agar-agar, or jelly, sweetened red beans and attap-chee (mangrove palm seeds). Using yet more ice shavings, he would deftly compact it into a spherical snowball. Then lashings of red and green and palm sugar syrup would be drizzled over the ice-ball, followed by a trickle of evaporated milk for added sweetness.

Tools of the Trade

The ice-ball vendor’s stall or pushcart would be packed with glass bottles of soft drinks and drinking glasses, plastic containers filled with various sugar syrup concoctions, ingredients for the ice-ball fillings and the all-important wooden ice shaver.

Then and Now

Ice-ball vendors were usually found near schools or along shophouses but sometimes moved to different locations with their mobile carts. Ice-balls are the predecessors of the more elaborate plated dessert called ice kachang sold in hawker centres and food courts. In 2011, ice-balls were brought back as part of the dessert menu at the Singapore Food Trail (a dining attraction featuring popular local dishes), located next to the Singapore Flyer.9

An Indian ice-water seller making a syrup coated ice-ball in 1978. Courtesy of Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA).

An Indian ice-water seller making a syrup coated ice-ball in 1978. Courtesy of Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA).Kachang Puteh Sellers

History

A Malay phrase, “kachang” (nuts, beans or peas) and “puteh” (meaning white) was a popular snack up until the 1990s. The peanuts coated with melted white sugar was one of the most popular varieties and probably accounts for the name “white nuts”. Kachang puteh originated from an Indian snack called chevdo.10 Nuts of various colours and prepared in a variety of ways (steamed, fried, roasted or coated with sugar) were sold by the vendors, who were mostly Indian.

Job Scope

The early itinerant kachang puteh seller hawked his wares stored in bottles or paper bags from a tray balanced on his head, moving from one location to the next. Some used pushcarts or bicycles, while others stationed themselves at fixed locales. Typically between five and 20 varieties of kachang puteh would be sold and each serving (either a single or mixed flavour of nuts) would be packed into rolled-up paper cones, using pages torn from old newspapers, Yellow Pages directories and school exercise books.

Tools of the Trade

Kachang puteh vendors either roasted and flavoured their own kachang at home (a lengthy and painstaking process) or bought ready-made kachang directly from suppliers.

Then and Now

Kachang puteh sellers used to frequent schools, cinemas, swimming pools and shopping centres. Such independent vendors have all but vanished today, except for perhaps the sole surviving kachang puteh seller in Singapore, Mr Nagappan Arumugam, who has manned a pushcart at Peace Centre on Selegie Road for over 20 years.11 Kachang puteh is now available in commercially pre-packed versions at supermarkets and 24-hour convenience stores all over Singapore. A pushcart stall can also be found at the Singapore Food Trail.12

A roadside kachang puteh seller (1985). Chu Sui Mang collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A roadside kachang puteh seller (1985). Chu Sui Mang collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Letter Writers

History

The thousands of illiterate and semi-literate Chinese immigrants in Singapore — coolies (manual workers), amahs (domestic helpers) and samsui women (female construction labourers from Guangdong Province) — who yearned to communicate with their families in China resulted in the demand for letter writers. The 1950s and 1960s were boom times for such letter writers, with long queues of people patiently waiting to send word back home after World War II, along with food, clothing and money. Letter writers were usually Chinese males in their 50s and 60s.

Job Scope

A letter writer would pen the feelings and thoughts of his customers and also read letters aloud for the illiterate, bridging the physical and emotional distance between relatives who resided thousands of miles away and their families in Singapore. The letters were written in a mixture of classical and vernacular Chinese. The writer would sometimes write “spring couplets, invitation cards, leases [and] marriage certificates”13 and, sadly, even suicide notes. Letter writers also wrote ancestral tablets for religious worship and to display at home for immigrants who moved into new residences. Due to the usually penurious circumstances of his clientele, the letter writer in the 1960s charged nominal sums for his services, such as a dollar per letter and earned about $250 a month.

Tools of the Trade

The letter writer’s stall was spartan, furnished with only a small table, one or two chairs and his writing instruments, comprising paper, Chinese brushes, ink and an abacus.

Then and Now

Letter writers were once a common sight in Chinatown but the trade lost its popularity after the 1980s with the passing of many old-time patrons. The increase in literacy and communication technology such as the telephone also contributed to the trade’s decline. Letter writers today focus primarily on writing ancestral tablets for the younger Chinese generation and entertain occasional requests from tourists to compose spring couplets and auspicious words or to have Chinese translations of their English names written.14

A letter writer with a customer along a five-foot-way in Kreta Ayer. From the Kouo Shang-Wei collection 郭尚慰收集. All rights reserved, family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board, Singapore, 2007.

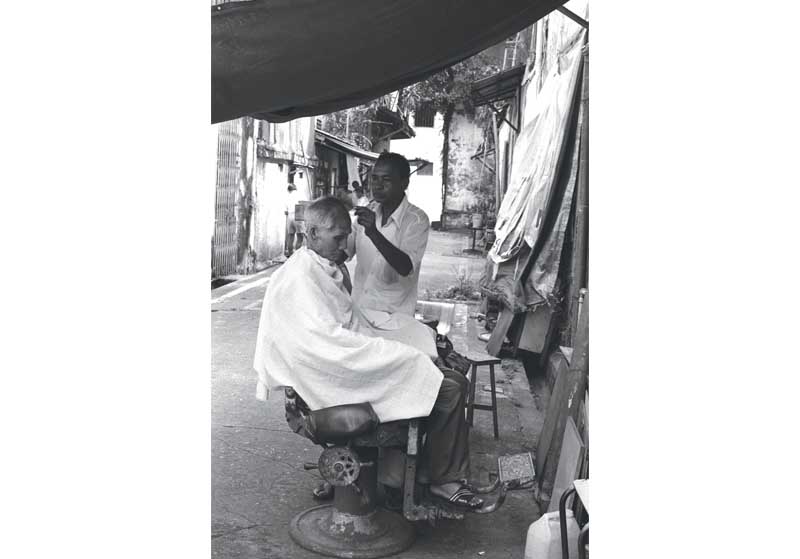

A letter writer with a customer along a five-foot-way in Kreta Ayer. From the Kouo Shang-Wei collection 郭尚慰收集. All rights reserved, family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board, Singapore, 2007.Street Barbers

History

Street barbers gained popularity after the 1911 Chinese Revolution, when Chinese immigrants who arrived in Singapore lopped off their braided “pigtails” (which had been a symbol of repression during the Qing Dynasty). Many barbers were self-taught, while some apprenticed at barbershops. The profession was equally represented by the Chinese, Malay and Indian races.

Job Scope

Operating along five-foot-ways or in roadside makeshift tents, street barbers offered haircuts, shaving, ear wax removal, nose-hair trimming, and scalp, face and shoulder massages.

Barbers worked from around eight in the morning to dusk, charging about 50 cents for a haircut in the 1960s, and raising their prices during the Chinese New year season to cater to increased demand. Some made house calls to shave the heads of babies or to provide haircuts for the elderly and infirmed.

Tools of the Trade

A street barber’s equipment usually included one to three barber chairs, several pairs of scissors, manual clippers, combs, brushes, razor blades, powder puffs and a mirror.

Then and Now

Street barbers once operated along the aptly named Barber Street, between Jalan Sultan and Aliwal Street and at the cobbled lane between Jalan Sultan and North Bridge Road. They were also found in Chinatown, Serangoon Road and Tanjong Pagar.

With the erection of high-rise flats in the 1960s, barbers plied their trade along the corridors of housing estates. Today, however, they operate out of air-conditioned shops found in virtually every neighbourhood, with modern equipment such as electric clippers and shavers. What has survived is the unique icon denoting these neighbourhood barbers — the barber’s pole, with its spinning helix of tri-coloured red, white and blue stripes.15

Barber at Tras Street in 1988. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Barber at Tras Street in 1988. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Immortalising the Trades of Yesteryear

Although many of the early trades and cottage industries no longer exist today, they have nonetheless left indelible imprints on the economic and social fabric of Singapore. Official documentation and archival records of these early trades act as historical and sociological testaments of how people lived and worked in early Singapore. These records acknowledge and pay tribute to the contributions of Singapore’s early entrepreneurs in the economic development of the island. At the national level, memory recorders and archivists hope that by helping the public understand the people and events that shaped the nation’s past, a deeper collective understanding and appreciation for Singapore’s history can be nurtured.

Cultural institutions, societies, commercial entities and private individuals have in their own ways expanded the government’s efforts — using traditional and new media, such as print, oral recordings, photographs, videos and social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter — to immortalise Singapore’s early trades and craftsmen. Exhibitions organised by societies and cultural groups with demonstrations of long-lost or soon-to-be-extinct trades deliver an experiential learning dimension for a contemporary audience by making history come alive through authentic recreations of the past.

Print and Digital Documentation

From a national perspective, libraries, museums and archives are seen as the appointed custodians and curators of the country’s social, economic, political and cultural history. In this vein, the Singapore Memory Project was started in 2011 as a national initiative “to collect, preserve and provide access to Singapore’s knowledge materials, so as to tell the Singapore Story”.16 Visitors to the portal, and its accompanying iremembersg blog, are able to view personal memories posted by members of the public on vanishing trades such as the “Chinese wayang”, “iceball vendor” and “painted typography”.

Other sources include articles on long-lost trades by the National Heritage Board, as well as newspaper articles from the National Library Board’s digitised newspaper archive, NewspaperSG. These articles provide credible first-hand accounts of significant historic personalities and events, and offer an objective binocular view of Singapore’s past.

Blogs17 created by individuals and community groups are private archival repositories shared with an online public audience. These blog entries express the blogger’s personal thoughts, opinions and insights. These “man-in-the-street” perspectives reveal the private expressions of what the national “Singapore Story” represents to distinct individuals in society.

Photographs

Photographs are visual records that present a still-life simulacrum of a bygone era. NLB’s PictureSG and the National Archives of Singapore’s (NAS) picture archives database, PICAS, provide a visual tableau of Singapore’s history and social development and serve as invaluable repositories of Singapore’s early trades and craftsmen.

Beyond that, image hosting social platforms such as Flickr allow users to share personal photographs. This enables disparate individuals and groups to engage and network, and facilitates the collective pooling of materials that result in a deeper and richer multi-varied historical narrative. Through the social platform medium, the subject of vanishing trades is reinvigorated for the digital generation.

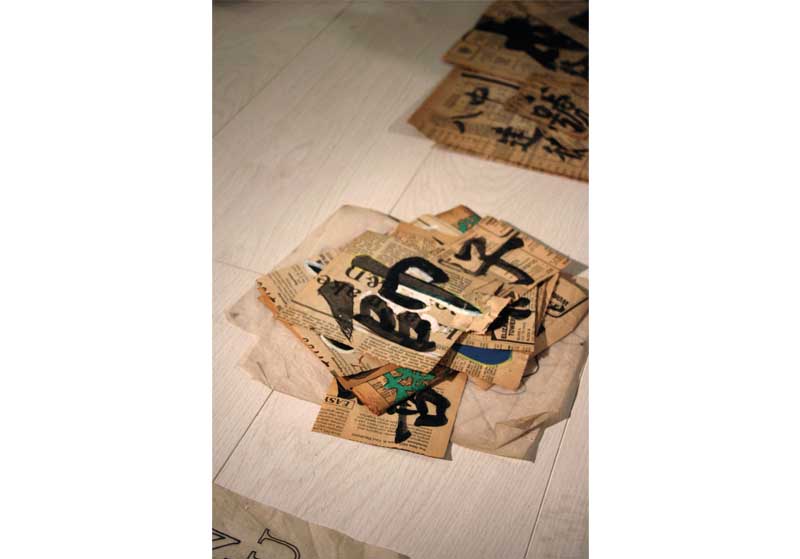

Exhibitions/Trade Fairs

“The Lost Arts of the Republic of Singapore”18 is an example of a vanishing trades project that straddles the physical and digital realms. This project was initiated by two local artists to “document the current state of vanishing arts and crafts of Singapore”. Through interviews with 10 existing practitioners, the artists crafted an exhibition for the Pop-Up Singapore House and London Design Festival in 2012, which presented a fresh interpretation of traditional symbols and transformed them into modern narratives. The exhibition was featured in two local journals (The Design Journal, March 2012, and Zaobao Fukan, July 2012). In addition, the artists posted photos of their exhibition and journal write-ups on Flickr.

"The Lost Arts of The Republic of Singapore" (2012) documented the vanishing arts and crafts of Singapore. Courtesy of Su-Jin Ng.

"The Lost Arts of The Republic of Singapore" (2012) documented the vanishing arts and crafts of Singapore. Courtesy of Su-Jin Ng.Through the decades, commercial and non-profit cultural organisations and societies such as the Singapore Handicraft Centre, Singapore Heritage Society, Chinatown Heritage Centre, Indian Heritage Centre and the Malay Heritage Centre have been actively organising cultural exhibitions and trade fairs, providing those still engaged in Singapore’s pioneering trades the opportunity to showcase dying or long-forgotten crafts or arts.19

In December 2011, the National Heritage Board put together a roving exhibition called “Traditional Provision Shops: A Thriving Past & An Uncertain Future”, which showcased 18 traditional provision shops and collectibles.20

The National Museum of Singapore has also curated several exhibitions on vanishing trades over the years, with the most recent being “Trading Stories: Conversations with Six Tradesmen” in March 2013, which featured true-life accounts of six pioneer tradesmen who have either retired or are still active in their occupations. 21

Some of the individuals featured in the 2013 exhibition, “Trading Stories: Conversations with Six Pioneering Tradesmen” by the National Museum of Singapore include samsui women and a movie poster painter. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Some of the individuals featured in the 2013 exhibition, “Trading Stories: Conversations with Six Pioneering Tradesmen” by the National Museum of Singapore include samsui women and a movie poster painter. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Oral Recordings

Established in 1979, the Oral History Centre of the National Archives of Singapore documents and provides access to the stories of individuals who have lived through significant moments in Singapore’s history. These oral records document Singapore’s political and social histories, covering periods such as the Japanese Occupation, political and leadership transitions and the development of the arts, education and sports, among other areas. The reflections and emotions of men and women who laboured and contributed towards Singapore’s economy in the pre- and post-war periods are captured in these interviews.

The recordings reveal fascinating details such as the reasons for entering or abandoning a trade, remuneration, details of goods and services provided, customer profiles, business practices, challenges and triumphs of the profession, anecdotes on training and apprenticeship, family stories and comparisons of past and present standards of living.

Documentaries and Dramas

Vanishing trades have been documented in local Chinese documentaries such as Vow of Celibacy (1980)22, The Vanishing Trades (1983)23 and My Grand Partner (webisode 11),24 which featured a traditional shoemaker and fountain pen repairman. These trades have also been the focus of local Chinese drama serials such as Five-Foot-Way (1987)25 and Samsui Women (1986).

Videos on vanishing trades can also be found on YouTube, posted by teachers and students for school projects, as well as film enthusiasts (through local short film competitions such as ciNE6526) and local history buffs and hobbyists.

Commemorative Memorabila

Vanishing trades have been featured in commemorative memorabilia such as the 1978 Straits Times calendars27 and a set of collectible econ minimart phonecards sold in 1996.28 Street traders of the early 1900s were also featured on a series of thematic MRT cards released in 1997.29

Samsui women, with their iconic red headgear and black trousers, have also been immortalised as dolls and t-shirt emblems sold at the Chinatown Heritage Centre. Photographs of samsui women were also displayed at bus stops during the M1 Singapore Fringe Art Festival in 2011.30

While the demise of these trades is inevitable due to economic progress and advancements in technology, continual efforts are being made at the individual, community and national levels to capture, document and preserve the memory of our early trades and the people who toiled at their crafts. We can take comfort that Singapore’s pioneer tradesmen and craftsmen will not likely disappear from society’s consciousness but continue to live on in our communal memories and national chronicles.

Sharon Teng is a Librarian with the National Library Board. She has contributed articles to BiblioAsia as well as Infopedia, NLB's online encyclopedia of Singapore. Her interest areas include the use of technology and social media in libraries.

REFERENCES

All kinds of everything along walkways of old. (1987, March 16). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chua, R. (1985, March 21). Vanishing trades? Can survive, la, says author. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Craftsman behind another vanishing trade…. (1977, November 19). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaprSG.

Economic Development Board. (1982). Report on the census of industrial production 1981. Singapore: Dept. of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 338.095957 SIN)

Economic Development Board. (2011). The report on the census of manufacturing activities 2011. Retrieved from Economic Development website.

Gee, J. (2008, January 15). The samsui women of today. The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ghetto Singapore. (2013). Vanishing trades of Singapore. Retrieved from ghettosingapore website.

Ho, S.B. (1996, February 8). Old trades a new hit in phone-card series. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Koh, S.T. (1987, March 16). Sweet-and-sour lives of pedlars of old. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Leong, W.K. (1997, May 13). He writes love letters, angry letters. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lim, J. (2013, March 15). Trading stories with six tradesmen. Retrieved from The Long and Winding Road website.

Lim, P., & Lim, S.T. (1982, June 6). Glimpses into trades and tidbits of bygone days. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lin, Z. (2005, May 21). Sell kachang puteh it’s a tough nut to crack. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Lo-Ang, S.G., & Chua, C.H. (Eds.). (1992). Vanishing trades of Singapore. Singapore: Oral History Department. (Call no.: RSING 338.642095957 VAN)

Lo-ang, S.G. (1992). Vanishing trades: A catalogue of oral history interview. Singapore: Documentatio Unit, Oral History Department. (Call no.: RSING 016.338643095957 SIN)

Mediacorp. (2013). My grand partner – Webisode 11 – shoe makers and pen repairing. Retrieved from xin,msn.com website.

Ministry of Defence. (2013). Vanishing trades in Singapore. Retrieved from Ministry of Defence website.

Nathan, D. (1990, March 12). Indian heritage to go on show at Indian village in two weeks. The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

National Archives of Singapore. (2002). PICAS. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

National Archives of Singapore. (2003). Collection of oral history collection database. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

National Heritage Board. (2013). Heritage along footpaths: Community Heritage series IV. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website.

National Heritage Board. (2013). Exhibitions: Trading stories: Conversations with six pioneering tradesmen. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website.

Naidu, R.T. (2018, July). Traditional cobblers. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Naidu, R.T. (2016). Five-foot-way traders. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Naidu, R.T. (2016). Roadside barbers. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Naidu, R.T. (2017). Letter writers. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Naidu, R.T. (2017). Parrot astrologers. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

National Library Board. (2013). Singapore memory portal. Retrieved from Singapore memory.sg website.

Ng, S., & Yeo, J. (2012). Lost arts of The Republic of Singapore. Retrieved from flickr.com website.

Phonecards retrace the early trades. (1994, February 13). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sim, G. (2004, April 12). Chinatown nightlife to return. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sng, M. (2002, June 30). She chews, she bites, she scores. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sullivan, M. (1985). “Can survive, la”: Cottage industries in high-rise Singapore. Singapore: G. Brash. (Call no.: RSING 338.634095957 SUL)

Tan, B.H. (1983, June 27). That old barber shop is going. The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, J., & Leong, W.K. (1977, November 24). ‘Protect our vanishing trades’ call to govt. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Teo, J. (2013). Vanishing trades/Scenes in Singapore. Retrieved from Jenniferteophotography.com website.

The vanishing trade: Trishaws in Singapore. (2010, May 17). Retrieved from sgtrishaws.wordpress.com website.

Toh, K. (2011, September 11). Keeping alive a vanishing trade. The Straits Times, pp. 16–17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Vanishing Trades. (1999). Retrieved from ThinkQuest Library website.

Vanishing trades: How do they fare? (1983, March 5). Singapore Monitor, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Vanishing trades MRT cards. (1997, June 29). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

‘Vanishing trades’ theme for Straits Times calendar. (1977, September 28). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

All kinds of everything along walkways of old. (1987, March 16). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Naidu, R.T. (2016). Five-foot-way traders. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

Sullivan, M. (1985). “Can survive, la”: Cottage industries in high-rise Singapore (p. 14). Singapore: G. Brash. (Call no.: RSING 338.634095957 SUL) ↩

-

Naidu, R.T. (2018, July). Traditional cobblers. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2013). Heritage along footpaths: Community Heritage series IV (pp. 4–5). Retrieved from National Heritage Board website; Naidu, Jul 2018. ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 2013, pp. 8–10; Naidu, R.T. (2017). Parrot astrologers. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore; Lo-Ang, S.G., & Chua, C.H. (Eds.). (1992). Vanishing trades of Singapore (pp. 60–64). Singapore: Oral History Department. (Call no.: RSING 338.642095957 VAN) ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 2013, pp. 12–14. ↩

-

Lin, Z. (2005, May 21). Sell kachang puteh it’s a tough nut to crack. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 21 May 2005. ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 2013, pp. 16–18. ↩

-

Lo-Ang & Chua, 1992, p. 36. ↩

-

Lo-Ang & Chua, 1992, pp. 35–37. ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 2013, pp. 20–22. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2013). Singapore memory portal. Retrieved from Singapore memory.sg website. ↩

-

Ghetto Singapore. (2013). Vanishing trades of Singapore. Retrieved from ghettosingapore website; Lim, J. (2013, March 15). Trading stories with six tradesmen. Retrieved from The Long and Winding Road website; The vanishing trade: Trishaws in Singapore. (2010, May 17). Retrieved from sgtrishaws.wordpress.com website; Teo, J. (2013). Vanishing trades/scenes in Singapore. Retrieved from pinterest.com wesbite; Vanishing Trades. (1999). Retrieved from ThinkQuest Library website. ↩

-

Ng, S., & Yeo, J. (2012). Lost Arts of the Republic of Singapore. Retrieved from flickr.com website. ↩

-

Nathan, D. (1990, March 12). Indian heritage to go on show at Indian village in two weeks. The Straits Times, p. 19; Lim, P., & Lim, S.T. (1982, June 6). Glimpses into trades and tidbits of bygone days. The Straits Times, p. 7; Craftsman behind another vanishing trade…. (1977, November 19). The Straits Times, p. 7; Sim, G. (2004, April 12). Chinatown nightlife to return. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Toh, K. (2011, September 11). Keeping alive a vanishing trade. The Straits Times, pp. 16–17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2013). Exhibitions: Trading stories: Conversations with six pioneering tradesmen. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website. ↩

-

Sng, M. (2002, June 30). She chews, she bites, she scores. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Vanishing trades: How do they fare? (1983, March 5). Singapore Monitor, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mediacorp. (2013). My grand partner – Webisode 11 – shoe makers and pen repairing. Retrieved from xin,msn.com website. ↩

-

All kinds of everything along walkways of old. (1987, March 16). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Defence. (2013). Vanishing trades in Singapore. This three minute video features the Wah Keow Hair Salon, located in Joo Chiat. The family-owned salon opened in 1954 and has been in operation for 59 years. This entry won the Jury’s Choice (Open Category) Best Editing award in the 2013 ciNE65 Season II competition. ↩

-

Craftsman behind another vanishing trade…. (1977, November 19). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaprSG. ↩

-

Ho, S.B. (1996, February 8). Old trades a new hit in phone-card series. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Vanishing trades MRT cards. (1997, June 29). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Gee, J. (2008, January 15). The samsui women of today. The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩