Making the Invisible Visible: Restoring the Statues of St Joseph’s Church on Victoria Street

Alvin Tan documents the painstaking process behind the restoration of the statues in St Joseph’s Church.

The spires, domes and sweeping roofs of houses of worship are at once expressions of faith and calls to encounter the divine. The dome of St Joseph’s Church, which tops a 20-metre-high octagonal belfry, makes that overture from its location along busy Victoria Street.

While the church’s architectural features are eye-catching at street level, much of the building remains hidden and invisible behind its walls. Inside, its treasures are revealed in their glory. Among these gems are the statues of saints and other figures that are strategically placed around the church for worshippers to encounter various manifestations of the divine.

As with many Catholic churches, St Joseph’s has its fair share of statues. But St Joseph’s probably has more statues than most churches here, given that its history dates back to 1853 when it was built by the Portuguese Mission. Known as São José (“St Joseph” in Portuguese), that Gothic-style building was demolished in 1906 and subsequently replaced with the current, larger building by noted architectural firm Swan & Maclaren in 1912. Over the last 150 years or so, the church – which was gazetted as a national monument in 2005 – has accumulated a number of statues that have come to be beloved by worshippers.

The 30 or so statues in the church are physical connections to the history of the church and the Portuguese Mission in Singapore. These statues are also reminders of festivals, feast days and other activities that constitute the life of a church. So when the church authorities decided that a major restoration project for the building was needed to save it, they were determined that the statues be conserved as well.

Restoring St Joseph’s

The restoration of the church initially started out as a paint job. But in June 2017, workers discovered intricate plasterwork hidden under decades of paintwork, exposing floral and foliage motifs.1 The discovery triggered a larger investigation into what else needed to be done, and a professional structural engineer was engaged to assess the building’s structural integrity.

The final report confirmed what had long been suspected: a major overhaul was needed. The building’s facade facing Victoria Street was tilted forward. Over time, this had caused cracks to ripple through the building’s 45-centimetre-thick walls. Some of these cracks stretched from the ground to the ceiling, while others were large enough to peer through. Further technical tests revealed that the building foundation had to be stabilised.

A decision was made to close the church in 2018 so that the structural issues could be rectified and the building restored. The entire restoration project was estimated to cost $24.4 million.2

Given that the church building would be undergoing a major restoration, it also made sense to look at what else needed to be repaired. As a result, church’s building committee began examining the possibility of restoring its 32 statues as well.

The statues are relatively young, dating from the early 20th century, and were mass-produced in plaster. Of the 32 statues, 14 were manufactured and distributed worldwide by Maison Raffl (also known as La Statue Religieuse), a well-known French manufacturer of religious statues. Little is known about where the other statues were manufactured. Some of these statues were bought by the church, while others were donated by individuals, or societies and associations affiliated to the church.

There were a number of options for dealing with these statues. One of the companies that the church approached said that the best (and only) approach was to strip the statues of all paintwork, including the original layer, and then repair and repaint them. This proposal was rejected because such a drastic process would result in the statues losing their material past(s) and become “new”.

To Monsignor Philip Heng, SJ,3 then the church rector, the statues had “a special historical value that connects them” to the church community. So while these were not expensive works of art, he felt it was important to conserve the statues.4

After the Straits Times ran an article in July 2017 about the church’s discovery of treasures hidden under paint,5 Filipa Machado, a Portuguese art restorer residing in Singapore, approached the church at the urging of friends to offer her services.

Trained in Lisbon and graduating top of her class in 1999, Machado had garnered about 17 years of experience working on restoration projects in Portugal. From 2009 to 2014, she was part of an award-winning restoration team that won the Prémio Vilalva award recognising excellence in the conservation of Portuguese cultural heritage at the Sacramento Church in Lisbon. In 2015, she clinched an award from the Portuguese Association of Museology for her work in restoring a 48-square-metre heritage mural painted in 1955 by the Portuguese artist Luis Dourdil.6

After reviewing Machado’s portfolio, the church building committee got her to undertake a small restoration work in order to assess her technical competence and skill. In the meantime, the committee also ran her credentials by the National Heritage Board. She passed the restoration test with flying colours and was given the task of restoring all the statues.

For Machado, the project was particularly meaningful and a source of pride as she would be “involved in the [restoration]project of a Portuguese Church [established in 1853] so far away from Portugal”.7

She was under no illusion that it would be an easy task. For a project of this size, a team is usually involved in the restoration, according to Machado. However, in this case, she was going solo.

The restoration project began in August 2018 and an air-conditioned workshop was built on the church grounds to ensure optimal storage conditions and minimise the need to transport the statues. Between 2018 and 2021, a total of 29 statues were restored. (Three statues were deemed beyond restoration and decommissioned.)

Making the Invisible Visible

At the start of the project, Machado did a comprehensive survey of the statues and put together a report for the building committee. In her initial assessment, she examined 24 statues to ascertain their physical condition. The report was mixed: 14 statues were in good physical condition, but had yellowed over time. Overpainting and haphazard repairs had also caused a further loss of detail and definition and some statues had missing fingers. Also missing were the objects representing the saints’ particular attributes or virtues.

The remaining statues were in poor physical condition: there were visible cracks, and the original paintwork was damaged and, in some instances, totally stripped off. A few statues were beyond restoration and repair.

Machado’s recommendation was to remove the overpaint, reconstruct the missing parts and restore the original paintwork.

Her approach was guided mainly by conservation principles. Every intervention had to be reversible, using techniques and materials that would only affect the statue minimally. Only durable, high-quality conservation-grade materials that were non-toxic and non-acidic could be used. Such materials would protect the work from future oxidation, water damage and exposure to light.

In addition to the technical aspects, Machado also had to ensure that the restoration faithfully represented the historical and cultural contexts of both the statue and the saint. Her sensitive approach is an indication of how the restoration of a material object can sit at the intersection of history, art, chemistry, material science and more.

St Francis Xavier

Machado’s first restoration piece was the statue of St Francis Xavier (1506–52), a task that took two weeks to complete. One of the seven original members of the Society of Jesus (also known as Jesuits), St Francis Xavier is remembered for his missionary work in establishing Christianity in Asia, the Malay Archipelago and Japan. Based in Melaka for several months in 1545, St Francis Xavier was informed that he had been appointed provincial of the “Indies and the countries beyond” while he was in Singapore at the end of 1551.8

The 150-centimetre-tall plaster statue of the saint was in poor material condition. It was dirty and its surface was marred by cracks, abrasions, holes and other lacunae. Missing fingers had been replaced with crudely shaped plaster substitutes. Although coats of paint had been applied over the decades, mostly based on the painters’ imagination and preference, these had little regard for the original colour, hue, tone and shade.

Fine details were also painted over, causing the statue to lose definition. It had a mildly jaundiced skin tone and its facial expression was flat and lacked affect. A dark-purple stole (a band of cloth used as a liturgical vestment by ordained ministers) only made the statue look gloomy and dirty. In short, St Francis Xavier had aged a lot and rather ungracefully.

The first step in the restoration work involved cleaning off the surface dirt and determining the number of layers of overpaint. Small areas were examined by using a stainless steel surgical scalpel to scrape away thin layers of overpaint.

After exposing the original paintwork, a suitable solvent was applied with a brush to dissolve and remove the overpaint. Ethanol, which is colourless and evaporates quickly and cleanly, was then used to remove any residual paint. All the old physical repairs were also removed. Lumps of plaster, glue and even the odd nail were carefully taken out with a precision power drill. A solvent was also used to dissolve visible rust.

Having revealed the original paintwork and stabilised the statue’s structural integrity, physical repairs began. Two replacement thumbs and one replacement finger were fabricated from plaster and then attached to the statue with conservation-grade glue. Conservation-grade filler – more durable, has stronger adhesive qualities and is less toxic – was used to fill in small holes, replace missing plaster and smooth over abrasions.

To protect the original paintwork from oxidation, scratches, water damage and dirt, the statue was then varnished and a layer of water-resistant acrylic resin applied.

Next, pigment was used to restore St Francis Xavier’s surplice – a tunic with large sleeves, usually knee length, worn by the clergy – to its original porcelain white, with particular attention given to the detailing and patterning at its hem. The dark-purple stole was restored to its original hue of lustrous, rich gold using a gilding liquid made from mixing real gold leaf with varnish.

With its now soulful eyes, kindly visage and handsome vestments, the restored statue of St Francis Xavier will once again grace the church building.

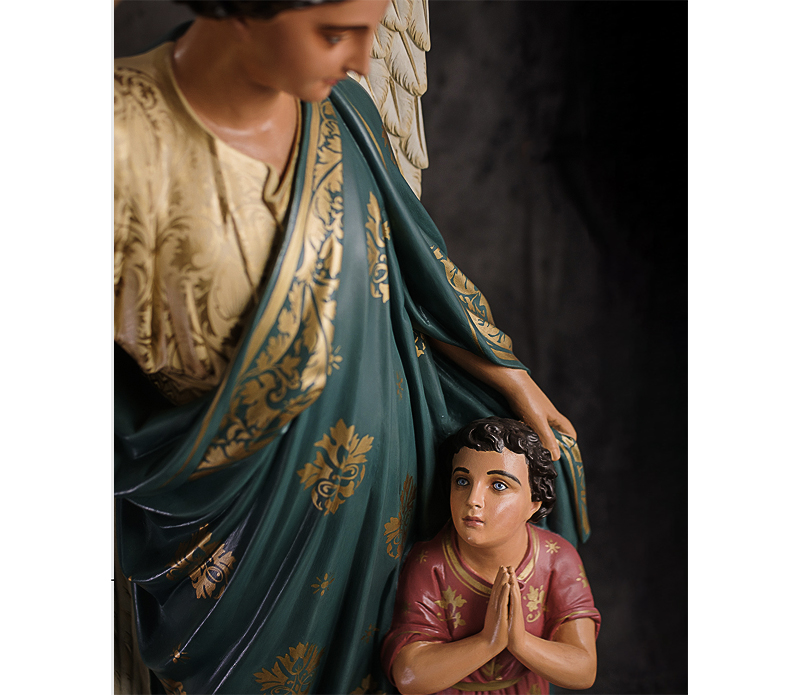

Guardian Angel and Child

Angels feature prominently in the Bible and Catholics traditionally believe that there are guardian angels who watch over, guide, protect and accompany the faithful throughout their lives.

In St Joseph’s, the statue of a guardian angel sits in a niche situated after the portico, welcoming worshippers just as they enter the church. The guardian angel, with a child under its protective mantle and the shadow of its wings, looks on the child and points his finger heavenward.

Unfortunately, years of overpainting had hardened the facial expressions of the angel and child. The angel wore a nonchalant fixed stare while the child responded with a look of doubt. The friendly relationship of trust and protection, so pronounced in the original statue, had been lost. Further work uncovered details on the angel’s wings and mantle. With the dirt and overpaint stripped away, the soft and gentle aspects of the facial expressions of the statue were revealed. Using the same process as she did in the restoration of the statue of St Francis Xavier, Machado reinstated the detailed finery that clothed both the angel and child.

St Sebastian

The biggest technical challenge in the entire project was the restoration of the plaster statue of St Sebastian, the patron saint of archers, athletes and soldiers. Martyred in third-century Rome during the Roman emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians, St Sebastian is usually depicted as a handsome, fair-skinned youth pierced by arrows. The difficulty in restoring this statue was not because much of the original paintwork had been lost. In fact, it was the opposite.

When evaluating the statue, Machado “was surprised by the pristine condition of the original chromatic layer” because “when an artwork is so heavily repainted, it is because the original condition is bad”.

To preserve the original paintwork, she chose therefore to remove the overpaint by hand rather than risk damaging it by using a chemical solvent. Because she had to “remove all the overpaint with a scalpel very slowly and carefully”, Machado said that she came to “appreciate every detail of the statue”.9 Over a fortnight, she spent consecutive 12-hour days to complete the removal process.

It was an effort that fully stretched Machado’s professional and technical skills. She had to constantly make judgement calls based on her experience, guided by visual inspections and tactile feedback when applying the scalpel. This was complicated by the knowledge that any damage to the original chromatic layer due to clumsy or hasty execution would be irreversible.

In the end though, all that effort paid off. Machado said she was “very moved by the [facial] expression of the statue” and she was pleased to be able to “bring it back to its original condition”. 10

Looking back, Machado said she was extremely proud of the work she had been able to accomplish on this project, “to have done such a big number of artworks by myself in such a short amount of time”.11

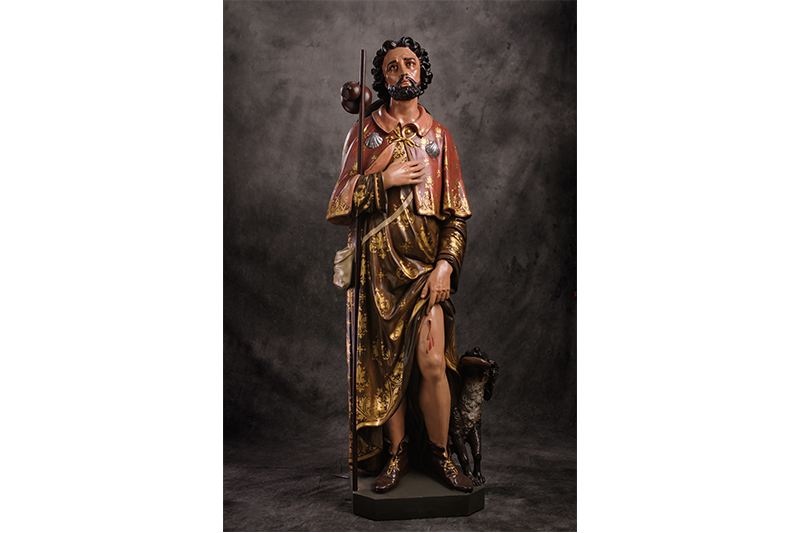

St Agnes and St Roch

Of all the statues Machado restored, her favourite is that of St Agnes of Rome, a patron saint of virgins, girls and chastity. St Agnes was merely a young girl of 12 or 13 when she was martyred during a wave of persecutions in 303 CE unleashed by the Roman emperor Diocletian. The statue depicts a young woman with long, flowing tresses, wearing a Roman tunic with a palla (long shawl) draped over it. In her left arm, she is cradling a lamb.

Unfortunately, the old paint job had given the statue a flat and lifeless appearance. After Machado removed the old paint and restored the statue to its original appearance, the lavishly patterned ivory white tunic and emerald green palla decorated with an intricate gold motif became visible. The headband was festooned with dusty-vermillion roses, which complemented the soft tones of rose pink on her cheeks.

Machado’s other favourite statue is St Roch, a male saint canonised in the 16th century. Among other things, St Roch is a patron saint of dogs, invalids, the falsely accused and bachelors. Machado “love[d] all the decorative elements of its clothing” and being an animal lover, the inclusion of a dog as part of the statue delighted her. She felt that it was “one of the most beautiful of the male [statues]” she had restored.12

The Way of Truth, Beauty and Goodness

As the restoration of St Joseph’s Church approaches completion in late 2021, after almost three years, its full architectural splendour will be made visible with its original flooring reinstated, new lighting and paintwork. The statues will once again take up their places in niches that line the nave and transept, their finery revealed by soft illumination.

Reverend Father Joe Lopez Carpio, the current rector, is pleased with the outcome of Machado’s hard work: “The statue restoration has been executed professionally alongside the building restoration. The statues no longer have any cracks or other physical damage. Their original colours have been restored, together with their facial expressions, which make them come alive. We are now working to perfect the illumination for the statues so that their restored beauty can be seen by every visitor to the church.”13 In short, to encounter the invisible that has been made visible.14

Postscript: The church was reopened on its 110th anniversary on 30 June 2022 .15

Alvin Tan is an independent researcher and writer with a strong focus on Singapore history, heritage and society. He is the author of Singapore: A Very Short History – From Temasek to Tomorrow and the editor of Singapore at Random: Magic, Myths and Milestones.

NOTES

-

Melody Zaccheus and Adrian Lim, “Treasures Hidden Under Layers of Paint,” Straits Times, 30 July 2017, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saint Joseph’s Church, Restoring Saint Joseph’s Church: Bringing Life and Colour to a National Treasure (Singapore: Saint Joseph’s Church, undated), 44. (Not available in NLB’s holdings) ↩

-

Members of the Society of Jesus – a religious order of the Catholic church headquartered in France – use the letters SJ after their personal names. This is an abbreviation of their Congregation’s name. The members of this order are called Jesuits. ↩

-

Monsignor Philip Heng, SJ, interview, 17 July 2021. ↩

-

Zaccheus and Lim, “Treasures Hidden Under Layers of Paint.” ↩

-

Luis Dourdil (1914–89) was a 20th-century Portuguese artist. A self-taught man, he created several notable wall paintings and murals. See “Luis Dourdil,” Prabook, accessed 16 July 2021, https://prabook.com/web/luis.dourdil/3742719. ↩

-

Filipa Machado, interview, 26 February 2021; Filipa Machado, email , 22 July 2021. ↩

-

“Saint Francis Xavier,” Jesuits, accessed 15 June 2021, https://www.jesuits.global/saint-blessed/saint-francis-xavier/. ↩

-

Filipa Machado, email, 22 July 2021. ↩

-

Filipa Machado, interview, 26 February 2021. ↩

-

Filipa Machado, interview, 26 February 2021. ↩

-

Filipa Machado, interview, 26 February 2021; Filipa Machado, email, 22 July 2021. ↩

-

Reverend Father Joe Lopez Carpio, email, 30 July 2021. ↩

-

St John of Damascus wrote: “For the invisible things of God since the creation of the world are made visible through images.” See “Medieval Sourcebook: John of Damascus, in Defense of Icons c. 730,” Fordham University, accessed 18 August 2021, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/johndam-icons.asp. ↩

-

Ng Keng Gene, “Restored St Joseph’s Church in Victoria Street Reopens on its 110th Anniversary,” Straits Times, 1 July 2022. ↩