The Art of Movement: Dance on the Singapore Stage

Tara Tan profiles five trailblazers of the Singapore dance scene who have pushed the envelope and created a unique Singaporean dance identity.

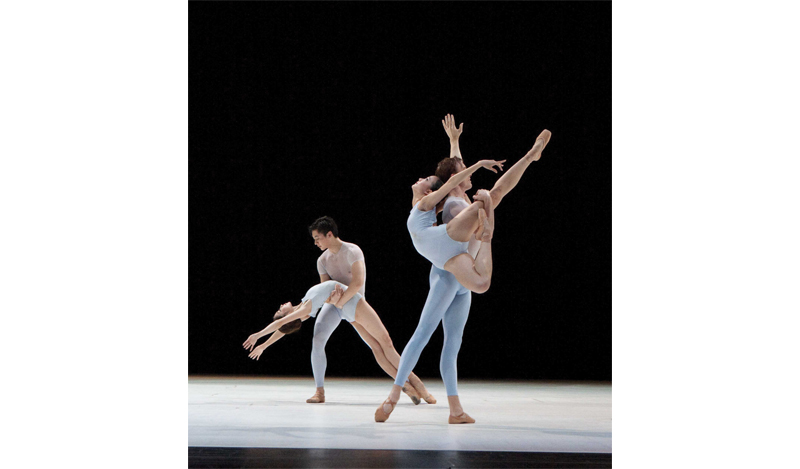

Dancers from the Singapore Dance Theatre take on contemporary ballet hits such as Finnish choreographer Jorma Elo’s Glow-Stop. Courtesy of Singapore Dance Theatre.

Dancers from the Singapore Dance Theatre take on contemporary ballet hits such as Finnish choreographer Jorma Elo’s Glow-Stop. Courtesy of Singapore Dance Theatre.

“The strange thing about all these gestures, these angular, sudden, jerky postures, these syncopated inflexions formed at the back of the throat, these musical phrases cut short, the sharded flights, rustling branches, hollow drum sounds, robot creaking, dances of animated puppets, is that: through the maze of gestures, postures, airborne cries, through their gyrations and turns, leaving not even the smallest area of stage space unused, the meaning of a new bodily language no longer based on words but on signs emerges.”

It was in 1931 when influential French director Antonin Artaud sat, enraptured, in a Parisian theatre watching Balinese dancers perform a trance ritual. With their angular postures and purposeful gestures, Artaud described the dancers as “living hieroglyphics”. The dance, to him, spoke a language that transcended human speech.

Since the body is its very instrument of expression, dance, by nature, carries with it fluency in cultural and ethnographic affiliations. Just as our psyche is moulded by our environments, our body language is shaped by the socio-political and economic landscapes in which it inhabits. A simple gesture, say, a thumb touching the inside of a middle finger, could carry the same meaning across many diverse Asian cultures – it is often read as a sign for a flower – but not necessarily to Western audiences more accustomed to ballet. Like language, dance carries its own nuances and symbolism, its own emotional attachments and historical significance.

Singapore, a young nation with layers of multicultural complexity, finds the internal debate manifested in its various art forms. Balancing a duality between Western influence and Asian roots, for instance, is a sociological struggle in post-colonial Singapore, and is a common trope in much of its local art. This is perhaps more evident in a spoken art form like theatre, where even the delivery of lines on stage – whether it be Singlish or “proper English” (typically Anglicised accents peppered with American slang) – can incite debate on nationalism and identity. A similar dialectic, perhaps less publicly discussed, exists within the cultural polemic of dance on the Singapore stage, where the socio-cultural discourse might be silent, but certainly, not invisible.

The Language Dance in Singapore

As a country of immigrants, the roots of dance in Singapore naturally stem from its major ethnic groups – Malay, Chinese, Indian and Eurasian. Dance groups and schools such as Malay folk dance troupe Sriwana and classical Indian dance school Bhaskar Arts Academy were prominent in Singapore’s arts and education scene from the 1960s to the 1980s. Some of the most influential dance practitioners at the time included contemporary ballet dancer Goh Lay Kuan, Malay dance doyenne Som Said, classical Indian dancer Santha Bhaskar, and classical ballerina Goh Soo Khim.

The 1990s saw the arrival of an increasingly affluent and cosmopolitan Singapore. At the first annual Festival of Dance (the predecessor to the Singapore Arts Festival) in 1982, arts audiences in Singapore were treated to touring performances by the world’s dance greats, including offerings as varied as the Nederlands Dans Theater of the Netherlands, Taiwan’s Cloud Gate Dance Theater and the famed Russian ballet troupe, Bolshoi Ballet.

Interest in dance grew, and with it the question: What is the Singaporean dance identity? It likely straddles the canonical halls of Western ballet and centuries-old Asian dance traditions. As an artist living in a diverse and multi-ethnic country such as Singapore, it is only natural to be influenced by the many cultures of its inhabitants. By some sort of osmosis, their culture, inevitably becomes part of yours.

“Watching Chinese dance, Malay dance, has completely influenced my choreography,” said classical Indian dancer Santha Bhaskar in an interview in 2010.1 Drawing inspiration from these traditions, she has woven part of these cultures into her own choreography, while still staying true to Bharatanatyam, the classical South Indian dance form she practises.

Similarly, Kuik Swee Boon, the Singapore Dance Theatre alumni who founded T.H.E. Dance Company, used his ballet background to establish a foundation for a new type of lingua franca. In As It Fades (2011), he paid tribute to the fading heritage of Chinese dialects such as Teochew, Hainanese and Cantonese with expressive choreography using “complex floorwork and powerful lunges”. In a 2011 review for The Straits Times, I described the movements as being “symbiotic and tightly woven, the ebb and flow between steps reminiscent of taiji”.

The work, while heavy in its balletic stylistics, was infused with flavour that was distinctively and unmistakably Asian. It was a “compact and masterful ode, a poetic homage to traditions and the erosions wrought by time”.2

How do we forge a dance identity that we can call our own? How do we balance the influences of both Eastern and Western cultures, paying homage to both but subservient to neither? The journeys of these five trailblazers in dance will shed some light on the evolving language of the Singapore stage, and in the process, perhaps reveal some human insight into the struggle of the Singaporean identity.

T.H.E Dance Company's Bedfellows (2013) was part of T.H.E's 5th anniversary celebrations, choreographed by Kuik Swee Boon, Lee Mun Wai and Yarra Ileto. Courtesy of Matthew G. Johnson.

T.H.E Dance Company's Bedfellows (2013) was part of T.H.E's 5th anniversary celebrations, choreographed by Kuik Swee Boon, Lee Mun Wai and Yarra Ileto. Courtesy of Matthew G. Johnson.

“The Red Ballerina”

Goh Lay Kuan, The Theatre Practice Ltd

Spirited dance doyenne Goh Lay Kuan pushed boundaries not just in dance, but the politics governing 1970s Singapore. Dubbed “The Red Ballerina” by the press, Goh and her late husband, theatre playwright and director Kuo Pao Kun, were arrested under the Internal Security Act in 1976 and detained without trial on suspicion that they had communist affiliations due to the politically-charged nature of their work. Some of their pieces, like Gai Si De Cang Ying (Damn the Fly), raised sensitive issues about socio-political issues in Singapore.

Dancer Goh Lay Kuan, dubbed “The Red Ballerina”, left her mark on both art and society. Courtesy of The Theatre Practice Ltd.

Dancer Goh Lay Kuan, dubbed “The Red Ballerina”, left her mark on both art and society. Courtesy of The Theatre Practice Ltd.

Born in Sumatra, Indonesia, in 1939, Goh left for Singapore as a child and discovered a love for dance. Inspired by fellow classmates Goh Soo Khim and Goh Choo San, siblings who came from a family of dancers, she enrolled as a classical ballerina at the Victoria Ballet Guild in Melbourne, Australia. In 1964, Goh returned to Singapore to set up the Singapore Performing Arts School in 1965 with her newly-wed husband, Kuo Pao Kun. The school was renamed Practice Theatre School in 1973 and has undergone several name changes over the years, most recently in 2010 to The Theatre Practice Ltd.

“We did everything ourselves, including the stage set and costumes. I didn’t get a salary for 13 years, only money for transport. We took 17 years to pay our debts,” Goh revealed in an interview with The Straits Times in 2014.3 With the school set up, Goh hoped to groom a new stable of dancers and artistes. In 1965, she choreographed her first piece, Flower, Youth, Sea, a contemporary ballet piece with strong Malay influences.

Singapore’s political tensions, however, threw a spanner in the works. Under suspicion of communist leanings, the couple were interrogated and detained under the Internal Security Act. While Goh was released a few months later, Kuo was detained for four-and-a-half years. “We had raised issues about children and their poverty, sometimes in songs, short plays, or on stage… We did not make any direct criticism but they thought we had a communist ideology,” said Goh in the same interview.4

By the mid-1980s, the couple had been exonerated of any wrongdoing, and the pro-communist allegations against them were dropped. In 1983, Goh studied under famed contemporary dancer and choreographer Martha Graham in New York. In 1988, she created Nu Wa — Mender of the Heavens (1988) for the Singapore Festival of Arts, which came to be recognised as Singapore’s first full-length modern dance production. Based on Chinese mythology, Nu Wa encapsulated Goh’s artistic tensions between her Asian roots and Western ballet training. For her significant contributions to Singapore’s dance scene, Goh was conferred the Cultural Medallion for dance in 1995.

“She so successfully blended contemporary, East Asian, and Southeast Asian dance forms and themes such that, even if one may discern traces of ballet, and Indian, Malay and Chinese dances, her final form was none of those: it was, simply, a dance choreographed by Goh,” said Venka Purushothaman in his 2002 book on Cultural Medallion recipients.5

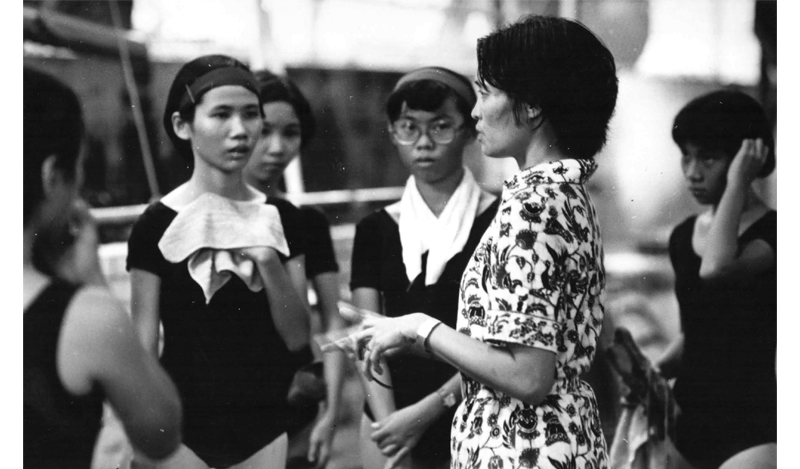

A young Goh Lay Kuan at the first ballet class she taught at the Practice Theatre School. Courtesy of The Theatre Practice Ltd.

A young Goh Lay Kuan at the first ballet class she taught at the Practice Theatre School. Courtesy of The Theatre Practice Ltd.

Three Generations of Dance

Santha Bhaskar, Bhaskar’s Arts Academy

Arriving in Singapore in 1959 from Kerala, India, the then 15 year-old-dancer had no idea what to expect from her arranged marriage to K. P. Bhaskar, a man she had never met. All she knew was that he ran a small dance school in Singapore, Bhaskar’s Arts Academy. “As soon as my plane touched down on the runway, I saw the smiling faces of Mr Bhaskar, students and friends. I didn’t feel homesick. Not even for a second,” said Santha Bhaskar.6 As a wide-eyed ingénue to bustling Singapore, she started learning more about Malay and Chinese cultures. She recalled, “When I first came, I didn’t know how Chinese faces looked like, or Malay faces looked like. I’d never seen people eat with chopsticks before!” The learning evolved from food – arguably the heart and soul of Singapore – to her passion for dance.

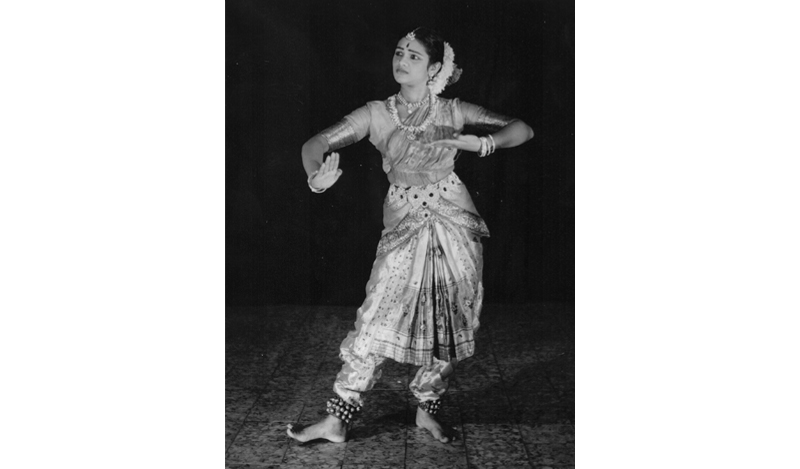

A young Santha Bhaskar performing to a Tamil poem for a function organised by Tamil Murasu held at the Victoria Theatre in 1957. Courtesy of Santha Bhaskar.

A young Santha Bhaskar performing to a Tamil poem for a function organised by Tamil Murasu held at the Victoria Theatre in 1957. Courtesy of Santha Bhaskar.

As artistic director of Bhaskar’s Arts Academy, where she teaches Bharatnatyam dance, Bhaskar began exploring her newfound insights. Weaving Chinese, Malay and even Thai dance influences into her dance choreography, Bhaskar has staged key Asian works such as the classic Chinese folktale Butterfly Lovers (1958), as well as the Thai mythology Manohra (1996).

From the 100 students the academy had in the 1950s, the dance school has more than 2,000 today. Bhaskar is also artistic director and resident choreographer of NUS Indian Dance at the Centre for the Arts at the National University of Singapore, where she taught for over 20 years since the late 1970s.

At the Centre for the Arts, Bhaskar also dabbled in dance forms such as hip-hop and contemporary dance as well as literary arts like poetry. For instance, the light-hearted dance drama Pappadum featuring hip-hop dance group NUS Dance Blast! was staged in 2006, while Vibrations, an experimental meld of Indian dance with light and video, was performed at Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay the following year. In 2012, Chakra, which combined Indian dance movements with sand art, was staged.

“My artistic inspirations grew with Singapore. Watching Chinese dance, Malay dance and international dance forms has influenced my choreography,” said Bhaskar.7

Even with the new influences, there still remains a strong sense of tradition, especially in this household of dance with three generations of dancers. “What I learnt from my mother, my teacher, I taught to my daughter, who taught it to her daughter. In a way, that becomes tradition,” Bhaskar said.8 She was awarded the Cultural Medallion for her work in dance in 1990.

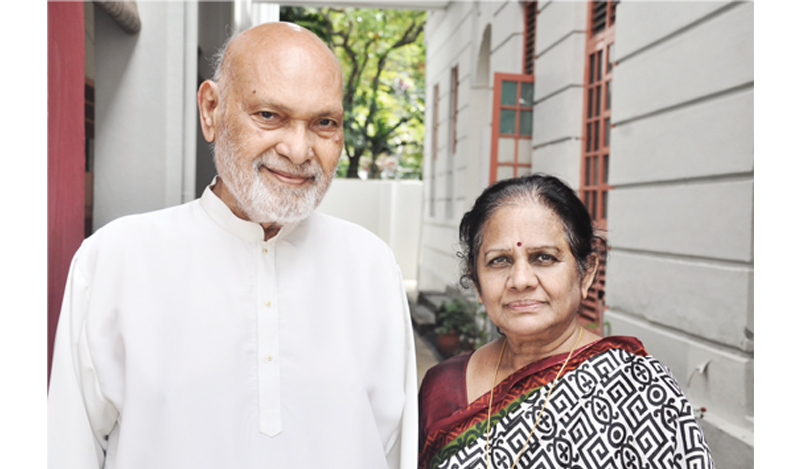

Santha Bhaskar with her late husband K. P. Bhaskar. Courtesy of Santha Bhaskar.

Santha Bhaskar with her late husband K. P. Bhaskar. Courtesy of Santha Bhaskar.

A Family Affair

Som Mohamed Said, Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts

Dancer and entrepreneur Som Mohamed Said is one of the most recognisable names in Malay dance in Singapore today. Starting her dance career at Sriwana, one of Singapore’s pioneer dance troupes, she spent three decades there, eventually rising to the position of artistic director. At the same time, she also ran a thriving Malay wedding business. In 1997, with funds saved from her bridal company, Som Said founded Singapore’s first fully professional Malay dance company, Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts.

Som Mohamed Said is a pivotal force in the Malay dance scene. Courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initiative of Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.

Som Mohamed Said is a pivotal force in the Malay dance scene. Courtesy of Tribute.sg, an initiative of Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.

A pivotal force in the Malay dance scene, Som Said has spoken out about the need for Singapore to develop its own approach to Malay dance and an identity it can call its own, instead of blindly following classical Indonesian traditions. With her performing arts troupe, she began to create and choreograph works that wove traditional Malay dance routines with contemporary moves and multicultural elements. Some of her most frequent collaborators are Indian dancer Neila Sathyalingam and Chinese dancer Yan Choong Lian, who co-created pieces like The Dance Harmony and Singapore City Lights.

“I am a traditional person but my tradition is not static – you can create and still hold on to tradition,” said Som Said in an interview with The Straits Times.9

Her peer Osman Abdu Hamid, artistic director at Era Dance Theatre, commented that Som Said pushed boundaries in traditional Malay dance. “Not much of Malay dance used floor-level movement, such as rolling on the floor,”10 he pointed out.

Som Said’s works often revolve around stories, legends and folk tales from the Malay Peninsula, such as Tun Fatimah (1989) and Bangsawan in Dance (1998).

Today, Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts is one of the most prolific Malay dance companies in Singapore, having performed in over 40 international events and 30 local productions in the past 18 years. The troupe has 25 performing artistes and is currently managed by Som Said’s son, Adel Ahmad. Som Said received the Cultural Medallion for dance in 1987.

Spot the multicultural influences in the costumes and props of Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts. Courtesy of Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts.

Spot the multicultural influences in the costumes and props of Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts. Courtesy of Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts.

Chasing Dreams

Kuik Swee Boon, T.H.E. Dance Company

One of the youngest, but most high-profile dance companies on the Singapore scene today is T.H.E Dance Company, which stands for The Human Expression Dance Company. Started by Singapore Dance Theatre’s former principal dancer Kuik Swee Boon in 2008, the troupe is known for fusing Asian and local identities with ballet techniques in high-impact and contemporary dance performances.

After a five-year stint as principal dancer at the world-renowned Spanish dance company Compania Nacional de Danza in Madrid, Kuik returned to Singapore in 2007 and started T.H.E. Dance Company a year later. Gathering a stable of young dancers, he began to forge a new identity in the Singapore dance scene by staging ambitious and emotionally charged works that drew inspiration from societal issues and human emotions.

Kuik’s first full-length work, Old Sounds, was commissioned by the National Heritage Board in 2008. It was a meditative piece about the slow eradication of Chinese dialects in contemporary city life. Featuring folk songs and snippets of conversations in dialect, the dancers moved in sweeping curves and fleet-footed steps against a multimedia backdrop of music and film.

As It Fades (2011) was another seminal work in T.H.E’s repertoire. In an ambitious move, Kuik chose to stage it at Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay, a grand venue that no other dance company apart from the Singapore Dance Theatre, had performed at before. Paying homage to Asian traditions and culture, the piece juxtaposed contemporary dance movements with Hainanese folk songs.

To groom new talents in dance, Kuik set up T.H.E. Second Company to nurture the next generation of dancers. He also started Contact, an annual dance festival to showcase budding Asian dancers and choreographers. Kuik was conferred the Young Artist Award by the National Arts Council in 2007.

Kuik Swee Boon, who leads the contemporary dance group T.H.E. Dance Company, takes the leap in Within, Without. Courtesy of Tan Ngiap Hen.

Kuik Swee Boon, who leads the contemporary dance group T.H.E. Dance Company, takes the leap in Within, Without. Courtesy of Tan Ngiap Hen.

The Grand Dame of Dance

Singapore Dance Theatre

The Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT) is Singapore’s first and most established classical ballet troupe. Founded in 1988 by Goh Soo Khim and the late Anthony Then, the illustrious dance company rose from humble beginnings. At its first official performance in 1988 at the Singapore Festival of Arts, the SDT had only seven dancers – three Singaporeans, three Filipinos and one Malaysian. Today, the dance company has more than 30 full-time dancers and apprentices in its fold.

Best known for its classical ballet repertoire, which includes classics such as Anna Karenina, The Nutcracker and Cinderella, the SDT has also staged works by acclaimed choreographers such as André Prokovksy, George Balanchine, Jorma Elo, Xing Liang and Edwaard Liang. The SDT is also closely affiliated with the work of the late virtuoso Singaporean choreographer Goh Choo San. Goh, who was the brother of Goh Soo Khim, was the choreographer for the Washington Ballet in the 1980s.

In 2008, Janek Schergen was appointed artistic director of the SDT, taking over from Goh Soo Khim, who stepped down after 20 years at the helm. Janek, who was previously the dance company’s assistant artistic director, also oversees the Choo-San Goh & H. Robert Magee Foundation, which licenses and produces Goh Choo San’s ballets as well as administers the annual Choo-San Goh Awards for Choreography.

A number of notable dancers and choreographers in the Singapore dance scene have passed through the hallowed halls of the SDT, including choreographer Jeffrey Tan and dancer Kuik Swee Boon.

While the SDT is primarily a classical ballet company, it has taken on a few landmark contemporary productions, such as Reminiscing the Moon (2002) by Indonesian choreographer Boi Sakti for the inauguration of Esplanade –Theatres on the Bay. One of its most popular events is Ballet Under the Stars, an annual outdoor ballet performance that takes place at Fort Canning Park and draws large crowds every year.

In 2013, the SDT moved to bigger premises at the Bugis+ shopping mall on Victoria Street, after more than 20 years at the Fort Canning Centre.

Artistic Director Janek Schergen of the SDT teaching a class. Courtesy of Singapore Dance Theatre.

Artistic Director Janek Schergen of the SDT teaching a class. Courtesy of Singapore Dance Theatre.

Finding Voice Through Art

Balancing tradition and modernity, Eastern and Western styles, the Singaporean dancer often treads between worlds. From the modern dance styles of Lim Fei Shen, to the experimental site-specific performances of Arts Fission Dance Company, to the contemporary dance styles of ECNAD and Frontier Danceland, dance in Singapore takes shape in many forms – but they all come together to form an inkling of the socio-cultural tensions that exist in our multicultural island-nation.

As a relatively young country, with a relatively young arts scene, the artistic voices of our dance pioneers are surprisingly strong and diverse. Be it the classical ballet repertoire of the SDT or the light-footed movements of Santha Bhaskar’s take on Bharatanatyam dance, these dance pioneers collectively paint a complex and intriguing picture of post-colonial identity in contemporary Singapore.

For what is art but a lens through which to examine society, and in turn, ourselves? Artists speak of the cultural inflections that influence their works, that weave paths through classical arts, gestures and rituals, that stir the desire for a truer, more unique expression of identity that Singapore can truly call its own. Singapore’s history, from its time as a British trading port under colonial rule to a first-world metropolis, presents us in an unusual, liminal space. Perhaps there lies the meaning of evolving tradition to reflect relevance in modern times. To understand who we are, we should perhaps turn to the most primitive of communication – the body – to decipher and find meaning in the gestures, signs and signifiers created by the Singaporean dancer.

Tara Tan is a writer and designer who works in the intersection between art, design and technology. She was a former arts reporter with The Straits Times, where she wrote on dance and culture in Singapore.

NOTES

-

An interview with Santha Baskar from the film “Mrs Santha Bhaskar”. (2010) by Tara Tan. ↩

-

Tan, T. (2011, May 23). Moving ode to loss. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Goh, C.L. (2014, May 3). The ballerina who overturned tables. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 3 May 2014, p. 4. ↩

-

Purushothaman, V. (Ed.). (2002). Narratives: Notes on a cultural journey: Cultural medallion recipients 1979–2001 (p. 32). Singapore: National Arts Council. (Call no.: RSING 700.95957 NAR) ↩

-

Mrs Santha Baskar, 2010. ↩

-

Mrs Santha Bhaskar, 2010. ↩

-

Mrs Santha Bhaskar, 2010. ↩

-

Lee, V. (2015, February 23). Traditional innovator. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Feb 2015, p. 4. ↩