A Banquet of Malayan Fruits: Botanical Art in the Melaka Straits

Who commissioned the Dumbarton Oaks collection of 70 drawings on local fruits? Faris Joraimi attempts to unravel the mystery of its origins, which could predate Raffles’ arrival.

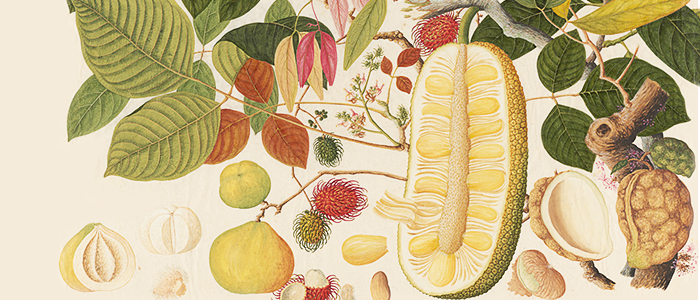

In this set of drawings from the Dumbarton Folio featuring mangosteens, there are unopened flower buds, flowers in full bloom, juvenile fruits as well as fully ripe ones, all on the same branch. The other three types of fruit are the ivory yellow rambutan, jambu air and buah melaka. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

In this set of drawings from the Dumbarton Folio featuring mangosteens, there are unopened flower buds, flowers in full bloom, juvenile fruits as well as fully ripe ones, all on the same branch. The other three types of fruit are the ivory yellow rambutan, jambu air and buah melaka. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

The expansion of European imperial power in the Malay Archipelago beginning in the early 19th century introduced not just conscripted soldiers, missionaries and colonial officials, but also explorers and naturalists. Their urge to catalogue and classify generated an extensive visual record of flora and fauna found in Southeast Asia.

Painters – although not often associated with the branches of science – were instrumental to the study of natural history. The William Farquhar Collection of Natural History drawings,1 for instance, enjoys the privilege of being Singapore’s best known and most publicly accessible set of botanical art from the early colonial period. The 477 watercolour paintings of plants and animals from Singapore and Melaka by unnamed Chinese artists (most likely Cantonese) were commissioned by Farquhar between 1819 and 1823 when he was First Resident and Commandant of Singapore. The entire collection currently resides in the National Museum of Singapore.

The Dumbarton Oaks Collection

This story, however, is about a far more modest, and relatively obscure, collection: one folio of 70 drawings, but no less intriguing because of its mysterious origins and almost singular uniqueness. In locating this folio, our scene shifts an ocean away, to the United States.

In 2019, I visited the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, a historic estate about the size of 20 football fields. Nestled in Georgetown, a manicured district in Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks comprises a mansion surrounded by lush gardens. The estate made history in 1944 when international delegates convened here for a series of critical meetings that led to the creation of the United Nations. It was also the residence of Robert and Mildred Bliss, influential and wealthy cultural patrons who were active in politics and philanthropy. Today, Dumbarton Oaks is a research institute where Mildred Bliss’ vast collection of Byzantine and Pre-Columbian art keeps company with valuable manuscripts on gardens and landscaping.

Carefully housed among the shelves in its impressive reading room is this folio containing exquisite depictions of fruits from the Malay world. The bound volume has no label on its cover save a generic title, “Chinese Watercolours: Fruits”, hot-stamped in gold on the spine. The drawings feature 57 species of fruits commonly found in Southeast Asia, such as pineapples, watermelons, mangosteens and durians.

Scientific Illustration as an Aesthetic

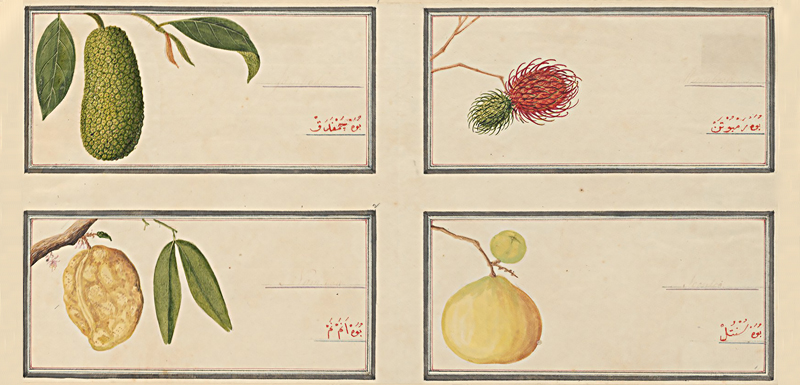

The Dumbarton Folio is structured in three parts. The first 12 watercolours are composite scenes, each showcasing four species of fruit. Following these are 10 drawings, each focused on a specimen of a single species. In the last section, each page depicts eight fruits drawn in miniature, two groups of four. Each group – two rows on top and two rows below – corresponds to the four species depicted in each of the 12 composite scenes. The groups of four are arranged in the order of the corresponding composite scenes, and each fruit is labelled according to its Malay name in Jawi as well as poor transliterations in barely visible Roman script.

Each page in the last section of the Dumbarton Folio depicts eight fruits drawn in miniature, two groups of four. Each group – two rows on top and two rows below – corresponds to the four species depicted in each of the 12 composite scenes. Each fruit is labelled according to its Malay name in Jawi as well as poor transliterations in barely visible Roman script. Shown here are the top two rows from one of the pages. Clockwise from the top: cempedak, red rambutan, sentul and nam-nam. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Each page in the last section of the Dumbarton Folio depicts eight fruits drawn in miniature, two groups of four. Each group – two rows on top and two rows below – corresponds to the four species depicted in each of the 12 composite scenes. Each fruit is labelled according to its Malay name in Jawi as well as poor transliterations in barely visible Roman script. Shown here are the top two rows from one of the pages. Clockwise from the top: cempedak, red rambutan, sentul and nam-nam. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

The folio dissolves hard distinctions between conventionally “scientific” documentation and “ornamental” representation. Of course, the key formal features of botanical illustration are strongly evident. For instance, the fruits are typically drawn on plain backgrounds which traditionally serve to isolate the specimen from its original setting, so that it could be properly recorded and observed. This was a near-universal procedure used by European botanists for representing specimens collected in the field.2 Another typical element is the portrayal of multiple stages in the plant’s life cycle within a single drawn specimen. In the set of drawings featuring mangosteens for example, the viewer is shown unopened flower buds, flowers in full bloom, juvenile fruits as well as fully ripe ones, all on the same branch.

Historian Daniela Bleichmar, who studied 16th-century botanical drawings by colonial Spanish expeditions to the Americas and the Philippines, found these features to be among the “iconographic strategies” that allowed artists to “compress time and space” in order for drawings to contain the necessary botanical information.3 While plants in reality take time to manifest visible changes across different seasons, an artist could capture the full range of that information on one page. In a “single imaginary specimen”, for instance, the plants could be rendered in different stages of growth to depict all possible conditions it could be in.4 The botanical illustration was effective at capturing knowledge obtained about the biodiversity of distant colonies for circulation and analysis in the imperial centre. This involved a degree of artistic manipulation, however, distorting essential distinctions we have about “objective” versus “artistic” representation.

Viewing these drawings, one also cannot help but notice how intensely lyrical the compositions are. Highly expressive, the scenes are richly illustrated with leaves and stems entwined around one another. Vividly textured fruits catch one’s eye among the foliage. In most of these pieces, the leaves and branches are cut off at the edges of the frame. A visual protagonist dominates each scene, usually a fruit like a cempedak, mangosteen or durian.

A notable example features a large pineapple, whose seductive shade of pink is characteristic of the species, Ananas bracteatus (red pineapple). It is a different variety from Ananas comosus, which we find in every local wet market and supermarket. Ananas bracteatus, on the other hand, is esteemed for its pretty foliage: note the stripes and red-tinted edges. The artist evidently decided to show off these ornamental qualities by having one of the leaves drape elegantly across the page.

Included in the Dumbarton Folio is the composite drawing featuring the Ananas bracteatus (red pineapple), with its distinctive shade of pink skin characteristic of the species, and the langsat, chiku and kundang. Although the exterior of the pineapple is pink, it has a fleshy yellow pulp like other pineapple varieties. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Included in the Dumbarton Folio is the composite drawing featuring the Ananas bracteatus (red pineapple), with its distinctive shade of pink skin characteristic of the species, and the langsat, chiku and kundang. Although the exterior of the pineapple is pink, it has a fleshy yellow pulp like other pineapple varieties. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

We find instances of lyrical expressions in the second set as well. The stunning watermelon painting depicts swirling tendrils with leaves and flowers shown in distinct stages of development. Like the pineapple, the watermelon is also cut in half to reveal its fleshy red interior, with the seeds laid aside. All the fruits in both the composite scenes and single-species studies are dissected this way. Revealing the anatomy of the fruit, down to every last succulent pulp, pit and seed, was crucial to botany’s thorough investigation of plant life. Dissection was an invaluable technical skill. Many pioneering botanists, such as Nathaniel Wallich,5 were surgeon-naturalists after all.

Little is known about the precise circumstances surrounding the volume’s production, or who and what it was intended for. There is no information that survives regarding how and why it came into the custody of the Blisses. However, it likely predates the William Farquhar collection, and indeed the establishment of a British trading post in Singapore in 1819. The late Mildred Archer, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the India Office Library in London, dated the Dumbarton Folio’s production to be roughly between 1798 and 1810.6 To the best of my knowledge, it is the only such volume known to exist, and there are no known duplicates. Only two of its illustrations find parallels in one other collection. Apart from those, every other painting is unique.

The title given on the spine is, at least, accurate. Like the Farquhar drawings, those in the Dumbarton Folio bear the stylistic mark of Chinese artists trained in the Cantonese tradition of ink painting in the ateliers of southern Chinese ports. For instance, the light blue shade applied as a backdrop to white-coloured flowers was a signature technique in Chinese watercolour painting.

Generally, British officials working in Southeast Asia in the 19th century commissioned Chinese artists to produce botanical illustrations. Abdullah Abdul Kadir (more popularly known as Munshi Abdullah), who was employed by Stamford Raffles as his scribe and interpreter, corroborates this fact in his memoir, Hikayat Abdullah (The Tale of Abdullah): Stamford Raffles himself employed painters from Fujian and Macau while playing gentleman-naturalist in the forests of Singapore.7

What also stands out about the folio was its inclusion, in clear hand, of the Malay names for all the 57 fruits depicted. The Jawi script reads as sharply today as perhaps when it was first inscribed. Who identified these names? Was there a local expert consulted? Maybe – as with the William Farquhar Collection – the British official who commissioned these drawings had instructed artists to visit the local marketplace: all the fruits depicted are edible after all; in which case, all it took was to ask the fruit seller what they were called.

But who wrote the names? Before mass education, most people in the Malay world were illiterate. “Penmanship”, noted Amin Sweeney and Nigel Phillips, “was an exclusive art”.8 Literature flourished almost only within palace walls. Still, there lived in the European entrepots like Melaka and Batavia (present-day Jakarta) a handful of professional Malay scribes who served as secretaries and polyglot interpreters for merchants and diplomats: Munshi Abdullah and his father, for instance. Someone of such standing and occupation could have been the ghostwriter. It is almost certain that a folio like this could have only been produced in one of the few Malay-speaking, European-controlled ports along the Straits: Melaka and Penang on the Malay Peninsula, or Bencoolen (now Bengkulu) in Sumatra. The William Farquhar Collection also has Jawi labels, but like the anonymous Chinese artists who did the illustrations, the identity of the author of the labels remains elusive.

Following the Watermelon’s Lead

There are only two pieces in the entire Dumbarton Folio that find almost exact matches in another collection of botanical art. A few months after encountering Dumbarton’s Malay fruits, I chanced upon the watermelon’s twin in Mildred Archer’s catalogue, British Drawings in the India Office Library.9 It was listed as being part of a folio simply titled NHD 42, housed at the Prints and Drawings Room of the British Library. Leafing through the large sheets of drawings in the Asian and African Prints Room of the British Library, I discovered a pomelo study among the 10 watercolours in NHD 42 that was also an almost exact twin of the one in the Dumbarton Folio.

The watermelon painting in the Dumbarton Folio (left) depicts swirling tendrils with leaves and flowers shown in distinct stages of development. The watermelon is also cut in half to reveal its fleshy red interior and black seeds. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. An almost exact replica of the painting (right) can be found in the bound folio titled NHD 42 housed at the Prints and Drawings Room of the British Library. Photo by Faris Joraimi.

The watermelon painting in the Dumbarton Folio (left) depicts swirling tendrils with leaves and flowers shown in distinct stages of development. The watermelon is also cut in half to reveal its fleshy red interior and black seeds. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. An almost exact replica of the painting (right) can be found in the bound folio titled NHD 42 housed at the Prints and Drawings Room of the British Library. Photo by Faris Joraimi.

Unfortunately, the British Library has no idea who NHD 42 was made for and why, but at least they have firmer dates: the watermark on the sheets of paper used for the drawings is from 1807, so the NHD 42 most likely dates back to 1808. This places it comfortably within Archer’s 1798–1810 range for the Dumbarton Folio. The artist is also a Chinese “probably from Sumatra”, and the drawings “appear to have been borrowed by the Marsdens in 1809.”10

There can only be one pair of “Marsdens” where Sumatra is concerned: William Marsden and his wife Elizabeth. The former’s landmark book, The History of Sumatra, published in 1783, was a magisterial survey of the island, with observations on its cultures, languages and physical environment.11 An Orientalist, William’s work became the model for Stamford Raffles’ more intellectually and morally impoverished The History of Java (1817).12

Elizabeth contributed the illustrations to her husband’s tome. At some point, Charles Wilkins, her father and himself a leading Indologist, was in possession of NHD 42, and lent it to Elizabeth who adapted some of the drawings for her husband’s book.13 Beyond this, nothing more about this folio is known. Despite the Bencoolen connection, we still do not know where NHD 42 was produced; it found its way to the Marsdens only in England. Therefore, it offers no satisfying clue as to where the Dumbarton Folio was made either.

Nevertheless, the duplicates led me to briefly entertain the possibility of model types, circulated to enable the reproduction of copies produced for a wide clientele expecting the same images. If, however, such an established commercial market existed, with demand sufficient to justify some sort of mass production, we will have likely found many more duplicates and not a mere two drawings. It is far likelier that these duplicates were individually copied.

A composite drawing from the Dumbarton Folio featuring the durian, pulasan, rambai and rukam. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

A composite drawing from the Dumbarton Folio featuring the durian, pulasan, rambai and rukam. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

For the sake of comparison, shown here is the durian from the William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

For the sake of comparison, shown here is the durian from the William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

What is the Dumbarton Folio, then? Its scale and scope do not match that of earlier, more encyclopedic catalogues documenting local ecology in the Malay world. A century earlier, there was Johannes Nieuhof’s Voyages and Travels, into Brasil, and the East Indies, for instance, with its elaborate accounts of this region’s flora and fauna, published in 1703.14 Neither does the folio engage in the kind of intense accumulation of data found in Georg Eberhard Rumphius’ six-volume Het Amboinsche Kruidboek, or Herbarium Amboinense, a catalogue of the plants of the island of Ambon, published posthumously from 1741 to 1750.15 By the time the Dumbarton Folio was produced, the field of botany had been established in the region. And while it was likely made slightly before the Farquhar drawings, it falls far short of the latter’s range, but its style is certainly more ornate.

The academic Farish Noor believes that the folio was commissioned as a picturesque record of local flora by a European official, most probably someone from the British East India Company (EIC), who wanted a souvenir to take home.16 A lovely present, surely, for a wife none too pleased that her husband’s little excursion to the “Far East” had lasted several more years than promised. This was exceedingly common in the 18th and 19th centuries, especially in India, where EIC officials hired local painters to depict ancient monuments, people and, of course, “exotic” plants and animals to be taken home as mementos.17 Many of these artisans were trained in the courtly tradition of Indian miniature painting, but to suit the European aesthetic preferred by their British patrons, they developed a hybrid Indo-European type of painting now referred to as “Company style” or “Company painting”.

When the EIC officials were posted to Southeast Asia, the Indian artists apparently did not accompany their British employers. However, the EIC officials found a ready pool of Chinese artists steeped in their own tradition of ink painting. Historian Kwa Chong Guan referred to the Farquhar drawings as a “charming and distinct record” of Chinese artists grappling with European demands for realism.18 Commentators looking at similar collections from the period have christened them collectively as the “Straits school” of botanical art.19 The Dumbarton Folio is without doubt a product of this tradition.

While drawing upon the representational conventions of botanical illustration, the Dumbarton Folio was not intended as a formal catalogue of nature the same way the Farquhar collection was. What the folio does, however, is demonstrate the deployment of these conventions as an aesthetic in its own right, to be enjoyed as art. Looking at these drawings, my thoughts floated to the Nanyang Style artists20 and their delicate still lifes in the 1950s: the rambutans, durians and mangosteens of Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi and Georgette Chen.21 By then, painting local fruits was about capturing the “soul” of Malaya in all its living colour. These Nanyang artists certainly had illustrious predecessors.

A composite drawing of the cempedak, rambutan, nam-nam and sentul from the Dumbarton Folio. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

A composite drawing of the cempedak, rambutan, nam-nam and sentul from the Dumbarton Folio. Image reproduced from Album of Chinese Watercolours of Asian Fruits, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

The Scientific Cosmopolitanism of the Malay World

When the Dumbarton Folio was made, Europeans still had much to learn about the biodiversity of the Malay Archipelago. It would take the exertions of later naturalists, notably Alfred Russel Wallace (who conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection), Henry Nicholas Ridley (first director of Singapore’s Botanic Gardens), Pieter Bleeker (Dutch medical doctor, ichthyologist and herpetologist) and Isaac Henry Burkill (second director of Singapore’s Botanic Gardens), to identify and describe the grand multitude of life in the region. Their illustrated catalogues and scientific encyclopedias brought these strange new forms – now taxonomised and given Latin binomial names – existing on the frontiers of the West’s understanding into an ordered familiarity.

The art historian Gill Saunders argues that naming and description was a process of “placing these unfamiliar plants in the existing scheme of things”.22 Assimilated into an ever-expanding universal regime of classifying life, modern science alienated these plants and animals from the original cultural contexts in which they were embedded, and through which Europeans first encountered them.

Complicating this, however, is the fact that modern scientific inquiry in the Malay world was not an unmediated process where Europeans simply entered and independently extracted information about local biodiversity for their own curiosity and profit. The Dumbarton Folio embodies the work of science as a cross-ethnic interface – one where European patrons employed Chinese labour to produce images, while Malay botanical knowledge supplied local nomenclature. This is not to downplay the fundamentally unbalanced relationship between the Europeans and their local assistants. Men like Wallace were privileged by their connection to the 19th century’s global centres of knowledge, with societies dedicated to botany, geology, zoology and other scientific disciplines blossoming in places like London and Paris. The colonisation of the Malay world enabled European scientists to travel freely and organise field research in a way that locals could not.

In fact, the Dumbarton Folio demonstrates how local knowledge almost always facilitated European access to new species found in the region. All of those gentlemen-naturalists, celebrated as “great men of science”, owed their findings to the labour of local guides and local experts who collected, preserved and identified specimens for them. Their vast tomes also relied heavily on drawn images, often executed by local artists.

Popular narratives about science, with their persistent focus on the trope of “discovery” by an individual genius, have conveniently erased the contributions of these faceless and nameless local individuals. In reality, scientific inquiry is cosmopolitan, and involves the participation of diverse communities. In drawing attention to this diversity, we can put together a fuller and more accurate history of science in the Malay world.

There is one final aspect that gives the Dumbarton Folio, and indeed natural history from that period, such an exquisitely human dimension. These edible fruits were probably drawn from a roadside marketplace, giving us a glimpse into what people ate here two centuries ago. Many of these are the same fruits we still recognise and are available today: from mangosteens and duku to langsat and jambu air. But they also depict a Malay world long embedded in the global circulation of people and goods: both the pineapple and cacao are native to South America, while the watermelon comes from Africa. Conjuring up rich aromas intermingling over the din of a dozen languages, the Dumbarton drawings are a symbol of the region’s dynamic cultures of consumption, enriched by hybrid interactions and international trade.

| Faris Joraimi wishes to record his thanks to Dr Trisha Craig of Yale-NUS College and Professor Sir Peter Crane of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation for making this study possible, as well as Dr Yota Batsaki and Dr Anatole Tchikine for their hospitality throughout his stay at Dumbarton Oaks in 2019. To access the Dumbarton Folio, visit https://www.doaks.org/resources/rare-books/album-of-chinese-watercolors-of-asian-fruits |

Faris Joraimi is a student at Yale-NUS College and will graduate in 2021. He studies the history of the Malay world, and has written for Mynah, Budi Kritik, S/pores and New Naratif. Faris was also co-editor of Raffles Renounced: Towards a Merdeka History (2021), a volume of essays on decolonial history in Singapore.

Faris Joraimi is a student at Yale-NUS College and will graduate in 2021. He studies the history of the Malay world, and has written for Mynah, Budi Kritik, S/pores and New Naratif. Faris was also co-editor of Raffles Renounced: Towards a Merdeka History (2021), a volume of essays on decolonial history in Singapore.

NOTES

-

Farquhar, W. (2015). Natural history drawings: The complete Wiliam Farquhar Collection: Malay Peninsula, 1803–1818. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 508.0222 FAR-[JSB]) ↩

-

Saunders, G. (1995). Picturing plants: An analytical history of botanical illustration (p. 15). Berkeley: University of California Berkeley Press. (Call no.: RART 743.7 SAU) ↩

-

Bleichmar, D. (2006). Painting as exploration: Visualising nature in eighteenth-century colonial science. Colonial Latin American Review 15 (1), 81–94, p. 90. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online. ↩

-

Bleichmar, 2006, p. 90. ↩

-

Together with Stamford Raffles, the Danish surgeon and naturalist Nathaniel Wallich founded the first botanical garden on Government Hill (now Fort Canning Hill) in Singapore in 1822. Wallich was previously Superintendent of the Royal Gardens in Calcutta, India. ↩

-

Archer, M. (1962). Natural history drawings in the India Office Library (p. 100). London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. (Call no.: RART 743.6 ARC) ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir, Munshi & Hill, A.H. (1985). The hikayat Abdullah: The autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.51032 ABD) ↩

-

Sweeney, S., & Phillips, N. (1975).The voyages of Mohamed Ibrahim Munshi (p. xxii). New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 MUH) ↩

-

British Library Board. (1807–1809). NHD 42. Archives and Manuscripts, The British Library. Retrieved from The British Library website. ↩

-

Marsden, W. (1783). The history of Sumatra. London: Printed for the author. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.81 MAR-[JSB]; Accession no.: B03013526I) ↩

-

Raffles, T.S. (1817). The history of Java (2 vols.). London: Printed for Black, Parbury, and Allen, booksellers to the Hon. East-India Company, Leadenhall Street, and John Murray, Albemarle Street. (Call no.: RRARE 959.82 RAF-[JSB]; Accession nos.: B29029409B [Vol. I], B29029410E [Vol. II]) ↩

-

British Library Board, 1807–1809. ↩

-

Nieuhof, J. (1703). Voyages and travels, into Brasil, and the East Indies. London: A. and J. Churchill. Retrieved from Cornell University Library Southeast Asia Visions website. [Note: NLB has the 1744 edition. See Nieuhof, J. (1744). Voyages and travels, into Brasil, and the East Indies. London: A. and J. Churchill. (Call no.: RRARE 910.41 NIE-[JSB]; Accession no.: B29265189I)] ↩

-

Rumphius, G.E. (1741). Herbarium amboinense (6 vols.). Retrieved from Botanicus.org website. (Not available in NLB holdings). For a commentary, see Hamilton, F. (1824). Commentary on the Herbarium Amboinense. [Edinburgh]: [Wernerian Natural History Society]. (Call no.: RCLOS 581.95985 HAM) ↩

-

Personal communication with Associate Professor Farish Noor, 15 August 2019. ↩

-

Sardar, M. (2004, October). Company painting in nineteenth-century India. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website. ↩

-

Noltie, H.J. (2009). Raffles’ ark redrawn: Natural history drawings from the collection of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (p. 12). Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Gardens. (Call no.: RSING 508.0222 NOL) ↩

-

Pioneered by artists Cheong Soo Pieng, Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi and Georgette Chen in the 1950s, the Nanyang Style integrates Chinese painting traditions with Western techniques from the School of Paris, and typically depict local or Southeast Asian subject matter. ↩

-

For more information about these Nanyang artists, see Tan, B., & Creamer, R. (2016). Liu Kang; Ho, S. (2015, January 28). Chen Wen Hsi; Creamer, R. (2018, January 24). Georgette Chen. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩