Spies, Virgins, Pimps and Hitmen: Singapore Through the Western Lens

Western filmmakers have always had a fascination for Singapore. Ben Slater tells you why.

Singapore (1947) is a romance set in Singapore but shot in a Hollywood studio. © Singapore. Directed by John Brahm, produced by Jeremy Bresler, distributed by Universal Studios. United States, 1947.

Singapore (1947) is a romance set in Singapore but shot in a Hollywood studio. © Singapore. Directed by John Brahm, produced by Jeremy Bresler, distributed by Universal Studios. United States, 1947.

While Singapore’s own film industry has thrived and collapsed and then risen again, the history of foreign film production, particularly that of filmmakers from Europe and America making movies in and about the island is a long and fascinating one. This history is a reflection of the way Singapore has transformed over the last 50 years as well as changing perceptions of Singapore in the West.

The First Films

In the early 1930s, Frank Buck – the self-promoting Texan showman and exotic animal “collector” – pitched up in Singapore with a small film crew to shoot a version of his bestselling memoir Bring ‘Em Back Alive (1932), re-enacting scenes of tigers and elephants being captured in their natural habitat. It was a huge success and spawned several sequels. Singapore, as depicted by Buck, contrasted the untamed wilderness of the jungle with the colonial sophistication of the Raffles Hotel. The result was a compelling myth of tropical Asia that was eagerly consumed by American film audiences.

At around the same time, Ward Wing, a bit-part American actor turned director, arrived in Singapore to make Samarang (variously known as Semarang, Out of the Sea and Shark Woman). Touted as a “jungle adventure” for American audiences and shot on a shoestring budget, it starred two Caucasian expatriates (an English policeman and an Armenian beauty queen) and was scandalous for its prurient depiction of harmless tribesfolk as semi-naked cannibals. Whereas Buck’s films were quasi-documentaries, Wing was the first Western filmmaker to shoot a narrative film in Singapore – albeit one that he took much artistic licence with. Inevitably, Wing’s impulse was to exoticise and misrepresent Singapore. Still, 80 years later, we can view Samarang as a sublime documentary – the faces and behaviour of the extras, as well as the now forgotten landscapes indelibly captured on celluloid before they disappeared.

In travelling to Asia as filmmakers, Wing and Buck were pioneers. During this period, and well into the post-war era, “tropical Singapore”, as Hollywood depicted it, was conjured up with stock footage and studio recreations of dark alleys, sleazy bars and jungle roads. (Many of these early Hollywood films purportedly set in Singapore never came within sniffing distance of the island.)

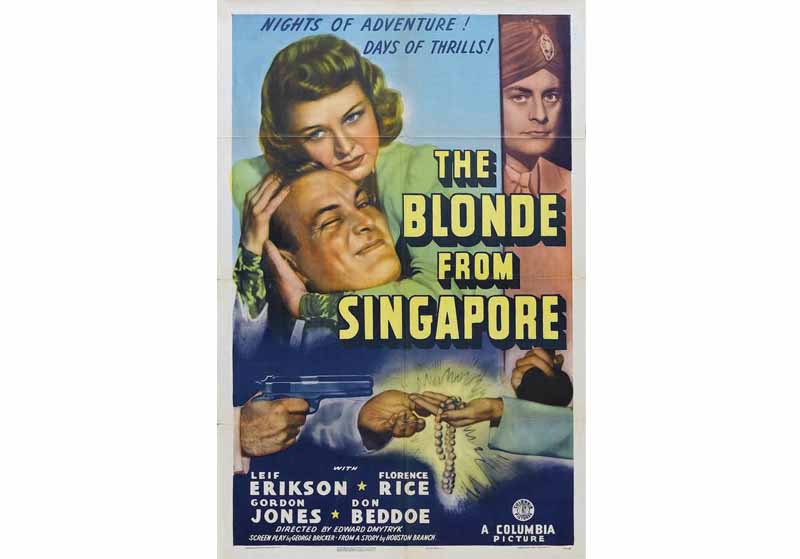

This fabricated Singapore was the perfect setting for Hollywood melodramas and thrillers concerning desperate souls set adrift in inhospitable foreign climes. The lovers in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rich and Strange (1931), for instance, wind up in Singapore briefly, as do the heroes and femme fatales of Night Cargo (1936), The Letter (1930), adapted from a famous story by Somerset Maugham, The Blonde from Singapore (1941) and Singapore (1947), a loose remake of Casablanca that features Ava Gardner speaking Malay! This cycle of “Singapore noir” films reached its apotheosis with Robert Aldrich’s explosive and bleak World for Ransom (1954), made using leftover sets (and actors) from the low-budget TV adventure series entitled China Smith, also set in our ersatz Lion City.

The Blonde from Singapore (1941) is an adventure romance filmed in Hollywood. © The Blonde from Singapore. Directed by Eward Dmytryk, produced by Jack Fier, distributed by Columbia Pictures. United States, 1941.

The Blonde from Singapore (1941) is an adventure romance filmed in Hollywood. © The Blonde from Singapore. Directed by Eward Dmytryk, produced by Jack Fier, distributed by Columbia Pictures. United States, 1941.

The Spying Sixties

From the 1960s, as Singapore gained independence and modernised rapidly, foreign film crews became commonplace, their arrival coinciding with the decline of the local film industry. Low-budget filmmaking was flourishing in the US and Europe, successful genres were quickly copied and exploited, and the “production value” provided by shooting in exotic foreign places more than made up for the price of long-distance air tickets (which were quite affordable at the time) and the effort of hauling over equipment and people.

A number of European B-movies were shot partially in Singapore in the 1960s, mostly “super-spy” films – knock-offs of the James Bond genre. After all, international travel was as essential to the genre as gadgets, beautiful women and submachine guns. While Bangkok, Hong Kong and Tokyo were visited by 007 himself, a motley crew of European filmmakers descended at then Paya Lebar Airport to shoot their versions of the Bond film.

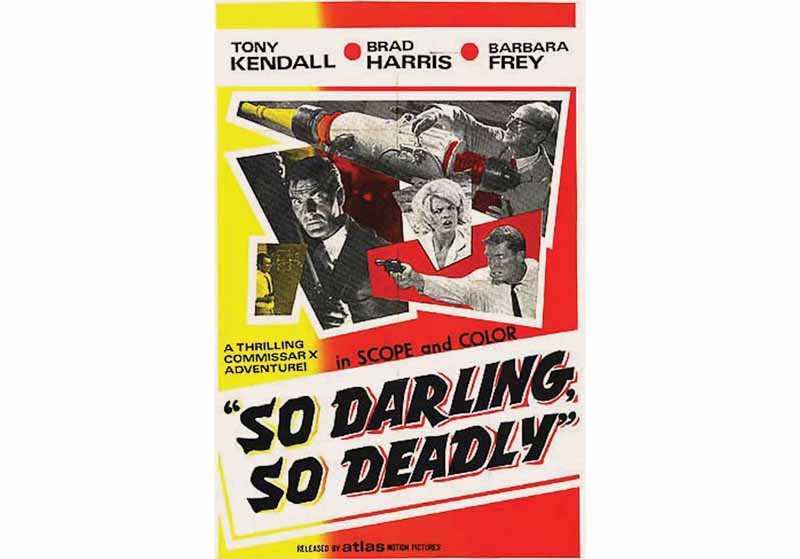

The hero of So Darling So Deadly (1966) is Agent Joe Walker (also known as the Kommissar X), an American spy-cum-detective film based on a series of German pulp fiction in this mostly Italian production starring American B-lister Tony Kendall and body-builder-turned-actor Brad Harris as his sidekick. The plot is ludicrous guff about atomic secrets (echoed in all of these spy films), but it is beautifully filmed and almost entirely shot on location in Singapore and Johor (including a delightful chase through kitschy Haw Par Villa in Pasir Panjang).

This was followed by another Italian spy-flick, Goldsnake: Anonima Killers (1967), drastically less stylish and amusing than So Darling So Deadly, although it affords rare glimpses of a 1960s Orchard Road, among other locations in Singapore. Arguably the best of these films is Five Ashore in Singapore (1967), a French guys-on-a-secret-mission picture starring Sean Flynn and Dennis Berry, the offspring of Hollywood greats Errol Flynn and John Berry, respectively. The street scenes capture Singapore in the midst of celebrating its first National Day (the film was shot around August 1966), and in photographing the texture of street life, the camera crew seem to be far more curious about filming the scenery of Singapore than the violent gang of “heroes” who stomp, kick and shoot their way around the island with brutal indifference to their surroundings. But the worst was yet to come.

In late 1969, a Hong Kong-based American photographer and newsreel cameraman, Marvin Farkas, raised just enough money to make a spy thriller in Singapore. The premise for the film came from two Singapore-based war correspondents, Keith Lorenz and Ian Ward, who had aspirations to write a movie that captured an explosive moment in Southeast Asia (Vietnam and Indonesia were blowing up – literally; President Suharto had just come into power in Indonesia, and Vietnam was in the thick of a bloody war between the north and south). After some false starts, the inexperienced Farkas hired New Yorker Joel Reed to rewrite and helm his picture. Due to desperation, a fast-depleting budget and sheer expediency, the film, entitled Wit’s End, became a laughable excuse for brawls, car chases, terrible acting, gratuitous nudity and overblown homophobia. After more or less disappearing upon completion, it was (nonsensically) retitled G.I. Executioner in the 1980s. Incredibly, the film had the support of Singapore’s Cathay-Keris Films and the Ministry of Culture, an indicator of how keen Singapore was to court foreign films.

So Darling So Deadly (1966) is an American spy movie that was filmed on location in Singapore. © So Darling So Deadly. Directed by Gianfranco Parolini, produced by Hans Pflügler. United States, 1966.

So Darling So Deadly (1966) is an American spy movie that was filmed on location in Singapore. © So Darling So Deadly. Directed by Gianfranco Parolini, produced by Hans Pflügler. United States, 1966.

The “Hollywood” Years

In fact, Hollywood did come calling in the late 1960s, initially via two British (but American studio-backed) productions, both adapted from literary sources. Pretty Polly (1967) was a big-budget romantic drama adapted from an acidic Noel Coward short story set in Singapore. Its shoot around town caused enormous excitement due to the presence of teen megastar Hayley Mills in the title role, alongside Bollywood king Sashi Kapoor as a Singapore tour guide Amaz, who doubles up as a gigolo. Although the film was a huge flop and has never been released in Singapore, it remains a fascinating depiction of the island as a hedonistic playground for swinging grown-ups (there is a long sequence filmed in the Bugis Street of yesteryear), and where Mills experiences sexual and romantic liberation.

The other Hollywood production from this time also tells the tale of a young visitor gaining a worldly education from a “native”. The Virgin Soldiers (1969) is a faithful adaptation of Leslie Thomas’ poignant autobiographical novel about his experiences as a bored recruit stationed in Singapore during the post-war Malayan Emergency (the armed conflict between the British and local Communists guerrillas between 1948 and 1960). Young soldier Brigg (Hywel Bennett) loses his virginity to and falls for Chinatown girl “Juicy” Lucy (Tsai Chin), but the tedium of Singapore eventually erupts into violence, bringing their dalliance to an end. Both Pretty Polly and The Virgin Soldiers deal with the aftermath of the colonial era, the sun setting on the British Empire, and the growing tension between locals and their former colonial masters-turned-interlopers.

The local press gave wide coverage to these films and reported how Singapore benefited from the presence of these productions. Tom Hodge, general manager of Cathay-Keris (which provided production support to these films), was frequently quoted as being optimistic about Singapore’s future as an Asian outpost for Hollywood. But this bubble was about to burst.

The next American film due to be shot in Singapore was meant to be the biggest yet. Oscar-winning film director Frederick Zinnemann had planned to adapt André Malraux’s novel Man’s Fate with Singapore standing in for Shanghai. Millions of dollars were spent on pre-production, locations were selected, local actors cast and crew hired, but at the last minute, in 1969, MGM, the studio that commissioned the film, pulled the plug on the film. It was a financial disaster and an embarrassment for MGM and Singapore, and although in no way the latter’s fault (the film was just too expensive for the studio), it appeared to cool Hollywood’s interest in the Lion City and vice versa. A number of other studio productions slated to be filmed in Singapore, including an adaptation of James Clavell’s Tai Pan, starring Patrick McGoohan, were similarly cancelled.

In 1978 it looked as if things would change. Singapore was all abuzz over the arrival of the stars and production crew of Hawaii 5-0, one of the biggest TV shows in the world, to shoot two episodes in town. Simultaneously, journalists reported that Hollywood wunderkind director Peter Bogdanovich was also in town scouting locations for a film called Jack of Hearts. In actual fact Bogdanovich was already in the process of surreptitiously shooting what would turn out to be the infamous Saint Jack. The subsequent story of how, according to the press, Bogdanovich had “cheated” Singapore in order to make his less-than-flattering portrayal of the republic, overshadowed the merits of the film. Saint Jack (1978) would be banned in Singapore for nearly 30 years, and almost certainly made the powers-that-be cautious about granting permission to foreign films crews.

Saint Jack was a controversial movie filmed on location in Singapore and banned for nearly 30 years. © Saint Jack. Directed by Peter Bogdanovich, produced by Hugh M. Hefner and Edward L. Rissien, distributed by New World Pictures. United States, 1978.

Saint Jack was a controversial movie filmed on location in Singapore and banned for nearly 30 years. © Saint Jack. Directed by Peter Bogdanovich, produced by Hugh M. Hefner and Edward L. Rissien, distributed by New World Pictures. United States, 1978.

Transformative Times

During the 1980s, Singapore’s popularity as a film location declined. The old cinematic city, with steamy jungles, crumbling mansions, derelict shophouses and bustling streetlife, was now dominated by brand new skyscrapers, high-rise housing blocks and cleaned-up streets. In achieving Western-style modernity, Singapore had lost some of the charms and exotica that originally drew Western film companies to its shores.

There were sporadic TV productions, mainly from Australia (World War II miniseries Tenko and Tanamera – Lion of Singapore were partially shot on location) as well as the American TV movie Passion Flower (1986) starring Bruce Boxleitner and Barbara Hershey. Passion Flower is a glossy contrast between sensual, incense-infused Chinatown and the cold, high-tech towers of Shenton Way and sets the scene for a world of sexual and financial deceit played out between two expatriates in Singapore. Amusingly, Raffles Hotel is recast as the lavish office of a cruel billionaire and a few “locals” with speaking parts are depicted as mere pawns in the highstakes game.

For the next few years, there would be no major foreign film productions set in Singapore until James Dearden’s Rogue Trader (1999). Ewan McGregor starred as Nick Leeson, the real-life broker who brought about the collapse of Barings bank on the Singapore Stock Exchange in the mid-1990s. Despite being thoroughly dull, and only partly shot on location (the exchange floor was recreated in a London studio), Rogue Trader is significant in that it contains no trace of the usual Orientalist clichés that Western filmmakers are wont to portray about the island city. The film depicts the modern, cosmopolitan Singapore of condominiums, bars (along Boat Quay), cafés and restaurants, where the British protagonists mingle with their Singaporean friends (and not just other expats).

More recently, London-based Irish directors Joe Lawlor and Christine Molloy made the feature Mister John (2013) in Singapore. The film takes a fresh look at the archetypal tale of the Western visitor in the tropics. Gerry (Aidan Gillen) arrives in Singapore to attend his brother’s funeral while escaping from a troubled marriage back home. He becomes attracted to his sibling’s Singaporean widow (played by Zoe Tay in a rare English film appearance), while moving through a nocturnal world of girlie bars, cheap hotels and karaoke lounges. On one hand Singapore is presented as erotic and mysterious (with hints of the supernatural and some lush jungle locations), but at the same time, it is also an ordinary place where people (both foreigners and Singaporeans) work through their struggles.

Hollywood’s Return

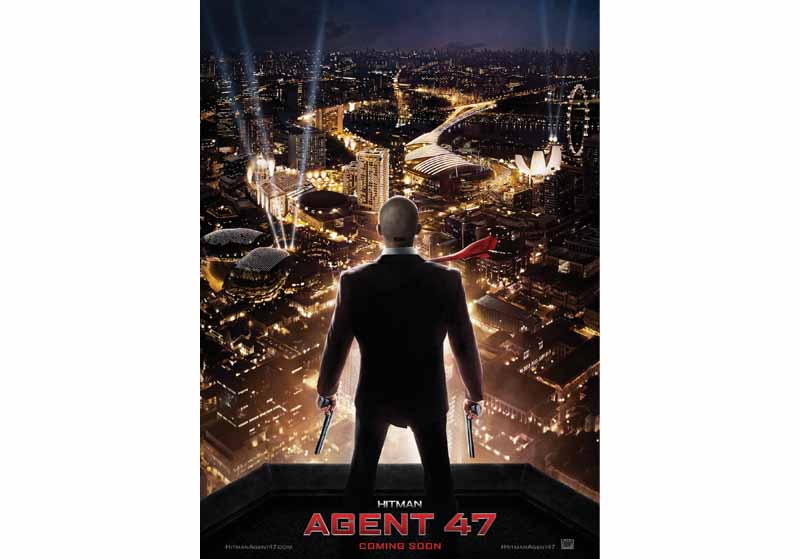

In 2014, two high-profile films were shot partially in Singapore and are due for release in 2015: Hitman: Agent 47, a second attempt to adapt the action videogame franchise to film, features Singapore as a backdrop to some kinetic mayhem, while Equals, a sci-fi thriller starring Nicholas Hoult and Kristen Stewart, was shot on location in both Singapore and Japan. As the Agent 47 trailer and poster make abundantly clear, Singapore is now sought after for its ultra-futuristic cityscapes. Interestingly, the famously prolific producer Roger Corman, who visited the Saint Jack set in 1978, had casually mentioned to one of the local crew that Singapore would be a perfect place to make a science fiction film. It seems, over 30 years later, that he was right.

The soon-to-be released Hitman: Agent 47 was partly filmed on location in Singapore. © Hitman: Agent 47. Directed by Alek Sander Bach, produced by Adrian Askarieh, Alex Young and Charles Gordon, distributed by 20th Century Fox. United States and Germany, 2015.

The soon-to-be released Hitman: Agent 47 was partly filmed on location in Singapore. © Hitman: Agent 47. Directed by Alek Sander Bach, produced by Adrian Askarieh, Alex Young and Charles Gordon, distributed by 20th Century Fox. United States and Germany, 2015.

SAINT JACK: A NEW TAKE ON SINGAPORE

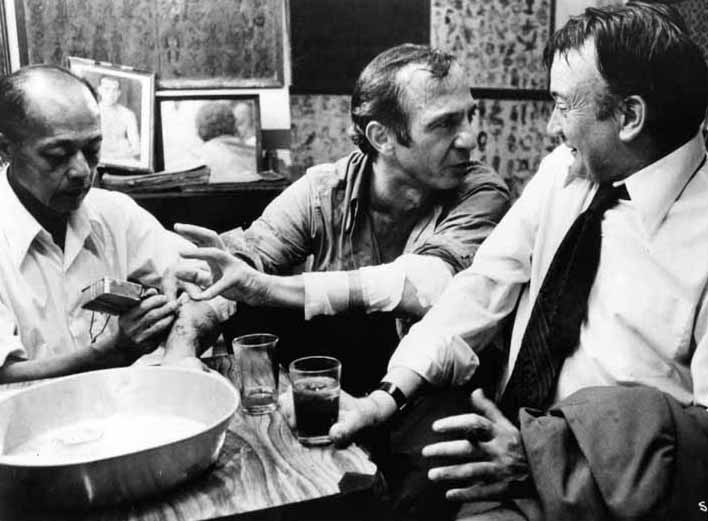

Adapted from the novel by Paul Theroux (who taught English Literature at the University of Singapore from 1968 to 1971), Saint Jack featured another white man cutting loose in the Lion City. But Jack Flowers, a ships chandler and pimp, portrayed by Ben Gazzara in the film, represented a more nuanced protagonist. Flowers is an “old hand” who slips with ease between the expatriate circle and the local world, with Singaporeans who become his friends, colleagues and lovers (and who have substantial roles in the film – another first). The film – shot entirely in Singapore between May and June 1978 – was banned because of its “negative portrayal” of the island, but in fact has a deeper interest and understanding of Singapore than any previous foreign production. Flowers may bitterly complain about Singapore in the film, and memorably tells a drunken, ironic version of the legend of how Sang Nila Utama named the island Singapore, but he is also clearly very fond of his adopted home. Bogdanovich counts Saint Jack as one of his favourites among the many great films he made, and over the years has repeatedly regretted that the film is not better known. His experience in Singapore was “life-changing”, and his most recent film, She’s Funny That Way (2015), about a man who falls in love with a prostitute, is a clear reworking of ideas he developed for Saint Jack.

Ben Gazzara (Jack Flowers) getting a tattoo while co-star Denholm Eliot looks on in the film Saint Jack. © Saint Jack. Directed by Peter Bogdanovich, produced by Hugh M. Hefner and Edward L. Rissien, distributed by New World Pictures. United States, 1978.

Ben Gazzara (Jack Flowers) getting a tattoo while co-star Denholm Eliot looks on in the film Saint Jack. © Saint Jack. Directed by Peter Bogdanovich, produced by Hugh M. Hefner and Edward L. Rissien, distributed by New World Pictures. United States, 1978.

Ben Slater is the author of Kinda Hot: The Making of Saint Jack in Singapore (Marshall Cavendish: 2006), a contributing writer to World Film Locations: Singapore (Intellect: 2014) and the editor of 25: Histories & Memories of the Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF: 2014). He is also the co-screenwriter of the feature film Camera (2014) and a lecturer at the School of Art, Media and Design at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU). His 10-film season of foreign films made in Singapore, “Beyond Saint Jack”, is currently underway at the NUS Museum. See http://malayablackandwhite.wordpress.com for details.

REFERENCES

Millet. R. (2006). Singapore cinema. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL)

Slater, B. (2006). Kinda hot: The making of Saint Jack in Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 791.430232 SLA)

Toh, H.P. (2015). The hunter: Location scouting in Singapore’s filmic history. Retrieved from sgfilmhunter.wordpress.com website.

Uhde, J., & Udhe, Y.N. (2010). Latent images: Film in Singapore. Singapore: Ridge Books. (Call no.: RSING 384.8095957 UHD)