From Here to Eternity: Archiving and Immortality

Kevin Khoo considers the link between memory, immortality and archiving, and what this means for the National Archives of Singapore.

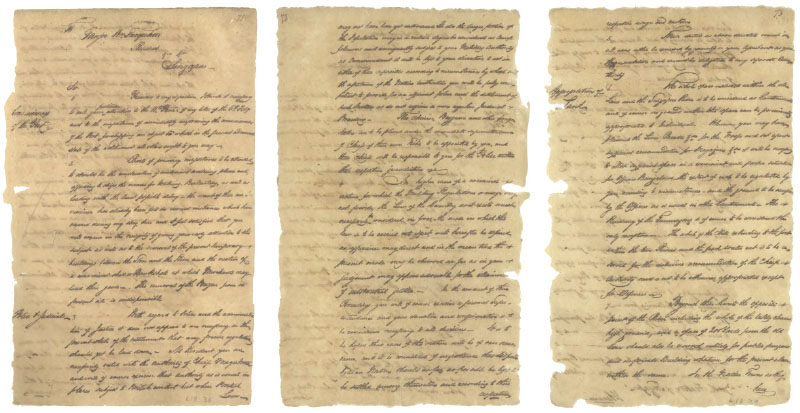

Selected pages from Sir Stamford Raffles’ original instructions to Sir William Farquhar for the development of Singapore Town, 25 June 1819.1 Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Selected pages from Sir Stamford Raffles’ original instructions to Sir William Farquhar for the development of Singapore Town, 25 June 1819.1 Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Man is immortal; therefore he must die endlessly. For life is creating idea; it can only find itself in charging forms.

Immortality — the idea of living eternally, never aging, dying or being forgotten — has captivated mankind throughout history. Humans — as sentient beings gifted with intellect, self-awareness and creativity, capable of love and the capacity to conceive and perceive infinity, yet bound by mortal bodies which invariably age and die — have always sought an escape from this inevitable fate.

Mankind has sought immortality in a variety of ways, the most obvious being physical immortality. Rooted in the joys of mortal life and the fear of oblivion at death, this form of immortality — to be forever youthful and deathless — remains a goal of medical science and has found expression in contemporary popular culture, with its morbid fascination for vampires, who live forever, albeit at a terrible cost.2 Indeed the pursuit of physical immortality, perhaps for its hubris and overreach, has a history closely intertwined with morbidity. One recalls the Chinese Emperor Qin Shih Huang’s attempts to prolong his life by consuming mercury pills, which instead led to his insanity and premature death,3 as well as the grim Greek legend of Tithonus, a handsome youth for whom the goddess Eos procures immortality. But she forgets to ask for enduring youth, and Tithonus degenerates into a withered object of horror, longing to die but unable to.4

Immortality is also at the heart of many religions and forms of spirituality — whether Platonic, Abrahamic, Buddhist, Confucian, Hindu or Taoist — in the notion of an immortal soul that survives the death of the physical body and continues in an afterlife as a spirit, or in a reincarnated body or a glorified resurrected body — depending on one’s belief. Immortality in such instances is never questioned either because of one’s firsthand interaction with immortal beings or a personal conviction that such supernatural beings exist, whether as spirits, angels, or God Almighty. As the reasoning goes — since immortals exist, and because humanity has the means to relate with them, immortality is possible. But such immortality is at best intangible because it is experienced in another place and time.

Immortality and Memory

More tangible is the idea of immortality gained through memory, in the remembrance and recollection of human accomplishments, recorded permanently in the annals of history. Here “one lives in the hope of becoming a memory” as the Argentine poet Antonio Porchia said. Recollection gives one’s achievements permanence far beyond a mortal life, creating a legacy and freeing one’s work from the futility inherent in most human activity, to be forgotten soon after it is accomplished. Today, we still recall and honour the works and deeds of people such as Aristotle, Alexander the Great, Newton, Lao Zi, Shakespeare, Paul of Tarsus and Pythagoras centuries and even millennia after their deaths. But how many remember a news article (or worse, an email) written the last year, or perhaps even last week?

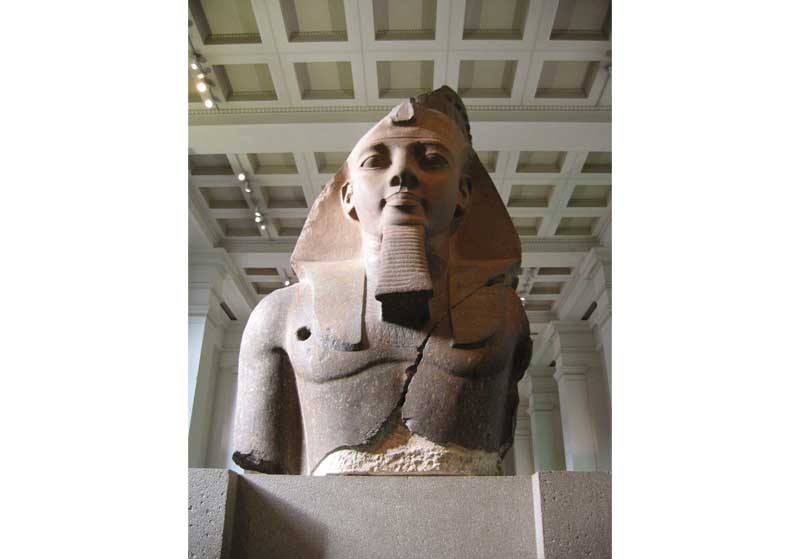

As memory is probably the most plausible way for man to attain a measure of immortality in this world, it has encouraged many to strive to realise excellences that merit recalling. Yet the paradox is that while an achievement might be personal, the process of recollection and recognition depends on the ones who remember. For unless others actually choose to remember, the memory of one’s achievement invariably dies. Rulers, seeking immortality, have erected vast monuments to commemorate the achievements of their reigns. But such efforts are typically futile if there is no general and voluntary consensus corresponding with the self image of those in power. Shelley’s haunting poem, “Ozymandias” comes to mind:

I met a traveler from an antique land / Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone / Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, / Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, / And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command… / And on the pedestal these words appear: / “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: / Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” / Nothing besides remains. Round the decay / Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare / The lone and level sands stretch far away.5

Thus most fundamentally, one’s “immortality” rests on the acclaim and recognition by others. Memory cannot be forced, and immortality is not something won by mere dictate or design.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was inspired by the imminent arrival of this colossal fractured statue of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II (image via Wikimedia Commons6) in London to write his poem “Ozymandias” in 1818. The statue was acquired by the British Museum and remains a centrepiece of the museum.7

Percy Bysshe Shelley was inspired by the imminent arrival of this colossal fractured statue of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II (image via Wikimedia Commons6) in London to write his poem “Ozymandias” in 1818. The statue was acquired by the British Museum and remains a centrepiece of the museum.7

Archiving and Immortality

An archive is in effect a repository of memory — of records of legal, historical and cultural significance, generated and organised in the course of business or social transactions across the lifetime of individuals and organisations. As a primary function of an archive is to safekeep records that have been appraised and deemed worthy of preservation, documents selected for an archive’s permanent collection acquire — by extension — a form of immortality. Archives form a select corpus of records that allow people to reconstruct and understand events that have occurred in past times. As archived records are carefully safeguarded to preserve their provenance — or their original form and context — they have been accorded a special value by researchers and historians since ancient times.

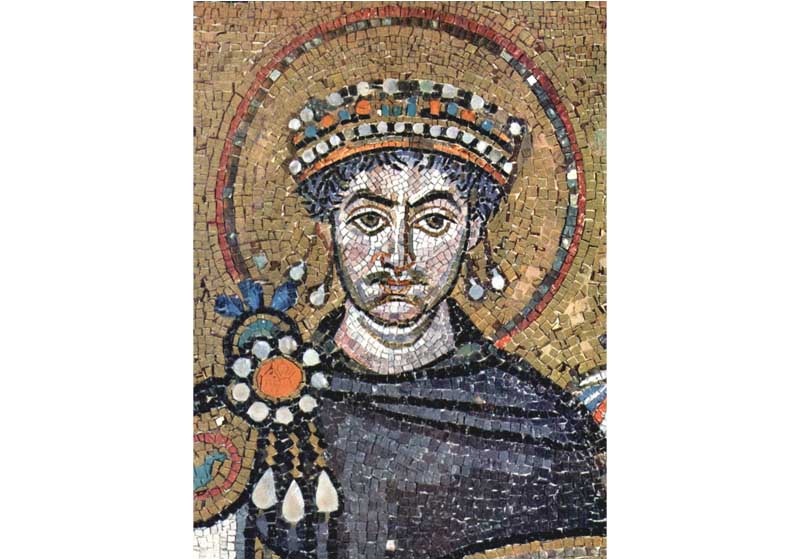

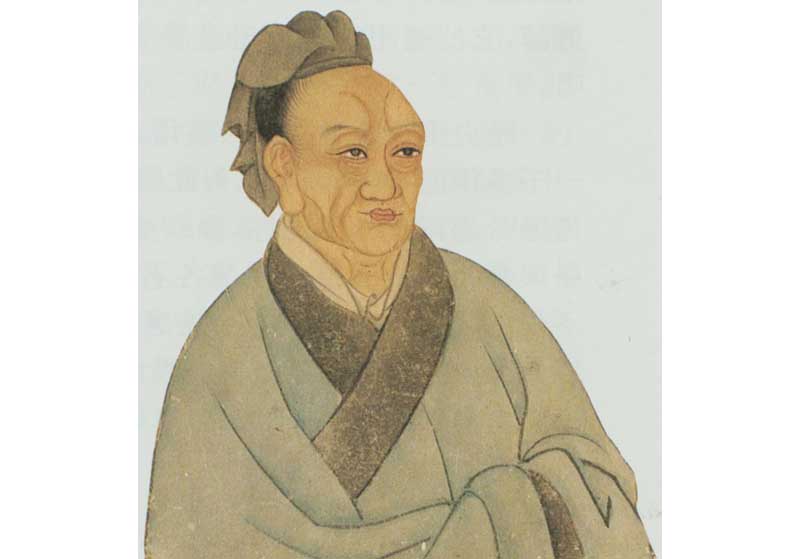

As records — “frozen in time” as it were — properly archived documents have a basic trustworthiness relative to other sources. Such archived documents can impart a lasting quality to works based on them. An example of this is the Justinian Code or “Corpus Juris Civilis”. Commissioned in 6th century CE by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, the Code was based on centuries of carefully archived Roman legal precedents and remains the basis of much European civil law till today.8 Another example is the Historical Records of the Grand Historian Sima Qian, the famed court historian of the Han Dynasty. Written in the 1st century BCE, his work drew heavily on the Han imperial court archives and remains a classic and reliable resource on ancient Chinese history to this day.9

Mural depiction of the Emperor Justinian who ruled between 527–565 CE at the height of the Byzantine Empire's influence. Image via Wikipedia Commons.

Mural depiction of the Emperor Justinian who ruled between 527–565 CE at the height of the Byzantine Empire's influence. Image via Wikipedia Commons.

Painting of Sima Qian, who served as court historian during the Han Dynasty between 145/135–86 BCE. Image via Wikipedia Commons.10

Painting of Sima Qian, who served as court historian during the Han Dynasty between 145/135–86 BCE. Image via Wikipedia Commons.10

For all its impressive possibilities in relation to immortality, a notable feature of an archive is that it may contain many records that are not monumental. While treasures can be found in most state archives — iconic documents such as the English Magna Carta (1215), the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America (1776), and here in Singapore, records such as the letters of Sir Stamford Raffles and the Singapore’s own Proclamation of Independence (1965) — a large part of archived records are more operational and administrative in nature. At the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), one finds alongside records on key decisions and policy-making, documents on school attendance, marriages, cemetery records, applications for licences, appeals for wage increases, and other records that might be considered routine in nature.

Yet, routine records can be of great practical and historical importance. And not infrequently, it is such routine records that help historians immortalise a period in writing. For example, because property and taxation records established legal obligations vital to governing populous and geographically widespread states like Imperial Rome and China, historians have used these records to address questions such as how government was organised and the relationship between state and society at the time.

Highly operational records, such as lighthouse maintenance and administrative records, meteorological records, immigration control records, as well as shipwreck salvage permits and accident reports are examples of archives used in Singapore’s successful defense of its sovereignty over the island of Pedra Branca at the International Court of Justice in 2008. Singapore’s legal team was able to reconstruct from such routine records how Singapore had administered the island and its waters for a long time.11 Another notable and innovative application of seemingly routine archives was how social historian James Warren used coroner records to understand the way of life, diet and disease common to rickshaw pullers in pre-war Singapore.12

Many modern archives also have growing collections of photographic and audio-visual records that capture everyday scenes in which historical changes in aesthetics, mannerisms, technology and others aspects of material culture are captured in a highly evocative form. As the famed British archivist Sir Hilary Jenkinson put it — because routine records are created as a by-product of everyday actions, and were not consciously produced “in the interest or for the information of posterity” they ironically can become some of the best sources for telling us, with relative impartiality and naturalness, things as they actually happened in the past.13, 14

Immortality is a concept fraught with paradoxes. As far as physical immortality remains impossible, it implies a non-material existence which extends beyond mortal life; the continuation of a personality beyond death (whether in spirit or on record), and the retention of its capacity to influence this world however disembodied. The idea has pre-scientific roots, but retains a hold on a popular culture that is increasingly dominated by empirical studies and science. Immortality is granted to people and events that merit remembering, but also, as reflected in the contents of an archive, it is given to things which may have had no intention or conscious desire of being remembered.

An image of Orchard Road circa 1900s when its surroundings were mostly spice and fruit plantations. This is a far cry from Orchard Road today (ABOVE), which is a highly urbanised and chic shopping belt. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore and Kevin Khoo, respectively.

An image of Orchard Road circa 1900s when its surroundings were mostly spice and fruit plantations. This is a far cry from Orchard Road today (ABOVE), which is a highly urbanised and chic shopping belt. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore and Kevin Khoo, respectively.The National Archives of Singapore (NAS) houses the collective memory of the nation, which allows current and future generations of Singaporeans to understand its different cultures, explore its common heritage and appreciate who we are as a people and how we became a nation.

As the official custodian of the corporate memory of the government of Singapore, NAS manages public records and provides advice to government agencies on records management. From government files, private memoirs, historical maps and photographs to oral history interviews and audio-visual materials, NAS is responsible for the collection, preservation and management of Singapore’s public and private archival records, some of which date back to the early 19th century.

NAS protects the rights of citizens by providing evidence and accountability of government actions. Its repository of archival materials makes NAS an important research centre for those in search of information about the country’s history. NAS also promotes public interest in Singapore history and heritage through educational programmes and exhibitions.

Kevin Khoo is an archivist at the National Archives of Singapore. He is a historian by training, and alumni of the National University of Singapore’s History Department. His interests include cultural and social history, comparative religion, philosophy, literature and poetry, economics and archival science.

REFERENCES

British Military Administration (BMA). (1945, October–December). Estimates of revenue and expenditure for 1946 [Microfilm no.: NA 1309]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Bullfinch, T. (2004). Bullfinch’s mythology: The age of fables or stories of Gods & heroes. New York: Modern Library Paperbacks. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Duranti, L. (1994, Spring). The concept of appraisal and archival theory. American Archivist, 57 (2), 328–344. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Freedman. P. (2011, Fall). The reign of Justinian – the early middle ages: 284-1000 AD [Yale Open courses]. Retrieved from Yale University website.

Gollner, A.L. (2013, August 19). Live forever, can science deliver immortality. Salon Magazine. Retrieved from salon.com website.

Housel, R., & Wisnewski, J.J. (2009). Twilight & philosophy: Vampires, vegetarians and the pursuit of immortality. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved from OverDrive. (myLibrary ID is required to access this ebook)

Jayakumar, S., & Koh, T. (2009). Pedra Branca: The road to the world court. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. (Call no.: RSING 341.448095957 JAY)

National Archives (Singapore). (2011). Records management handbook: Creating, appraising, disposing and preserving public records. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 025.1714095957 REC)

Posner, E. (1972). Archives in the ancient world. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Raffles, S. (1819, June 25). Original instructions to William Farquhar on the Plan of Singapore Town. Straits Settlements Records. Series L, Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen [Straits Settlement Records, L10]. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore (Microfilm no.: NL57)

Shelley, P.B. (1818). The complete poetic works of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Vol. 2). Ozymandias, Retrieved from The Literature Network online website.

The British Museum. (2013). Statue of Ramesses II, the “younger memnon’. Retrieved from the British Museum website.

Warren, J.F. (2003). Rickshaw coolie: A people’s history of Singapore, 1880–1940. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. (Call no.: RSING 388.341 WAR)

Watson, B. (1958). Ssuma Ch’ien: Grand historian of China. New York: Columbia University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Wright, D.C. (2011). The history of China. California: Greenwood Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

NOTES

-

Raffles, S. (1819, June 25). Original instructions to William Farquhar on the Plan of Singapore Town. Straits Settlements Records. Series L, Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen [Straits Settlement Records, L10]. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore (Microfilm no.: NL 57) ↩

-

Housel, R., & Wisnewski, J.J. (2009). Twilight & philosophy: Vampires, vegetarians and the pursuit of immortality. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved from OverDrive. (myLibrary ID is required to access this ebook) ↩

-

Wright, D.C. (2011). The history of China. California: Greenwood Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Bullfinch, T. (2004). Bullfinch’s mythology: The age of fables or stories of Gods & heroes. New York: Modern Library Paperbacks. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Shelley, P.B. (1818). The complete poetic works of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Vol. 2). Ozymandias, Retrieved from The Literature Network online website. ↩

-

Image of Ramesses II Bust: Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; With no invariant sections, no Front-Cover texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled GNU Free Documentation License. ↩

-

The British Museum. (2013). Statue of Ramesses II, the “younger memnon’. Retrieved from the British Museum website. ↩

-

Freedman. P. (2011, Fall). The reign of Justinian – the early middle ages: 284-1000 AD [Yale Open courses]. Retrieved from Yale University website. ↩

-

Watson, B. (1958). Ssuma Ch’ien: Grand historian of China. New York: Columbia University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Image of Emperor Justinian: The work of art depicted in this image and the reproduction thereof are in the public domain worldwide. The reproduction is part of a collection of reproductions compiled by The Yorck Project. The compilation copyright is held by Zenodot Verlagsgesellchaft mbH and licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. Image of Sima Qian: This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to Australia, the European Union and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 70 years. ↩

-

Jayakumar, S., & Koh, T. (2009). Pedra Branca: The road to the world court. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. (Call no.: RSING 341.448095957 JAY) ↩

-

Warren, J.F. (2003). Rickshaw coolie: A people’s history of Singapore, 1880–1940. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. (Call no.: RSING 388.341 WAR) ↩

-

Duranti, L. (1994, Spring). The concept of appraisal and archival theory. American Archivist, 57 (2), 328–344. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

British Military Administration (BMA). (1945, October–December). Estimates of revenue and expenditure for 1946 [Microfilm no.: NA 1309]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩