Man vs Nature: Speculative Fiction and the Environment

Jacqueline Lee surveys the landscape of Singapore speculative fiction to see how writers address pressing environmental concerns in their novels and short stories.

The multiple awards won by The Gatekeeper shows that speculative fiction has become a mainstream genre in Singapore. Shown here is an illustration of Ria, the medusa from the novel drawn by the author Nuraliah Norasid. Image reproduced from Nuraliah Norasid. (2015). Ria, a Novel and an Exegesis (p. 334) [PhD dissertation]. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 808.3 NUR).

The multiple awards won by The Gatekeeper shows that speculative fiction has become a mainstream genre in Singapore. Shown here is an illustration of Ria, the medusa from the novel drawn by the author Nuraliah Norasid. Image reproduced from Nuraliah Norasid. (2015). Ria, a Novel and an Exegesis (p. 334) [PhD dissertation]. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 808.3 NUR).

As the threat of climate change looms, global warming and other environmental issues are increasingly taking centre stage in popular discourse. It is also a subject that many writers of speculative fiction frequently explore in their work.

Speculative fiction is a broad category of writing that contains supernatural, fantastical or futuristic elements, and includes subgenres such as science fiction, fantasy, horror and the supernatural.1 Yeow Kai Chai, the poet and former director of the Singapore Writers Festival, notes that speculative fiction “compels us to imagine and ask questions about the fate of humanity, the environment and alternate realities”.2

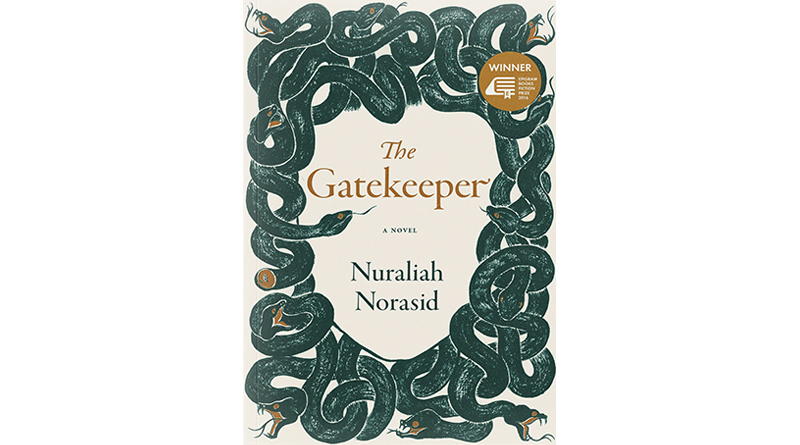

The genre has become increasingly mainstream in Singapore in recent years. In May 2017, The Straits Times reported that at least eight such home-grown novels and anthologies had been published in the previous six months.3 One such novel – Nuraliah Norasid’s The Gatekeeper4 – even clinched the Epigram Books Fiction Prize in 2016, and Best Fiction Title and Best Book Cover Design at the Singapore Book Awards in 2018.

The Gatekeeper by Nuraliah Norasid clinched the Epigram Books Fiction Prize in 2016, and Best Fiction Title and Best Book Cover Design at the Singapore Book Awards in 2018. Nuraliah Norasid. (2018). The Gatekeeper. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Ebook available from NLB OverDrive).

The Gatekeeper by Nuraliah Norasid clinched the Epigram Books Fiction Prize in 2016, and Best Fiction Title and Best Book Cover Design at the Singapore Book Awards in 2018. Nuraliah Norasid. (2018). The Gatekeeper. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Ebook available from NLB OverDrive).

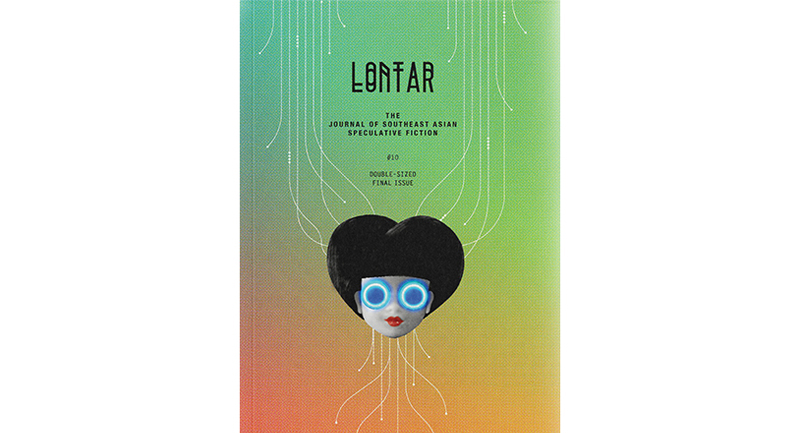

In addition to the efforts of individual writers, there have also been local platforms that promote speculative fiction. An important vehicle was LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction. Published in Singapore, the journal was active between 2013 and 2018. Its editor, Jason Erik Lundberg, has been a longtime advocate of speculative fiction in the city-state.5

LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction was published in Singapore between 2013 and 2018. Its editor, Jason Erik Lundberg, has been a long-time advocate for creating an audience for speculative fiction in Singapore. Shown here is the cover of the last issue (No. 10; 2018). Lundberg, J.E. (Ed.). (2013–2018). LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction. Singapore: Epigram Books. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF).

LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction was published in Singapore between 2013 and 2018. Its editor, Jason Erik Lundberg, has been a long-time advocate for creating an audience for speculative fiction in Singapore. Shown here is the cover of the last issue (No. 10; 2018). Lundberg, J.E. (Ed.). (2013–2018). LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction. Singapore: Epigram Books. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF).

Oil and Petrohorror

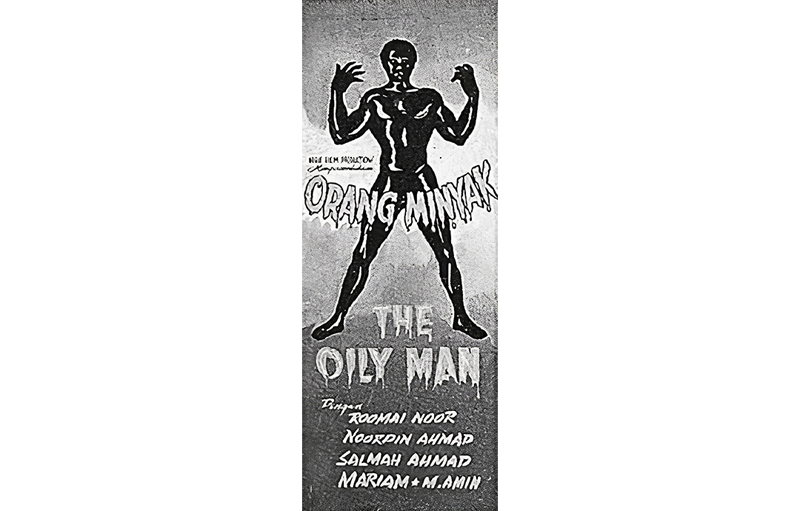

While speculative fiction that tackles environmental issues have become popular in recent times, there are some examples that go back to the immediate post-war years. In the essay “An Oily Mirror: 1950s Orang Minyak Films as Singaporean Petrohorror”, Yogesh Tulsi argues that films about the orang minyak (“oily man” in Malay) that were popular during the golden age of Malay cinema in Singapore (1950s–60s) are dramatisations of a “horrific petromodernity” and its destruction of traditional ways of life.6

The orang minyak is described as a supernatural creature coated with shiny black grease who abducts young women at night, and is able to climb walls and evade capture due to his slippery skin. While seemingly based on Malay folklore, the first mention of orang minyak in local newspapers was in Berita Harian in 1957.7

The promotional standee for Orang Minyak (The Oily Man), a Malay film directed by L. Krishnan and released in 1958. According to Malay folklore, the orang minyak is a supernatural creature coated with shiny black grease who abducts young women at night, and is able to climb walls and evade capture due to its slippery surface. Image reproduced from Millet, R. (2006). Singapore Cinema (p. 43). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL).

The promotional standee for Orang Minyak (The Oily Man), a Malay film directed by L. Krishnan and released in 1958. According to Malay folklore, the orang minyak is a supernatural creature coated with shiny black grease who abducts young women at night, and is able to climb walls and evade capture due to its slippery surface. Image reproduced from Millet, R. (2006). Singapore Cinema (p. 43). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL).

The figure was at first described to be covered in hair oil, and later coconut oil and soot, before its description coalesced into black crude oil (as portrayed in the orang minyak movies), possibly in an “unconscious attempt to represent oil’s increasing ubiquity” at the time.8 According to Tulsi, oil represents modernity and, by extension, the orang minyak represented the threat of modernity.

Loss of Biodiversity

A popular theme in general science fiction is the loss of biodiversity. One of the best known examples is Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (this novel became the basis for the cult 1982 movie Blade Runner). Likewise, large-scale extinction is also a recurring theme in Singaporean speculative fiction.

In Melissa De Silva’s short story “Blind Date” (2016), the extinction of local wildlife species parallels the extinction of Eurasians in a Singapore that relies on robots and where steel is used everywhere in place of natural materials. In this version of Singapore, the population census reports only two remaining Eurasians – 75-year-old Martin Desker and 66-year-old Gerald Pereira. Meanwhile, animals like the Sambar deer and the Raffles’ malkoha (a species of bird) are implied to be extinct, appearing as holograms programmed to pop up at intervals and accompanied by audio commentary.9 (Sambar deer have been listed as a vulnerable species on The International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species since 2008, so this scenario is not that far-fetched.10)

De Silva lightly interweaves the issues of environmental destruction and deforestation into the narrative. In the story, Martin and Gerald arrange to meet in a cafe (their “blind date”). Later, they sit in a “breathing dome” at Fort Canning and observe the “pallid sun hanging behind the veil of gases”.

At the cafe, Martin reacts against all this technology, noting it was all “very impressive, but he often felt humanity had become obscured by these wonderful technological doodahs. Even the two coffees he’d ordered over the past hour had come with sugar molecules in a steel vial. You were supposed to spray it into your drink and escape with zero calories. He’d had to ask for real sugar. Nonsense. Metal. What on earth was wrong with glass? Or wood? Surely anyone would prefer beautiful grain that told the life story of a tree? But of course, anything made from natural timber these days would cost the earth.”11

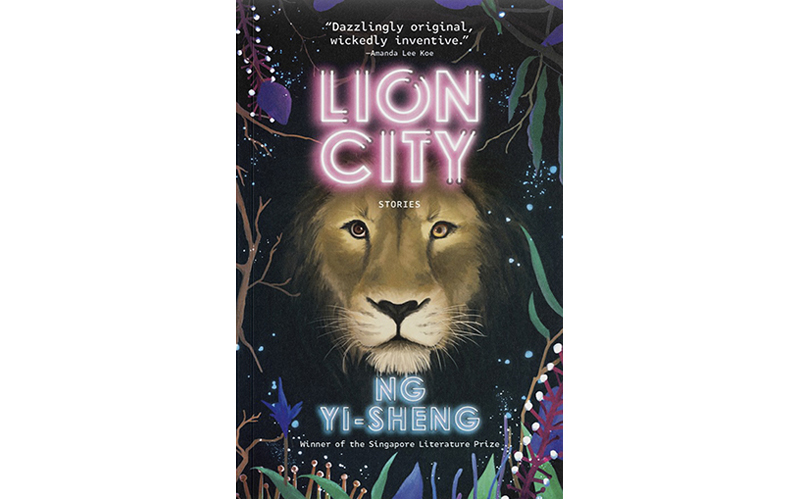

Ng Yi-Sheng’s Lion City (2019) also deals with a time where many animals have become extinct. In its titular short story, the narrator is given a behind-the-scenes look at the “animals” in the Singapore Zoo. It is revealed that the insides of these animals are made up of “wire mesh, cable spaghetti and the like, silicon garbage, the city’s detritus”.12 They wear synthetic skins and are programmed to look and act like real animals. The narrator interacts with a simulacrum of a lion cub, remarking on its similarity to a “genuine little Simba, whiskers and all”. In this alternate universe, the Singapore Zoo – and along with other zoos around the world – has been fooling unsuspecting visitors for decades by using robotic animals. It also reveals that the giant panda has been extinct for a century.

Lion City by Ng Yi-Sheng is an anthology of short stories. In the titular short story, the narrator is given a behind-the-scenes look at the “animals” in the Singapore Zoo, which are actually robots. Ng, Y.-S. (2019). Lion City. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Ebook available from NLB OverDrive).

Lion City by Ng Yi-Sheng is an anthology of short stories. In the titular short story, the narrator is given a behind-the-scenes look at the “animals” in the Singapore Zoo, which are actually robots. Ng, Y.-S. (2019). Lion City. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Ebook available from NLB OverDrive).

Land Scarcity

Land scarcity is a recurring theme among Singaporean writers. In Clara Chow’s 2017 short story “Welcome, 265 Aggregate Scorers”, the shortage of land in Singapore has pushed the country to reclaim land aggressively, to the point where the narrator notes how land reclamation projects have “gone crazy”. In fact, the country has reclaimed so much land that there is no actual sea left between the country and its neighbours. Instead, giant screens projecting the seascape have been installed. With the country “nudg[ing] up against its neighbours apologetically”, Singapore has to erect screens so that “we could keep our modesty while resisting the urge to peer into other nations’ messy bedrooms”.13

Constraints arising from the scarcity of land also provide the background for Hassan Hasaa’ree Ali’s 2013 Malay short story “Doa.com”, which presents an imaginative solution to address the paucity of land for burying the dead. In the story, technology has advanced to such a stage that it was possible to build an underground graveyard complex for the remains of the dead. Family and friends cannot visit the graves in person, but they can go online to Doa.com and select a prayer that will be played through a speaker to the underground grave. The cost of each prayer depends on how potent the prayer is claimed to be.14

Hassan Hasaa’ree Ali’s Malay short story “Doa.com” in Selamat Malam, Caesar presents an imaginative solution to address the scarcity of land for burials in Singapore. The book was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize for Malay Fiction in 2014. Hassan Hassaa’ree Ali. (2013). Selamat Malam, Caesar. Singapura: Akademi Anuar Othman. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.283 HAS).

Hassan Hasaa’ree Ali’s Malay short story “Doa.com” in Selamat Malam, Caesar presents an imaginative solution to address the scarcity of land for burials in Singapore. The book was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize for Malay Fiction in 2014. Hassan Hassaa’ree Ali. (2013). Selamat Malam, Caesar. Singapura: Akademi Anuar Othman. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.283 HAS).

Land scarcity (and alternative energy) is the theme of the 2012 short story “Chapter 28: Energy” by The Centipede Collective comprising writers Olivia Lee and Brandon Chew. In the story, the government made cremation compulsory for all newly deceased because of land scarcity. Then a law is passed to exhume all cemeteries to free up even more land for industrial, residential and commercial use. By 2040, as all columbaria have reached full capacities, Singaporeans are encouraged to scatter ashes in the waters around the island.15

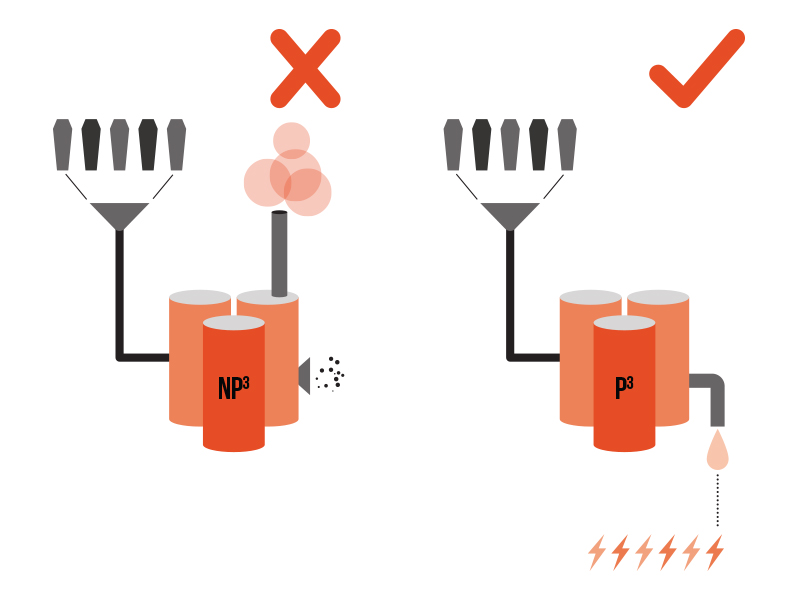

Illustrations from the short story “Chapter 28: Energy” showing the process of converting latent energy from dead bodies to produce a liquid called NecrOil that can create batteries and power cars. Images reproduced from The Centipede Collective. (2012). Chapter 28: Energy (pp. 321, 329). In J.E. Lundberg (Ed.), Fish Eats Lion: New Singaporean Speculative Fiction. Singapore: Math Paper Press. (Call no.: RSING S823 FIS)

Illustrations from the short story “Chapter 28: Energy” showing the process of converting latent energy from dead bodies to produce a liquid called NecrOil that can create batteries and power cars. Images reproduced from The Centipede Collective. (2012). Chapter 28: Energy (pp. 321, 329). In J.E. Lundberg (Ed.), Fish Eats Lion: New Singaporean Speculative Fiction. Singapore: Math Paper Press. (Call no.: RSING S823 FIS)

While witnessing his father’s cremation, one ingenious researcher in Singapore comes up with an alternative energy source inspired by cremations. Harvesting the latent energy found in dead bodies to make a liquid called NecrOil that can create batteries and power cars, Singapore becomes a “model for energy regeneration”, studied by scientists and researchers all over the world. An added bonus of this new technology is that Singapore no longer has any dead bodies to dispose of as these are automatically converted into NecrOil. “Chapter 28: Energy” is a satire on Singapore’s often quoted “only natural resource” – its people – to literally power the next generation.16

Rising Sea Levels

An oft-cited consequence of climate change is the rise in sea levels which threatens low-lying coastal areas. In percent of landmass lies less than five metres above sea level. The Centre for Climate Research Singapore projects that the country could experience “more intense and frequent heavy rainfall events, and [a] mean sea level rise of up to 1 metre by 2100”.17 Thus, the possibility that large parts of Singapore could end up being submerged by water is a very real one.

In Wayne Rée’s 2018 short story “Satay”, Singaporeans have been forced by rising sea levels to take refuge in the country’s skyscrapers. In the story, Rafi and his father, a satay seller, live in what is implied to be a repurposed Marina Bay Sands. The hotel becomes a literal stratification of the hierarchy of Singaporean society: the privileged upper classes live on the top floors of the 56-storey building, enjoy parties by the infinity pool and are referred to as “upper-level families”. The poorer people live on the lower floors, though not too low because 31 floors of the building are submerged in the sea.

Rafi and his father live on the 40th floor and are considered middle class. Rafi’s father’s satay is very popular and this helps earn them friends across all levels, and crucially, some special privileges and patronage from the upper-level residents as they are hired to grill satay for parties on the rooftop.

In one scene, Rafi stands on the rooftop – his father has been hired to provide satay for the upper-level residents – and observes how “the evening light played off the tops of the other mostly submerged skyscrapers, the waves lapping gently against the sides of what was left of the buildings”.18

While “Satay” explicitly portrays a flooded Singapore, rising sea levels are implied in Patricia Karunungan’s 2018 short story “Agatha”. The protagonist, Agatha, and other characters in the story live in a high-tech indoor facility and the only glimpse of the outside world shows “an expanse of barren land with buildings rising distantly through the haze”.

Most of the narrative takes place in this indoor facility, and the story ends abruptly with characters forced to make difficult decisions. As the flooding worsens over time, a crisis point is reached and the Singapore government decrees that all convicted and suspected criminals will be executed, and that all life support in hospitals will go offline.

The government also announces that it will deploy a dome, with the implication being that this dome is a last resort, as a way to somehow protect at least some residents of Singapore against the impending “siege of the sea”.19

A Dystopian Future

What these works demonstrate is that Singaporean speculative fiction is a rich resource for studying the environmental crises of this century. Over the last decade, writers here have been engaging with the threat of climate change by exploring possible futures. They have been looking at existing trends – global warming, rising sea levels, mass extinction of animals – and extrapolating them into the future to draw a dire picture of what Singapore, and the world, could look like.

Through their prose, the writers ask the all-important question – “What if?” What if sea levels rise and low-lying parts of Singapore become submerged? What if most flora and fauna on earth have been wiped out? What if Singapore runs out of land? Having raised these issues, perhaps the next question to ask is – “What now?”

Jacqueline Lee is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include developing and promoting the Legal Deposit and Web Archive Singapore collections.

Jacqueline Lee is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include developing and promoting the Legal Deposit and Web Archive Singapore collections.

NOTES

-

Dictionary.com, LLC. (n.d.). Speculative fiction. Retrieved from Dictionary.com, LLC website. ↩

-

Ho, O. (2017, May 2). Tall tales of Singapore take off. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 2 May 2017, p. 1. ↩

-

Nuraliah Norasid. (2018). The gatekeeper. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Ebook available from NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Lundberg, J.E. (Ed.). (2013–2018). LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF) ↩

-

Tulsi, Y. (2020). An oily mirror: 1950s orang minyak films as Singaporean petrohorror (pp. 338–385). In M. Schneider-Mayerson (Ed), Eating chilli crab in the Anthropocene: Environmental perspectives on life in Singapore. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 304.2095957 EAT) ↩

-

Wanita2 pindah takut orang minyak. (1957, October 12). Berita Harian, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

De Silva, M. (2016). Blind date. In J.E. Lundberg (Ed.), LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction, (7), 39–51. (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF) ↩

-

Established in 1964, The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List of Threatened Species has become the world’s most comprehensive information source on the global extinction risk status of animal, fungus and plant species, and is a critical indicator of the health of the world’s biodiversity. ↩

-

Ng, Y.-S. (2019). Lion city (pp. 16–33). Singapore: Epigram Books. (Ebook available from NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Chow, C. (2017). Welcome, 265 aggregate scorers. In J.E. Lundberg (Ed.), LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction, (8), 79–95. (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF) ↩

-

Hassan Hassaa’ree Ali. (2013). Doa.com (pp. 10–15). In Selamat malam, Caesar. Singapura: Akademi Anuar Othman. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.283 HAS) ↩

-

The Centipede Collective. (2012). Chapter 28: Energy. In J.E. Lundberg (Ed.), Fish eats lion: New Singaporean speculative fiction. Singapore: Math Paper Press. (Call no.: RSING S823 FIS) ↩

-

The Centipede Collective, 2012, pp. 321–324. ↩

-

National Climate Change Secretariat. (2020, December 30). Impact of climate change and adaptation measures. Retrieved from National Climate Change Secretariat website. ↩

-

Rée, W. (2018). Satay. In J.E. Lundberg. (Ed.), LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction, (10), pp. 79–92. (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF) ↩

-

Karunungan, P. (2018). Agatha. In J.E. Lundberg (Ed.), LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction, (10), 187–204. (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF) ↩