Finding Magic Everywhere

According to Farish A. Noor, many of the beliefs and rituals described in Walter Skeat’s book Malay Magic may not be considered particularly “magical”.

A Malay pawang of the Straits Settlements, c. 1900. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Malay pawang of the Straits Settlements, c. 1900. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Originally published in 1900, Walter William Skeat’s Malay Magic was conceived as a comprehensive description of Malay beliefs, folklore and customs. Among other things, it covers customs and rites relating to various aspects of the natural world.

For example, Skeat writes about how Malay pawang (shamans) detect perfumed agarwood (also known as eaglewood), or locally, gaharu.1 The perfume is created by a disease that infects the inner heartwood of the aquilaria tree, making it impossible to tell if a tree is valuable from the outside, hence the need for a pawang. According to Skeat, the process involves the pawang burning incense and repeating a charm or formula until the right tree is found.

Skeat’s work was considered groundbreaking but some scholars have critiqued the work for positioning Malay knowledge and practices as “charms” and “rituals”, where in many cases they were simply traditions through which practical experience and scientific information were passed on.

The title page of Malay Magic by Walter William Skeat. Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 SKE; Accession no.: B02930611K).

The title page of Malay Magic by Walter William Skeat. Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 SKE; Accession no.: B02930611K).

During the colonial era, data-collecting and knowledge-building went hand-in-hand with conquest and territorial expansion. This was as true of the British Empire as it was with the other European powers – like the French, Dutch and Portuguese – who expanded their spheres of influence across Southeast Asia.

In tracing the development of colonial knowledge during the age of Empire, Thomas Richards noted that “the British may not have created the longest-lived empire in history, but it was certainly one of the most data-intensive”.2

Empires were built not only by force of arms, but also by colonial scholars and data-collectors who brought with them a host of preconceived culturally specific notions about the Asian Other. Consequently, their works tended to portray non-Western societies as different, alien and strange.

One such scholar was Walter William Skeat, an anthropologist of the Malay Peninsula whose detailed works laid the foundation for later ethnographic studies of the region. His studies on Malay culture, language and belief systems were, at the time, regarded as being among the most comprehensive and thorough ever produced.

While not denying the near-exhaustive scope of Skeat’s work, my view is that colonial knowledge production was rarely a truly consultative process that engaged different knowledge systems in a dialogue of equals. Instead, it was an unequal process where non-Western belief systems and knowledge systems were often deliberately downplayed and shunned; these tended to be perceived as antiquated myths, outdated folklore and even arcane “magic”. We can see this in the work of Skeat and his collaborator, Charles Otto Blagden.

Malay Magic as a Form of Colonial Knowledge-Power and Othering

Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula3 marked the beginning of Skeat’s partnership with Blagden, an English Orientalist and linguist known for his expertise in Southeast Asian languages – notably Malay and the Mon language of Burma (now Myanmar). Blagden wrote the preface and also saw the book through the final stages of its publication.

Malay Magic was the result of the fieldwork that Skeat had undertaken in the Malay interior, notably in the kingdom of Selangor and the areas bordering the kingdoms of Pahang and Perak. Skeat and Blagden would later collaborate while studying the aboriginal peoples of the Malay Peninsula, and the outcome of their joint research is the co-authored work, Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula, published in 1906.4

Malay Magic by Walter William Skeat. This edition was published by Silverfish Books in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018.

Malay Magic by Walter William Skeat. This edition was published by Silverfish Books in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018.

Skeat begins Malay Magic with a quotation from Rudyard Kipling’s The White Man’s Burden, which sets the tone for the rest of his inquiry:

“The cry of hosts (we) humour

Ah! Slowly, toward the light.”5

Thus from the outset, the dialectical pairing of light and darkness is introduced, bringing with it the values and the trains of thought derived from a Western Enlightenment project that would come barrelling down upon the body of Malay beliefs, customs and knowledge.

In his preface to Malay Magic, Blagden noted that Skeat’s aim was to collect into a book of Malay folklore “all that seemed to him most typical of the subject amongst a considerable mass of materials, some of which lay scattered in the pages of other works, others in unpublished native manuscripts, and much in notes made by him personally”.6 To that end, Skeat had consulted all “the principle authorities” on the subject. These experts on things Malay and Malayan – who included Straits Settlements Colonial Secretary William Edward Maxwell (1892–95), as well as colonial administrators Frank Athelstane Swettenham and Hugh Charles Clifford, both of whom later became governers of the Straits Settlements – all happened to be Englishmen.7

Skeat provided the list of works that he had consulted at the end of the book, where Orientalist and numismatist William Marsden, linguist and poet John Leyden and second Resident of Singapore John Crawfurd (1823–26) – all employees of the British East India Company – were also cited as his main sources of information.8

Skeat and Blagden were particularly interested in the beliefs and customs of the Malays in particular as their research was conducted within the domain of what was then British Malaya. The beliefs of other non-Malay communities (notably Chinese migrants) were deemed of secondary importance.9

Dissecting Malay Magic

The organisation of Malay Magic is systematic, beginning with an account of Malay beliefs about the creation of the world and natural phenomena, followed by the place of Man in the universe. From the third chapter onwards, Skeat devotes most of his attention to the Malay magician or shaman (pawang) and his relationship with the supernatural world before moving on to the Malay pantheon, the rites and rituals of Malay life in relation to the natural world, and magic rites affecting the life of Man.

At times, however, just where the boundary between the natural and supernatural lies is somewhat unclear in Skeat’s account. Many of the taboos and restrictions (including sartorial norms and rules of language use) that he talks about had less to do with magic or matters arcane, and more to do with social conventions and modes of identity construction in Malay society.10

Quite early on in the text, the reader can see how Skeat’s attempt at universalising Malay beliefs and customs is one that compares Malay beliefs and cultural praxis with other non-Western cultures deemed primitive and less civilised to Europeans. For instance, when he points out that in Malay society, the head of a person is considered the most important part of the body, and that patting a person on the head is regarded as insulting, his immediate point of comparison was the communities of Polynesia.11 One might ask, though, whether an ordinary Englishman at the time would be happy to be patted on the head by complete strangers for no apparent reason.

Skeat framed the object of his inquiry (the Malay and his beliefs) in the category of the unscientific, irrational and superstitious. It is against that backdrop of native primitivism that Skeat introduces the figure of the Malay magician, who “is a functionary of great and traditional importance in a Malay village, though in places near towns the office is falling into abeyance”.12 In this description, he introduces a second binary, which is that of the rural-urban divide. Although Skeat recognised that the pawang occupied a position in society that placed him at an equally high standing with members of the aristocracy and royalty,13 he nonetheless located the magician in a domain of its own, associated with all things supernatural and esoteric.

By the time we reach the second half of Skeat’s near-exhaustive study of Malay customs and practices, we encounter his detailed descriptions of Malay cultural activities and pastimes, such as children’s games and nursery rhymes, card games, board games – including chess, of all things – and buffalo fights and cockfighting. That cockfighting made its way into his study of Malay magic says something about how Skeat was perhaps over-extending himself. Nursery rhymes, card games and cockfighting may have been part of the Malay cultural praxis in general, but if cockfighting was indeed a form of magical activity, then one can only conclude that there was a lot of magic going on at the dockside pubs of London too.

From here, it does not require much effort for the present-day reader to see that in Skeat’s data-gathering, a lot of object-framing was going on as well. Because Skeat had laid as his foundational premise the notion that the Southeast Asian mind was one that was fundamentally unscientific, it followed that anything and everything the Malays did was suffused with the elements of the magical, esoteric and mysterious.

Skeat’s propensity to find magic wherever he looked is perhaps most evident in the section of his work where he discusses the role of the pawang of the tin mines. In chapter five, Skeat devotes an entire section on minerals in the natural world and mining charms. It is here that he writes about the “mining wizard”, an individual of considerable importance in the mining districts of Perak and Selangor.14

Tin mining in Ipoh, Perak, c. 1910. In chapter five of Malay Magic, Walter William Skeat discusses the role of the “mining wizard” or pawang, an important individual in the mining districts of Perak and Selangor. Retrieved from Southeast Asian & Caribbean Images (KITLV), Leiden University Libraries (CC BY 4.0).

Tin mining in Ipoh, Perak, c. 1910. In chapter five of Malay Magic, Walter William Skeat discusses the role of the “mining wizard” or pawang, an important individual in the mining districts of Perak and Selangor. Retrieved from Southeast Asian & Caribbean Images (KITLV), Leiden University Libraries (CC BY 4.0).

Yet upon closer reading, it seems that the role of the famous “mining wizard” in the tin-mining districts was closer to that of a factory foreman, whose duty was “to carry out certain ceremonies, for which he is entitled to collect the customary fees, and enforcing certain rules for the breach of which he levies the customary fines”.15 The rules (or taboos/pantang) enforced by the pawang of the mines are listed by Skeat as follows (paraphrased), with the fines or penalties enclosed in brackets:16

- No bringing cotton or raw cotton to the mines ($12.50);

- No wearing of black coats/shirts ($12.50);

- No using of earthenware or clay gourds for carrying water ($12.50);

- No gambling anywhere in or near the mines ($12.50);

- The building of aqueducts is to be done away from the mines ($12.50);

- No using of the bahasa pantang (forbidden language) of the pawang ($12.50);

- No smearing charcoal on the faces of miners ($12.50);

- No wearing of the clothes of other miners (one karong [sack] of tin sand);

- A broken chupak (measure) of the mine should be replaced or repaired within three days (one bhara of tin);

- No bringing of weapons of any kind to the mine or the smelting-house ($1.25);

- No wearing of coats at the smelting-house ($1.25);

- No cutting or slashing of any posts in the mine or smelting-house (one slab of tin);

- No stealing rice or eating rice without the consent of the owner (one karong of tin sand);

- All earthenware pots are to be replaced within three days (one karong of sand);

- No miner should be sluicing for tin upstream above another miner who is already working there (tin sand payable to the latter);

- Any keris (dagger) or spear that is without a sheath of its own must be covered and hidden from view (“amount uncertain”); and

- The obligatory payment to the pawang of the sum of one chupak of tin sand upon the death of any miner.

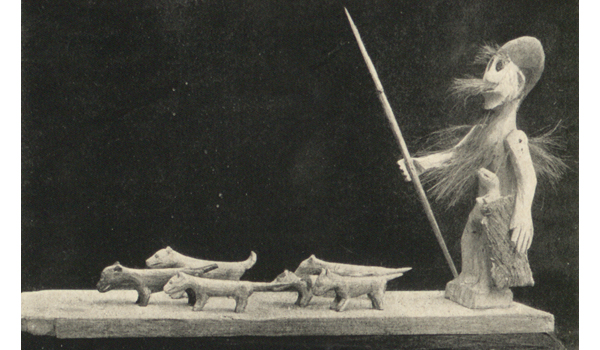

The Spectre Huntsman (hantu pemburu) roams the forest carrying a spear in his right hand and with his dogs in search of a quarry. Its appearance is the harbinger of disease or death. Image reproduced from Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula (after p. 116). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 SKE; Accession no.: B02930611K).

The Spectre Huntsman (hantu pemburu) roams the forest carrying a spear in his right hand and with his dogs in search of a quarry. Its appearance is the harbinger of disease or death. Image reproduced from Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula (after p. 116). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 SKE; Accession no.: B02930611K).

Just exactly how most of these rules could count as “magical” is difficult to see as they seem to be more practical in nature. From the mid-19th century onwards, the tin-mining districts of Perak and Selangor were opened up even further and by the time Skeat was writing his book, the previously dominant position of Malay entrepreneurs, such as the Dato Panglima Kinta (Lord of Kinta) of Kinta Valley in Perak, had been usurped by the advances of British and other Western capital as well as the influx of migrant workers brought in by the British.

The tin mines of Perak and Selangor were male-dominated spaces that were full of poor and underpaid miners who were either local Malays or Chinese migrants. Being spaces of evident economic and power differentials (between the mine owners and the mine workers), and whose conditions were at the same time hot, damp, dusty and unsanitary, workers were vulnerable to bouts of malaria, beri-beri and other diseases. Such places were potential tinderboxes.

Under such circumstances, most of the rules of the so-called “mining wizard” make sense to us today as they presumably did then as well: the prohibition of gambling and bearing weapons, and the stealing of rice and clothes, etc., were all intended to foreclose the possibility of theft, fighting and murder among the miners. Likewise, the prohibition of wanton destruction of property (such as the slashing of posts) and the wearing of coats in the smelting-house (where the burning furnace would be active) seems a perfectly logical way of preventing workplace accidents and the unnecessary loss of human life among the underpaid miners.

Given the commonsensical nature of the “mining wizard’s” restrictions and rules, Skeat does not concede the possibility that these regulations were not so different from the health and safety regulations enforced at coalmines back in England, or the rules on board a vessel of the Royal Navy.

The closest we get to a more mundane account of the life and work of the pawang of the tin mines is when Skeat writes about the political economy of the mining industry in colonial Malaya at the time, and how the pawang was in the enviable position of being able to exploit his rank and status in the face of foreign capital.17 Yet at no point in his narrative does Skeat acknowledge the fact that the territory of Perak had been a contested one during the Perak War (1875–76), which extended British political influence over the Malay Peninsula.

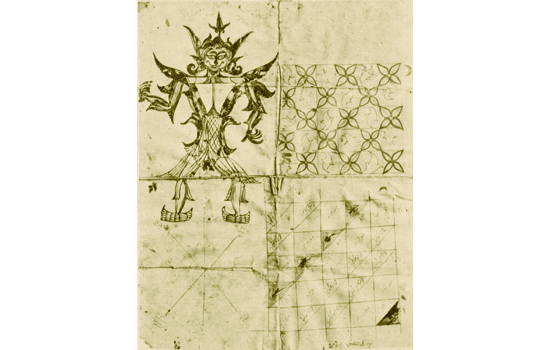

An illustration from Malay Magic which shows diagrams used by pawang for divination. The top left figure has different points drawn on its anatomy for divination means. The bottom left diagram is used like a compass with the diviner counting around it from point to point. The diagrams on the right are two different types of “magic squares”. Image reproduced from Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula (after p. 554). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 SKE; Accession no.: B02930611K).

An illustration from Malay Magic which shows diagrams used by pawang for divination. The top left figure has different points drawn on its anatomy for divination means. The bottom left diagram is used like a compass with the diviner counting around it from point to point. The diagrams on the right are two different types of “magic squares”. Image reproduced from Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula (after p. 554). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 SKE; Accession no.: B02930611K).

Back in England, proponents of further British capital penetration – aided and abetted by a bellicose British press that was clamoring for the annexation of Perak – had been baying for greater control over the tin deposits. Nor does Skeat acknowledge that the Malays knew the lay of their land better than foreigners, and that some Malays knew where tin deposits could be found thanks to their understanding of their own geography.

Magic and Primitivism in the British Empire

Primitivism tends to be sticky, and it can remain in the minds of those who believe in it and then find it wherever they look. Skeat wasn’t the first, or the only Westerner to become fixated by the view that the people of the Malay Peninsula were the bearers and reproducers of some form of Asiatic essentialism: such ideas had been in circulation since the 18th century, thanks to the work of men like William Marsden, Stamford Raffles and John Crawfurd.

These notions would eventually become sedimented and entrenched in the writings of subsequent British colonial scholar-functionaries stationed in British Malaya, such as historian Oliver William Wolters, Frank Athelstane Swettenham and Richard Olaf Winstedt. These ideas also had consequences on the ground. It was Winstedt who – as Assistant Director of Colonial Education in the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States – would introduce the so-called “rural bias” to the colonial education system on the grounds that the Malays would be better served if they were taught vocational courses in farming and animal husbandry rather than science and history.

Although Skeat and his fellow scholars were living and working in a Malaya that had been by then seemingly “domesticated” and “civilised” by colonial rule, it is important to remember that behind that history of pacification and domestication was also a history of violence and subjugation. That none of these men cared to speak or write about the historical circumstances that brought the British Empire to the doorsteps of the Malay Archipelago is a glaring omission that points to the myopia evident in their scholarly works. These men were not in Malaya by chance: all of them were functionaries in a colonial administrative system that locates them firmly in the centre of the machinery of the Empire.

Skeat’s work was indeed vast and near-exhaustive, but the problem does not lie in the scope of his scholarly ambitions, but rather in the lens which was brought to bear upon the objects of his study. Simply put, if one were to approach something by seeing it as a problem right from the outset, one will undoubtedly encounter problems wherever one looks.

The same can be said of Skeat’s quest for traces of the magical, arcane and supernatural in his study of Malay society. Persuaded by his own view that the Malays (and other Southeast Asians) were an agrarian people whom he perceived as historically behind the nations of Western Europe, Skeat uncovered traces of magic in almost everything he looked at. But we cannot dismiss the very real possibility that what Skeat saw and understood as “magical” in the Malay world was in fact mundane and ordinary to the Malays themselves.

Skeat’s work is less interesting for the things he says about the Malays but more interesting for the things he does not say about himself. That such authors – who were surely aware of their own respective subject-positions in the colonial order of knowledge and power – were seemingly unaware of their role in the endless reproduction of native stereotypes speaks volumes about the workings of the Empire’s echo-chamber.18

Dr Farish A. Noor is Associate Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His recent works include Racial Difference and the Colonial Wars of 19th Century Southeast Asia (edited with Peter Carey, 2021), and Data Collecting in Colonial Southeast Asia 1800–1900: Framing the Other (2020).

Dr Farish A. Noor is Associate Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His recent works include Racial Difference and the Colonial Wars of 19th Century Southeast Asia (edited with Peter Carey, 2021), and Data Collecting in Colonial Southeast Asia 1800–1900: Framing the Other (2020).

NOTES

-

Agarwood is the dark resinous heartwood of the aquilaria tree. It is formed when the aquilaria tree becomes infected with a type of mould. Prior to infection, the heartwood is odourless, relatively light and pale coloured. As the infection worsens, the tree produces a dark aromatic resin called aloes or agar. Agarwood is used as a raw material for incense, perfume and medicine. ↩

-

Thomas, R. (1993). The imperial archive: Knowledge and the fantasy of empire (p. 4). London: Verso Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay magic: Being an introduction to the folklore and popular religion of the Malay Peninsula. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 SKE; Accession no.: B02930611K) ↩

-

Skeat, W.W., & Blagden, C.O. (1906). Pagan races of the Malay Peninsula. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 301.209595 SKE) ↩

-

On page 675 of Malay Magic, Skeat lists the “chief authorities” quoted in his work, and perhaps not surprisingly – with the exception of Klinkert’s and Wall’s Malay dictionaries – they were all the works of fellow Englishmen. ↩

-

There are few instances where Skeat writes about the interaction between the Malays and Chinese in colonial Malaya then, and it becomes evident early on that the belief systems of the Chinese were of lesser concern to him. When discussing the topic of Malay shrines (keramat), he noted that “I have never yet, however, heard of any shrine dedicated to a Chinaman, and it is probably that this species of canonisation is confined (at least in modern times) to local celebrities professing the Muhammadan religion, as would certainly be the case of the Malays and Javanese mentioned. […] It is true that Chinese often worship at these shrines – just as, on the same principle, they employ Malay magicians in prospecting for tin; but there appear to be certain limits beyond which they cannot go”. See Skeat, 1900, pp. 69–70. ↩

-

Skeat, 1900, p. 43. It is also interesting to note that Skeat’s comparison of the Malays with Polynesians came from James George Frazer. See Frazer, J.G. (1890). The golden bough: A study in magic and religion (vol. I, p. 189). London: Macmillan. [Note: NLB has the third edition in 12 volumes. See Frazer, J.G. (1911–1915). The golden bough: A study in magic and religion. London: Macmillan. (Call no.: RCLOS 291 FRA-[RFL])] ↩

-

Skeat, 1900, pp. 56–57, quoting Hugh Clifford. See Clifford, H.C. (1897). In court & kampong: Being tales and sketches of native life in the Malay Peninsula (p. 28). London: G. Richard. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 915.95 CLI; Accession no.: B02806362E) ↩

-

Farish A. Noor. (2016). The discursive construction of Southeast Asia in 19th century colonial-capitalist discourse. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.0072 FAR); Farish A. Noor. (2019, April). Mea culpa: Re-reading nineteenth century colonial-era works on South East Asia as confessional texts. Southeast Asia Research: The Past, Present and Future of Area Studies, 27 (1), 74–96. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online; Farish A. Noor. (2020). Data-gathering in colonial Southeast Asia 1800–1900: Framing the other. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. (Call no.: RSING 325.59 FAR) ↩