The Jiapu Chronicles: What’s in a Name?

Records of family lineage were important in traditional Chinese society. Lee Meiyu charts the history of these documents, or jiapu, which track not only family roots but also the social norms and cultural values of China at the time.

In ancient Chinese society, jiapu (家谱) or Chinese genealogy records, were created for the express reason of documenting the ancestry of each family. Before the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), lineage determined a person’s social class in China, and jiapu were used as official documents by the imperial court to prove the identity of a member of the ruling class and justify his position. This objective, however, evolved during the Song Dynasty when jiapu became a social tool to unify families by kinship instead. This shift took the practice of recording jiapu beyond the realm of the courts to the non-ruling classes, leading to a peak in genealogy studies and documentation.1

As genealogical studies flourished and matured in China, guidelines on how, what and when jiapu could be written were formulated. These guidelines were flexible and evolved with the times. As jiapu was a lineage blueprint that served as a basis for families to function, its presentation and content reflected the characteristics and beliefs of society at a particular point in time. As society evolved, so did the function of jiapu, and consequently, its content.

Invented Traditions and Nationalism

Although the history of jiapu documentation in Singapore can be traced to China, over time, the form and content of local Chinese genealogical records have evolved. In general, jiapu published by Singapore’s clan associations still follow the structure of older jiapu, since the majority of them are revised editions or compilations of the originals. However, with the introduction of the English language and influences from other cultures, the style and form of new genealogies written by Chinese families in Singapore have changed drastically.

This new form of jiapu is written in English and commonly records only three to five generations due to the short history of the migrant family, and includes names of female members, which is a departure from the traditional norm. Their contents are simpler, often comprising generation charts, oral history documentations and photographs. In fact, it might be more appropriate to describe these as family history records as opposed to traditional jiapu. The changing content of the new jiapu reflects the environment in which Singapore Chinese found themselves. For example, it is uncommon for clan rules to be detailed in jiapu in the context of a society with a fully developed legal system, as the legal framework would supercede the clan rules. These texts reflect a change in the purpose of recording jiapu; today, the documentation is more for creating a sense of self-identity than a social tool to regulate the functions of a clan.

In this essay, the rich history tracing the development of different chapters in a traditional Chinese jiapu will be explored, illustrated with selected examples from the National Library’s jiapu collection.

Women folding kim chua (paper money) for religious or ancestral offering along Clarke Quay in 1978. Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Women folding kim chua (paper money) for religious or ancestral offering along Clarke Quay in 1978. Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Title of Genealogy (Pu Ming 谱名)

In traditional practice, the title of a jiapu was important as it indicated which clan the records belonged to. It was common for the title to be made up of a combination of the name of the settlement area, surname, name of the ancestral temple, district-names, name of first migrant ancestor, and even the number of revisions done to the jiapu.2

Ancestral altar tablets displayed in a clan ancestral hall (1978). Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Ancestral altar tablets displayed in a clan ancestral hall (1978). Ronni Pinsler collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Introduction (Pu Xu 谱序)

Provenance was a very important criteria in jiapu. The reason and goals for revision, identity of the reviser, the year and background of revision, and the revision process were all recorded in the introduction. An interesting practice was to include all previous introductions found in the older editions of the jiapu in the current edition, so as to keep the provenance intact.

Apart from updating the jiapu with the latest clan members’ information, the compiler also had to ensure and verify that all information recorded was true, accurate and authoritative. This included information that had been recorded in the previous edition. Hence, it was not uncommon for earlier compilers to record unverified information and leave remarks for future generations to verify the content when new sources of information surfaced. Due to the nature of the research, compilers tended to be scholars or clan members who had an in-depth knowledge of classical texts.3

An ancestral hall of the Hakka community at Lorong Makam (1986). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An ancestral hall of the Hakka community at Lorong Makam (1986). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Origins of Surname (Xing Shi Yuan Liu 姓氏源流)

Chinese surnames have a long history. Some studies postulate that surnames first appeared in the matrilineal society of Chinese civilisation from approximately 5,000 to 3,000 BCE. Surnames were used to differentiate descent through maternal lines. As society became patrilineal, new surnames appeared, beginning with the ruling class. These new surnames were often derived from official titles, names of ruling areas or living places.4

Due to the form in which surnames were derived, they became associated with the historical developments of clans and revealed information about migration and ancestral history. Studies on Chinese surnames appeared as early as the Han Dynasty5 (206 BCE–220 CE), which explained the historical origins of each surname. Since jiapu served to document lineage, tracing the origin of a clan’s surname became an important chapter in the evolution of the jiapu. This was especially so if the surname could be traced to an ancient king or noble line that glorified the clan and affirmed their social status.

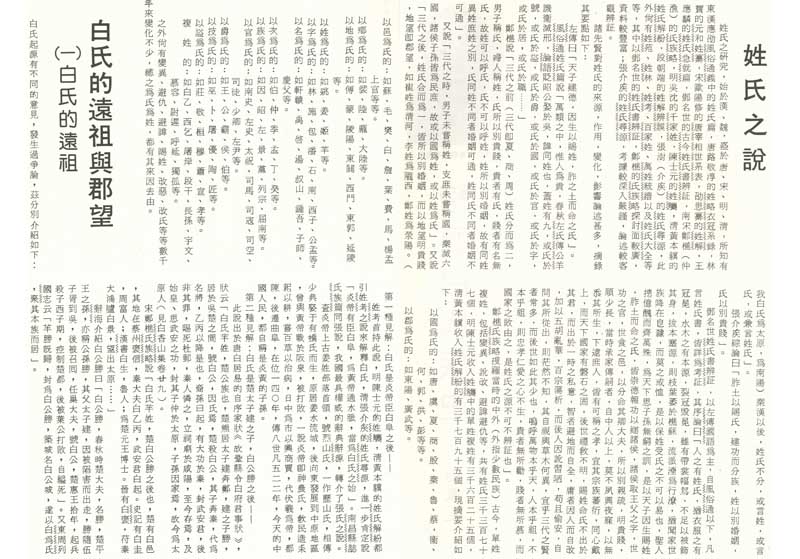

The chapter on surnames from the genealogy of the Bai (白) clan from Bangtou Town in Anxi County in Fujian province (福建安溪榜头), China, is a classic example of how surnames and district names reveal information about the lineage and migration history of a clan. The chapter begins by pointing out the uncertainty of the surname’s origin, with four possible origins proposed. These origins separately suggest that the Bai surname descended from either an official, Bai Fu (白阜), who lived during the pre-dynastic times of the Yan Emperor; Bai Fen (白份, 12th-century BCE), lord of the feudal state of Zhang; Bai Yibing (白乙丙, 7th-century BCE), a general of the State of Qin; or Bai Gongsheng (白公胜, 5th-century BCE), an advisor in the State of Chu.

The second section of this chapter deals with the origin of district-names (junwang 郡望) of the Bai clan. District names refer to the geographical areas where clans first originated or prospered. The district-names associated with the Bai clan are: Fengyi (冯翊, in modern-day Shanxi); Taiyuan (太原, in modern-day Shanxi); Nanyang (南阳, in modern-day Henan); and Xiangshan in the Luoyang area (洛阳香山, in modern-day Henan). This is followed by the migration history of the Bai clan from northern China into the southern regions. The first ancestor to migrate to Anxi was Yi Yu (逸宇公) during the Ming Dynasty in 1424 CE. Yi Yu escaped to Anxi with his family when they were falsely accused of treason.

A chapter in jiapu discussing the origins of the Bai surname. Here, the chapter explores the four possible origins of the Bai surname. All rights reserved. Genealogy of Peh Clan Pangtou Anxi Fujian China, 1989, Singapore Peh Clan Association, Singapore.

A chapter in jiapu discussing the origins of the Bai surname. Here, the chapter explores the four possible origins of the Bai surname. All rights reserved. Genealogy of Peh Clan Pangtou Anxi Fujian China, 1989, Singapore Peh Clan Association, Singapore.Generation Chart (Shi Xi Tu 世系图)

The Zhou Dynasty (1066–221 BCE) rulers incorporated the patriarchal lineage system into their ruling structure so successfully that it had a lasting impact on the entire Chinese civilisation. The Zhou people were ruled by a king who was known as the Son of Heaven. This position was passed down from a father to his eldest surviving son. Younger sons were conferred the title of feudal lords, and their titles were in turn inherited by their eldest sons. Lineages formed by the eldest sons of each feudal lord family were known as the “Main Branch” (dazong 大宗), while those formed by younger sons were known as the “Side Branch” (xiaozong 小宗). The Main Branch enjoyed higher social status than the Side Branch and was granted more privilege, respect and power. As blood relatives to the Son of Heaven, feudal lords were obliged to protect him and rule their given lands on his behalf. The Zhou ruling class created a society that used lineage as the basis to determine the distribution of wealth and power. This set of societal rules was known as the “System of Lineages” (zong fa zhi du 宗法制度).

The Zhou ruling system did not survive after the fall of the dynasty. However, it was later adopted by the Chinese as a means to organise their clans. The concepts of Main Branch and Side Branch were adopted into jiapu, which recorded every clan members’ ancestry and served as documented proof of his inheritance rights and social status. The documentation methodology matured with the publication of two ground-breaking works during the Song Dynasty — “The genealogy chart of the Ouyang clan” (Ouyang shi pu tu 《欧阳氏谱图》) and “The genealogy of the Su clan” (Su shi zu pu 《苏氏族谱》). The authors, Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修) and Su Xun (苏洵), became the pioneers of traditional Chinese genealogy.6

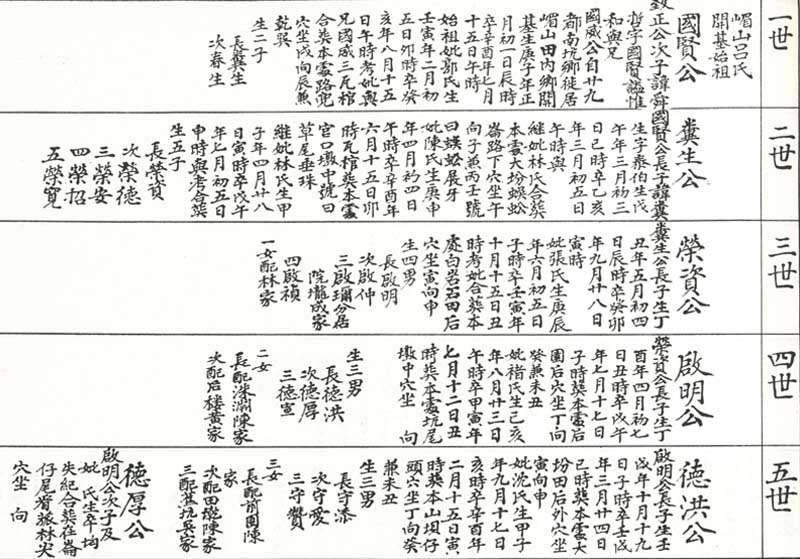

The generation chart of the Lu (吕) clan from Tiannei Town in the Meishan area (嵋山田内) is an example of how traditional Chinese generation charts are laid out. Read from right to left, the rightmost column of the chart states the different generations of the clan, with the first generation at the top and the fifth generation at the bottom. Descendents of the same generation are placed side by side, with the oldest to the youngest son in the same row. The genealogy is composed of several charts, and limiting the documentation to five generations per chart was a concept first proposed by Ouyang Xiu and Su Xun. Both defined the Side Branch as descendents of younger sons within five generations, with Su Xun also stating that generations beyond the fifth were no longer considered as part of the clan.7 In modern Chinese genealogy this restriction is not followed, even though the representation of five generations in a chart is generally still practised.

The concept of the Main Branch stipulated that eldest sons of eldest sons formed the main bloodline of a clan, and they could inherit the privileges and responsibilities of a clan patriarch. Such privileges included the inheritance of wealth, power and social status. The responsibilities of a clan patriarch was to ensure clan harmony, lead ancestral rites and prayers, and groom the next patriarch, thus ensuring the bloodline remained unbroken.8 The clan patriarch of each generation had great power and control over other clan members who were considered to be of lower hierarchy. In the Lu generation chart, the names of the eldest sons in each generation are written directly below their fathers’ names in larger text, at the beginning of the second column. The clear presentation of continuous lineage serves as an easy reference to determine the hierarchy of a member in relation to others in the clan.

The Lu clan’s generation chart is an example of how traditional Chinese generation charts are laid out. It is limited to five generations, with the first generation at the top and the fifth at the bottom. It is read from right to left. Meishan Tiannei Lu shi jiapu (Genealogy of the Loo clan from Tiannei Town in the Meishan area), 1994, Singapore Loo Clan Association, Singapore.

The Lu clan’s generation chart is an example of how traditional Chinese generation charts are laid out. It is limited to five generations, with the first generation at the top and the fifth at the bottom. It is read from right to left. Meishan Tiannei Lu shi jiapu (Genealogy of the Loo clan from Tiannei Town in the Meishan area), 1994, Singapore Loo Clan Association, Singapore.Generation Names (Zi Bei 字辈)

Generation names were used to differentiate the generation that clan members belonged to within a large clan, which would in turn determine the appropriate greeting and conduct of members. Those born in the same generation would have the same Chinese character as the first character of their names. In most cases, clans would use Chinese characters from a poem that recorded meritorious clan deeds or virtues valued by the clan as the sequence of characters to be used. Hence, clan members would be able to infer the seniority of another based on the sequence of their generation names as indicated in the poem.9

Ancestral Hall (Ci Tang 祠堂)

Ancestor worship is an important activity in Chinese culture, based on the belief that the spirits of the dead can influence the activities of the living. In order to gain the blessings of the spirits, rites are performed to appease them. Apart from obtaining blessings, ancestral rites also serve as important familial focal points and reminders of their blood ties. Ancestral tablets of a clan are housed in an ancestral hall and this is also where the jiapu is kept. The ancestral hall is a physical manifestation of the connection between the generations, bestowing a sense of identity on the clan as a whole as well as individually.

The naming of the ancestral hall is of utmost importance. An appropriate name reflects the history of the clan or reminds future generations of a desired virtue. It is common for ancestral halls to be named after the district names of the clan. In traditional Chinese society, one’s district name was often introduced together with one’s surname at social gatherings; this would enable others to know which ancestral temple and clan a person belonged to.10

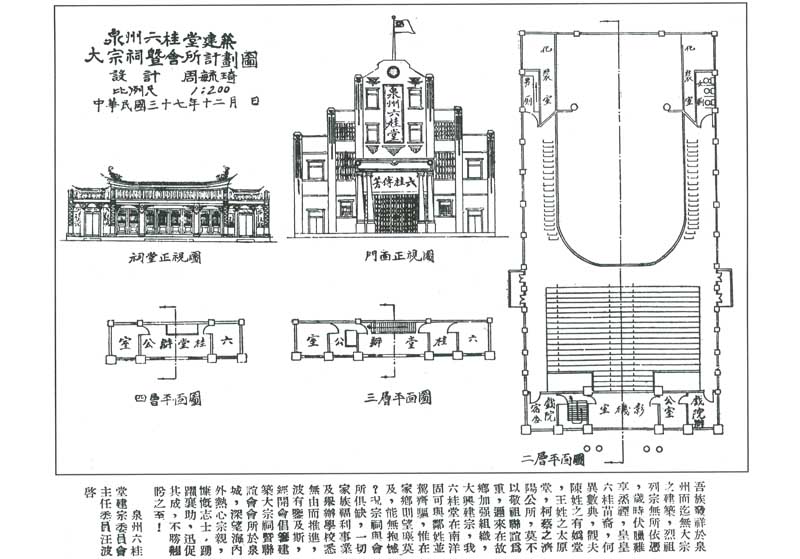

Some jiapu are named after their ancestral halls, such as the genealogy of the Liugui Hall (六桂堂). Although the term liugui is not the district name of the clan, there is good reason for naming it so. The original surname of the clan was Weng (翁), descendents of the royal family of the Zhou Dynasty. During the Song Dynasty, six brothers were successful in the imperial examinations and became officials. It was a glorious occasion for the clan and the event was remembered as liu gui lian fang (六桂联芳), meaning “the six brothers who became officials”. Hence, the term liugui was associated with this significant historical event, and was used to remind descendents of their ancestors’ achievements. The six brothers later adopted different surnames — Weng (翁), Hong (洪), Fang (方), Gong (龚), Jiang (江), and Wang (汪), and lived in different parts of China. Although the descendents of these six branches live separately and have different surnames, they maintain contact with each branch through their local ancestral halls that have preserved their clan records.

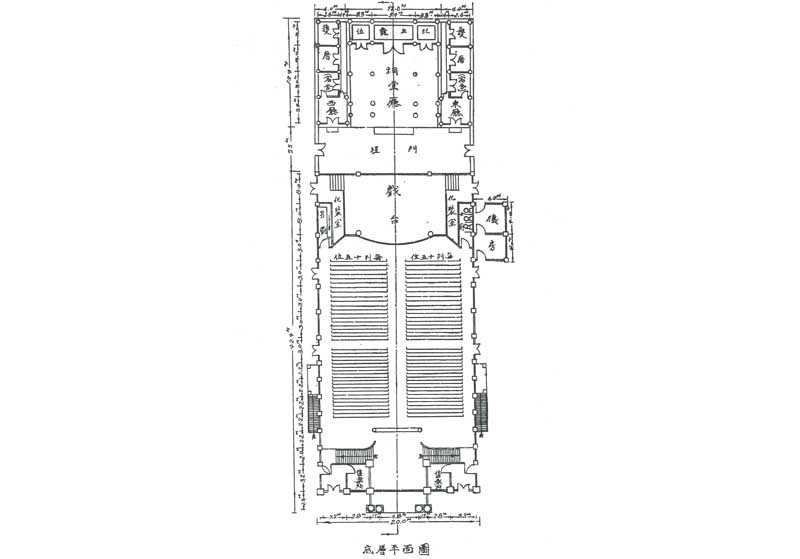

A 1949 drawing plan shows the Liugui Hall built in Quanzhou, China — where the six brothers originated from. There was a hall for ancestral tablets, management offices for clan members and a stage for Chinese opera. Their jiapu was republished in conjunction with the construction of the ancestral hall.

Floorplans of the ancestral hall of the Liugui clan. Ancestral halls were the focal points for clans, where ancestral tablets were kept, and ancestral worship rites and other clan activities took place. All rights reserved. Leok Kooi Tong genealogy, 1949, Hong Tiansong, Leok Kooi Tong, Quanzhou.

Floorplans of the ancestral hall of the Liugui clan. Ancestral halls were the focal points for clans, where ancestral tablets were kept, and ancestral worship rites and other clan activities took place. All rights reserved. Leok Kooi Tong genealogy, 1949, Hong Tiansong, Leok Kooi Tong, Quanzhou. Lands Belonging to the Ancestral Hall (Ji Tian 祭田)

Funds were needed to upkeep the ancestral hall as well as pay for the expansion of the building, the performance of ancestral rites, clan events, distribution of money to needy members, and even updating of the jiapu. Different households would contribute funds to the ancestral hall, but it was common for richer clan members to donate land to the ancestral hall. These were rented out as sources of revenue that went to the management of the ancestral hall. Information on these lands was often recorded in the jiapu as well.11

Biographies (Zhuan Ji 传记)

Biographical writings in jiapu appeared as early as the Han Dynasty. An example would be the “Records of the Grand Historian” (Shi ji《史记》) by Sima Qian in which a compilation of 12 royal genealogies appeared in the “Imperial Biographies”. Biographical writings continued to appear in jiapu, eventually forming its own chapter. As biographies detailed the lives of individuals, they were used to highlight illustrious ancestors, glorifying the clan indirectly.12

Similar to biographies were chapters of “Ancestor Portraits and Praises” (zu xian xiang zan 祖先像赞) and “Records of Meritorious Deeds” (en rong lu 恩荣录). Important individuals such as first migrant ancestors, ancestors within the nine generations, ancestors who had illustrious careers, and ancestors who had performed virtuous or meritorious acts are included in these chapters.

Biographies typically only contain text, while “Ancestor Portraits and Praises” include pictures and poems that praise the importance of an individual. The biographies in the genealogy of the Xu (许) clan from the Shigui and Yaolin areas in Jinjiang, Fujian (福建晋江石龟瑶林) combine both the “Ancestor Portraits and Praises” and biographical writings into one chapter. It highlights the first migrant ancestor of the Shigui and Yaolin branch, Ai (Ai Gong, 爱公). The poem recounts that Ai, on orders from the imperial court, was assigned to develop the Quanzhou area during the Tang Dynasty. The biography states the year of his assignment (678 CE) and that he moved from Yaolin to Shigui in 710 CE after deciding that Yaolin was too small for the clan if its numbers grew. Ai was a general with an illustrious military career and had three sons. The ancestral temple honouring him and his sons was destroyed and rebuilt several times over the course of time.

Clan Rules (Jia Fa 家法)

Besides documenting familial ties, jiapu were also instrumental in guiding members’ conduct towards one another to promote harmony and cohesion within the clan. This appeared in a chapter called “Clan rules”. Clan rules was a set of moral teachings stating how clan members should behave in order to avoid conflict.13

The genealogy of the Huang (黄) clan from Pengzhou and Xialu village (蓬洲霞露) had 15 rules to abide by: to be filial, maintain harmony within the clan, maintain peace with neighbours; be humble and courteous; committed to work; to strive for knowledge; obey teachers; maintain ancestors’ graves; avoid having same names as elders; avoid court cases; avoid bad habits; obey superiors; avoid deviating from sagely teachings; avoid committing crimes; and to revise jiapu regularly. This was followed by a chapter on implementing the rules in daily activities.

Such chapters were heavily influenced by Confucian teachings on respecting authority and elders, and emphasised that rituals were important activities that reinforced hierarchy and united clan members. These chapters also proved that jiapu were used as basic documents that recorded the “laws” of a clan.

Conclusion

The jiapu chapters discussed here offer only a peek into the wealth of information found in traditional Chinese genealogical records. There are no fixed rules on how to write a genealogy, and many Chinese families have adapted aspects of jiapu that best suit the needs of their families. As a result, jiapu is an ever-evolving document that captures the characteristics of society at a particular point in time, and also offers a glimpse into the historical continuity of Chinese family structure and beliefs.

In traditional Chinese society, jiapu could comprise the following 18 types of information14

- Ancestor portraits and praises

- Content page

- List of editorial members

- Introduction

- Writing style guide

- Records of meritorious deeds

- Genealogy studies and its history

- Origin of surname

- Generation chart

- Biographies

- Clan rules

- Clan practices

- Ancestral hall

- Ancestral graves

- Clan properties

- Documents pertaining to properties

- Literary works

- List of members who had a copy of the genealogy

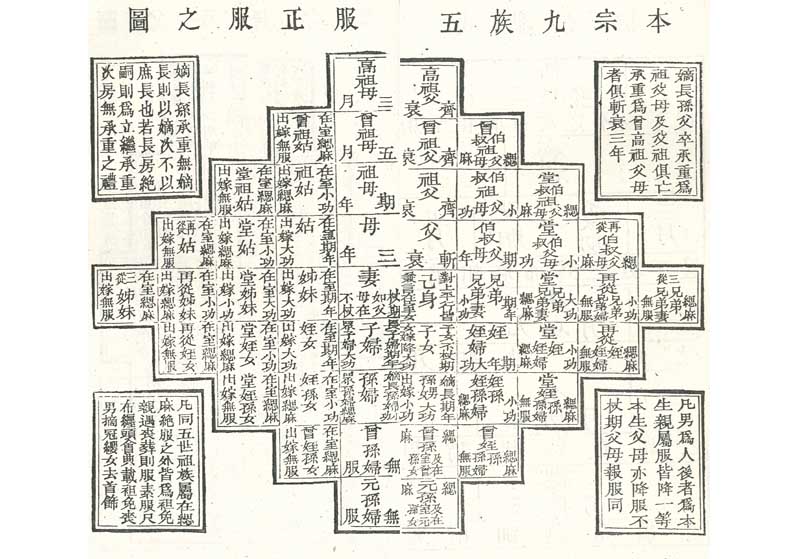

FIVE DEGREES OF MOURNING CLOTHES (WUFU 五服)

Wufu was the set of rules that determined the mourning clothes and mourning periods to be observed by different clan members within nine generations (jiu zu 九族). The nine generations were defined as the four generations before oneself (from father to great great-grandfather) and the four generations after oneself (from children to the great great-grandchildren). Mourning clothes were separated into five different types, and mourning periods ranged from three months to three years. In general, the closest kin to the deceased wore the coarsest fabric and observed the longest mourning period. These five degrees of mourning were separately known as zhancui (斩衰); zicui (齐衰); dagong (大功); xiaogong (小功); and sima (缌麻).15

A wufu chart was used to determine the mourning clothes and duration of mourning for a clan member. All rights reserved. Ningxiang Nantang Liu shi si xiu zupu (Genealogy of Liu clan from Nantang Town in Ningxiang County), 2002, Chen Zhanqi, China National Microfilming Center for Library Resources, Beijing.

A wufu chart was used to determine the mourning clothes and duration of mourning for a clan member. All rights reserved. Ningxiang Nantang Liu shi si xiu zupu (Genealogy of Liu clan from Nantang Town in Ningxiang County), 2002, Chen Zhanqi, China National Microfilming Center for Library Resources, Beijing.

MEMORIAL ARCHES (PAI FANG 牌坊)

In general, there were two main types of memorial arches: the Meritorious Deeds Memorial Arch (gong de pai fang 功德牌坊) and the Virtuous Memorial Arch (dao de pai fang 道德牌坊). These arches glorified the clan and reminded descendents of desired virtues and conduct through the stories inscribed on the arches. Memorial arches were sometimes located near the ancestral hall and considered part of the compound.

In traditional Chinese society, women were usually not mentioned in jiapu, unless they had given birth to sons, in which case, their surnames would be recorded. However, if a widow did not re-marry after the death of her husband, her virtue would earn her a chastity memorial arch. These women were also granted a chapter in the biographical section of the jiapu, which was considered to be a great honour.16

Lee Meiyu is a librarian at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at the National Library Board. The subject of genealogy is close to her heart and she has worked on resource publications that complement NLB’s exhibitions such as Money by Mail to China: Dreams and Struggles of Early Migrants (2012) and ROOTS: Tracing Family Histories — A Resource Guide (2013).

REFERENCES

Bose, J.K., & Palmer, S.J. (Eds.). (1972). Studies in Asian genealogy. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 929.1095 WOR)

程维荣 [Chen, W.]. (2008). 中国近代宗族制度 [The lineage organisations in Contemporary China]. Shanghai: Xuelin. (Call no.: Chinese R 306.830951 CWR)

陈湛绮 [Chen, Z.]. (2002). 宁乡南塘刘氏四修族谱 [Genealogy of Liu clan from Nantang Town in Ningxiang County]. Beijing: China National Microfilming Center for Library Resouces. (Call no.: Chinese R q929.20951 NXN)

Hong, T. (1949). Leok Kooi Tong genealogy. Quanzhou: Leok Kooi Tong. (Call no.: RCO 929.20951 LEO)

Jones, R. (1989). Chinese names: The use of Chinese surnames and personal names in Singapore and Malaysia. Petaling Jaya, Selangor: Pelanduk Publications. (Call no.: RSING 929.4 JON)

Kee, P., Chai, K.K., & Zhuang, G. (Eds.). (2002). Genealogies and Chinese migration studies. Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centre. (Call no.: RSING 929.1072051 GEN)

Lim, P. (1988). Myth and reality: Researching the Huang genealogies. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 929.108995105957 LIM)

刘黎明 [Liu, L.]. (2007). 血脉 : 祠堂•灵牌•家谱的传承血亲习俗 [The continuity of lineage practices in ancestral halls, ancestral tablets, and genealogies]. Taipei: Shuquan. (Call no.: Chinese R 306.830951 LLM)

Meishan Tiannei Lu shi jiapu [Genealogy of the Loo clan from Tiannei Town in the Meishan area]. (1994). Singapore: Singapore Loo Clan Association.

蓬洲霞露黄氏族谱 [Genealogy of the Huang clan from Pengzhou and xialu]. (n.d.). [China]: [publisher not identified]. (Call no.: Chinese RCO 929.20951 PZX)

钱杭 [Qian, H.]. (2001). 血缘与地缘之间 : 中国历史上的联宗与联宗组织 [Connection between blood and locality – the history of combined ancestry and their organisations]. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press. (Call no.: Chinese R 929.351 QH)

Singapore Peh Clan Association. (1989). Geneaology of Peh Clan Pangtou Anxi Fujian China. Singapore: Singapore Peh Clan Association. (Not available in NLB holdings)

王鹤鸣 [Wang, H.Z.] (2011). 中国家谱通论 [General discussion on genealogies in China]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Publishing House. (Call no.: Chinese R 929.1072051 WHM)

Xu, J. (1987). Fujian Jinjiang Shigui Yaolin Xu shi zupu [General discussion on genealogies in China]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Publishing House.

Xu, J. (2002). Zhongguo de jiapu [The genealogies of China]. Tianjin: Baihua Literature and Art Publishing House.

朱洪斌 [Zhu, H.Z.]. (2006). 寻根问祖 : 中华姓氏源流 [The origin and history of Chinese surnames] (pp. 11─13). Beijing: Unity Press. (Call no.: Chinese R 929.420951 ZHB)

NOTES

-

王鹤鸣 [Wang, H.Z.]. (2011). 中国家谱通论 [General discussion on genealogies in China] (pp. 50–115). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Publishing House. (Call no.: Chinese R 929.1072051 WHM) ↩

-

钱杭 [Qian, H.]. (2001). 血缘与地缘之间 : 中国历史上的联宗与联宗组织 [Connection between blood and locality – the history of combined ancestry and their organisations] (pp. 82–109). Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press. (Call no.: Chinese R 929.351 QH) ↩

-

朱洪斌 [Zhu, H.Z.]. (2006). 寻根问祖 : 中华姓氏源流 [The origin and history of Chinese surnames] (pp. 11─13). Beijing: Unity Press. (Call no.: Chinese R 929.420951 ZHB) ↩

-

程维荣 [Chen, W.]. (2008). 中国近代宗族制度 [The lineage organisations in Contemporary China] (pp. 31–39). Shanghai: Xuelin. (Call no.: Chinese R 306.830951 CWR) ↩

-

刘黎明 [Liu, L.]. (2007). 血脉 : 祠堂•灵牌•家谱的传承血亲习俗 [The continuity of lineage practices in ancestral halls, ancestral tablets, and genealogies] (pp. 1–32). Taipei: Shuquan. (Call no.: Chinese R 306.830951 LLM) ↩

-

陈湛绮 [Chen, Z.]. (2002). 宁乡南塘刘氏四修族谱 [Genealogy of Liu clan from Nantang Town in Ningxiang County] (pp. 535–542). Beijing: China National Microfilming Center for Library Resouces. (Call no.: Chinese R q929.20951 NXN) ↩