Kampung Living: A–Z

It’s hard to believe that Singapore was once a sleepy village outpost. Re-live those nostalgic kampung days with this laundry list of life as it once was.

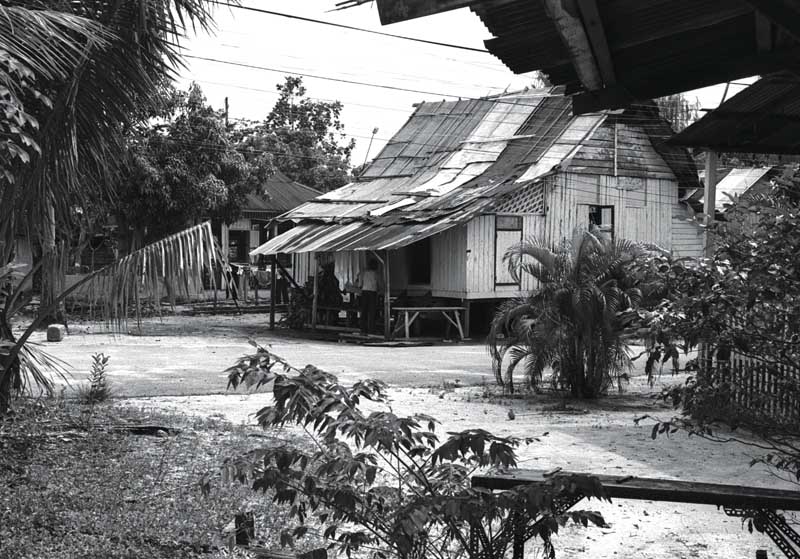

A Malay house in Kampong Bedok Luat. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Malay house in Kampong Bedok Luat. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Singapore is a city that rarely sleeps – commuters, workers, students and holiday-makers contribute to its near-insomniac thoroughfares, offices and shopping malls, blurring the transition from night to day. The breaking of dawn was more discernible until the early 1970s when many parts of Singapore were made up of kampungs (villages). Then, distinct sounds and habits signalled the end of nighttime and the start of a new day as W. Alexander wrote in The Straits Times in 1936:

Nowhere in the world does the first flush of dawn [signal] a more rapid and general awakening than in Singapore… The noisy splash of water indicates early ablutions in one direction, while from another the clatter of cooking utensils and plates gives promise of breakfast on the way. Charcoal fires, slumbering throughout the night, leap to life when fanned… while a noisy clatter as pails are banged on stone draws attention to the first patron of the standpipe — an elderly woman who carries her burdens slung from a yoke… Perhaps a quarter of an hour, perhaps twenty minutes after the first streak in the sky, Singapore has fully awakened from its slumber.1

Many older Singaporeans would argue that their kampung days had a lot more character, their memories of village life firmly etched in their collective consciousness even as the physical landscape, structures and habits of the kampung disappeared over time. The act of recollecting the past, however, can be a delightfully haphazard exercise. To sharpen your musings, BiblioAsia presents an A-Z laundry list of kampung living as it once was.

Arang and Anglo: Poor Man’s Kitchen

Starting grandmother’s old kitchen fire2 was a huff-and-puff affair.3 Pre-war households mostly relied on firewood, except for a few city dwellers who used arang (charcoal), gas or electricity.4 Many kampung folks manually stoked the fire from their firewood or arang stoves, fanning the coals furiously to keep them burning. Firewood and arang were sold by weight (or pikul) and delivered via pedal tricycle or a two-wheel wooden cart. Although more expensive, many women preferred arang as it could be broken into small pieces by hand unlike firewood which had to be chopped with a hatchet.5 Accompanying the arang was the clay stove or anglo.

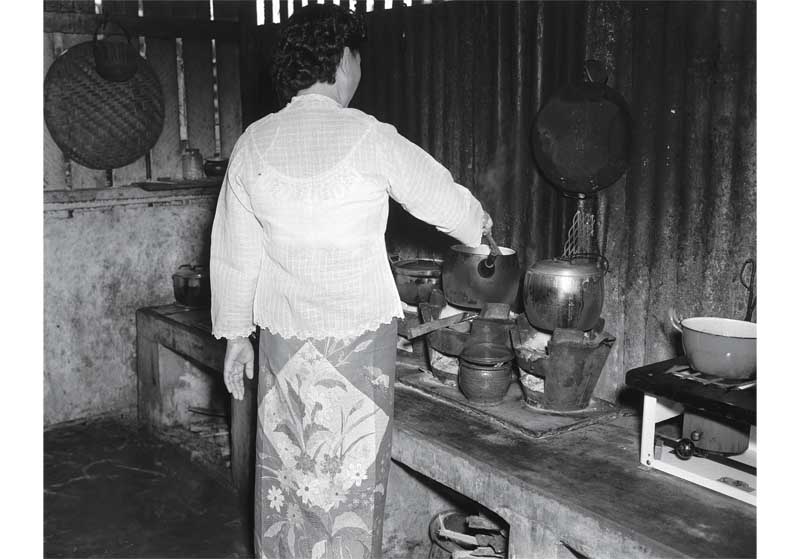

A Nonya lady cooking in her kitchen using firewood. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Nonya lady cooking in her kitchen using firewood. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In the early 1950s, the prices of firewood and charcoal soared, prompting the government to encourage the use of alternative fuel.6 Housewives turned to the kerosene stove,7 but in time it too proved to be a fire hazard.8 The biggest blow to the arang trade was the introduction of cylinder LPG (liquid-petroleum gas) in the 1960s that claimed to “solve all… cooking problems… it lights up at once, … your kitchen will sparkle and shine…”9 As Esso cylinders were briskly delivered to kitchens from the mid-60s onwards,10 tongkangs along Geylang river — custom-made for the charcoal trade — were progressively laid up and scrapped in the 1970s.11

Bidan: Prelude to “Tankee You, Missee”

The bidan kampung (also known as Mak Bidan in Malay, or jie sheng fu in Chinese) — traditional midwives — were once the preferred choice of pregnant mothers. What many bidan lacked in certification they made up with experience. In fact in 1949, more babies were delivered at home in kampungs by rural midwives than at Kandang Kerbau Hospital (KK).12 Families were poor but still continued to have children. In the 1950s, babies were born at the rate of 1,000 a week. 13 Bidans literally lost sleep over this frenzied reproduction, with one bidan confessing in The Singapore Free Press, “Sometimes I’d like to pretend I haven’t heard the bell and turn over and go to sleep… but I never do. I always think of the poor mother waiting for me.”14

The modern bidan or government-trained midwife, fondly called “missy”, surfaced when the colonial government felt that the infant mortality rate was too high and that Singapore needed the guiding hand of western maternity services. The “missy” visited kampungs and co-existed with the bidan. Her trademark was the neat white uniform, but keeping it white was a challenge during her kampung rounds. The sight of a “missy” was often a welcome forebearer of an akan datang (meaning “coming soon”) member to the kampung.

Infant growth assessment carried out by a trained midwife or “missy”, in 1950. School of Nursing collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Infant growth assessment carried out by a trained midwife or “missy”, in 1950. School of Nursing collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Capteh and Other Childhood Games

Many from the kampung generation have fond memories of running riot in the kampong playing games like “police and thief” (or “catching”) and hantam bola (similar to dodgeball). Playtime did not end until sunset when all the kids would disperse and head back home. Sometimes, only the spectre of a sapu lidi (coconut broom) from an exasperated mother shrieking “baaliik!” (“go home” in Malay) was able to break the play marathon.15 When they ran out of money for cheap 10-cent-a-ticket movies, the children would entertain themselves, running amok in the “open sprawling compounds”,16 playing games like capteh.

Capteh is a game known by different names across Southeast Asia. The game requires a light, fit-in-the-palm object called capteh. The base of the capteh was made by stacking a few round pieces of rubber usually taken from an expired bicycle tube, held together by a nail poked through the middle of the rubber. Sprouting from the base would be a bunch of rooster feathers tied with a rubber band. The capteh is tossed up repeatedly using the side of one’s foot while the other remains on the ground. Players competed to see who could do this the most times consecutively without dropping the capteh.17 Capteh games with exceptional players were long drawn — sometimes “… it took the whole of recess hour and… continued the day after or evening after school…”18

Dukus and Durians: The Fruiting Season

Having fruit trees in the house compound was a treat for kampung residents who could freely pick the fruits from the trees. Durians, however, were an exception. As far back as 1936, the durian was already considered an expensive fruit and attracted its fair share of thieves. They would “crawl around the trees in the dead of the night and drag along a large piece of gunny into which the thorns of the durians would stick. By studying the nature of the ground and the circumference of the tree, they could judge the approximate distance a fallen durian would roll…”19

Fruiting seasons were a heady affair that reminded villagers of nature’s bounty: “Life lost its monotony when the countryside resounded with the thud of falling durians and red bunches of luscious rambutans brightened the landscape. All around were trees laden with mangosteens, langsat, rambai, nangka and other seasonal fruits.”20

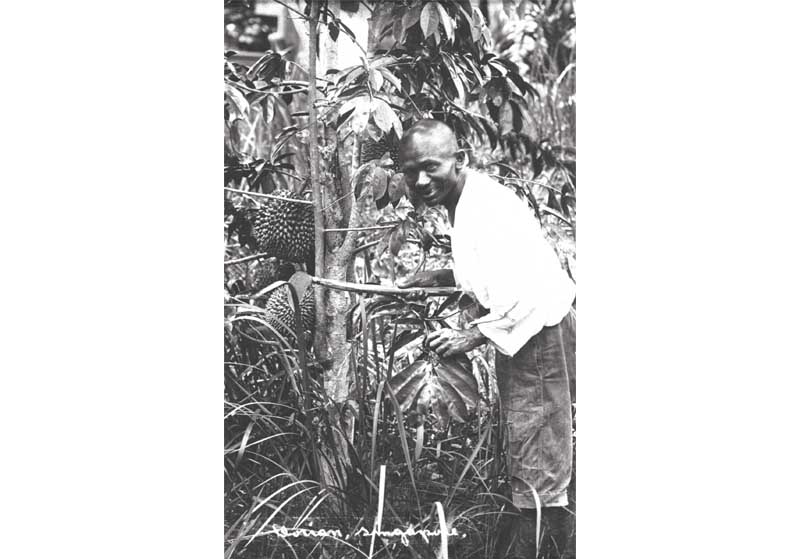

A man at a durian plantation circa 1915. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A man at a durian plantation circa 1915. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Ethnic Enclaves

Stamford Raffles’ demarcation of Singapore’s urban areas into ethnic enclaves took root in the kampungs too with pockets of Chinese huts sited apart from the Malay cluster, often separated by a hillock or a road. It was common to be asked if one came from the kampung cina (Chinese kampung) or kampung melayu (Malay kampung), a distinction borne out by varied housing designs and other cultural markers. The most distinct marker was religion: in a Chinese kampung, the Tua Pek Kong temple devoted to this Taoist deity and the wayang (Chinese opera) stage were crowd-pullers, while in a Malay village, the surau (small mosque) rallied residents for congregational prayers.

Kampung houses were designed to facilitate both easy flow of air for ventilation and neighbourly interaction via open verandas and compounds. The boundaries of each dwelling were usually delineated by natural features such as trees, which meant that the compounds frequently overlapped. This was more typical of the houses in a Malay kampung, whereas houses in a Chinese one usually had a waist-high wooden gate. But there was sufficient visibility around the houses in both types, fostering easy relations and camaraderie that often translated into a strong kampung spirit that did not significantly diminish even in a mixed kampung of Malay and Chinese dwellings. However, each kampung retained its distinct name and way of life.

Often, a common tongue bridged many cultural gaps. In those days, it was common to hear Malay being spoken not just by native speakers.21 Pasar (market) Malay, a colloquial form of the language generously spiced with exclamations of “ayya” and “ayoyo”22 helped smoothed conversations between the two communities.

Five-stones

This was a tossing game, geared towards girls with delicate fingers and usually played sitting cross-legged on the floor. The “stones” — handmade by the girls themselves — were actually small pyramid shaped sachets simply sewn from scraps of cloth and filled with green beans, sand or rice grains. Instead of five, some used seven stones. The game is played by “throwing [the stones] up into the air and catching them back in some form of patterned movements.”23 Each stage has a particular pattern and increases in complexity as the player progresses in the game.

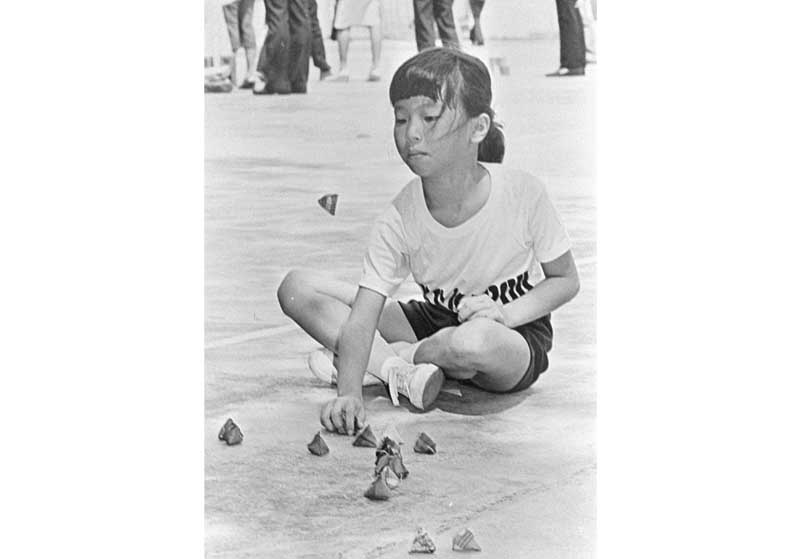

Five Stones is played with five small triangular cloth bags filled with seeds, rice grains or sand (1960s). Singapore Sports Council (SSC) collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Five Stones is played with five small triangular cloth bags filled with seeds, rice grains or sand (1960s). Singapore Sports Council (SSC) collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Goli (Marbles)

It was easy to identify the marble king of a district as he usually strutted around with pockets bulging with his spherical conquests. The earliest marbles were made of clay before they were replaced by glass ones. There were multiple ways to win each other’s marbles and regardless of their luck that day, all would return to the same patch the next day to have another go at the goli galore. It was a game with “lots of arguments and quarrels and fights … But by and large, the next day everybody would turn up again as if nothing happened and start the game [again].”24

Hantam Bola

One of most exhilarating kampung games, hantam (or hentam) bola or rembat bola (whack ball) is a fiercely competitive and physical game. Speed and power reign supreme; players from one team will chase and hit their opponents with a tennis ball as one player described, “I was very good at hantam bola in my younger days, catch tennis ball with left hand and whack anyone in front with the right hand.”

If unlucky, the ball would kena (hit) your face or head (followed by “tao pio ah” or “hit lottery”, a euphemism for being doused on the head with bird poop). Playing hantam bola in the rain would send one rolling into muddy puddles but the fun would end immediately when your mother saw your dirty state; she would hantam (whack) you instead!25,

Itinerant Hawkers: Unlicensed Taste

Street food vendors used to travel from kampung to kampung peddling their signature delicacies. An expectant crowd would gather in anticipation of the tantalising food, such as ice balls, char kway teow (noodles) and satay.26 Unfortunately, the “dirt-cheap” hawker food was often dirt-riddled too.27 In the 1960s, in a move to improve food hygiene, food peddlers were relocated to centralised hawker centres.28

Unlicensed hawkers outside the Jalan Eunos Wet Market in 1958. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Unlicensed hawkers outside the Jalan Eunos Wet Market in 1958. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Jelon

Unlike hantam bola, jelon is played within a set boundary. This game is called galah panjang or hadang-hadang (blocking) in Malaysia but it is known as jelon (a corruption of “balloon”) or belon acah (literally meaning “tease balloon”) in Singapore. When Singaporeans moved to flats, many children played jelon at the void decks or badminton courts. Within those spaces, mini-courts parallel to one another were marked and one team would defend the entrances to these courts. The aim of each team was to penetrate the entrances without getting tapped by their opponents. If one player managed to break through, his team would win, but if one of them got tapped the whole team was out.

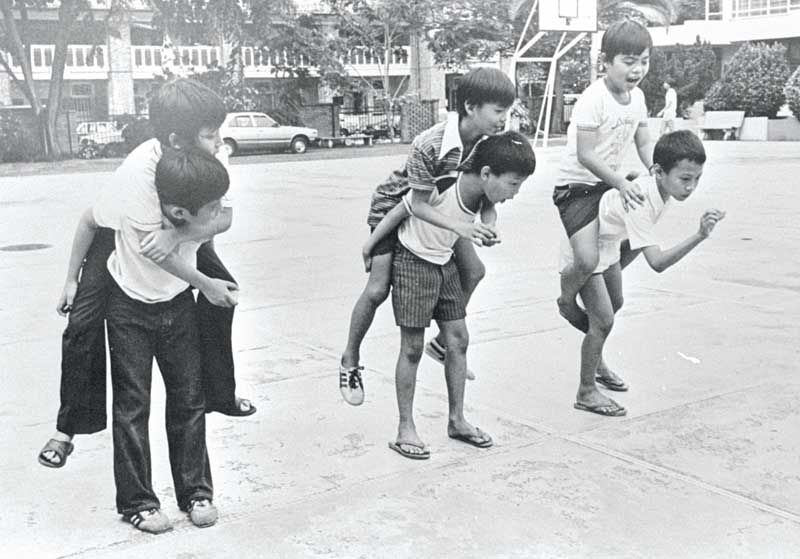

Kleret: He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother

The aim of this game is to get a free piggyback ride from your opponent (pictured below).

Keleret must be played in pairs or teams. Flat stones or tiles (batu keleret) are thrown to get close to the target line or circle (1950s). Courtesy of Singapore Sports Council (SSC) collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Keleret must be played in pairs or teams. Flat stones or tiles (batu keleret) are thrown to get close to the target line or circle (1950s). Courtesy of Singapore Sports Council (SSC) collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Lambong Tin (or “Hide-and-Seek”, “I Spy” or Nyorok-Nyorok)

Prior to the start of the game, a pasang (Malay for catcher) or spy would be selected via oh somm or oh beh som or wah peh ya som (see text box). Next, everyone would gather around and one player would shake a tin that had been filled with stones and then fling it. The moment the tin was flung, everyone would disperse.

The pasang would have to run to the tin and bring it back and shout “I spy!” which signalled that the game had started proper. If players needed a time-out they would signal for a break by making the “peace” sign with their fingers and shout “chope”, “chope night”, or “chope twist”! It would be honoured and everyone could take a break.

Mosquito Buses: Uncontrolled Breeding

The mosquito bus (1920s–1950s) was a form of public transport that appeared about every half hour. The unregulated growth of these buses invited many complaints, particularly about their horn-happy drivers: “[they made] day and night hideous with their incessant horn-blowing (I could, for instance, recognise from my bed no. 425 by his “signature tune” as he went up or down Bukit Timah road.) In those days, it was common for buses to tootle away, while standing at the end of lorongs in Geylang road, in order to inform potential travellers that they were waiting.”29

For all that ruckus, the mosquito buses could only take six seating passengers and one standing. Little wonder that when bigger motorcars appeared, these buses lost their buzz. By the 1950s, they were allowed to ply only in rural areas and the outer fringes of the city.30

Tay Koh Yat bus service’s “Mosquito Buses” at Sembawang (1955). F. W. York collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Tay Koh Yat bus service’s “Mosquito Buses” at Sembawang (1955). F. W. York collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Next-door Neighbours: “No Salt? No Problem!”

Today, when a housewife in the midst of cooking realises she has no salt in her larder, she turns off her gas-powered stove and heads to the nearest grocery store. Decades ago, she would have probably left her arang stove on while she dropped in on her neighbour to borrow some salt. Privacy in kampungs was less guarded as doors or gates were left ajar, inviting interactions and exchanging of small favours. A mother could tumpang (drop) her kids with the next-door neighbour while she ran an errand, or ask her neighbour to pick up some vegetables and fish on her behalf at the market. The gotong-royong (community help) spirit was much alive with neighbours looking out for one another.

Open-air Cinemas = Open Skies Treatment

Children who lived in rural areas were able to enjoy movies thanks to open-air cinemas. It cost 50 cents to secure a (wooden) seat. Many children caught reruns after school and when it rained, people would huddle to the side for shelter. One movie-goer remembered “patronising the cheap open air cinema called Peking Theatre located opposite the present Macpherson market… [movies were only] 5 cents but [one had] to endure the mosquitoes and there were no refunds if the show was cancelled due to heavy rain or power failure.”31

Police and Thief

This game of catch comprises two teams: police who chase and the thieves who flee. A spot would be designated as a prison (to hold “arrested” thieves), usually the trunk of a coconut tree. Thieves would not only be busy running from the police, but also freeing their imprisoned mates by infiltrating the prison and tapping them, though this was not always possible: “The captured thieves would be sitting near the tree waiting for some daring thief to tag them … the tree was tightly guarded … creating an impenetrable fortress … even think Alcatraz [was not] this tough.”32

Queuing at Standpipes

In the days before the convenience of tap water at home, kampung residents had to queue at the common standpipes or wells to draw their water; the worst time for this was in the morning when everyone was getting ready for work or school. After things quietened, the next tranche of users were usually housewives who would crowd around the standpipes to do their washing. Invariably, it was more than just dirt that was swapped as the standpipe also doubled up as the village rumour mill.

Women washing laundry at a common standpipe, circa 1960s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Women washing laundry at a common standpipe, circa 1960s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Rempah and Singapore’s Own Spice Girls

Before there were powdered spices and packaged spice mixes, women used to make their rempah (spice paste) from scratch. They would prepare ingredients such as shallots, lemongrass, garlic and chilli and mix them with dry spices such as coriander seeds, cumin, and cloves. All these would be crushed by stoneware crushers (see “S”) until the ingredients melded into a rempah ready for the frying pan. Rempah is considered the heart and soul of Malay, Eurasian and Peranakan curries and sauces.33

Rempah was freshly made daily and, in the days before home refrigeration, only what was needed was prepared. Such were the standards that went into the making of fish curries, asam pedas (a sour fish curry with pineapple chunks) and spicy sambal concoctions. For ladies whose fingers were too delicate for the hard work, hired hands were always available for about $1.50 a month. In particular, the Kadayanallur Muslim women, who migrated from Tamil Nadu in India, made this their signature trade, making daily home deliveries from house to house carrying baskets of ground spices on their heads. Some of them also sold fresh spice pastes at the wet market, which they ground with a granite rolling pin and a slab.

Stoneware Sisters: Batu Giling and Batu Tumbuk

Before blenders and food processors, stoneware ruled the kitchen and came in a few shapes and sizes. One was a bolster-shaped roller that crushed all kinds of spices on a rectangular slab called batu giling by the Malays. The batu giling’s immovable bulk earned it a fixed place in the kitchen, and perhaps also contributed to its earlier demise than the more portable pestle and mortar, called batu lesung or batu tumbuk. The batu lesung is still used in many Singapore kitchens and traditionalists still swear by the shrimp paste and chilli condiment called sambal belacan it makes. This implement is preferred over its electrical counterparts as it “pulverises by crushing hard ingredients into tiny fragments between two hard surfaces.” It is best for coaxing the fragrant oils from hard spices such as peppercorns, cinnamon bark, cardamom, sesame seeds or coriander, “producing flavours superior to bottled or electric-ground spices.”34

Tarik Upih: The Green F1 Race

The game starts with a child sitting on an upih (dried palm leaf) which is then dragged by his friend with as much speed as he can muster. The team that crosses the finishing line with the “passenger” still on top of the upih wins. Girls, or the leaner ones, almost always enjoyed “priority seating” because it did not pay to have a heavyset player sit on the upih if the team wanted to win. The steeper the slope, the bigger the thrill and the trickier it was to remain on the upih.35

Use-first-pay-later: 555 Notebook

The “555” notebook — with literally these numbers printed on the front cover — was used by businesses to keep a record of customers’ tabs. It was a system built on trust: “When you go [to the provision store], you buy provisions from them… you can just take [items], there’s a little book and then they will write your name, block, your address and all this… And then, [at the] end of the month they will tell you how much you owe them.”36 This handy little notebook also went round the kopitiam and warungs (coffeeshops) taking unpaid orders. At the end of the month however, the “owner would wave the 555 notebook; [a reminder] that the bills had not been settled.” 37

Another debt-reminder that was less pleasant than your sundry shop-owner was the chettiar, or Indian money-lender. Life usually turned bleak after taking a loan from them as come rain or shine, the chettiar would never fail to show up at your doorstep to demand his dues.

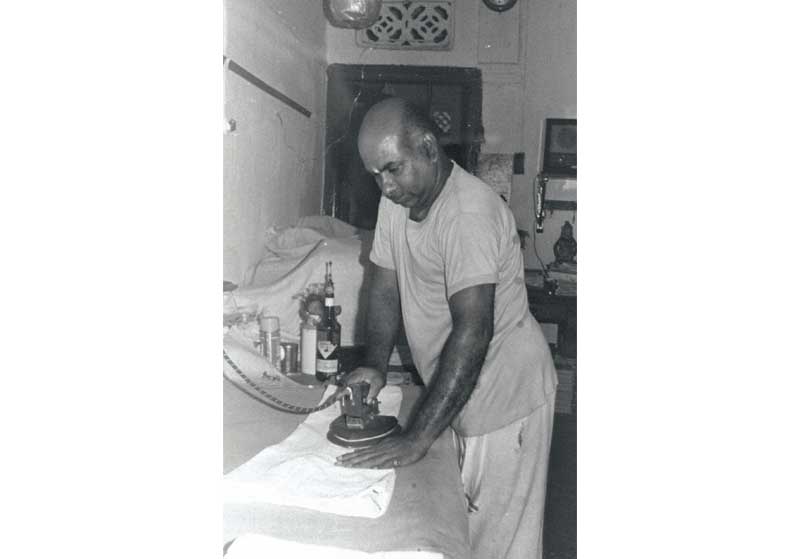

Vanishing Trades: The Bhai of Yesteryears

Several professions were synonymous with men who migrated from India to earn a living in Singapore. For example, the bhai serbat came to Singapore from Uttar Pradesh after the war and dominated the coffeeshop business. Others became laundrymen, security guards or sold chapati (unleavened flatbread).38

Dhobies were laundrymen who eventually had a street named in their honour. In 2005, a dhoby shop, which had retained its “tossing and slapping” washing method, was found still running on St George Road. The owner of the shop, Mr Suppiah, came to Singapore in 1945 as a starry-eyed 15-year-old with big dreams. Life was hard back then as he used to hand-wash up to 500 articles of clothing a day, toiling from eight in the morning to 10 at night.39

The sarabat (original) stallholder or bhai serbat’s signature takeaway was teh sarabat (ginger tea) or teh tarik (pulled tea). The most famous sarabat stalls were those along Waterloo Street opposite the old St Joseph Institution’s football field.40 Another was at Kerbau Road near Serangoon where at a tender age of 12 in the 1960s, Mr Balbeer Singh was already juggling and pulling tea.41 In the laid-back atmosphere of the sarabat stall, Singaporeans from all walks of life met and swapped stories. Even politics was not too grand for the sarabat stall. Kutty Mydeen of the Naval Base Labour Union recalled making an appointment to see lawyer Lee Kuan Yew about the formation of a new political party in the 1950s. Their pre-PAP roundtable talk was just one of the conversations that took place in a sarabat stall one fine morning on Market Street.42

Cattlemen and milkmen were mostly Tamils from South India. Serangoon was a cattle-rearing area in Singapore before the activity was banned in 1936. The Singapore Free Press observed “a herd of 40 or 50 cattle which completely blocked the public thoroughfare [in Victoria Street]. Some of the animals were grazing along the street; others were lying in the centre of the road while the herder, an old Kling man, was comfortably taking a nap on the ground under the shadow of the close hedge of a compound.”43

In the 1930s, the area between Cross Street and New Bridge Road was known as Kampong Susu (milk kampung) and the place lived up to its name from the many Indian milk sellers “identified by a tiny top knot of hair”.44 These Indian milkmen (or bhai jual susu to the Malays) ran door-to-door delivering fresh milk. Sometimes, the cow was milked on the spot: “[The milkmen came] with a cow and people [would] just buy the adulterated or diluted sort of thing. So fresh milk was really fresh…”45

Close-up of Indian dhoby ironing clothes in Serangoon Road (1982). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Close-up of Indian dhoby ironing clothes in Serangoon Road (1982). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Wooden Washboard: The Lean Mean Machine

This slim rectangular wooden block was a dirt-crusher that all housewives swore by to remove stubborn stains. But housewives who spent hours using these boards as they sat around communal standpipes or wells wished they could give it up as it was literally a pain in the neck, back and bottom. The wooden corrugated surface was also hard on the hands, and one could tell the washerwoman’s devotion to this tool from her well-worn hands.

“Xtreme” Disasters: Floods and Fires

Kampungs were subject to frequent flooding that occurred during heavy rainfall. The flood waters often dragged objects in their wake and, once, the residents of Lorong Kinchir were astounded to spot a crocodile in the Kallang River near their kampung after a huge flood – apparently an inmate that had managed to escape from the Lorong Chuan farm.46

Kampungs were also vulnerable to fires due to their wooden and attap structures. The Bukit Ho Swee fire of 1961 is one that is etched in the nation’s consciousness. The famous 19th-century Malay writer Munsyi Abdullah was living in Kampong Glam when it was gutted by a fire in 1847, robbing him of his valuables and letters. The incident so affected the writer that he was moved to pen his now-famous poem “Syair Kampung Glam Terbakar” (Kampong Gelam On Fire) that was published in the same year.47

Yeh Yeh (Zero-point)

Yeh yeh requires a rope that is made by stringing rubber bands together. The aim is to jump over the rope as it is hoisted higher and higher by two other players each holding one end of the rope. At the start of the game, the rope is laid flat on the ground with players exclaiming “zero-point” as they jump over. Players then jump across at increasingly “varying heights beginning with the ankle and ending with the head. To compete further, an ‘inch’ above the head is added. The rule of thumb is no part of [your] body can touch the rubber rope. Once any part of [the] body accidentally touch[es] the rope, the jumper ‘mati’ (‘dies’) and the next person has to jump.”48

Zero-watt Nights: Sleeping with the Enemy

Electricity only reached the kampungs in 1961.49 Before this, residents lit up their nights with kerosene lamps. The absence of electricity in retrospect actually forced people to interact more: “There was no radio or television; and certainly no internet or online gaming to keep one away from others. After dark, the most one could do was to read a book by the glow of a kerosene lamp…”50

However, many unfortunate villagers became victims of fires as a result of accidentally overturning these oil lamps. One such incident was reported in The Straits Times in 1959, where “[a fire] roared through a kampung about 50 yards from the Alexandra road fire station at 1.35 a.m. and destroyed 30 huts housing about 150 people.”51 To stem the hazard, the government introduced the 1963 kampung electricity scheme which promised that all villages would be provided with electricity by 1966.52

OH BEY SOM!

Oh bey som was a means by which teams or individual players were selected. Players would shout “oh bey som!” and simultaneously stick out their hands with their palms facing either up or down. All who had their palms facing in the same direction would be part of one team, and the rest on the other. A player would be singled out to be the pasang (catcher) if he or she was the only person with the palm facing a different direction from the rest of the group. Otherwise, the players would continue to oh bey som, eliminating the majority until a single player remained.

The tajam batu man was usually a Punjabi (Sikh) who made his bicycle rounds in the kampung with his sharp tools. He would call out “tajam batu!”, which literally means “stone sharp(ening)” in Malay. The women would take out their stone slabs that had become too smooth to crush spices for him to service. He would chisel the surface of the slabs with a giant nail and hammer, etching small holes to make the surface rough for better grinding. For some reason, adults would scare children with stories of the tajam batu man kidnapping children, decapitating them and offering their heads for new constructions, bridges in particular. Scenes of scampering children would often precede the arrival of this “devilish” man.

REFERENCES

Teru-teru bozu. (2010, December 4). “Kisah si penajam batu”. Retrieved 2013, October 26 from: http://teruterubozu68.blogspot.sg/search?q=tajam+batu; Nazerin Harun. (2012, June 7). Pemenggal kepala. Retrieved 2013, October 26, from: http://nazerihn.blogspot.sg/2013/06/kepalamanusia-penguat-jambatan.html

A Kadir Jasin. (2010, July 28). “Potong kepala disiplinkan budak-budak desa”. Retrieved 2013, October 26, from http://kadirjasin.blogspot. sg/2010/07/potong-kepala-disiplinkan-budakbudak.html; Nazerin, (2012, June 7) Pememnggal kepala.

This article was researched by Nor Afidah Abd Rahman, a Senior Librarian with the National Library Board (NLB).

REFERENCES

100 charcoal kilns close down. (1951, January 15). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

150 homeless in big kampong blaze. (1959, July 22). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

A Kadir Jasin. (2010, July 28). Potong kepala disiplinkan budak-budak desa. Retrieved from kadirjasian.blogspot.sg website.

Alexander, W. (1956, April 4). Singapore awakes: The first at the standpipe. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

An upcountry tourist in Singapore. (1949, December 31). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ang, J. (1962, August 12). The upstage barbecue. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Aref A. Ghouse. (1999, November 19). ‘Bai serbat’ balik kampong. Berita Harian, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

At Kandang Kerbau. (1950, October 5). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Azlina Rais. (1982, August 12). Bahasa pasar tak patut digalakkan. Berita Harian, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Campbell, W. (1974, March 15). Trading patterns change to keep pace with modern life styles. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chan, K.S. (2001, November 26). Cooking with old king coal. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1984, January 17). Oral history interview with Mabel Martens [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000388/06/02, p. 20]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1985, February 15). Oral history interview with Ronald Benjamin Milne [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000447/64/63, pp. 562, 566]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Chun, S.L. (2008, August 31). More than 1 type of kampong in Singapore. Good Morning Yesterday. Retrieved from Goodmorningyesterday.blogspot.sg. website.

Eastley, A. (1955, June 25). Singapore’s great baby problem. The Singapore Free Press, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Electricity supplies for several kampongs. (1961, October 9). The Singapore Free Press, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Esso cuts price of cooking gas. (1986, May 8). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Farrer, R.J. (1951, November 4). The bygone mosquito buses: Honking horrors. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Feng, Y. (2008, August 9). Makan mash-up. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Firewood. (1940, September 5). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

From huts to high rises. (2007, December 2). The Straits Times, p. 30. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

From tear-jerking to trouble-free cooking. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Fuel important to good cook. (1964, October 28). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Irahhajerah. (2011, May 1). Ingat tak mainan canggih kita zaman kanak-kanak dulu harga dia 20 sen jer? Retrieved from irahhajerah.blogspot.sg website.

Lam, C.S. (2006, October 28). My friend Adrian Chua remembers his childhood days. Good Morning Yesterday. Retrieved from Goodmorningyesterday.blogspot.sg website.

Lee, A. (1985, October 13). From kampong girl to a flat-dweller. The Straits Times, p. 36. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lights for all the kampongs by early 1966. (1965, July 23). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Local. (1850, August 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mohd Yussoff Ahmad (Interviewer). (1990, February 7). Oral history with Mydeen Kutty Mydeen [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001177/05/02, p. 19]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Nazerin Harun. (2012, June 7). Pemenggal kepala. Retrieved from nazerihn.blogspot.sg website.

Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman. (2012, June 1). Then and now: Games children play. iremembersg. Retrieved from iremember.sg website.

Oil stove boom in Singapore. (1951, March 10). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

“Orang Sebarang”. (1936, July 23). And then the durian. Too costly in Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Salmah Semono. (1979, March 4). Pemainan masa lalu jalin ikatan kejiranan. Berita Harian, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Seetoh, K. (2013, May 28). The karipap princess. Retrieved from Makanation website.

Singapore place names and their meanings. (1934, March 19). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Soo, E.J. (2010, August 23). Is the old 555 notebook or the new iPad better. AsiaOne. Retrieve from AsiaOne website.

Suhami Ahmad & Krew Apo2 Yolah. (2012, March 14). Zaman hingus meleleh. Retrieved from anaknegori.blogspot.

Suppiah, P. (2005, January 20). A clean break? Not yet. Today, p. 30. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Syair Kampung Gelam Terbakar. Melayu Online. Retrieved from Melayu Online website.

Tan, C.H. (Interviewer). (2007, April 26). Oral history interview with Bryan Richmond [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003155/03/01, p. 23]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Tan, S., & Tay, M. (2003). World food: Malaysia & Singapore (p. 51). Australia: Lonely Planet. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Teh tarik dan jambatan bawa nostalgia masa silam. (1990, June 9). Berita Harian, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tengok tu macam tak ada pape. (2012, October 16). Retrieved from Facebook.com.

Teru-teru bozu. (2010, December 4). Kisah si penajam batu. Retrieved from teruterubozu68.blogspot.sg website.

The Chinese bus companies. (1950, June 6). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The unborn give her no peace. (1950, October 28). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

When hundreds of hawkers are using them. (1971, November 23). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ye Ye Orh…sajer. (2009, April 16). Zero point. Retrieved from Percicilan.wordpress.com website.

NOTES

-

Alexander, W. (1956, April 4). Singapore awakes: The first at the standpipe. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ang, J. (1962, August 12). The upstage barbecue. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chan, K.S. (2001, November 26). Cooking with old king coal. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Firewood. (1940, September 5). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 26 Nov 2001, p. 16. ↩

-

100 charcoal kilns close down. (1951, January 15). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oil stove boom in Singapore. (1951, March 10). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

When hundreds of hawkers are using them. (1971, November 23). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fuel important to good cook. (1964, October 28). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

From tear-jerking to trouble-free cooking. (1964, March 7). The Straits Times, p. 3; Esso cuts price of cooking gas. (1986, May 8). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Campbell, W. (1973, March 15). Trading patterns change to keep pace with modern life styles. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

At Kandang Kerbau. (1950, October 5). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Eastley, A. (1955, June 25). Singapore’s great baby problem. The Singapore Free Press, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The unborn give her no peace. (1950, October 28). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Suhami Ahmad & Krew Apo2 Yolah. (2012, March 14). Zaman hingus meleleh. Retrieved from anaknegori.blogspot. ↩

-

Lee, A. (1985, October 13). From kampong girl to a flat-dweller. The Straits Times, p. 36. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Salmah Semono. (1979, March 4). Pemainan masa lalu jalin ikatan kejiranan. Berita Harian, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1985, February 15). Oral history interview with Ronald Benjamin Milne [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000447/64/63, p. 566]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

“Orang Sebarang”. (1936, July 23). And then the durian. Too costly in Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Jul 1936, p. 1. ↩

-

Chun, S.L. (2008, August 31). More than 1 type of kampong in Singapore. Good Morning Yesterday. Retrieved from Goodmorningyesterday.blogspot.sg. website. ↩

-

Azlina Rais. (1982, August 12). Bahasa pasar tak patut digalakkan. Berita Harian, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ye Ye Orh…sajer. (2009, April 16). Zero point. Retrieved from Percicilan.wordpress.com website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Ronald Benjamin Milne, 15 Feb 1985, p. 562. ↩

-

Tengok tu macam tak ada pape. (2012, October 16). Retrieved from Facebook.com website. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1984, January 17). Oral history interview with Mabel Martens. [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000388/06/02, p. 20]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

An upcountry tourist in Singapore. (1949, December 31). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Feng, Y. (2008, August 9). Makan mash-up. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Farrer, R.J. (1951, November 4). The bygone mosquito buses: Honking horrors. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Chinese bus companies. (1950, June 6). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lam, C.S. (2006, October 28). My friend Adrian Chua remembers his childhood days. Good Morning Yesterday. Retrieved from Goodmorningyesterday.blogspot.sg website. ↩

-

Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman. (2012, June 1). Then and now: Games children play. iremembersg. Retrieved from iremember.sg website. ↩

-

Tan, S., & Tay, M. (2003). World food: Malaysia & Singapore (p. 51). Australia: Lonely Planet. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Tan, L.L. (1983, February 19). Use that mortar and pestle. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Irahhajerah. (2011, May 1). Ingat tak mainan canggih kita zaman kanak-kanak dulu harga dia 20 sen jer? Retrieved from irahhajerah.blogspot.sg website. ↩

-

Tan, C.H. (Interviewer). (2007, April 26). Oral history interview with Bryan Richmond [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003155/03/01, p. 23]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Soo, E.J. (2010, August 23). Is the old 555 notebook or the new iPad better. AsiaOne. Retrieve from AsiaOne website. ↩

-

Aref A. Ghouse. (1999, November 19). ‘Bai serbat’ balik kampong. Berita Harian, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Suppiah, P. (2005, January 20). A clean break? Not yet. Today, p. 30. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Seetoh, K. (2013, May 28). The karipap princess. Retrieved from Makanation website. ↩

-

Teh tarik dan jambatan bawa nostalgia masa silam. (1990, June 9). Berita Harian, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mohd Yussoff Ahmad (Interviewer). (1990, February 7). Oral history with Mydeen Kutty Mydeen [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001177/05/02, p. 19]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Local. (1850, August 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore place names and their meanings. (1934, March 19). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral interviews. National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Chun, 31 Aug 2008. ↩

-

Syair Kampung Gelam Terbakar. Melayu Online. Retrieved from Melayu Online website. ↩

-

Ye Ye Orh…sajer, 16 Apr 2009. ↩

-

Electricity supplies for several kampongs. (1961, October 9). The Singapore Free Press, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

From huts to high rises. (2007, December 2). The Straits Times, p. 30. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

150 homeless in big kampong blaze. (1959, July 22). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lights for all the kampongs by early 1966. (1965, July 23). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩